Полная версия

Constance Street: The true story of one family and one street in London’s East End

Copyright

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Charlie Connelly 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Topfoto (two women); John Topham/Topfoto (background)

(The people in the images are in no way related to any of the people portrayed in this book)

Charlie Connelly asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780007528455

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780007528448

Version: 2015-07-09

By the Same Author

And Did Those Feet

Attention All Shipping

Bring Me Sunshine

The Forgotten Soldier

London Fields

Many Miles

Our Man in Hibernia

In Search of Elvis

Spirit High and Passion Pure

Stamping Grounds

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

By the Same Author

Dedication

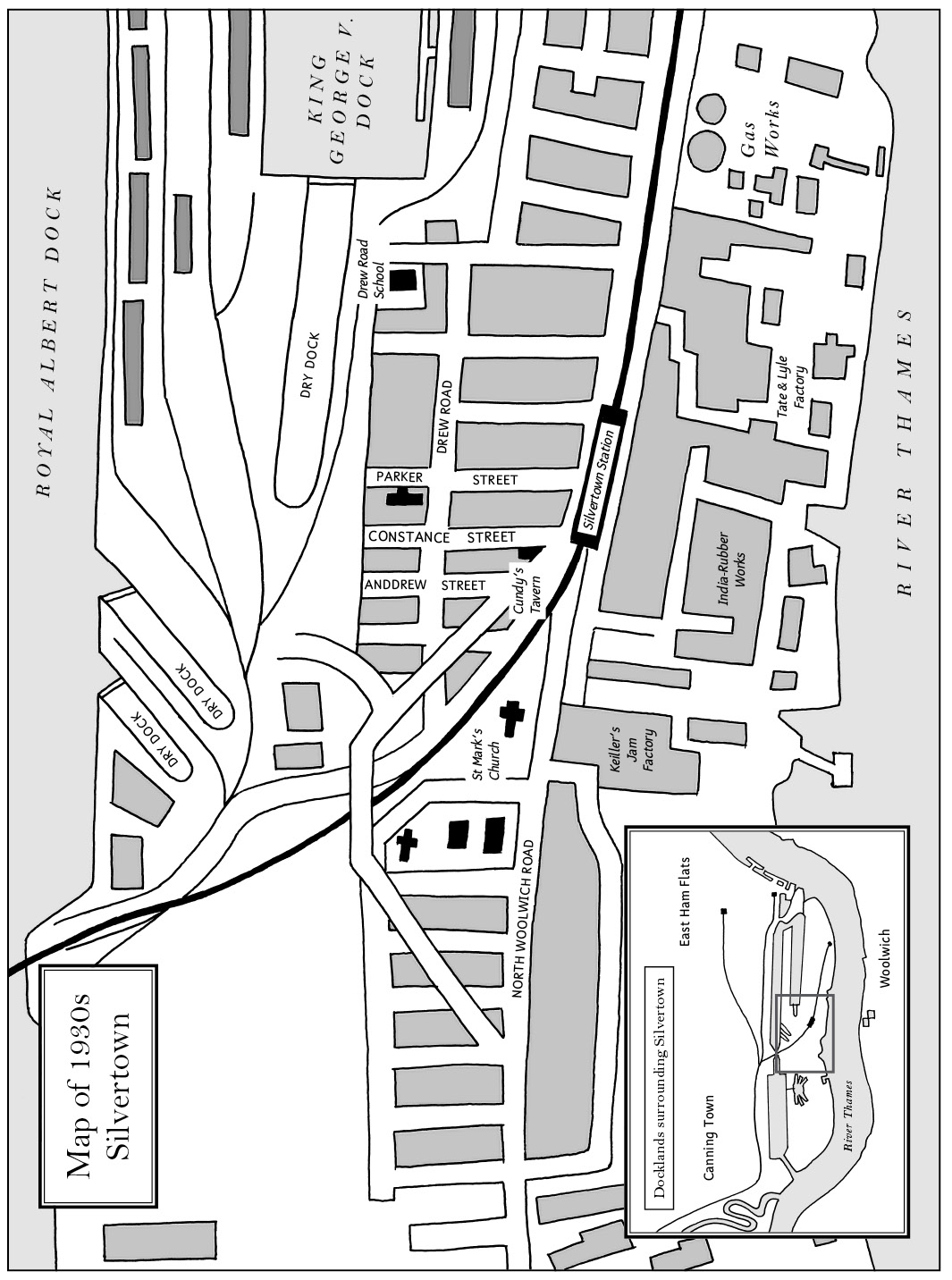

Map

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Acknowledgements

Exclusive sample chapter

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Write for Us

About the Publisher

Dedication

For my mum, Valerie Connelly, the last Greenwood Silvertonian, and in memory of Joan Thunstrom, née Greenwood, 1923– 2015

Chapter One

A little before seven o’clock on the evening of 19 January 1917, Nellie Greenwood was just about to close up the laundry when all the windows blew in.

Just before it happened the lamps had flickered for a couple of seconds, causing her to look up with the heavy iron poised just above the sheet she was pressing. There was a brilliant flash, a second for the breath to catch in her throat, then a whump, a deafening roar, a blizzard of shards and a screeching ring in her ears. She clamped her eyes closed and, as the ringing diminished, other sounds began to emerge from the white noise: a metal lid spinning to a halt on the floor nearby, the Christmas tinkle of the last slivers of falling glass, the bang of a window frame flapping open, all as if it were a very long way away.

Then silence, and the chill seeping into her cheek that told her she was lying on the stone floor.

