Полная версия

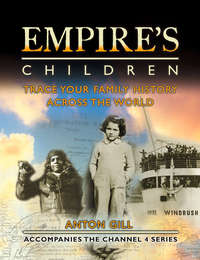

Empire’s Children: Trace Your Family History Across the World

We have – hopefully – come a long way since then. Most people, wherever they have come from, just want to get on with their lives, look after their families, have a more-or-less congenial job, and so on. That is self-evident. It is the few who muck things up for the many, and the many either have to put up with it or suffer. The people of Iraq, who as I write suffer outrages like the London bombs on a daily basis, are no different from anyone else in that respect. Prejudice against foreigners is endemic but it is essentially rare, and it is the child of propaganda. Many Muslims are in as great danger of tarring us white ‘Christians’ with the same sort of brush that we can be in danger of tarring them with. (And we should also be aware that as early as 1995 the French secret service had invented a nickname – ‘Londonistan’ – for our capital, as a result of their suspicion that it was a breeding ground for terrorists operating in Algeria; our reputation not helped by an initially, no doubt commendably liberal, but perhaps ultimately ill-advised indulgence towards such extremists as Abu Hamza al-Masri.)

The victims of the bombs in London, as they would have been in any concentrated multi-ethnic community, were random ones. Several members of what we still call ethnic minorities, including Muslims, inevitably died alongside ‘native’ Britons – something the bombers must have known. The hospital doctors and nurses who looked after the injured counted many non-ethnic Britons in their number. There was little racist reaction: we were united in common shock, outrage and grief. Ironically the most naked prejudice today – often stirred up by sections of the press – is against immigrants from the former Soviet bloc. But there is no stopping the tide, or the constant fluidity of demographics. The British Empire aside, an article appeared in the Evening Standard on 13 November 2006 pointing out that one-third of Londoners today were born outside Britain. This is a good thing. We should not forget that immigration has essentially enriched the country, not threatened or impoverished it. We had better get used to it, and the good news is that, slowly but surely, we are. This is only fair, since the British are a mongrel race anyway – and it is arguably that which has given them their edge in the past.

Britain is, generally speaking, a tolerant nation, though racism in many forms still exists. A thirty-five-year-old black London cabbie recently told me that when he was doing ‘the Knowledge’ his examiners – mainly ex-policemen – would tell him to drive to such destinations as Black Boy Lane (N15) and Blackall Street (EC2). However, there are some positive signs. About a year ago, I was pleased, if not 100 per cent convinced, by the optimism of a British-born Pakistani friend, who has had her share of racial abuse, who told me that she felt she was now living in a country whose institutions had become much more liberal in the last decade or so. She is about forty, and it seems to me, half a generation older, that a growing familiarity with other cultures is leading to a greater sense of ease. Many people have a South Asian doctor. Almost all city-dwellers have a South Asian corner shop or newsagent, or have eaten at one time or another in an Indian or Chinese restaurant. London probably has the greatest choice of cuisines of any city in the world, and Birmingham certainly has among the very best Indian restaurants. Many of our sporting heroes and heroines, whether they are athletes, cricketers or footballers, are of South East Asian, African or Afro-Caribbean origin. The Afro-Caribbean contribution to popular music since the late 1940s has been nothing short of revolutionary. Famously, chicken tikka masala (devised with the British palate in mind) has supplanted fish and chips (originally a French concoction) as the ‘national dish’.

It is probably true to say that most people born since, say, the mid-1960s – people who are now middle-aged – have greater tolerance than their parents’ generation, and their children will hopefully be more tolerant still – on both sides. After all, a large number of people of African, Afro-Caribbean and South Asian stock living in Britain today were born here, the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Empire, and the flowers on the grave of that once mighty organization. And if it is depressing to reflect that the current leader of the British National Party was only born in 1959, it is also worth remembering that he was influenced in youth by his parents, and that the BNP has nothing like the clout of, for example, its Austrian or its French counterparts (the latter itself inexorably losing ground), and that Britain can at least be proud that it has never contained a political party of the extreme racist right which has had more than a derisory following, even in areas where ‘blacks’ now outnumber ‘whites’. When the BNP leader was recently (in November 2006) acquitted (by an all-white jury) of charges of racial incitement, the official reaction of the government was an undertaking to reexamine ‘race hate’ laws.

