Полная версия

The Hundred and One Dalmatians Modern Classic

Not many days after this, all pups began learning to lap milk for themselves and could soon eat milk puddings and bread soaked in gravy. They were now much too big to go on living in cupboards. Missis and her eight were moved down to the laundry, while Perdita’s seven had the run of the kitchen – where they got terribly under the Nannies’ feet.

‘What a pity they can’t be in the laundry with their brothers and sisters,’ said Nanny Cook, one morning.

‘Missis might hurt them – she wouldn’t know them for her own now,’ said Nanny Butler. ‘And she and Perdita would fight.’

Pongo heard this and decided something must be done. For he knew that, whatever usual dogs would do, Missis would know her own puppies and she and Perdita would not fight. So he had a word with Missis, under the laundry door, and that afternoon, when the Nannies were upstairs, he took a flying leap at the door and managed to burst it open. Out hurtled Missis and eight puppies and when the Nannies came downstairs they found Pongo, Missis and Perdita all playing happily with fifteen puppies – who were now so mixed up that it took the Nannies all their time to decide which pups had been brought up by which mother.

After that, all pups lived in the laundry. The door was kept open and a piece of wood was put across it high enough to keep all puppies in – but low enough to be jumped by Missis and Perdita when they wanted to come into the kitchen.

By now it was December but the days were fine and surprisingly warm so the puppies were able to play in the area several times a day. They were quite safe there for the gate at the top of the steps which led to the street now had a strong spring to keep it closed. One morning, when the three dogs and the fifteen puppies were taking the air, Pongo saw a tall woman looking down over the area railings.

He recognised her at once. It was Cruella de Vil.

As usual, she was wearing her absolutely simple white mink cloak, but she now had a brown mink coat under it. Her hat was made of fur, her boots were lined with fur, and she wore big fur gloves.

‘What will she wear when it’s really cold?’ thought Nanny Butler, coming out into the area.

Cruella opened the gate and walked down the steps, saying how pretty the puppies were. Lucky, always the ring-leader, came running towards her and nibbled at the fur round the tops of her boots. She picked him up and placed him against her cloak, as if he were something to be worn.

‘Such a pretty horse-shoe,’ she said, looking at the spots on his back. ‘But they all have pretty markings. Are they old enough to leave their mother yet?’

‘Very nearly,’ said Nanny Butler. ‘But they won’t have to. Mr and Mrs Dearly are going to keep them all.’ (Sometimes the Nannies wondered just how this was going to be managed.)

‘How nice!’ said Cruella, and began going up the steps still holding Lucky against her cloak. Pongo, Missis and Perdita all barked sharply and Lucky reached up and nipped Cruella’s ear. She gave a scream and dropped him. Nanny Butler was quick enough to catch him in her apron.

‘That woman!’ said Nanny Cook, who had just come out into the area. ‘She’s enough to frighten the spots off a pup. What’s the matter, Lucky?’

For Lucky had dashed into the laundry and was gulping down water. Cruella’s ear had tasted of pepper.

Every day now, the puppies grew stronger and more independent. They now fed themselves entirely, eating shredded meat as well as soaked bread and milk puddings. Missis and Perdita were quite happy to leave them now for an hour or more at a time, so the three grown-up dogs took Mrs Dearly and Nanny Butler for a good walk in the park every morning, while Nanny Cook got the lunch and kept an eye on the puppies. One morning, when she had just let them out into the area, the front door-bell rang.

It was Cruella de Vil and when she heard Mrs Dearly was out she said she would come in and wait. She asked many questions about the Dearlys and the puppies and went on talking so long that at last Nanny Cook said she really must go down and let the puppies in, as a cold wind was blowing. Cruella then said she would walk in the park and hope to meet Mrs Dearly. ‘Perhaps I can see her from here,’ she said, strolling to the window.

Nanny Cook also went to the window, intending to point out the nearest way into the park. As she did so, she noticed a small black van standing in front of the house. At that very moment, it drove off at a great pace.

