Полная версия

A Good Girl's Guide to Murder

First published in Great Britain in 2019

by Electric Monkey, an imprint of Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2019 Holly Jackson

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978 1 4052 9318 1

Ebook ISBN 978 1 4052 9384 6

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

Egmont takes its responsibility to the planet and its inhabitants very seriously. We aim to use papers from well-managed forests run by responsible suppliers.

To Mum and Dad,

this first one is for you.

Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

Part I

One

Production Log – Entry 1

Transcript of interview with Angela Johnson from the Missing Persons Bureau

Two

Production Log – Entry 2

Three

Production Log – Entry 3

Transcript of interview with Stanley Forbes from the Kilton Mail newspaper

Four

Production Log – Entry 4

Transcript of interview with Ravi Singh

Production Log – Entry 5

Five

Production Log – Entry 7

Transcript of interview with Max Hastings

Six

Production Log – Entry 8

Transcript of interview with Elliot Ward

Seven

Eight

Nine

Production Log – Entry 11

Transcript of interview with Chloe Burch

Ten

Eleven

Part II

Twelve

Production Log – Entry 13

Transcript of second interview with Emma Hutton

Thirteen

Production Log – Entry 15

Transcript of second interview with Naomi Ward

Fourteen

Production Log – Entry 17

Production Log – Entry 18

Fifteen

Production Log – Entry 19

Production Log – Entry 20

Transcript of interview with Jess Walker (Becca Bell’s friend)

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Production Log – Entry 22

Nineteen

Twenty

Production Log – Entry 23

Twenty-One

Production Log – Entry 24

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Production Log – Entry 25

Production Log – Entry 26

Twenty-Four

Production Log – Entry 27

Production Log – Entry 28

Production Log – Entry 29

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Part III

Production Log – Entry 31

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Production Log – Entry 33

Thirty-One

Production Log – Entry 34

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

The Months Later

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

About the Author

One

Pip knew where they lived.

Everyone in Little Kilton knew where they lived.

Their home was like the town’s own haunted house; people’s footsteps quickened as they walked by and their words strangled and died in their throats. Shrieking children would gather on their walk home from school, daring one another to run up and touch the front gate.

But it wasn’t haunted by ghosts, just three sad people trying to live their lives as before. A house not haunted by flickering lights or spectral falling chairs, but by dark spray-painted letters of Scum Family and stone-shattered windows.

Pip had always wondered why they didn’t move. Not that they had to; they hadn’t done anything wrong. But she didn’t know how they lived like that.

Pip knew a great many things; she knew that hippopotomonstrosesquipedaliophobia was the technical term for the fear of long words, she knew that babies were born without kneecaps, she knew verbatim the best quotes from Plato and Cato, and that there were more than four thousand types of potato. But she didn’t know how the Singhs found the strength to stay here. Here, in Kilton, under the weight of so many widened eyes, of the comments whispered just loud enough to be heard, of neighbourly small talk never stretching into long talk any more.

It was a particular cruelty that their house was so close to Little Kilton Grammar School, where both Andie Bell and Sal Singh had gone, where Pip would return for her final year in a few weeks when the August-pickled sun dipped into September.

Pip stopped and rested her hand on the front gate, instantly braver than half the town’s kids. Her eyes traced up the path to the front door. It might only look like a few feet but there was a rumbling chasm between where she stood and over there. It was possible that this was a very bad idea; she had considered that. The morning sun was hot and she could already feel her knee pits growing sticky in her jeans. A bad idea or a bold idea. And yet, history’s greatest minds always advised bold over safe; their words good padding for even the worst ideas.

Snubbing the chasm with the soles of her shoes, she walked up to the door and, pausing for just a second to check she was sure, knocked three times. Her tense reflection stared back at her: the long dark hair sun-dyed a lighter brown at the tips, the pale face, despite a week just spent in the south of France, the sharp muddy green eyes braced for impact.

The door opened with the clatter of a falling chain and a double-locked click.

‘Hello?’ he said, holding the door half open, his hand folded over the side. Pip blinked to break her stare, but she couldn’t help it. He looked so much like Sal: the Sal she knew from all those television reports and newspaper pictures. The Sal fading from her adolescent memory. Ravi had his brother’s messy black side-swept hair, thick arched eyebrows and oaken-hued skin.

‘Hello?’ he said again.

‘Um . . .’ Pip’s put-on-the-spot charmer reflex kicked in too late. Her brain was busy processing that, unlike Sal, he had a dimple in his chin, just like hers. And he’d grown even taller since she last saw him. ‘Um, sorry, hi.’ She did an awkward half-wave that she immediately regretted.

