Полная версия

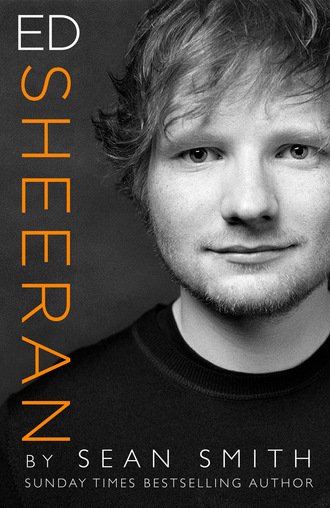

Ed Sheeran

Ed was immediately hooked. He went out and bought Damien’s debut album O the very next day, which was later his choice in Q magazine’s fascinating ‘The Album that Changed my Life’. He admired its honesty and rawness: ‘It was like he’d reached down his throat, grabbed his heart, ripped it out, stuck it on a plate and served it up to the world.’ Ed couldn’t wait to share his discovery with his friends. Unfortunately the Clifford brothers thought it was ‘shit’ so Rusty was hastily disbanded due to artistic differences. The falling-out was an early indication to Ed that he was better off doing it all himself.

Damien was born in Dublin and brought up in the thriving town of Celbridge, about fourteen miles from the city. He was already in his late twenties when he released the album that made his name internationally. He had spent his first years in music as part of a rock group called Juniper, which he had formed with friends from secondary school. Eventually, he became disenchanted with the musical compromises he felt he was making to please their record company. He became his own man and travelled around Europe busking, eventually settling in Tuscany where he wrote many of the songs for O.

His first solo composition to be released as a single was the agonisingly beautiful ‘The Blower’s Daughter’, which highlighted his ability to share his emotions with the listener. Ed was entranced by Damien’s ability to sing with such passion and share his private and innermost feelings with the world. Some of the songs were inspired by his relationship with the singer Lisa Hannigan, who provided fragile, haunting vocals alongside Damien on many of the tracks. She was his muse, they worked well together and he loved her taste.

Commercially, Damien has yet to top O. The Irish Independent described the album as ‘one of the great Irish cultural success stories of the decade’. Sadly, Damien and Lisa would later split acrimoniously. The notoriously private singer heartbreakingly told the Irish music site Hot Press, ‘I would give away all the music success, all the songs and the whole experience to still have Lisa in my life.’

Ed had soon learned to play all these poignant songs but he had to wait to see Damien in concert for the first time. That changed in 2004, during the late summer holidays in Ireland. Ed’s cousin Laura told him that Damien was playing a low-key gig for under-eighteens at Whelan’s in Dublin where she lived. The pub in Wexford Street was widely recognised as the original music venue in the city and was internationally famous for the quality of the acts that had performed there and as a popular location for television and films.

Laura and Ed were able to get tickets that stipulated, ‘All adults must be accompanied by an under-18’. The adult, as ever, was John Sheeran. The gig would prove to be highly significant for Ed, one of the most important evenings of his life so far. For the first time he saw a solitary singer captivate an audience by performing his own songs: ‘He holds them in the palm of his hands with just songs he has written on his own with a guitar.’ Ed stood at the front, unbothered at being surrounded mainly by winsome teenage girls.

Afterwards, John took his two charges into the front bar area where Ed, who barely looked his then age of thirteen, had his first experience of a meet-and-greet where an artist takes the trouble to chat, sign autographs and pose for pictures with members of the audience. This interaction was an essential part of the whole experience of small gigs in pubs and a lead that Ed would follow diligently in the future.

He was lucky in that he was standing next to Damien’s cellist, Vyvienne Long, who asked him, ‘Can you watch my cello for a bit?’ He dutifully guarded the instrument for twenty minutes until she reappeared, this time with Damien and the rest of the band. Ed told Lisa Hannigan he hoped to make a recording soon and she sweetly gave him an address so that he could send her a CD when it was finished. Ed, in a bright yellow T-shirt, had his picture taken with Damien, who was wearing a red hoodie, the same item of clothing that would be associated with Ed when he first started gigging. While not exactly scruffy, Damien was clearly an artist unbothered by image and the need to look like a star every minute of the day.

