Полная версия

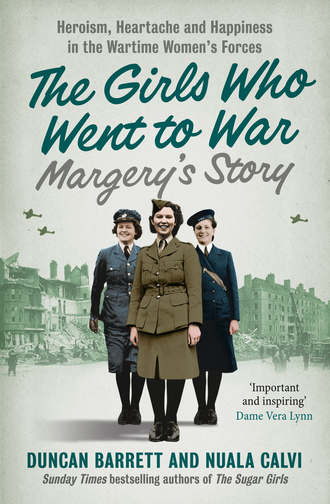

Margery’s Story: Heroism, heartache and happiness in the wartime women’s forces

Margery had arrived in Penarth expecting to train for pay accounts, but she soon found herself assigned to equipment accounts instead, along with about 60 other girls. It didn’t take long for her to learn the reason why – apparently the equipment accounts course was incredibly tough, and a large number of recruits who had recently attempted it had flunked out. The WAAF had decided to add an extra week of lessons for their replacements, in an attempt to improve the pitiful pass rate. But if Margery and her colleagues still failed to make the grade, they would be remustered and might end up in the kitchens or cleaning out the latrines after all.

Margery soon discovered for herself why the course was considered so difficult – it required a seemingly impossible feat of memory. There was a different form for every conceivable eventuality involving the issue of items in the Air Force, and the girls were expected to learn the official number of each of them. Form 674 was used to request a new item, but if the item in question was replacing an old and worn out one then a 673 was required instead. A 500 was needed for anything purchased from a private contractor, in which case a 531 would be required to issue the invoice, with the item ultimately paid for on a 600. The list of numbers seemed to be endless, and as well as memorising them all, the girls also had to learn how many copies of each form were required, and where each copy had to be sent. On top of that, every nut, bolt and screw, every piece of clothing, every item of food that went through the Air Force stores, had its own number as well, and these too had to be committed to memory.

Poor Margery had never been particularly good at rote learning, and her head was soon swimming. She worked diligently as ever, but the instructor was less than inspiring, simply reading out the information in a monotonous voice while the girls scribbled away frantically in their notebooks. After a few weeks, a sergeant was sent to check up on the class, and was horrified at their lack of progress. The instructor was promptly removed and a new one put in his place, but the sudden change didn’t exactly inspire confidence.

At least Margery’s days of living at Mrs Poole’s alone were over. One day she returned from her course to find a new arrival who had been billeted on the widow as well. She was a large girl with terrible bucked teeth, which she revealed in their full splendour as she greeted Margery with a big grin. ‘Oh, jolly good show,’ she said, holding out her hand. ‘I’m Oriole. Daddy named me after his ship.’

Margery had never felt like a pretty girl herself, but she couldn’t help feeling sorry for poor Oriole. Not only had she been lumbered with the name of a seafaring vessel, but she had a face that would struggle to launch a gravy boat, let alone a thousand ships.

With her clipped vowels and naval connections, Oriole seemed like the kind of girl who should have been in the WNRS rather than the WAAF. But Margery appreciated having someone to pass the time with before she was allowed to return to Mrs Poole’s for her evening meal. More than 150 miles away from her home in North Wallington, and with no older sister to look out for her, she had begun to feel terribly lonely.

It was Oriole who first introduced Margery to the delights of the local NAAFI – the Navy, Army and Air Force Institute. The NAAFI canteens and shops were becoming an increasingly familiar sight across Britain, offering forces personnel of the lower ranks a place to get cheap food and a hot drink. At last Margery had a place to go for a nice cup of tea once her classes finished, rather than traipsing along the seafront in the rain.

One day, Margery was sitting in the NAAFI with Oriole after a long and dreary afternoon in the classroom when an Army chap took a seat on the bench opposite them. As he warmed his hands over a steaming mug of coffee, he asked her, ‘Got any ciggie coupons, love?’

Margery looked up, startled. She and her friend didn’t usually attract the attention of the servicemen.

The man was a good ten years older than her, of medium build, with dark hair. There wasn’t much that was remarkable about him, except for a strong Lancashire accent, but he had a friendly face and that was something Margery was sorely missing.

