Полная версия

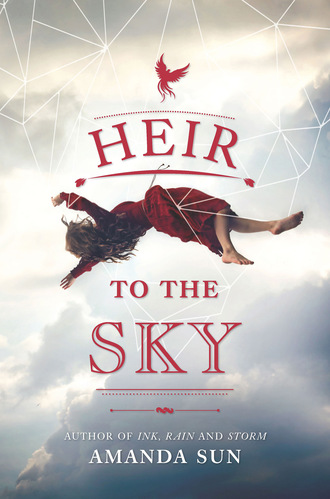

Heir To The Sky

I follow my father through the hallway, and then we are upon the steps of the citadel. The sunlight is blinding after the darkness of the corridors. The minstrels are plucking at the goat-string harps and the trumpets are blaring as the crowds cheer for their Monarch. Father looks noble and kind as he descends the steps toward the crowd. I wait at the doorway and watch him. Banners of crimson stream in the wind, and the giant statue of the Phoenix towers over the courtyard. There are garlands of flowers strung around her neck and bouquets of red and orange laid at her feet.

It seems a little ridiculous to me at times, but the annals and my governesses have always been clear—without her, mankind would have perished, consumed by the monsters that overrun the earth below. She saved us all with her sacrifice, and so we celebrate the Rending every year since, commemorating our deliverance from certain death.

My father has reached Elder Aban in the courtyard below, and the trumpets blare loudly as the crowd looks up for me. I take a deep breath and grasp the plume staff tightly, walking slowly down the stone stairs in my bare feet, one clean, one scuffed and dirty. I long to glance at Aban’s reaction, but I know I must look straight ahead into the crowd, smiling gently and looking wiser than I feel. The steps are grainy and rough and scrape the soles of my feet. Despite the bright sunny weather, the stone stairs are cold from the thin air up here in Ashra.

The crowd and minstrels are quiet, staring at me as I descend. I think only of how ridiculous it would look if I tripped headfirst, or if I burst into dance or suddenly turned and ran. I could end this whole ceremony, I think. It’s not that I want to destroy it, but the potential, just knowing I could do so, swirls endlessly in my head.

At last I reach the bottom step, and the crowds bow their heads. It all seems too silly to me. I walk through the village all the time with Elisha and no one bows to me. But today there’s such a separation I can feel it. They bend around me like heat bends around the wavering flame of a candle.

The Elite Guard stand in crisp rows to the side of the Phoenix statue. They’re dressed in uniforms of the customary white, with a single red plume pinned to their lapels. Some have golden pins or medals of iridescent shell depending on rank.

I see him immediately, of course. Jonash. He’s in the front row, at the right side of the lieutenant. It’s hard to miss him. He’s looking at me, too, his blue eyes shining and his dirty blond hair cropped neatly on his head. But there’s no time to think about him now. Aban has come toward me to receive the plume staff, and I place it in his old, shaking hands while my father reads from the pages of the annal.

His voice resonates through the courtyard. “So it was,” he reads, “that in those days, the land was covered with the thick darkness of a plague brewing. They came from every direction—creatures bent on destroying mankind and civility. On four legs, on six, on wings and in scales, above and beneath the surface of the earth. They knew only hunger, blood and malevolence.”

Elder Aban steps toward the Phoenix statue with my plume staff. I clasp my hands together over my dirt-stained dress, standing as still as I can. I can feel Jonash’s eyes on me, but I dare not look. I pretend that he’s not there at all, that he doesn’t even exist.

My father’s voice rises as he reads from the gilded tome. “But there was one creature who lived in light, not in darkness. In flame, not in bitter ice. There was one who was merciful and generous and giving. She saw our plight and took pity us. She gathered us under her wings, to protect us from the foul monsters outside.”

The people stare blankly ahead. We’ve heard this story. We hear it every year. But it’s distant to us. It happened nearly three hundred years ago. Well, two hundred and ninety-nine. We’ve never seen the monsters written about in the annals. We don’t even know if it’s true.

“The people walked from the mountains, from the valleys, from the oceans and the islands. We gathered upon this place, Ashra, when it was then part of the earth.”

Aban has placed the plume staff at the Phoenix’s stone talons and is backing away with his head bowed toward her. There is a small string in his hands, almost invisible unless you know it’s there. This is the big finale, the culmination of the Rending Ceremony.