When he met Damien, Ed thought he was very cool: ‘If he had been a dick, I’d probably be working in a supermarket.’ He would later admit that it was life-changing – at that moment, he decided that he, too, was going to write songs like Damien. He was not a teenager who dreamed of doing something: he would go and do it. He would be a singer–songwriter, and one day he would appear at Whelan’s with just a guitar. Like Damien, he was destined to write many songs that would never see the light of day. Both were constantly creative.

Fortunately, his cousin Laura shared his enthusiasm. Whenever they got together, Ed would say, ‘I’ll be Damien, you be Lisa,’ and they would record all the songs on O, which Ed knew backwards and forwards, in the garden shed at her family’s house in Tuam, County Galway. Ed was lucky to have two older cousins, Jethro and Laura, who were inspired by the music he loved.

Back in Framlingham for his next lesson with Keith, he couldn’t wait to tell his guitar mentor that he had seen Damien Rice and he, too, was going to be a singer–songwriter. First, though, he needed to find an old guitar. Damien played one from the Lowden guitar factory in Ireland, which looked the worse for wear but had a beautiful sound that filled the room. Keith recalls, ‘I turned up one day as usual and he said to me straight away, “Have you got an old acoustic guitar? I don’t want a new one. I want an old, battered, characterful acoustic guitar.” So I told him I did have one actually, a Dallas model I’d bought for my wife Sally twenty-five years or so before. We didn’t use it much anymore so I sold it to him. He wanted to play “Cannonball”. And he started generally to get more into acoustic music.’ Ed was thrilled to have the instrument as it meant he could practise playing Damien’s music and make it sound more authentic. He probably knew the songs better than anyone other than the artist himself. That was part of his extraordinary gift. He was a sponge who could soak up a piece of music, then improvise and experiment to turn it into something entirely new and unique to him.

An additional attraction of O was that each song seemed to build slowly from an initial guitar riff and blossom into an emotional climax – something Ed aspired to achieve with his songs from the beginning.

For Christmas 2004, Ed’s main present was a Boss Digital Recording Studio, a home studio for his bedroom. He immediately threw himself into recording his first album. He was determined to finish it in the holidays so it would be ready in time for the next term at Thomas Mills. He started work on Boxing Day 2004, and had completed fourteen songs twenty-four days later on 19 January 2005. Although he was proud and excited at the time, he now keeps Spinning Man away from the public. It is an amazing achievement for a thirteen-year-old, but it sounds nothing like the Ed Sheeran songs we know today.

For starters it’s a rock album, bearing far more of the influence of Green Day, Guns N’ Roses and Oasis than the acoustic lyricism of Damien Rice. He seems to have taken the power punk of Green Day’s ‘American Idiot’, combined it with the more traditional rock of ‘Sweet Child of Mine’, and thrown in a dash of ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’.

He had been building up his collection of guitars and wanted to play his best one on the album. He had acquired a striking B. C. Rich rock guitar during his Rusty days. Slash and Axl Rose played B. C. Rich models onstage. You couldn’t miss Ed’s, which was purple with gold hardware. Keith was impressed: ‘It was a really serious guitar with a beautiful bird’s-eye maple neck.’

Spinning Man featured fourteen tracks and fifty minutes of music. The album starts with a drum intro and a dirty guitar riff. This is ‘Typical Average’, one of the first songs Ed wrote. Lyrically, it’s not a high point, repeating, ‘I’m a typically average teen, if you know what I mean’, but it does possess a strangely catchy quality, even if the vocal is distinctly shaky.

The second track, ‘Misery’, contains another powerful rock solo, setting the tone for the guitar work on the complete album. His first rap is ‘On My Mind’, which seems to be directed at an unnamed girlfriend and, while it lacks the power of his later, more sophisticated work, it sounds more like Ed than his Green Day numbers. And it was the first Ed Sheeran composition to contain the phrase ‘fuck off’.

Even more interesting is ‘No More War’, which is a protest song about the futility of war. The older Ed would deliberately avoid writing strong political statements so this is a rare song that proclaims, ‘Put down your guns because it’s not for fun’. ‘Moody Ballad of Ed’ is back in ‘Typical Average’ territory and is probably even shakier vocally as he drifts in and out of tune. He sounds a little better on a slower number, ‘Addicted’, but ‘Butterfly’ and ‘Concord’ are more representative of what is basically a rock album. The last consists of crashing chords and a power solo that would have done Deep Purple or Jeff Beck proud circa 1970. There’s more of that on ‘Crazy’, which has an even longer head-banging guitar solo, and ‘Broken’, which seems to reference ‘Sunshine of Your Love’, a classic Cream track that featured Eric Clapton.