‘I think I might have – hold on a minute,’ she said, rummaging in her pockets until she found her cigarette ration card. Since she didn’t smoke, she was happy to hand it over.

‘Don’t you want anything in return?’ the man asked, surprised.

‘Oh no, it’s all right,’ Margery told him.

‘Aw, go on,’ he pushed her. ‘How about a nice choccy coupon? That’d be a fair swap, wouldn’t it?’

Margery smiled shyly. ‘Yes, please,’ she said, taking the chocolate coupon gratefully.

The man seemed to interpret their little transaction as permission to stop and chat. Before long he had introduced himself as James Preston and was nattering away about the Army catering course he was doing in Penarth. He had an easy, Northern warmth, and Margery suspected that he, too, must be lonely and just keen to find someone to talk to while he was so far away from home.

Usually Margery kept on eye on the clock until 6 p.m. every evening, when she and Oriole were permitted to return home, so it came as a surprise when her friend pointed out that they were in danger of being late for dinner. ‘Better get moving, old thing,’ Oriole told her cheerfully. ‘Mrs Poole’s potato cakes wait for no woman!’

But before Oriole could drag her away from the NAAFI, Margery had agreed to meet James for coffee there the following day – and soon the afternoon chats had turned into a regular arrangement. For the first time since she had arrived in Penarth, Margery had begun to feel less cut adrift. All day long, as she studied the relentless lists of items and their numbers, she looked forward to the time she would be spending in the NAAFI with James.

With the end of Margery’s course looming, the need to study only increased, as she became more and more anxious that she might fail the dreaded test. Night after night, she went over the long list of forms and parts until her eyes were swimming with numbers. But the thought of having to write home and admit to her family that she had fallen at the first hurdle in the WAAF, and imagine them laughing at her ambitions again, was unbearable.

Finally, the dreaded day arrived, and Margery and the 60 other girls who had trained alongside her turned over their exam papers. She summoned all her brain power to the task of recalling as many of the wretched forms and parts as she could, as well as the various processes and procedures she had learned. But by the time she reached the final page of the exam, she had only been able to answer less than half of the questions.

The following day, the girls were ordered to line up in alphabetical order on the seafront. One by one, their surnames were called out, and their results were read off in front of everyone. Margery cringed as a good few of the As, Bs and Cs in the group were told that they had failed to reach even the remarkably low pass mark of 40 per cent. It was an agonising wait until the sergeant finally made it down to the letter P. ‘Pott,’ she barked, ‘40 per cent exactly. Pass.’

Margery blinked her eyes in the early morning sunlight. She couldn’t believe it – somehow, she had succeeded where so many others had failed. Despite her terrible memory and her crippling nerves, she had scraped through.

The poor girls who hadn’t been so lucky soon heard their fates. One of them was furious when she found out she was being sent to train as a cook. ‘I wanted to be in accounts!’ she cried miserably. But it was no use – once the Air Force had made up its mind, the decision was final.

Meanwhile, the girls who had passed the test were marched off for a series of inoculations. Feeling heady after her unexpected victory, and exhausted from the stress of the past few weeks, Margery fainted before she even saw the needle.

The next day, the girls were issued with railway warrants to take them home, so that they could spend a bit of time with their families before they had to report to their new postings. Margery was sorry to say goodbye to James Preston, but he had taken her service number and promised that he would write. The two months she had spent in the WAAF was the longest she had ever been away from home, and she felt desperate to get back to North Wallington again.

After a long train journey, Margery walked up the lane to the old maltster’s house, carrying her grey kitbag over her shoulders. The neighbours came out of their houses to get a look at her in her uniform, and when her parents opened the door she could see a glimmer of pride in their eyes.

Margery felt proud of herself too, she realised with a start. Nobody was laughing at her now.

Chapter 2

Having passed the dreaded test in equipment accounts, Margery waited anxiously for her posting to come through, wondering where on earth she would end up. By now, the Air Force had women working at stations the length and breadth of the land, from Cornwall to the Outer Hebrides. Some girls were serving as far afield as New York and Washington DC, while a small team of radio operators were about to set off for a post in Cairo.