‘Hi?’

‘Hi, Ravi,’ she said. ‘I . . . you don’t know me . . . I’m Pippa Fitz-Amobi. I was a couple of years below you at school before you left.’

‘OK . . .’

‘I was just wondering if I could borrow a jiffy of your time? Well, not a jiffy . . . Did you know a jiffy is an actual measurement of time? It’s one one-hundredth of a second, so . . . can you maybe spare a few sequential jiffies?’

Oh god, this is what happened when she was nervous or backed into a corner; she started spewing useless facts dressed up as bad jokes. And the other thing: nervous Pip turned four strokes more posh, abandoning middle class to grapple for a poor imitation of upper. When had she ever seriously said ‘jiffy’ before?

‘What?’ Ravi asked, looking confused.

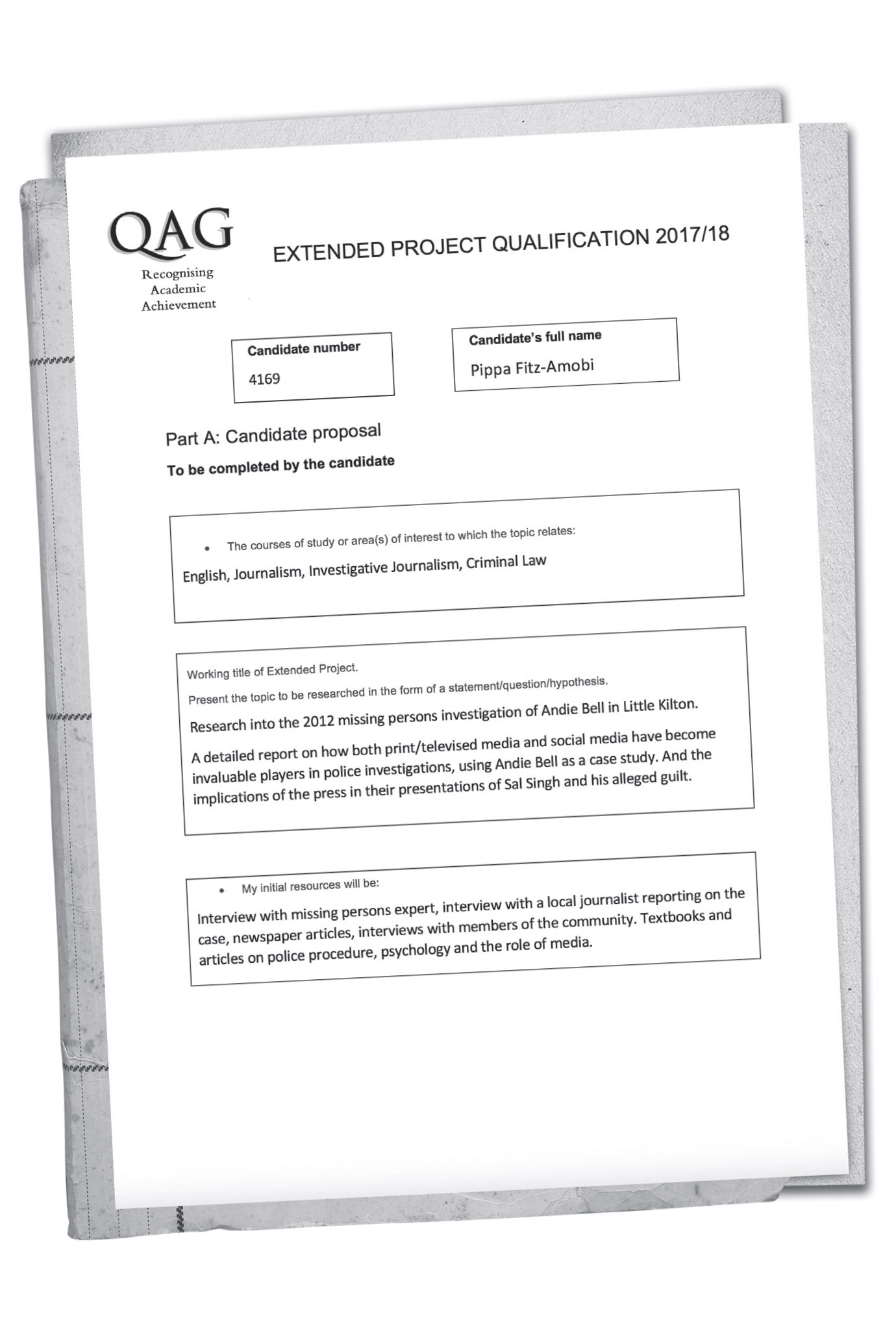

‘Sorry, never mind,’ Pip said, recovering. ‘So I’m doing my EPQ at school and –’

‘What’s EPQ?’