That rock sound continued on ‘Celebrity’ and ‘Sleep’, which must have been a precious commodity in the Sheeran household, with Ed on electric guitar in one room and Matthew on violin in another. ‘Mindless’ was a post-punk homage to Kentucky Fried Chicken before the album ended on a high note with ‘I Love You’, which was probably the closest track to future Ed Sheeran. The problem with his slower songs was that they exposed more obviously his vocal limitations at the time. As every musician knows, recording the album is only the start of the process. He needed a title and decided to call it Spinning Man after a late work by the great surrealist Salvador Dalí. John Sheeran had hung a print on a wall at the house so Ed was very familiar with it and the title seemed perfect for a spinning CD.

To add to the professional feel of the project, Ed enlisted his parents to help produce a proper CD, complete with case and sleeve notes, which proudly declared that all the material was copyright Ed Sheeran and Sheeran Lock Ltd. He asked Alison Newell, a local artist and family friend, to design the cover. She featured his Faith guitar to one side of a black background. Some delicate white spirals, shaped like a prawn, make simple embroidery. The back featured a photograph taken by his father of Ed playing the same guitar on the streets of Galway the previous summer, his first venture into busking. In his thanks, Ed included ‘all those who put money into my guitar case’.

He also thanked his cousins Laura and Jethro, his brother Matthew and all Sheerans and all Locks. There are thanks, too, for Mums and Dabs, his pet names for his mother and father since he was a toddler. Among the friends he acknowledges, he mentions Claire – the inspiration for some of the songs, including ‘I Love You’. According to Ed, they had a very innocent hand-holding friendship that was over by the time he recorded the album, although he was upset when they broke up.

For his musical inspiration, Ed cites Damien Rice, Eric Clapton and ‘Jimmy H’ (presumably Jimi Hendrix) but there is sketchy evidence of their influence on the album. There’s something of Hendrix and Clapton but Spinning Man bears no resemblance to Damien Rice, who really doesn’t do solos, big riffs or long instrumentals on an electric guitar. At thirteen, Ed was still searching for his own sound and his first album was really a hangover from his schoolboy band Rusty. He is, though, too modest about the achievement.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Spinning Man is its maturity, best exemplified by his personal message on the sleeve notes: ‘Songwriting and playing the guitar are like having a direct line to my thoughts and feelings. Everyone has strong feelings whatever their age. We can all feel love, joy, longing, pain and hate.’ His mother may have used her editing skills to help but it clearly reveals Ed’s early self-awareness.

He sent the CD to Lisa Hannigan but wished he had waited when he didn’t get a response. The reaction from those he played it to in Framlingham was very encouraging. Nobody wanted him to lose heart by being over-critical of his first recordings, particularly his mother and father. They agreed that if he wanted to make money out of his music, it had to be recorded to a higher standard than he could achieve in his bedroom. He also needed to work on his singing.

When his mum and dad realised how seriously Ed was taking his music, they asked Keith, who had been a television and radio producer, if he could find a local studio to record some of the songs to a more professional standard: ‘John said to me, “Give him some experience in a studio.”’ John was more interested in Ed spending time in a proper studio than in the finished product.

They found the ideal location just a few miles away in the town of Leiston at the renowned Summerhill School, the progressive educational facility founded by A. S. Neill. His grandson Henry Readhead ran the studio there mainly for the school but said that Ed could come with Keith for a session in March 2005.

Keith agreed to waive his fee as producer for the day in return for an hour or two in which John would show him how to improve his business online and make better connections for his own music and performance. John taught him how to build a network of links so that one gig would lead to another. Imogen told him, ‘It’s the currency of the day.’ That system of barter had served Sheeran Lock well and would continue to be useful to Ed as he sought to promote his work.