Cruella suddenly seemed in a hurry. She almost ran out of the house and down the frontdoor steps.

‘Can’t think how she can move so fast, huddled in all those furs,’ thought Nanny Cook, closing the front door. ‘And those poor pups, in only their own thin little skins, catching their death of cold!’

She hurried down to the kitchen and opened the door to the area.

Not a pup was in sight.

‘They’re playing me a trick. They’re hiding,’ Nanny Cook told herself. But she knew there was nowhere for fifteen puppies to hide. All the same, she looked behind every tub of shrubs – where not even a mouse could have hidden. The gate at the top of the steps was firmly closed – and no pup could possibly have opened it. Still, she ran up to the street and searched wildly.

‘They’ve been stolen, I know they have!’ she moaned, bursting into tears. ‘They must have been in that black van I saw driving away.’

Cruella de Vil seemed to have changed her mind about going into the park. She was already halfway back to her own house, walking very fast indeed.

THROUGH HER TEARS, Nanny Cook stared towards the park. She could now see Mrs Dearly, Nanny Butler and the three dogs, who had just turned for home. It seemed a strange and terrible thing that they could be strolling along so happily, when every step brought them nearer to such dreadful news.

As they came across the Outer Circle, Nanny Cook ran to meet them – crying so much that Mrs Dearly found it hard to understand what had happened. The dogs heard the words ‘puppies’, saw Nanny Cook’s tears, and rushed down to the area. Then they went dashing over the whole house, searching, searching. Every few minutes, Missis and Perdita howled, and Pongo barked furiously.

While the dogs searched and the Nannies cried on each other’s shoulder, Mrs Dearly telephoned Mr Dearly. He came home at once, bringing with him one of the Top Men from Scotland Yard. The Top Man found a bit of sacking on the area railings and said the puppies must have been dropped into sacks and driven away in the black van. He promised to Comb the Underworld, but warned the Dearlys that stolen dogs were seldom recovered unless a reward was offered. A reward seemed an unreasonable thing to offer a thief, but Mr Dearly was willing to offer it.

He rushed to Fleet Street and had large advertisements put on the front pages of the evening papers (this was rather expensive) and arranged for even larger advertisements to be on the front pages of the next day’s morning papers (this was even more expensive). Beyond this, there seemed nothing he or Mrs Dearly could do except try to comfort each other and comfort the Nannies and the dogs. Soon the Nannies stopped crying and joined in the comforting, and prepared beautiful meals which nobody felt like eating. And, at last, night fell on the stricken household.

Worn out, the three dogs lay in their baskets in front of the kitchen fire.

‘Think of my baby Cadpig in a sack,’ said Missis, with a sob.

‘Her big brother Patch will take care of her,’ said Pongo, soothingly – though he felt most unsoothed himself.

‘Lucky is so brave he will bite the thieves,’ wailed Perdita. ‘And then they will kill him.’

‘No, they won’t,’ said Pongo. ‘The pups were stolen because they are valuable. No one will kill them. They are only valuable while they are alive.’

But even as he said this a terrible suspicion was forming in his mind. And it grew and grew as the night wore on. Long after Missis and Perdita, utterly exhausted, had fallen asleep, he lay awake staring at the fire, chewing the wicker of his basket as a man might have smoked a pipe.

Anyone who did not know Pongo well would have thought him handsome, amusing and charming, but not particularly clever. Even the Dearlys did not quite realise the depths of his mind. He was often still so puppyish. He would run after balls and sticks, climb into laps far too small to hold him, roll over on his back to have his stomach scratched. How was anyone to guess that this playful creature owned one of the keenest brains in Dogdom?

It was at work now. All through the long December night he put two and two together and made four. Once or twice he almost made five.

He had no intention of alarming Missis and Perdita with his suspicions. Poor Pongo! He not only suffered on his own account, as a father; he also suffered on the account of two mothers. (For he had come to feel the puppies had two mothers, though he never felt he had two wives – he looked on Perdita as a much-loved young sister.) He would say nothing about his worst fears until he was quite sure. Meanwhile, there was an important task ahead of him. He was still planning it when the Nannies came down to start another day.