There are still spheres of official life in Britain that are tainted by institutional racism, but in other public areas our record is good. In the sixties and seventies, sitcoms such as Love Thy Neighbour and Till Death Us Do Part dealt uncomfortably with the existence of racism. Although written from an ostensibly liberal point of view, and aspiring to show as ridiculous the characters who exhibited racism, all too often it was the non-European immigrant characters who were the butts of the jokes, and an uneasy sympathy sometimes bolstered the unpleasant protagonists. Such shows now seem to belong to a different planet. British television has nurtured a number of Asian and Afro-Caribbean sitcoms and series – from Empire Road by Michael Abbensetts and broadcast in the late 1970s to Meera Syal’s The Kumars at No. 42 and Goodness Gracious Me. That television is almost painfully aware of its responsibility is borne out by an article by Mark Sweney in the Guardian of 9 November 2006, detailing the results of an investigation carried out by the Open University and the University of Manchester for the British Film Institute (entitled ‘Media Culture: The Social Organisation of Media Practices in Contemporary Britain’), which found that programmes such as Coronation Street, A Touch of Frost and Midsomer Murders have little appeal for members of the non-white ethnic minorities resident in Britain. It is a difficult gap to bridge, for portrayal of the predominantly white communities in the latter two programmes is still valid; oversen-sitivity to the sensibilities of ethnic minorities could be detrimental to harmony.

Britain has a good record too in the field of television journalism, at least in the area of news presentation, where, especially at the BBC and Channel 4, a large proportion of presenters in all fields belong to non-white ethnic minorities. This invites very favourable comparison with the situation in most other European countries. France, for example, has one black female newsreader on France 3, though ethnic minorities are better represented on the new twenty-four-hour news service. In politics and sport, Africans, Afro-Caribbeans and South Asians enjoy a high profile. This is not necessarily new. The first Asian MP, Dadabhai Naoroji, a Parsi, was Liberal Party MP for Finsbury Central for three years from 1892. Maharajah Kumar Sri Ranjitsinji Vibhaji made his cricketing debut for Sussex in 1895. Not that such men’s achievements were anything but unusual for decades to come; nor were either politics or sport untainted by racism. In the year Naoroji lost his seat, Sir Mancherjee Bhownaggree won Bethnal Green for the Conservatives. Bhownaggree, a Parsi lawyer, was far from radical. He supported British rule in India and earned the nickname ‘Bow-the-knee’ from his Indian opponents. But the MP he replaced, a trade unionist called Charles Howell, was indignant that he had been ‘kicked out by a black man, a stranger’. Seventy-three years later, the Conservative MP Enoch Powell distinguished himself by delivering perhaps the most racially inflammatory mainstream political speech of modern times.

In sport, as recently as 2004, the former player and manager Ron Atkinson, who twenty-six years earlier had distinguished himself by the pioneering introduction into his West Bromwich Albion team of three Afro-Caribbean players – Brendan Batson, Laurie Cunningham and Cyrille Regis – disgraced himself when commentating by describing the black French player Marcel Desailly as: ‘He’s what is known in some schools as a fucking lazy thick nigger.’ For all that this may have been an isolated event, such a lapse in public can no longer be tolerated and Atkinson lost his jobs at ITV and on the Guardian instantly. The athlete Linford Christie has pointed out that when he won races, the press described him as a British athlete; when he lost them, he was either an immigrant or a Jamaican.

Christie came to Britain aged seven. For his services to athletics he was awarded, and accepted, the OBE. Meera Syal, born here, accepted the MBE in 1997. But the poet Benjamin Zephaniah, also born here, turned his down in 2003, defying convention by doing so publicly, and giving as his reason that it, and its association with the Empire, recalled to him ‘thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised’. This sparked a discussion about whether the ‘Empire’ gongs should be dropped altogether, though this is unlikely to happen soon.