But as it turned out, Margery’s new workplace was distinctly unexotic. She was ordered to report to RAF Titchfield, just four miles down the road from her home in North Wallington – so near, in fact, that she was expected to make her own way there, without any assistance from the Air Force.

It was a scorching summer’s day, and by the time Margery arrived at the camp, struggling under the weight of her heavy kitbag and clutching her respirator and helmet, her blue uniform was soaked with sweat and she was looking distinctly dishevelled. A guard on the gate glared at her before asking dismissively, ‘What are you, one of the new cooks?’

‘No,’ replied Margery, blushing. ‘I’m here for Equipment Accounts.’

When he heard the last word, the guard’s attitude seemed to change a little. ‘Name and number?’ he asked, slightly more civilly.

‘Pott, 294,’ replied Margery.

The man stared at her, a smile playing at the corners of his mouth. ‘Say that again, would you?’ he asked.

‘Pott, 294,’ she repeated.

The man turned to a fellow by his side and bellowed, ‘Sergeant, this woman is being rude to me!’ Then the two of them burst out laughing.

All her life, Margery had put up with jokes about her name, but the endless repetition hadn’t served to make it any easier. She wasn’t one to answer back, and in any case she wouldn’t dare to confront a guard, so she stood patiently, wiping the sweat from her brow, until finally the laughter died down.

The guard, whose face was by now as red as Margery’s, ushered her through the gate, and soon a WAAF sergeant came to collect her. ‘You can drop your kitbag in the dormitory hut,’ she told her, ‘and then I’ll show you to the office.’

Margery followed the other woman to a large wooden hut, similar to the one she had slept in during her initial training at Innsworth. There were 30 metal beds arranged along the two sides, with double lockers in between them. She left her things on an empty bed and then followed the WAAF sergeant back outside.

On her way to Equipment Accounts, Margery got her first proper look at the camp that was to be her home for the foreseeable future. It was a large site, where several hundred men and women worked side by side in seemingly endless rows of wooden huts. There were residential huts for the airmen and WAAFs who lived on the base, offices for administration and pay accounts, the camp police station and armoury, and a series of large mess buildings, with separate huts for officers, NCOs and other ranks. To Margery it seemed like an entire wooden city.

The Equipment Accounts office looked out over a wide parade ground, on the other side of which was the most striking feature of the camp: four giant aircraft hangars. RAF Titchfield was a maintenance station for Number 12 Balloon Centre, employed when the enormous inflatables, which were sent up from various sites in the area to disrupt low-flying German bombers, required repairs. In the vast hangars at Titchfield the fabric of the balloons would be checked for tears and stitched up by WAAFs handy with a sewing machine, before they were painted with three coats of silver ‘dope’ to prevent any hydrogen gas from leaking out. The girls charged with this unpleasant task spent their days inhaling the noxious fumes from the paint, and were given a special ration of milk as compensation.

The camp was also a training site for balloon-operating teams, and in a field off to one side Margery could see one of the huge inflatables being filled with gas. Lying on its side on the grass, it looked like a giant beached whale, but as Margery watched, the crumpled surface began to ripple and grow taut, until the magnificent 60-foot balloon slowly started to rise off the ground.

Although girls had been hard at work maintaining the balloons since the Battle of Britain, it was only recently that the WAAF had agreed to try out all-female teams to actually fly them. These ‘Young Amazons’, as they were known unofficially, were chosen for their physical strength – their training involved weight-lifting, as well as mastering the inflation procedure, splicing the ropes that held the balloons down and operating the winches that kept them anchored. The girls worked in teams of 12, whereas it was seven for all-male groups, but it was a tough job and many women ended up hospitalised with ruptured stomachs.

Compared to the work of the balloon girls, Margery’s job in Equipment Accounts was pretty low-risk, and the heaviest lifting she would have to do was heaving ledgers around the office. But that didn’t make her feel any less nervous as the WAAF sergeant led her up to the door.

She entered to find half a dozen young women, along with a handful of men, nattering away at their desks almost as if they were in a mess hall, not an office. For a moment, Margery was a little taken aback. This wasn’t the strict Air Force atmosphere she had grown used to during her training.