As a rule, this was a splendid time – with the fire freshly made, plenty of food around and the puppies at their most playful. This morning – well, as Nanny Butler said, it just didn’t bear thinking about. But she thought about it, and so did everybody else in that pupless house.

No good news came during the day, but the Dearlys were surprised and relieved to find that the dogs ate well. (Pongo had been firm: ‘You girls have got to keep your strength up.’) And there was an even greater surprise in the afternoon. Pongo and Missis showed very plainly that they wanted to take the Dearlys for a walk. Perdita did not. She was determined to stay at home in case any pup returned and was in need of a wash.

Cold weather had come at last – Christmas was only a week away.

‘Missis must wear her coat,’ said Mrs Dearly.

It was a beautiful blue coat with a white binding; Missis was very proud of it. Coats had been bought for Pongo and Perdita, too. But Pongo had made it clear he disliked wearing his.

So the coat was put on Missis, and both dogs were dressed in their handsome chain collars. And then they put the Dearlys on their leashes and led them into the park.

From the first, it was quite clear the dogs knew just where they wanted to go. Very firmly, they led the way right across the park, across the road, and to the open space which is called Primrose Hill. This did not surprise the Dearlys as it had always been a favourite walk. What did surprise them was the way Pongo and Missis behaved when they got to the top of the hill. They stood side by side and they barked.

They barked to the north, they barked to the south, they barked to the east and west. And each time they changed their positions, they began the barking with three very strange, short, sharp barks.

‘Anyone would think they were signalling,’ said Mr Dearly.

But he did not really mean it. And they were signalling.