“And then,” my father’s voice booms, “with a blast of her fiery wings, she tore the roots from the ground and rent the earth in two.” Aban pulls the string, and the plume staff erupts in a burst of flames that travels up the garlands around the statue. “She lifted us high above the darkness and the fangs and the endless hunger that infested the earth. She burned to ashes like the sun, raising us to freedom and deliverance.”

“May she rise anew!” the crowd shouts as the rings of fire blaze around the statue. The people cheer and wave their red banners as my father hands the annal to Aban, who closes the book and lifts it into the sky. I step toward the statue now, the flames dangerously close. My face is hot from the waves emanating from the fire. But this is proof of the Phoenix’s favor, and I must do this task to instill courage in the village. I quickly reach my hand toward the plume staff, now only a gold handle with a burned quill end attached to it. The longer I hesitate, the hotter the gold will get, so before I can rethink it I wrap my fingers around the handle and pull it away from the statue’s talons. I lift it high above my head like a baton, my headdress tinkling in my ears as the crowd cheers.

“From fiery sacrifice to ash, from ash to rebirth,” my father shouts, “we, too, will rise anew! Let us never return to those dark days. Let us never throw away the gift of a new rebirth on Ashra and in the skies!”

The people cheer, and Aban nods, and the official ceremony is over. Now is when my father usually ascends the steps and I follow, but today he’s got more news to share. I see him look at me for a moment, his eyes kind and a little remorseful. And there’s nothing I can do but nod, because our lives are for the people, and I know this. We are the wick and wax, and we still burn for Ashra’s freedom.

“There is one more announcement you’ve been waiting for,” my father says, raising his hands. The elaborate red-and-gold sleeves coil around his elbows and the crowd quiets down. He looks toward the Elite Guard, and the lieutenant salutes. He marches smartly into the courtyard, then turns sharply to face the crowd. When he glances at his troop, Jonash steps forward. He doesn’t march the way the lieutenant did, but walks gracefully and solemnly toward us.

“Next year is the Three Hundredth Anniversary of the Rending,” Father says. “And it is time to secure the continuation of Ashra and her lands—Burumu, Nartu and the Floating Isles.” Ashra had been the original continent—the others broke off during the Rending and sailed through the sky, shattered shards of a broken past.

But it’s the future that concerns me now.

Jonash’s eyes burn as intensely as the last of the flames that devour the garlands around the Phoenix. He falls to a knee before my father, who nods at him.

“I am pleased to officially announce,” my father says, each word an iron link in my chain, “the betrothal of my daughter, Princess Kallima of Ashra, to Second Lieutenant Jonash, son of the Sargon of Burumu.”

Jonash’s eyes meet mine, and his hand rises palm up like an offering. I know what is expected of me. I rest my hand in his, and he presses his forehead against the backs of my fingers. His skin is cool from the breeze, but my fingers are warm from the golden staff fetched from the fire.

The people cheer and applaud as Jonash rises to his feet and stands just behind me. The Sargon is lower ranking than my father the Monarch, but Burumu has the densest population and the greatest output of resources that complement Ashra’s agriculture. The union is perfect to continue the peaceful ruling of the floating kingdom on which our lives play out.

Jonash’s hand rests in mine as we ascend the steps behind my father, the cold stone scraping against my bare feet. I feel as though I have changed into someone else just now, as if I have ceased to exist.

The candle of my life burns, tears of wax trickling down its melting sides.

THREE

JONASH DOESN’T SPEAK to me until we are inside the great room, where my father and I stretch out our arms, and the attendants begin to unravel the cumbersome costumes that adorn us.

“Kallima,” he says. “It’s a pleasure to see you again.”

“And you,” I answer, always diplomatic and polite as I am supposed to be. Two attendants come to lift the headdress off my head, untangling the strings of beads that have twisted and knotted into my hair. But with Jonash here, I don’t feel any lighter. The world still feels stiff and heavy. “How was the journey from Burumu?”

He smiles, his blue eyes full of warmth and his cheeks flushed with a bashful glow. Elisha is right when she says he’s handsome, but his looks don’t move me at all. “It was well enough. Airships are bumpy, troublesome things.”