There is no doubt that elsewhere a dark ghost of Empire remains, exemplified recently by the trial, still ongoing as I write, of Thomas Cholmondeley, heir to the Delamere fortune. The Delameres are an aristocratic family who have farmed in Kenya since the 3rd Baron arrived there in 1903, and they own huge tracts of land, appropriated from the Masai, in the Rift Valley. Their name is associated with the Happy Valley set, which became notorious through the book and film of the same title White Mischief. They do not have a high tradition of tolerance with regard to native Kenyans.

In April 2005, game warden Samson Ole Sisina, aged forty-four, was killed by the then thity-seven-year-old Cholmondeley on the Delamere family’s ranch near Lake Naivasha. Sisina was armed, and dressed in plain clothes, as part of an undercover investigation into the illegal trade in bush meat. Cholmondeley maintained that he shot the warden through the neck, but in self-defence, believing him to be a robber. Local whites immediately said it was the result of police failure to tackle a spate of car-jackings, burglaries and murders. Cholmondeley was acquitted, but in 2006 he was arraigned again on the charge of shooting another black Kenyan dead. This time, Cholmondeley claims that he mistook Robert Njoya for a poacher.

Matters remain tense. Assistant Minister of State Stephen Taurus told mourners at Njoya’s funeral that ‘it is time for these white settlers who are killing our sons to be kicked out of the country’.

PART ONE ‘RULE BRITANNIA’

JAMES THOMPSON

CHAPTER ONE GOLD AND PLUNDER

Not only did it last far longer than any other in modern times, but at its height the British Empire was also the largest the world had ever seen.

THE EMPIRE REACHED ITS GREATEST EXTENT WHEN BRITAIN COMMANDED AROUND 500 MILLION PEOPLE

The British Empire reached its greatest extent, ironically some time after its decline had set in, in the wake of the First World War, when Britain commanded nearly 40 million square kilometres of the earth’s landmass and around 500 million people – about a quarter of the planet’s terrain and about a quarter of the world’s population at the time. Look at any world map published around the turn of the last century, and you will see a huge part of it marked in red, the colour of the Empire. Red stretches in a more-or-less unbroken swathe from the Yukon in the north-west to New Zealand in the south-east. When it is 6.00 a.m. in the extreme north-west of Canada, it is 2.00 p.m. in London and 3.00 a.m. the following day in Auckland. This great sweep of land, with its massive population, comprising scores of different nationalities and races and hundreds of different languages, was truly ‘the empire on which the sun never sets’.

That Empire is gone, but its legacy is immense, and its effects are still felt in almost every corner of the world. Sir Richard Turnbull, among the last governors of Tanganyika and of Aden, once cynically told my mother that the Empire would leave behind only two traces of its existence, the game of football and the expression ‘fuck off’. That is understating the case. To take one other frivolous example (and many would argue with my choice of that adjective immediately), the game of cricket, whose origins in England go back at least as far as the sixteenth century, is only played as a serious professional game in countries across the world which were once part of the Empire. In the case of the Caribbean island states, it is a game they have made their own and at which they famously trounced the mother country first as early as 1950. In more mundane areas, British approaches to civil and military administration, and law, have taken root and continued to develop in countries that were once ruled by Britain, their efficacy underpinned by the fact that, for all their faults, the British were able to run their Empire with relatively small numbers of soldiers and civil servants. Techniques of commerce and banking (adopted from the Dutch and the Italians) evolved in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have continued to influence international trade. And the greatest legacy of the Empire is the English language.

THIS GREAT SWEEP OF LAND WAS TRULY’ THE EMPIRE ON WHICH THE SUN NEVER SETS’.

But what was all this built on? What was the lynchpin for the English (and later the British) to acquire and maintain their Empire? The answer is sea power. With the development of aeroplanes during and after the First World War and rocketry during the Second, the importance of the Royal Navy and its strategic ports across the world declined. Though ships and submarines as missile carriers would still make their contribution, the new craft could stay at sea for long periods. In the case of the submarines their whereabouts could be kept totally secret. They had no need of the old bases. The Empire was originally founded on maritime dominance. When this became a less important factor in world politics, and when other countries began to overtake us industrially, economically and in the development of new military technology, the Empire became far less easy to maintain.