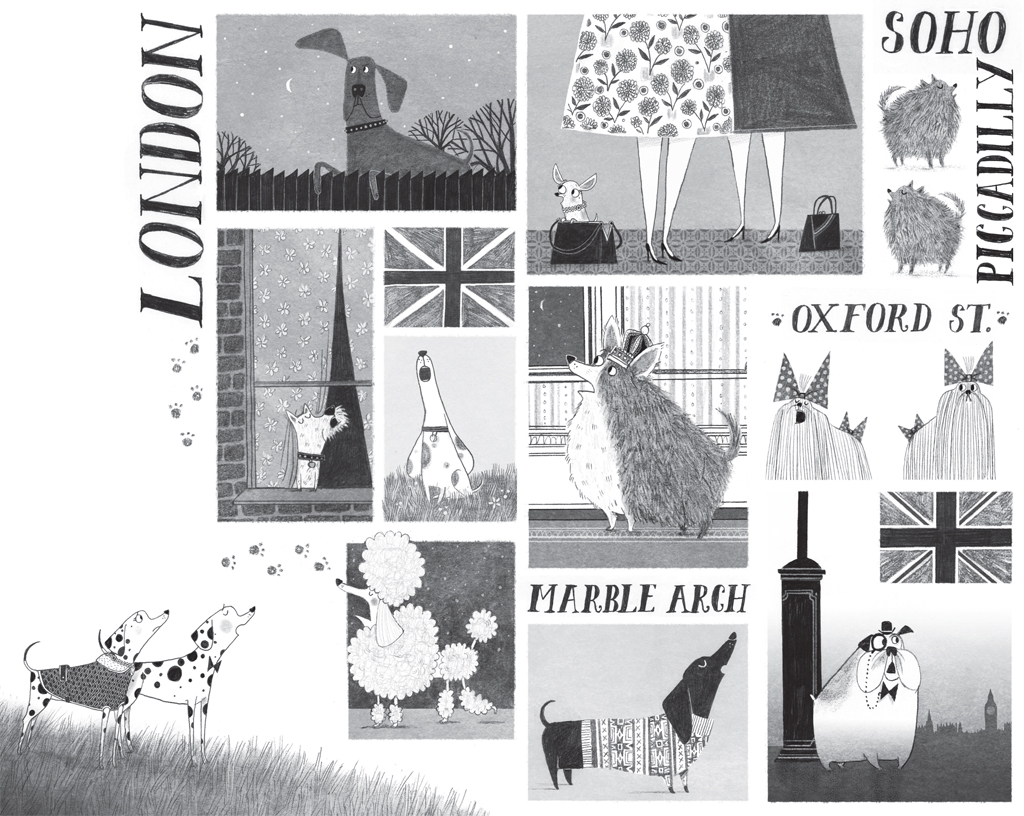

Many people must have noticed how dogs like to bark in the early evening. Indeed, twilight has sometimes been called ‘Dogs’ Barking Time’. Busy town dogs bark less than country dogs, but all dogs know all about the Twilight Barking. It is their way of keeping in touch with distant friends, passing on important news, enjoying a good gossip. But none of the dogs who answered Pongo and Missis expected to enjoy a gossip, for the three short, sharp barks meant: ‘Help! Help! Help!’

No dog sends that signal unless the need is desperate. And no dog who hears it ever fails to respond.

Within a few minutes, the news of the stolen puppies was travelling across England, and every dog who heard at once turned detective. Dogs living in London’s Underworld (hard-bitten characters; also hard-biting) set out to explore sinister alleys where dog thieves lurk. Dogs in Pet Shops hastened to make quite sure all puppies offered for sale were not Dalmatians in disguise. And dogs who could do nothing else swiftly handed on the news, spreading it through London and on through the suburbs, and on, on to the open country: ‘Help! Help! Help! Fifteen Dalmatian puppies stolen. Send news to Pongo and Missis Pongo, of Regent’s Park, London. End of Message.’

Pongo and Missis hoped all this would be happening. But all they really knew was that they had made contact with the dogs near enough to answer them, and that those dogs would be standing by, at twilight the next evening, to relay any news that had come along.

One Great Dane, over towards Hampstead, was particularly encouraging.

‘I have a chain of friends all over England,’ he said, in his great, booming bark. ‘And I will be on duty day and night. Courage, courage, O Dogs of Regent’s Park!’

It was almost dark now. And the Dearlys were suggesting – very gently – that they should be taken home. So, after a few last words with the Great Dane, Pongo and Missis led the way down Primrose Hill. The dogs who had answered them were silent now, but the Twilight Barking was spreading in an ever-widening circle. And tonight it would not end with twilight. It would go on and on as the moon rose high over England.

The next day, a great many people who had read Mr Dearly’s advertisements rang up to sympathise. (Cruella de Vil did, and seemed most upset when she was told the puppies had been stolen while she was talking to Nanny Cook.) But no one had anything helpful to say. And Scotland Yard was Frankly Baffled. So it was another sad, sad day for the Dearlys, the Nannies and the dogs.

Just before dusk, Pongo and Missis again showed that they wished to take the Dearlys for a walk. So off they started and again the dogs led the way to the top of Primrose Hill. And again they stood side by side and gave three sharp barks. But this time, though no human ear could have detected it, they were slightly different barks. And they meant, not ‘Help! Help! Help!’ but ‘Ready! Ready! Ready!’

The dogs who had collected news from all over London replied first. Reports had come in from the West End and the East End and South of the Thames. And all these reports were the same:

‘Calling Pongo and Missis Pongo of Regent’s Park. No news of your puppies. Deepest regrets. End of Message.’

Poor Missis! She had hoped so much that her pups were still in London. Pongo’s secret suspicion had led him to pin his hopes to news from the country. And soon it was pouring in – some of it relayed across London. But it was always the same:

‘Calling Pongo and Missis Pongo of Regent’s Park. No news of your puppies. Deepest regrets. End of Message.’

Again and again Pongo and Missis barked the ‘Ready!’ signal, each time with fresh hope. Again and again came bitter disappointment. At last only the Great Dane over towards Hampstead remained to be heard from. They signalled to him – their last hope!