I haven’t been on one since I was seven years old, when I toured Burumu and Nartu with my father for the 290th Anniversary of the Rending. The airships are patched together like the hot air balloons I’ve read about in the annals, and they float from side to side in a pudgy, indecisive path. I’d wanted to see the ocean below Burumu on that journey, but the clouds were thick that day, only the peaks of the mountain range poking through. I remember how wonderful it was to look out at the lesser floating isles, though, the small pieces of continent that are too rocky or inhospitable for people to live on or gather resources from. They looked so strange, their roots and crumbling soil holding on to nothingness as they floated in the air.

“How are things in Burumu, Jonash?” my father says as I duck my head down so the attendants can untangle the last strings of the headdress from my hair.

“Well, thank you,” Jonash answers. “My father sends his regards, and his apologies that he could not attend the ceremony.”

My father laughs gently, his warm eyes twinkling as his skin crinkles. “We understand the burden of the Sargon. Burumu is a bustling place.”

“Yes,” Jonash answers. “He does his best to deal with the unrest.”

“Unrest?” I say. My father frowns, his gray beard drooping with the expression. This is the first I’ve heard of this unrest. And my father has never been one to coddle or patronize me. In fact, he’s always kept me well involved in political affairs. I’m the next in line, after all. Ignorance wouldn’t suit either of us.

“Nothing to trouble Your Highness, of course,” Jonash says quickly. “It’s nothing more than a trifling thought. Burumu is a larger city than Ulan, and sometimes the past weighs heavily upon our shoulders.”

Burumu is a larger city, this much is true. On Ashra we have Lake Agur, the rolling hills full of wildflowers and the comfort of the Phoenix statue and citadel. Ours is a farming community protected from the harsh winds by a sheer mountain range on the northeast side. There is too much to do in a day to sit around and talk about unrest. But Burumu is a city of resources, where they mine gold and smelt iron and copper. It’s where the airships are assembled, and the land is scarcer. Many of the families in Burumu try to immigrate to Ashra, but we need to preserve the continent so that future generations won’t run out of food. Is this the source of the unrest? We strive hard not to allow inequality in the kingdom, but there will always be some jobs more desirable than others to sustain the community.

I shake my head in disbelief, putting on my best regal voice. “We know what it is to have a common enemy, the monsters that drove us into the skies. We know that to squabble among ourselves would be to ignore the gift of freedom the Phoenix has given us.”

“My daughter is right, as always.” My father smiles. “The situation in Burumu is nothing more than that—a tiny squabble before the past is remembered. Otherwise the Sargon would be quite bored, with nothing to manage.”

I feel uneasy. My father is lying, I’m sure of it, and whether it’s to me or to Jonash is the question. But the conversation has ended, and to continue it would be to embarrass him in front of company. I’ll ask him later, when it’s just the two of us.

“Indeed Burumu keeps one busy,” Jonash ends politely, but his eyes never leave me. “It’s always a pleasure to get away for a while and to seek other joys.”

He means well, I know. He’s charming, polite and well mannered. He’s handsome and intelligent. But I don’t feel anything for him, no matter how hard I try. He’s like the floating continents—beauty and pageantry above, and no substance below. It makes me sad to think this, and I’m flooded with guilt. I haven’t even given him a chance.

I attempt a smile, feeling like a complete fake.

“Your Highness,” he says, but I shake my head.

“Kali is fine. There’s no need for formalities now the ceremony is done.”

“I suppose not,” he says. “Then, Kali, might I request the pleasure of your company tonight?” His cheeks blaze, and every word from his mouth is slow and thoughtful. “I’d hoped to visit Ulan and see more of Ashra. The Elite Guard will be staying a few days to partake in the celebrations, but I’m afraid I won’t feel festive when I don’t know anyone in the crowds.”

He smiles, but my stomach twists. I’ll have to spend more and more time with him, until we’re married next year. And then we’ll live together in the citadel, and we’ll be looked on to provide a happy example to the people. We’ll share every meal, every moment, every night. We’ll have heirs to keep the bloodline going. My face warms. Perhaps I can learn to love him, I think. I desperately will myself to love him, to make this easier.

I don’t. But maybe I could. Someday.

Or maybe not.