‘Extended Project Qualification. It’s a project you work on independently, alongside A levels. You can pick any topic you want.’

‘Oh, I never got that far in school,’ he said. ‘Left as soon as I could.’

‘Er, well, I was wondering if you’d be willing to be interviewed for my project.’

‘What’s it about?’ His dark eyebrows hugged closer to his eyes.

‘Um . . . it’s about what happened five years ago.’

Ravi exhaled loudly, his lip curling up in what looked like pre-sprung anger.

‘Why?’ he said.

‘Because I don’t think your brother did it – and I’m going to try to prove it.’

Pippa Fitz-Amobi

EPQ 01/08/2017

Production Log – Entry 1

Interview with Ravi Singh booked in for Friday afternoon (take prepared questions).

Type up transcript of interview with Angela Johnson.

The production log is intended to chart any obstacles you face in your research, your progress and the aims of your final report. My production log will have to be a little different: I’m going to record all the research I do here, both relevant and irrelevant, because, as yet, I don’t really know what my final report will be, nor what will end up being relevant. I don’t know what I’m aiming for. I will just have to wait and see what position I am in at the end of my research and what essay I can therefore bring together. [This is starting to feel a little like a diary???]

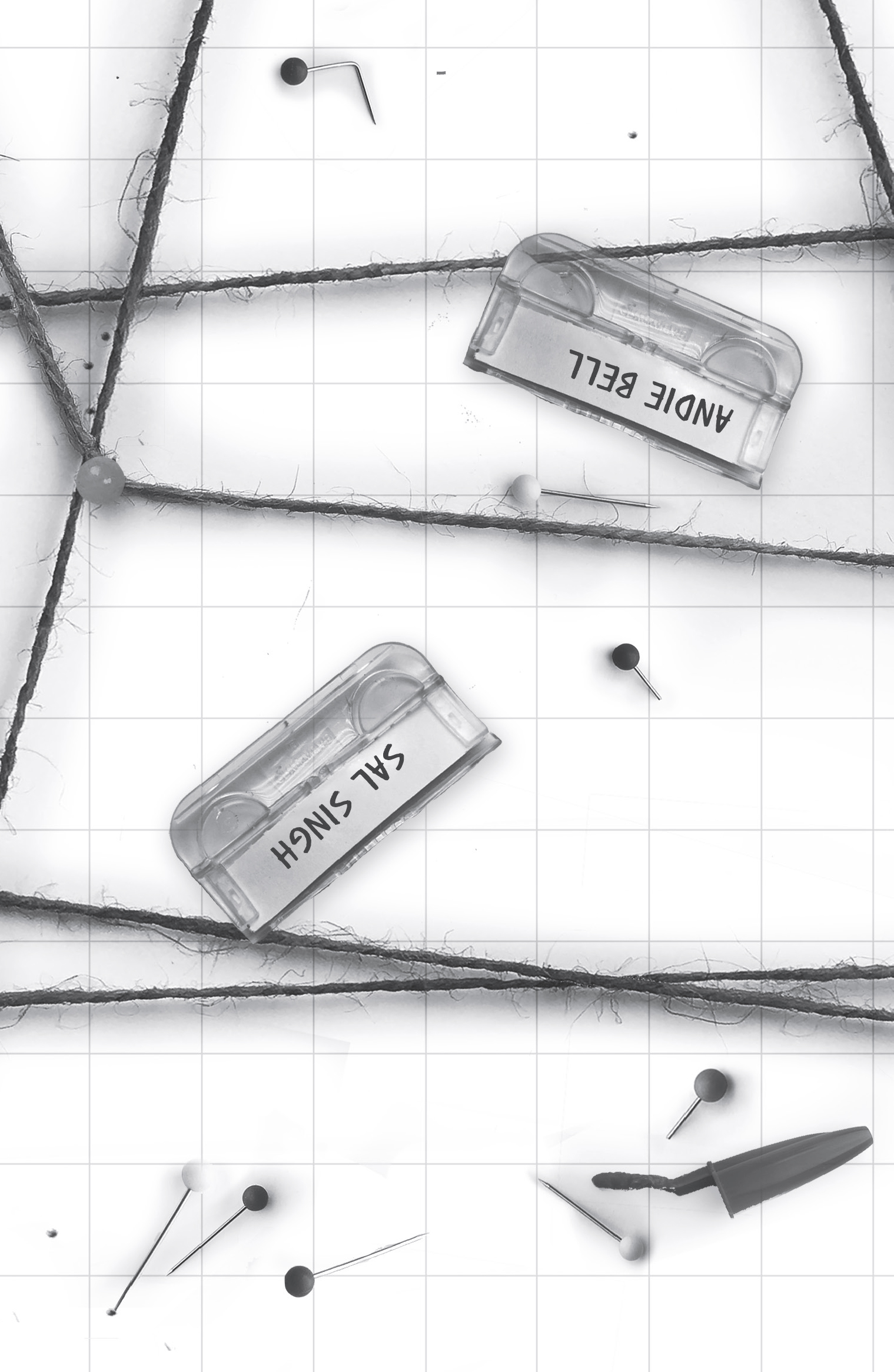

I’m hoping it will not be the essay I proposed to Mrs Morgan. I’m hoping it will be the truth. What really happened to Andie Bell on the 20th April 2012? And – as my instincts tell me – if Salil ‘Sal’ Singh is not guilty, then who killed her?

I don’t think I will actually solve the case and discover the person who murdered Andie. I’m not a police officer with access to a forensics lab (obviously) and I am also not deluded. But I’m hoping that my research will uncover facts and accounts that will lead to reasonable doubt about Sal’s guilt, and suggest that the police were mistaken in closing the case without digging further.

So my research methods will actually be: interviewing those close to the case, obsessive social media stalking and wild, WILD speculation.