Back came his booming bark:

‘Calling Pongo and Missis Pongo of Regent’s Park. No news of your puppies. Deepest regrets. End of –’

The Great Dane stopped in mid-bark. A second later he barked again: ‘Wait! Wait! Wait!’

Dead still, their hearts thumping, Pongo and Missis waited. They waited so long that Mr Dearly put his hand on Pongo’s head and said: ‘What about coming home, boy?’ For the first time in his life, Pongo jerked his head from Mr Dearly’s hand, then went on standing stock still. And at last the Great Dane spoke again, booming triumphantly through the gathering dusk.

‘Calling Pongo and Missis Pongo. News! News at last! Stand by to receive details.’

A most wonderful thing had happened. Just as the Great Dane had been about to sign off, a Pomeranian with a piercing yap had got a message through to him. She had heard it from a Poodle who had heard it from a Boxer who had heard it from a Pekinese. Dogs of almost every known breed had helped to carry the news – and a great many dogs of unknown breed (none the worse for that and all of them bright as buttons). In all, four hundred and eighty dogs had relayed the message, which had travelled over sixty miles as the dog barks. Each dog had given the ‘Urgent’ signal, which had silenced all gossiping dogs. Not that many dogs were merely gossiping that night; almost all the Twilight Barking had been about the missing puppies.

This was the strange story that now came through to Pongo and Missis: some hours earlier, an elderly English Sheepdog, living on a farm in a remote Suffolk village, had gone for an afternoon amble. He knew all about the missing puppies and had just been discussing them with the tabby cat at the farm. She was a great friend of his.

Some little way from the village, on a lonely heath, was an old house completely surrounded by an unusually high wall. Two brothers, named Saul and Jasper Baddun lived there, but were merely caretakers for the real owner. The place had an evil reputation – no local dog would have dreamed of putting its nose inside the tall iron gates. In any case, these gates were always kept locked.

It so happened that the Sheepdog’s walk took him past this house. He quickened his pace, having no wish to meet either of the Badduns. And at that moment, something came sailing out over the high wall.

It was a bone, the Sheepdog saw with pleasure; but not a bone with meat on it, he noted with disgust. It was an old, dry bone, and on it were some peculiar scratches. The scratches formed letters. And the letters were SOS.

Someone was asking for help! Someone behind the tall wall and the high, chained gates! The Sheepdog barked a low, cautious bark. He was answered by a high, shrill bark. Then he heard a yelp, as if some dog had been cuffed. The Sheepdog barked again, saying: ‘I’ll do all I can.’ Then he picked up the bone in his teeth and raced back to the farm.

Once home, he showed the bone to the tabby cat and asked her help. Then, together, they hurried to the lonely house. At the back, they found a tree whose branches reached over the wall. The cat climbed the tree, went along its branches, and then leapt to a tree the other side of the wall.

‘Take care of yourself,’ barked the Sheepdog. ‘Remember those Baddun brothers are villains.’

The cat clawed her way down, backwards, to the ground, then hurried through the overgrown shrubbery. Soon she came to an old brick wall which enclosed a stable yard. From behind the wall came whimperings and snufflings. She leapt to the top of the wall and looked down.

The next second, one of the Baddun brothers saw her and threw a stone at her. She dodged it, jumped from the wall and ran for her life. In two minutes she was safely back with the Sheepdog.

‘They’re there!’ she said, triumphantly. ‘The place is seething with Dalmatian puppies!’

The Sheepdog was a formidable Twilight Barker. Tonight, with the most important news in Dogdom to send out, he surpassed himself. And so the message travelled, by way of farm dogs and house dogs, great dogs and small dogs. Sometimes a bark would carry half a mile or more, sometimes it would only need to carry a few yards. One sharp-eared Cairn saved the chain from breaking by picking up a bark from nearly a mile away, and then almost bursting herself getting it on to the dog next door. Across miles and miles of country, across miles and miles of suburbs, across a network of London streets the chain held firm, from the depths of Suffolk to the top of Primrose Hill – where Pongo and Missis, still as statues, stood listening, listening.