One of the first monarchs to encourage overseas exploration was the Portuguese King Henry, called ‘the Navigator’, under whose sponsorship Portugal took and colonized the Azores as early as 1439. Having a west-facing coastline it was logical that the first line of travel should be westwards, and Henry’s explorers were soon followed by others. The Portuguese were great seafarers, and their development of shipbuilding technology would be closely followed by the two other European seafaring nations.

Exploration in the name of enrichment and the extension of power was what motivated the early navigators. Spain was not slow to follow Portugal in setting forth across the Atlantic, commissioning the (probably) Genoese sailor Cristóbal Colón (Columbus). He made four voyages westwards between 1492 and 1504, making landfall in the Caribbean and on the coast of Central America.

The idea that the earth was a sphere, and not flat, was widely acknowledged, and had been for centuries. As early as the beginning of the Christian era the earth’s spherical shape was accepted by most educated people in the West. The early astronomer Ptolemy based his maps on the idea of a curved globe and also developed the systems of longitude and latitude. Although arguments in favour of a flat earth still persisted, the modern idea that people in the Middle Ages generally believed in it is actually a nineteenth-century confection. A land route to the east had been well established since antiquity, and the Ancient Egyptians were already importing lapis lazuli – a hugely expensive luxury – from Afghanistan. But the development and refinement of the ocean-going ship opened a world of new possibilities. Rumours of great wealth overseas, and of the legendary Christian kingdom of Prester John, fired the imaginations of kings and explorers alike. Soon after Colón’s voyages, the Spanish realized that the lands he discovered did not belong to Asia as had been expected (his aim had been to find a westward route to the Spice Islands) but to an entirely new continent; and the reports he brought back of it were promising.

Although the Portuguese Vasco da Gama established a passage around the coast of Africa and the Cape of Good Hope to reach the south-eastern tip of India at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the main thrust of exploration by sea concentrated on the faster westward route, the theory being that one would reach lands of great wealth ‘somewhere off the west coast of Ireland’. The rivalry between Portugal and Spain needed some formal regulation, and Pope Innocent VIII presided over the negotiations which led to the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. It declared that all the undiscovered world to the west of a north – south meridian established about 1,550 kilometres west of the Cape Verde Islands should be the domain of Spain, and all of it to the east should be Portugal’s. The line, about 39° 50’ West, was not rigidly respected, and Spain did not oppose Portugal’s westward expansion into Brazil, which is why Brazilians speak Portuguese and the rest of South America speaks Spanish, but a demarcation was established.

It was far from the last time Western European countries would loftily carve up the rest of the world by treaties and edicts with no reference either to the people who lived there, or, often, to each other. Possession was nine-tenths of the law, and native inhabitants, whom they quickly found relatively easy to crush, the more so since they had no gunpowder, were there to be exploited or evicted. The first explorer to show real sympathy for or interest in local peoples was William Dampier in the latter half of the seventeenth century. (He was quite a man: pirate turned explorer-zoologist-hydrographer, he identified, plotted and traced the trade winds and published a book on them which stayed in use until the 1930s. No wonder Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn invited him to dinner.) The first circumnavigation of the globe was accomplished between 1519 and 1522 by the ships of another Portuguese, Fernão de Magalhães (Magellan), though he himself died in the Philippines and so did not complete the voyage. A new route, though a perilous one, cutting through what is now called the Magellan Strait, in Tierra del Fuego just to the north of Cape Horn, was thus established, and a new ocean opened up, which Magalhães named Mare Pacifico – the Pacific Ocean – because of the apparent calmness of its surface. The impact of this discovery on human history (together with the stories Magalhães’s surviving crew brought back when they finally returned home) was probably the greatest since that of fire or the wheel.

THE SPANISH REALIZED THAT THE LANDS COLON DISCOVERED BELONGED TO AN ENTIRELY NEW CONTINENT, AND REPORTS WERE PROMISING.

Meanwhile England, the other emergent maritime power of the time, had not been slow to pick up on the activities of Portugal and Spain. King Henry VII engaged another Genoese (some say he was Venetian), Giovanni (also known as Zuan) Caboto, to undertake a westward-bound voyage of discovery on his behalf, famously giving him:

full and free authoritie, leave, and power, to sayle to all partes, countreys… of the East, of the West, and of the North, under our banners and ensignes, with five ships… and as many mariners or men as they will have in saide ships, upon their own proper costes and charges, to seeke out, discover, and finde, whatsoever iles, countreys, regions or provinces of the heathen and infideles, whatsoever they bee, and in what part of the world soever they be, whiche before this time have beene unknowen to all Christians.