[DON’T LET MRS MORGAN SEE ANY OF THIS!!!]

The first stage in this project then is to research what happened to Andrea Bell – known as Andie to everyone – and the circumstances surrounding her disappearance. This information will be taken from news articles and police press conferences from around that time.

[Write your references in now so you don’t have to do it later!!!]

Copied and pasted from the first national news outlet to report on her disappearance:

‘Andrea Bell, 17, was reported missing from her home in Little Kilton, Buckinghamshire, last Friday.

She left home in her car – a black Peugeot 206 – with her mobile phone, but did not take any clothes with her. Police say her disappearance is “completely out of character”.

Police have been searching woodland near the family home over the weekend.

Andrea, known as Andie, is described as white, five feet six inches tall, with long blonde hair. It is thought that she was wearing dark jeans and a blue cropped jumper on the night she went missing.’1

After everything happened, later articles had more detail as to when Andie was last seen alive and the time window in which she is believed to have been abducted.

Andie Bell was ‘last seen alive by her younger sister, Becca, at around 10:30 p.m. on the 20th April 2012.’2

This was corroborated by the police in a press conference on Tuesday 24th April: ‘CCTV footage taken from a security camera outside STN Bank on Little Kilton High Street confirms that Andie’s car was seen driving away from her home at about 10:40 p.m.’3

According to her parents, Jason and Dawn Bell, Andie was ‘supposed to pick (them) up from a dinner party at 12:45 a.m.’ When Andie didn’t show up or answer any of their phone calls, they started ringing her friends to see if anyone knew of her whereabouts. Jason Bell ‘called the police to report his daughter missing at 3:00 a.m. Saturday morning.’4

So whatever happened to Andie Bell that night, happened between 10:40 p.m. and 12:45 a.m.

Here seems a good place to type up the transcript from my telephone interview yesterday with Angela Johnson.