For The Orange Room, named in honour of his bedroom, they chose Ed’s five favourite tracks from Spinning Room and put them in a different order: ‘Moody Ballad of Ed’ followed by ‘Misery’, ‘Typical Average’, ‘Addicted’, finishing again with ‘I Love You’.

The most striking improvement from Spinning Man was the use of acoustic guitar and, generally, a better vocal, but his attempt at falsetto on ‘Addicted’ needed plenty of work. Occasionally, there are hints of the later Ed Sheeran. Keith remembers doing his best to convince Ed that he needed to tune his guitar all the time because it would show up on an edit even if it was just slightly out of tune: ‘He was a little bit lazy about it.’

Ed had turned fourteen and was beginning to stick up for himself musically. When Keith hinted that a vocal was just a little bit out of tune and they should go back and do it again, Ed was quite clear: ‘I like that. I want to keep that as it is.’ Henry acted as sound engineer and one of his protégées, Megumi Miyoshi, who was sixteen and a promising singer, helped with mixing and some backing vocals.

The Orange Room clearly illustrates the growing influence of Damien Rice, although ‘Typical Average’ still sounds like Green Day jamming after a heavy night out and is not remotely related to anything from O.

Ed saved up and pooled all his resources to have a thousand CDs produced, which was quite optimistic. He proudly took them to school and offered them round for a fiver. Most of them sat around in boxes at home, where they remained until he became famous. Then he had to ban his mum from selling either The Orange Room or Spinning Man.

In an interview on The Jonathan Ross Show in December 2014, Ed played a short segment of a song from his phone. It was ‘Addicted’ and sounded very average. His guitar work was good but not the vocal, which had cats running for cover. In Ed’s defence, his vocal problems were mainly because his voice had yet to break so he struggled with intonation. But as Ed accurately commented, ‘You have to learn and really practise.’

5

The Loopmeister

One evening Keith and Sally Krykant were among a group of friends invited round to John and Imogen’s house for dinner. When they arrived, Preston Reed was already sitting at the dining table. Anyone taking an interest in guitar would have known about him, a striking figure who featured often in the serious music press talking about his unique playing style.

Ed had noticed in a guitar magazine that the virtuoso player was offering places on a summer-school venture at his home in Scotland. He would be teaching his percussive method, known in the business as ‘tapping’, to a few chosen students during the summer holidays. Ed set about convincing his parents that the workshop was vital to his development as a musician.

Preston, it transpired, was playing a gig locally and the Sheerans went along. Instead of grabbing a quick autograph, they invited him to stay at the house; he accepted. Keith was particularly impressed: ‘This guy is a world-class international player, who had developed his own style of playing. It was completely different to just changing the tuning.’

Presumably John and Imogen made a deal involving the ‘currency of the day’ because, during the next summer holidays, Ed set off with his father on a train to Girvan on the Ayrshire coast for a five-day summer workshop. Preston had moved to this beautiful part of Scotland, fifty miles south of Glasgow, from his home in Minneapolis in 2001.

This was not a holiday for Ed, although he and his father managed to fit in a boat trip to Ailsa Craig, the famous granite island in the Firth of Clyde. Preston was impressed by Ed’s work ethic, unusual in one so young: ‘He was intelligent and quick; he very quickly picked up the things he had come up to learn. Even at fourteen, you could tell he had a real determination and ambition.’

The trip was made more memorable for Ed by the presence of the only other student on the trip, an amazing guitar player from Oklahoma called Jocelyn Celaya, who would develop a strong following in subsequent years as Radical Classical. Jocelyn had arrived with her boyfriend, who told everyone that he used to be a gangster in Mexico. Ed, who was enthusiastic about gangsta rap at the time, couldn’t believe he was face to face with a real one and bombarded him with questions. On the last night, everyone got together for a party and Preston played some of his own compositions including ‘Fat Boy’, ‘Metal’ and ‘Ladies Night’. Ed entertained everyone by making up rap lyrics to accompany the music. ‘He just rattled it off,’ recalled Preston. ‘It was quite funny and impressive as well.’

On his return to Framlingham, Ed was not about to become the second Preston Reed but the interlude helped him view the acoustic guitar as more than just a stringed instrument. Preston’s technical innovations showed him ‘the music you could make using the guitar as a source of sounds’. Ed absorbed that lesson from his trip to Scotland and would use it in his own way when he was introduced to an even more important character in his development as a performer.