A male flight sergeant stood up and approached her. He was an ugly-looking fellow in his mid-thirties, tall and thin with dark hair. ‘Oh, you must be the girl from the course,’ he sneered. ‘I suppose you’re here to show us all how it’s done.’

Margery didn’t quite know how to respond to that. She nodded awkwardly and allowed herself to be led over to an empty desk, where she began familiarising herself with the ledgers she would be working on.

The job of Equipment Accounts was to keep track of things ordered from the camp stores – everything from cups and saucers to guns and ammunition. But it wasn’t long before Margery realised that her new colleagues had very little understanding of the procedures they were meant to follow. Since none of them had gone through the official training course, they had got used to muddling through with a mixture of common sense and improvisation.

Each item ordered at Titchfield would be registered on a form and signed by the officer responsible, but as Margery flicked through the paperwork, she began to notice a number of strange irregularities. Many of the forms in her ledger had been marked up with unfamiliar acronyms, ‘NIV’ and ‘OI’. Had she missed something in her accounts training, she wondered.

Nervously, Margery went up to the flight sergeant’s desk. ‘What do the letters NIV mean?’ she asked him.

‘Not in vocab,’ the man replied dismissively.

Margery was puzzled. She knew that every item, even down to the tiniest nut or screw, had a vocab number, which was supposed to be used on all paperwork. The idea of an item not being in vocab went against everything she had learned during her training. ‘What about OI?’ she asked, anxiously.

‘Over-issued,’ replied the flight sergeant, without looking up from his own work.

Now Margery was really confused. ‘I don’t understand,’ she told him. ‘How can you issue something you haven’t got?’

The man fidgeted in his chair, before mumbling, ‘Well … you know … it doesn’t really matter.’

His reply only made Margery feel more worried. Clearly something had gone badly wrong in Equipment Accounts. If they were audited, she realised, they could all find themselves in hot water. ‘Would you like me to go over to the stores and try to sort it out?’ Margery suggested helpfully.

But her boss was less than appreciative of the offer. ‘Suit yourself’ was all he said.

The girls in the stores were not much more interested in Margery’s problem than the flight sergeant had been, but after a bit of pleading, she persuaded them to consult their own records. It didn’t take long for her to work out where the irregular entries were coming from – if someone took a form down to the equipment store and hadn’t bothered to look up the vocab number, they would write ‘NIV’ in its place. The ‘OI’ was a way of covering their backs – as without the correct number, stock in the stores would no longer match up with what was written in the ledgers.

Back in the office, Margery didn’t say anything, but she was secretly horrified at the state of the department’s paperwork. From then on she made it her mission to put everything in order, beavering away at the ledgers and heading down to the stores every time she found an ‘NIV’, and begging the girls there to look it up for her.

The warrant officer who presided over the stores, however, was none too happy with someone from Accounts coming in and asking inconvenient questions. Around Titchfield, he was known as a bit of a bully, who delighted in tormenting new recruits, especially female ones. One day, when he saw Margery come into his department for the umpteenth time that week, he bellowed across the room, ‘Not you again, Pott!’

After her days working at the baker’s, under the reign of the terrifying Miss Pratt, Margery was used to putting up with rough treatment from those in authority. But right now her heart swelled against it. After all, she was the one striving to put the books in order, despite the lackadaisical attitude of her colleagues. To bawl her out publicly just for making a bit of an effort seemed so unfair.

‘Who does that man think he is?’ Margery muttered to a girl standing next to her.

The words had slipped out before she could stop herself, but she realised, to her horror, that the warrant officer had heard them. ‘What was that?’ he demanded, striding over and fixing her with an angry stare.

Margery gulped – but there was no going back now. ‘I said, “Who does that man think he is?”’ she replied, before adding, ‘Sir.’

She could hardly believe that she had done it. Ordinarily, Margery wouldn’t say boo to a goose – she was the last person to stand up to authority.

Suddenly the implications of her uncharacteristic outburst began to dawn on her. She was for it now, she felt certain – her career in the WAAF was about to come to an ignominious end with a court-martial for insubordination.