“I’m afraid I’d had plans with my friend Elisha...” I begin, and I can’t believe the words are flowing out of my mouth. My father won’t approve of my discourtesy.

Jonash’s face turns pale; his warm eyes falter. “I... I see,” he says, his fingers fumbling across the golden plume pinned to his lapel. “Of course I understand. I...”

“Oh, ashes and soot,” my father chimes in from the corner. “Elisha can go with you, can’t she? It wouldn’t be proper without a chaperone anyway.”

Jonash hesitates, uncertain how to respond.

But I know what to do. I know what my father has gently asked of me.

“Well, then,” I say with regret. “I’d be delighted to accept.”

“I... Oh. Wonderful,” Jonash says. He’s lost in the silent conversation between my father and me, the words unspoken that duty comes first. He nods his head. “Shall we meet at the fountain, then, after dinner?”

“Won’t you dine with us tonight, Jonash?” my father says. “I couldn’t forgive myself if I treated my son-in-law-to-be with such discourtesy as to leave him to scavenge for his own supper.”

“My gratitude to you, Monarch,” Jonash answered. “But it’s the lieutenant’s birthday, and he’s asked us to join him for the occasion. Er... I’m certain I could explain to him.”

I roll my eyes. It seems eloquence isn’t one of Jonash’s better skills. “That isn’t necessary,” I pipe up pleasantly. “You can always join us tomorrow.”

Both men look at me gratefully, and I wonder what we’re all actually thinking. Does Jonash feel as I do about the arranged engagement? Does he have someone he cares for on Burumu? If he does, or if he longs for freedom like me, then he hides it well. If he, too, burns for the people, I can’t even see the wax tears dripping from the light of the wick.

“At the fountain, then,” he says. “When the skies are darkening. I’ll wait.”

I force another smile, and an attendant escorts him out.

FOUR

ONCE JONASH IS GONE, and my father has been pulled away by the Elders and their pressing Rending Ceremony matters, I’m finally alone and free. I step barefoot through the dim hallways, twisting toward the library in the north. Except for the outcrop on the edge of the continent, the library is my most favorite refuge. Hardly anyone bothers these days with the dusty tomes and endless red annals stacked along the back shelves. There’s no need to look into the past anymore. Life is busy enough to just survive the present.

But I love to read the rich stories of the earth and the world before the Rending. I want to dive into the oceans teeming with rainbow fish and turtles and dolphins. I want to feel the soft manes of horses, which seem to be a type of giant goat, and the striped tails of the raccoons. I want to know about the cities that used to be, ones where thousands of people lived all in one place. I want to know about the strange customs and technologies that have been lost to us for nearly three hundred years. And just once, perhaps, I’d like to see a dragon, or how small the two moons must look, gleaming down onto a world so far below the floating continents.

The oldest annals are difficult to read because the language is archaic and the print faded. I’ve asked the Elders for help, but even Aban doesn’t have the knowledge to read them. It’s surprising, really, because the original Elders were the first to write things down at the beginning of the Rending, to keep track of old memories and wisdom from earth to save our heritage. You’d think the Elders would have taught each other as they went along, keeping the knowledge alive.

I run my fingers along the tops of the tomes, aching to know what’s written in the gold-edged pages. I grab the fiftieth one in the row, the one where the language is almost readable. I open it up about one hundred pages in, where one of my favorite illustrations is splashed on the page. The manuscripts hold so few images, but this is one where the Elder scribe couldn’t help himself. He has imagined what the ocean would look like, a lake without end. He’s drawn what he imagines sea snakes and dolphins and fish to look like, and he’s painted them all with the reddish-brown iron ink they manufacture in Burumu. He’s tried his best to be accurate, but he’s never seen the ocean, either, except for glimpses from the edge of the continent. We have fish in our lakes, but I imagine the ones in the ocean are larger and vividly colored, splashing about with fangs and fins and glittering scales. I wonder if his sketch is even close to what sea creatures really look like, frothing about against the shore.