John Cabot, as we call him, set off in 1497, after a false start the year before, and became perhaps the first European to set foot on Newfoundland since the semi-legendary Viking voyagers of about 500 years before (we only know for sure that Erik the Red reached Greenland, but he or his successors may have got further, and there is evidence to suggest it).

Henry had sent Cabot, hot on the heels of the Portuguese and the Spanish, in search of something more than a large northern offshore island – and Cabot himself had meant to make landfall further south. The myth of El Dorado did not become current until thirty years later or so, but people’s imaginations had been fired by the possibilities of great wealth in the brand new continent that they suspected lay beyond the coastline they had hit. Cabot, it later turned out, had discovered wealth of another kind: the most fecund stocks of codfish in the world. In any case, he claimed Newfoundland for England. She had a foothold.

Henry VII was an extremely shrewd, financially alert monarch, and quick to realize that an investment in sea power would be a wise one. He accordingly started to build up his navy, a task which his son, Henry VIII, who succeeded him in 1509, took over with enthusiasm.

During the first half of the sixteenth century the Spanish developed colonies in the Caribbean, conquered Mexico, and began to make inroads into the continent of South America. Spanish galleons soon began to bring back gold and other treasures from the New World, and King Carlos V became a rich man, aiming at world power. At the same time, Henry VIII instituted the English Reformation and withdrew from the Roman Catholic Church. Envious of Spanish success, and also worried by the threat of overweening Spanish power, the English now began to see themselves as the potential champions of a Protestant Europe.

ENGLAND HAD BEEN GROWING EVER MORE CONFIDENT AS A NAVAL POWER AND THERE CAME A FLOWERING OF BRILLIANT ENGLISH SEAFARERS.

This ambition was checked by Henry’s ultra-Catholic daughter, Mary, whose reign saw England in danger of becoming a vassal of Spain, and it was not until Queen Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558 that the Church of England finally became properly established.

During this time, however, England had been growing ever more confident as a naval power and in response, perhaps by one of those accidents of history, perhaps because so great an opportunity was there, came a flowering of brilliant English seafarers. Many of them – and the politicians who backed them – were also staunchly anti-Catholic and anti-Spain. Elizabeth had no desire to see Spain remain in the ascendant unchallenged, but she had inherited a weak exchequer. In order to fill her coffers and undermine Spanish power, she condoned, semi-officially, what amounted to a campaign of piracy. If Spain had stolen a march on England and colonized lands which were a source of gold, then England would take her gold from her when and where she could. The propagandist and chronicler for all this activity was Richard Hakluyt, whose Voyages remain essential reading for any serious student of this period. And pirates did not only take gold. Where they could, they relieved the Spanish of their charts, which were worth more, since they traced coastlines and showed harbours, which the English had no knowledge of.

It was not simple piracy, of course – only Spain was officially targeted – and the men who carried out the campaigns ranged from bold adventurers and explorers like Sir Francis Drake, through Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Sir John Hawkins, to the cultivated and sophisticated Sir Walter Ralegh, whose last disastrous venture to South America in search of Eldorado, for the unpleasant King James I, was to cost him his life, as a sop to the King of Spain. In the course of his adventures, Drake became one of the earliest circumnavigators of the globe (1577–80) and the first to complete the voyage as commander of his own expedition from start to finish. Hawkins contributed many technical improvements to warships, and is now credited with introducing both tobacco and the potato to England. On a less noble note, he was also the first English mariner to become involved in the nascent slave trade. Ralegh founded the first British colony in North America on Roanoke Island, just off the coast of what was then the putative colony of Virginia (named in honour of Elizabeth, who had granted Ralegh a charter to claim land in the New World in her name). It was not a success at first, but it established what would become a permanent British settlement in the Americas. However, for all their efforts, the English never did find gold of their own in the Americas. Even the potato did not become popular for two centuries, though tobacco did. It was the first money-making product to come to the Old World.