But to Margery’s surprise, instead of yelling at her, the warrant officer burst out laughing, evidently tickled pink at her unexpected forthrightness and honesty. ‘I like it when one of the girls shows a bit of gumption,’ he told her, once he had caught his breath. ‘It doesn’t happen to me all that often.’

Margery was stunned at the sudden change in the man’s attitude. But she was beginning to feel a little more confident now, so she asked him boldly, ‘Why do you talk to people like that?’

The man thought for a moment, and then gave a rueful smile. ‘Well,’ he admitted, ‘I suppose I like seeing them quake.’ Then he turned around, still laughing, and went on his way.

After that, Margery never had any trouble from the warrant officer again. When she saw him in the stores he was always courteous, and sometimes even downright friendly. She certainly hadn’t gone down there looking to assert herself, but in doing so she had learned a valuable lesson: sometimes, if you stood up for yourself, people respected you more.

While Equipment Accounts was not exactly a beacon of high standards, everywhere else around RAF Titchfield things were run very much by the book. Unlike Penarth, where Margery had been free to wander along the sea front for hours at a time, here she was truly subjected to the rigours of Air Force discipline. There were regular parades, drills and route marches, and every day the camp flag was raised and lowered in military style.

The airwomen’s days began at 7 a.m., when a corporal yelled through the door of their hut, letting them know that it was time for physical training. After they had run around the camp a few times in just their shorts and shirt tops, beds had to be stripped and stacked to exacting specifications. Only then were the girls lined up in flights and marched off to breakfast.

Once they’d eaten, the half-dozen young women in Equipment Accounts would form another flight to march over to the office, even though it was just the other side of the parade ground. The rigorous military discipline continued throughout the day – the lax atmosphere within the office itself excepted – until the dormitory lights were switched out by the duty corporal at 10.30 p.m. sharp.

As the months rolled by and the weather turned colder, nights spent in the wooden dorm huts, where one window was always left open, whatever the weather, grew increasingly miserable. And it wasn’t much warmer in Equipment Accounts either. When the flight sergeant saw the girls shivering at their desks, his solution was to order them to take their tunics off, roll up their sleeves and run around the camp. The girls certainly returned warmed up – but also dripping with sweat, which they struggled to keep from blotting their ledgers.

The huts were not only cold but dark as well, and the dwindling daylight hours made it increasingly hard for the girls to read the paperwork in front of them. They complained bitterly to each other and encouraged Margery, who as ‘the girl from the course’ carried a certain dubious authority, to mention the problem to a WAAF officer on their behalf. But to Margery’s dismay, when the unimpressed officer turned up at the hut and demanded to know if anyone else felt the same way as she did, suddenly the cat seemed to have got her colleagues’ tongues. Margery was carted off in an ambulance to get her eyes tested at the nearest hospital, returning with a very ugly pair of steel spectacles. They were distance glasses, so they made no difference to her work in the dimly lit office, but the sight of her wearing them gave the rest of the girls a good laugh.

One thing that brightened Margery’s days at Titchfield was the arrival of the latest letter from James Preston, the Army cook from Lancashire who she had met during her training in Penarth. He had recently been posted to a camp on the Isle of Dogs in London, and for Margery his long, artfully written letters brought every detail of his experiences there to life. Tearing open the latest missive to find page upon page of his beautiful handwriting always brought a smile to her face.

It was James who had helped allay Margery’s loneliness during her time in Wales, but at Titchfield she made her first proper friend in the WAAF – a Geordie woman in her mid-thirties called May Strong, who more than lived up to her name. May was the corporal in charge of Margery’s dorm hut, and slept in a private room at one end of it. Before the war, she had worked as an office manager at a paint factory in Haltwhistle, a coal-mining town not far from Newcastle. She had a natural self-assurance and authority, combined with a talent for leadership, and all the girls in the hut looked up to her – none of them more so than Margery.

One evening, when one of Margery’s hut-mates was suffering with a bad cold, May announced that she knew just what to do. ‘A tot of whisky would cure this,’ she proclaimed. Then turning to Margery, she said, ‘Come on, we can get some at the Joseph Paxton.’

It wasn’t exactly an order, but somehow Margery didn’t feel she could say no, so she grabbed an empty bottle and accompanied May to the pub in the nearby town of Locks Heath.