I fit the book neatly in its space on the shelf and take out the very first of the annals. I’ve looked at it many times before, but its faded ancient letters just stare back at me, their looping script holding secrets I can’t unlock. I run my fingers along the red text, flipping the crinkled pages slowly. There’s a single illustration in this tome, on the ninetieth page. It shows the bottom of the continent Ashra, the roots of the trees bound in a tangle around the dirt that lifts into the sky. There is a fissure sketched in, where Burumu and Nartu are breaking off from Ashra under the pressure of the Rending. Below the continent the Phoenix rises into the air. Her dark red-brown wings gleam with a cloud of sketched glory, and she clasps monsters of every type in her talons. They are miniscule in the drawing, but I can make out twisting horns, slithering limbs and feathers. A great hole has been ripped in the earth below her, and along the rim of the hole tiny sketches of people wail upon their knees, reaching out for Ashra as it rises up. These were the unbelievers, who didn’t heed her call and were devoured by the monsters. I press my thumbnail against them, thinking how small they are. I pity them, but I envy them, too. They knew about the oceans and the mountains. They knew all the things I wish to know. Even if their lives ended in despair, they were free until that last bitter moment.

No, I think. There’s no freedom in being hunted down. Their lives were forfeit before they were even born.

A shuffling in the library startles me. It’s always quiet here, especially when everyone must be out celebrating the Rending. I quietly slide the first of the annals back into its place on the shelves so I can peek at who’s approaching.

I call out softly. “Elisha?” Maybe she’s searching for me to talk about Jonash and the engagement. But then I hear two men’s voices arguing just beyond hearing. Something doesn’t feel right, and I shrink behind the shelf as they approach.

“One of the Initiates must have said something,” the first voice says.

The second one snaps, “We don’t share it with the Initiates. It’s reserved only for the senior Elders.”

That’s Aban’s voice. I’d know it anywhere. A moment later, Aban steps into view, his cream robe swishing against the floor and the tassels of his red belt pounding against him with every step.

“Then how did it reach them?” the first man says. He stands in a crisp white uniform, two dark red plumes laid on either shoulder and a gold chain draped over his chest. The lieutenant of the Elite Guard. Why would he be here? Jonash had said they would be out to celebrate his birthday, but the lieutenant’s brow is creased and his face anxious. The Elders use the library all the time, but I’ve never seen anyone from the Elite Guard set foot in these dusty stacks of tomes.

“It can only be the work of an Elder,” the lieutenant insists. “The others cannot read the early texts.”

“The Elders are loyal to the Monarch,” Aban spits back. “They would never join the rebels.”

Rebels? Rebelling against what? I wonder. Life on Ashra and her lands is peaceful, with no need to rebel.

“An exile, then,” the first voice says.

Aban shakes his head. “And how do you suppose they got off Nartu?”

It’s the first I’ve heard of exiled Elders. It’s true that the life isn’t for everyone, but Elders who retire or Initiates who give up their instruction often choose a life of solitude on Nartu. Don’t they?

“It is your fault for not keeping Burumu under control,” Aban says. “The rebellions should have been quashed by now, not spreading. And if they’ve learned of this!”

Learned of what? And who has read the early texts? Too many questions flood into my mind at once. I think of the unrest Jonash mentioned, the one my father hesitated to mention in front of me. Is it so serious as to pit the tempers of Aban and the lieutenant against each other? The Elite Guard and the Elders have always worked together to serve the lands of Ashra. All our roles build the Phoenix together to protect its beating heart, our people. And what the lieutenant suggests is ridiculous. Even the Elders can’t read the earliest texts.

None of it makes sense. But if the unrest is bad enough to worry either group and make them accuse each other, then there is more happening than my father has let on.

My thoughts muddle with confusion as I peek over the tops of the annals. Aban and the lieutenant have stopped at a small desk on the other side, where the Elders occasionally place the annals to study them. Aban reaches around his neck and produces a small key on a string. I’ve never noticed a key around Aban’s neck before. He turns toward a cupboard near the desk and fits in the key, turning it with a creak. He rustles through the darkness and produces a bloodred tome with gilded pages. It looks just like the rows of annals on the shelf, and every volume is accounted for. Why would there be one locked in the cupboard?

Aban lifts it onto the desk with an echoing thud and begins to flip the pages.

“I’m telling you,” the lieutenant tries again. Aban whispers to himself in what sounds like a foreign tongue, his eyes scanning the words as his finger runs down the page.

My hand goes to my open mouth. He’s reading the ancient script. He’s reading the early annals.