Transcript of interview with Angela Johnson from the Missing Persons Bureau

Angela: Hello. Pip: Hi, is this Angela Johnson? Angela: Speaking, yep. Is this Pippa? Pip: Yes, thanks so much for replying to my email. Angela: No problem. Pip: Do you mind if I record this interview so I can type it up later to use in my project? Angela: Yeah, that’s fine. I’m sorry I’ve only got about ten minutes to give you. So what do you want to know about missing persons? Pip: Well, I was wondering if you could talk me through what happens when someone is reported missing? What’s the process and the first steps taken by the police? Angela: So, when someone rings 999 or 101 to report someone as missing, the police will try to get as much detail as possible so they can identify the potential risk to the missing person and an appropriate police response can be made. The kinds of details they will ask for in this first call are name, age, description of the person, what clothes they were last seen wearing, the circumstances of their disappearance, if going missing is out of character for this person, details of any vehicle involved. Using this information, the police will determine whether this is a high-, low- or medium-risk case. Pip: And what circumstances would make a case high-risk? Angela: If they are vulnerable because of their age or a disability, that would be high-risk. If the behaviour is out of character, then it is likely an indicator that they have been exposed to harm, so that would be high-risk. Pip: Um, so, if the missing person is seventeen years old and it is deemed out of character for her to go missing, would this be considered a high-risk case? Angela: Oh, absolutely, if a minor is involved. Pip: So how would the police respond to a high-risk case? Angela: Well, there would be immediate deployment of police officers to the location the person is missing from. The officer will have to acquire further details about the missing person, such as details of their friends or partners, any health conditions, their financial information in case they can be found when trying to withdraw money. They will also need a number of recent photographs of the person and, in a high-risk case, they may take DNA samples in case they are needed in subsequent forensic examination. And, with consent of the homeowners, the location will be searched thoroughly to see if the missing person is concealed or hiding there and to establish whether there are any further evidential leads. That’s the normal procedure. Pip: So immediately the police are looking for any clues or suggestions that the missing person has been the victim of a crime? Angela: Absolutely. If the circumstances of the disappearance are suspicious, officers are always told ‘if in doubt, think murder.’ Of course, only a very small percentage of missing person cases turn into homicide cases, but officers are instructed to document evidence early on as though they were investigating a homicide. Pip: And after the initial home address search, what happens if nothing significant turns up? Angela: They will expand the search to the immediate area. They might request telephone information. They’ll question friends, neighbours, anyone who may have relevant information. If it is a young person, a teenager, who’s missing, a reporting parent cannot be assumed to know all of their child’s friends and acquaintances. Their peers are a good port of call to establish other important contacts, you know, any secret boyfriends, that sort of thing. And a press strategy is usually discussed because appeals for information in the media can be very useful in these situations. Pip: So, if it’s a seventeen-year-old girl who’s gone missing, the police would have contacted her friends and boyfriend quite early on? Angela: Yes of course. Enquiries will be made because, if the missing person has run away, they are likely to be hiding out with a person close to them. Pip: And at what point in a missing persons case do police accept they are looking for a body? Angela: Well, timewise, it’s not . . . Oh, Pippa, I have to go. Sorry, I’ve been called into my meeting. Pip: Oh, OK, thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me. Angela: And if you have any more questions, just pop me an email and I’ll get to them when I can. Pip: Will do, thanks again. Angela: Bye.I found these statistics online:

80% of missing people are found in the first 24 hours. 97% are found in the first week. 99% of cases are resolved in the first year. That leaves just 1%.

1% of people who disappear are never found. But there’s another figure to consider: just 0.25% of all missing person cases have a fatal outcome.5

And where does this leave Andie Bell? Floating incessantly somewhere between 1% and 0.25%, fractionally increasing and decreasing in tiny decimal breaths.

But by now, most people accept that she’s dead, even though her body has never been recovered. And why is that?

Sal Singh is why.

Two

Pip’s hands strayed from the keyboard, her index fingers hovering over the w and h as she strained to listen to the commotion downstairs. A crash, heavy footsteps, skidding claws and unrestrained boyish giggles. In the next second it all became clear.

‘Joshua! Why is the dog wearing one of my shirts?!’ came Victor’s buoyant shout, the sound floating up through Pip’s carpet.

Pip snort-laughed as she clicked save on her production log and closed the lid of her laptop. It was a time-honoured daily crescendo from the moment her dad returned from work. He was never quiet: his whispers could be heard across the room, his whooping knee-slap laugh so loud it actually made people flinch, and every year, without fail, Pip woke to the sound of him tiptoeing the upstairs corridor to deliver Santa stockings on Christmas Eve.

Her stepdad was the living adversary of subtlety.

Downstairs, Pip found the scene mid-production. Joshua was running from room to room – from the kitchen to the hallway and into the living room – on repeat, cackling as he went.

Close behind was Barney, the golden retriever, wearing Pip’s dad’s loudest shirt: the blindingly green patterned one he’d bought during their last trip to Nigeria. The dog skidded elatedly across the polished oak in the hall, excitement whistling through his teeth.

And bringing up the rear was Victor in his grey Hugo Boss three-piece suit, charging all six and a half feet of himself after the dog and the boy, his laugh in wild climbing scale bursts. Their very own Amobi home-made Scooby-Doo montage.