‘Puppies found in lonely house. SOS on old bone –’ Missis could not take it all in. But Pongo missed nothing. There were instructions for reaching the village, suggestions for the journey, offers of hospitality on the way. And the dog chain was standing by to take a message back to the pups – the Sheepdog would bark it over the wall in the dead of night.

At first Missis was too excited to think of anything to say, but Pongo barked clearly: ‘Tell them we’re coming! Tell them we start tonight! Tell them to be brave!’

Then Missis found her voice: ‘Give them all our love! Tell Patch to take care of the Cadpig! Tell Lucky not to be too daring! Tell Roly Poly to keep out of mischief !’ She would have sent a message to every one of the fifteen pups if Pongo had not whispered: ‘That’s enough, dear. We mustn’t make it too complicated. Let the Great Dane start work now.’

So they signed off and there was a sudden silence. And then, though not quite so loudly, they heard the Great Dane again. But this time he was not barking towards them. What they heard was their message, starting on its way to Suffolk.

AS THEY WALKED the Dearlys home, Pongo said to Missis: ‘Did you hear who owns the house where the puppies are imprisoned?’

Missis said: ‘No, Pongo. I’m afraid I missed many things the Great Dane barked.’

‘I will tell you everything later,’ said Pongo.

He was faced with a problem. He now knew that his terrible suspicions were justified and it was time Missis learned the truth. But if he told her before dinner she might lose her appetite, and if he told her afterwards she might lose her dinner. So still he said nothing. And he made her eat every crumb of dinner and then join him in asking for more – which the Nannies gave with delight.

‘It may be a long time before we get another meal,’ he explained.

While the Nannies fed the Dearlys, the dogs made their plans. Perdita at once offered to come to Suffolk with them.

‘But you are still much too delicate for the journey, dear Perdita,’ said Missis. ‘Besides, what could you do?’

‘I could wash the puppies,’ said Perdita.

Both Pongo and Missis then said they knew Perdita was a beautiful puppy-washer but her job must be to comfort the Dearlys. And she felt that herself.

‘If only we could make them understand why we are leaving them!’ said Missis, sadly.

‘If we could do that, we shouldn’t have to leave them,’ said Pongo. ‘They would drive us to Suffolk in the car. And send the police.’

‘Oh, let us have one more try to speak their language,’ said Missis.

The Dearlys were sitting by the fire in the big white drawing-room. They welcomed the two dogs and offered them the sofa. But Pongo and Missis had no wish for a comfortable nap. They stood together, looking imploringly at the Dearlys.

Then Pongo barked gently: ‘Wuff, wuff, wuffolk!’

Mr Dearly patted him but understood nothing.

Then Missis tried: ‘Wuff, wuff, wuffolk!’

‘Are you telling us the puppies are in Suffolk?’ said Mrs Dearly.

The dogs wagged their tails wildly. But Mrs Dearly was only joking. It was hopeless and the dogs knew it always would be.

Dogs can never speak the language of humans and humans can never speak the language of dogs. But many dogs can understand almost every word humans say, while humans seldom learn to recognise more than half a dozen barks, if that. And barks are only a small part of the dog language. A wagging tail can mean so many things. Humans know that it means a dog is pleased, but not what a dog is saying about his pleasedness. (Really, it is very clever of humans to understand a wagging tail at all, as they have no tails of their own.) Then there are the snufflings and sniffings, the pricking of ears – all meaning different things. And many, many words are expressed by a dog’s eyes.

It was with their eyes that Pongo and Missis spoke most that evening, for they knew the Dearlys could at least understand one eye-word. That word was ‘love’ and the dogs said it again and again, leaning their heads against the Dearlys’ knees. And the Dearlys said ‘Dear Pongo’, ‘Dear Missis’, again and again.