But, first, he had to go back to school. Ed was fortunate in that it wasn’t just his mum and dad who recognised he had a special talent and could make something of his music. The director of music at Thomas Mills, Richard Hanley, realised early on that the teenager was different from his other students and needed a more thoughtful approach. Richard specialised in classical music and was more closely involved with teaching Matthew, but he followed the headmaster’s lead and gave all his students the opportunity to flourish. That was the key for Ed, who has always acknowledged the debt he owes his school.

At first, Richard was hoping to persuade Ed to follow his brother and join the school orchestra, but soon discovered he was persevering with the cello on sufferance. Ed was relieved to give it up and concentrate on the guitar. He could often be found in one of the small practice rooms in the music department working on a new song. Richard explains, ‘I think the school gave him the chance to be creative, to have the time and space to play and compose and perform.’ His passion for his music was all-consuming.

Ed was never going to match Matthew’s academic dedication. Even Imogen acknowledged that her younger son was not an exam person and struggled to apply himself to read music properly. In many ways, though, Matthew was the more eccentric of the two talented brothers. Richard acknowledges that Matthew was very creative as well as academic: ‘He had some quite avant-garde ideas.’ One Easter he composed ‘Broken Pavements’ for the school concert at St Michael’s: ‘It was a very atmospheric piece. I can still remember the sunlight pouring through the great east window at the church illuminating the players. It was a magical moment.’

As teenagers, the two Sheeran boys were totally different. They had their own groups of friends and just did their own thing. For a time, Keith Krykant taught Matthew as well: ‘He particularly wanted to know about jazz improvisations. He was very mathematical in his music and was very interested in theory. He wanted to know how the notes added up mathematically to give a certain chord.

‘He wanted to consolidate some of the things he was doing on the piano and understand how they related to the guitar. He used to compose on a computer and had a much more mechanical approach to that than Ed, who was more interested in getting a song out with a rhythm and a melody.’ In his own way, Matthew was just as ambitious as Ed: he wanted to establish himself as a classical composer. The two boys never fell out but, as Keith remembers with a smile, ‘They never used to speak to each other in the house.’

Keith was still trying to teach Ed some music theory but he was fighting a losing battle. Every week he would arrive at the house with a careful plan for the lesson with ‘Edward’ – as he always called him, just as his parents did. He explains, ‘I would decide that we would take a piece of music – pure music notation – and I would explain to him how we would get that on to a guitar. It is quite tedious. And we maybe would get five minutes into the theory and he wasn’t really interested in it. He would suddenly say, “Oh, Keith, do you want to hear a song that I wrote last night at one o’clock in the morning?” And I would say, “OK.” So he would start playing this song. And ask me, you know, “What do you think of this?” And I might suggest that he put something extra in just to bridge the chords – harmony, if you like. And if he liked it, he would light up and go, “Wow, that really works now. Keith, you’re a genius!”’

Ed was showing great maturity for his age in what he was listening to and what he wanted to play. His father’s taste had rubbed off on him. He still wanted to enjoy his favourite hip-hop artists but, post Damien Rice, he was developing more interest in singer–songwriters such as Ray LaMontagne, whose debut album, Trouble, in 2004, had showcased his distinctive vocal style, as well as all-time greats, including Paul Simon. He spent an entire lesson with Keith learning how to play the famous Simon and Garfunkel hit ‘Sound of Silence’.

‘You could see that he liked songs with strong melodies,’ observes Keith. ‘Most of the kids at the time were listening to The X Factor, which had just started, and following that, but he was appreciating other things.’

Another of Ed’s characteristics that served him well as a teenager was his lack of fear. He was appreciative but not overawed by the occasion. He took meeting Preston Reed in his stride. On another memorable occasion John and Imogen had arranged a dinner party where the guests included the local vicar. Keith and his wife were there: ‘Edward sang a ballad in the front room in front of the vicar and everybody else in a very, very confident and emotional way. It was very mature because he was only fourteen. It was extraordinary. Most of the children I teach won’t ever sing or play in front of their mum and dad. In fact they will play in front of anyone else but their mum and dad. But his mum and dad were there and he sang this song and completely held the audience – except the vicar, who can’t stand guitar music.’