Tendrils of cold began to seep through the broken windows and open door and settle around her. Silvertown was never silent, not ever, which despite the screaming noise inside her own head made the sudden absence of the clanking of dock cranes and the distant shrieking of the sawmill even more curious. As Nellie slowly began to regain her senses she realised there was something else nagging at her; something about the silence inside 15 Constance Street was wrong.

A week earlier her husband Harry had wheeled her around this very floor, dancing to a hummed tune of his own devising to mark her thirty-ninth birthday. He’d managed to coax her out to Cundy’s, the pub at the end of the street, for a couple of hours in the evening, leaving their eldest child Winifred in charge of her five younger sisters, and when Nell insisted on checking whether she’d left the float in the till when they’d returned from the pub, he’d pushed his cap back on his head, grabbed her waist with one hand and her hand with the other and whisked her in circles.

‘Forty next year, doll,’ he said between hums, his breath sharp with the tang of alcohol. ‘Who’d have thought we’d live so long, eh? And you not looking a day older than the first time I clapped eyes on you.’

She told him to get away with himself. In the mirror that morning she’d noticed more grey streaks in her brown hair as well as the lines spreading from the corners of her eyes and heading due south from the corners of her mouth to her jaw line. She’d run her fingertip down them, her hands permanently pink and shiny from years of washing and scrubbing, from domestic laundry as a girl to running her own laundry today.

Thirty-nine, she’d thought, and I’m looking and feeling every day of it. And me with a four-month-old baby, too.

A four-month-old baby.

Nell scrambled to her feet, kicking away the drying frame that had fallen across her legs, and stood bolt upright, blinking, glass falling from her pinafore and her green floral dress. She ran for the stairs, taking them two at a time. The door to the back bedroom had slammed shut: Nellie shouldered it open and half stumbled, half fell into the room. There was broken glass everywhere, the washstand had blown over, the basin was smashed, the little framed pictures were off the walls, and in the corner was the crib, tipped onto its side and sprinkled with sharp slivers that twinkled in the twilight like birthday icing. Next to the upturned crib, face down and sprawled motionless on the floor among the daggers of glass, four-month-old Rose.

Fighting back a sudden surge of cold nausea, Nellie took two long paces forward, each seeming as if there were suddenly miles between her and her child. She reached down with her raw, laundress’s hands and carefully picked the baby off the ground. She was limp. She turned the child around and held her face to face. Rose stirred, stretched her arms, fanned her fingers, yawned and half opened an eye.

Nellie pulled the baby into her shoulder and allowed a tear of relief to fall. She brushed a couple of glass fragments from the back of Rose’s nightdress and finally allowed herself to exhale, bouncing the child back to sleep on her shoulder. Into the room ran two of her daughters, Annie and Ivy. Their eyes were wide with shock, they were blinking back tears and mouthing words at her, but she could hear nothing except the tuneless high-pitched music inside her head, like the constant jostling tinkle of a thousand needles. It was only when she noticed how their shadows on the wall were a sharp silhouette against an eerie, glowing orange did Nellie begin to speculate about what might have just happened. She turned to face the window and saw the horizon fiery red over West Silvertown. The sun had set more than an hour ago, yet the sky burned orange as if it was rising again in the west.

She made a rapid mental roll-call of daughters. Annie, Ivy and Rose were here. Kit was with Win, delivering some laundry to North Woolwich. That was farther east, they’d probably be all right. Harry was at the docks collecting some table linen from one of the liners. It was the Albert Dock, so again, farther away from here, he’d be all right too, she reasoned with herself. That left Norah; she had been helping with something at the school a couple of streets away. Drew Road School was a big, solid building. Norah was probably all right. Please, she thought, let all of them be all right.

Through the jangling needles she began to hear crying – Ivy and Annie, 10 and 11 respectively, were at her side, tears streaming down their cheeks. She longed to embrace them but she was still carrying Rose. She nodded at the crib and Annie went over and set it upright. Ivy took the blanket to the broken window and flicked it out a few times before examining it closely for stray shards while Annie ran her hands around the inside of the crib. There didn’t seem to be any glass inside it and, once satisfied it was safe, Nell laid Rose, still sleeping, in the crib, tucked the blankets around her, dropped to her haunches and pulled her older daughters to her, their faces at her breast, and kissed the tops of their heads. The scene was still lit by the malevolent, flickering orange glow from the west that was bathing the room in a curiously soothing light.

‘Nell!’

The cry came from downstairs and she heard frantic footsteps on the broken glass inside the doorway.

‘Up here, Harry.’

The footsteps bounded up the stairs and her husband hurtled into the room, his piercing blue eyes flashing with concern.

‘Are you all right? Are the girls all right?’

‘We’re all right here, I think, yes. Kit and Win are at North Woolwich and Norah’s at the school. What is it? A bombing raid?’

‘Don’t know,’ he replied. ‘I was just on my way back from the Albert, just left the dock gate, when there was this flash in the sky and the next thing I know something’s knocked me off my feet and I’m in the gutter and everyone’s on the ground. I’ve got up and run all the way home. There’s not a window left between here and the docks.’

He thought for a moment.

‘If it’s a bomb, it’s one hell of a bomb.’

‘Stay with the girls, Harry,’ she said, rising to her feet again, ‘and wait here with them. Rose is asleep in the crib. Take them all into the parlour and get a fire going, it’s bloody freezing in here. I’m going round the school to find Norah. I wouldn’t think the trains will be running now so Win and Kit will be walking back and I want someone here when they arrive.’

‘OK, doll,’ he said.‘Try not to worry,’ he added. ‘They’re sensible kids, I’m sure they’re all fine.’

Nellie walked down the stairs, crunched across the broken glass and opened the shop door onto Constance Street. Beneath the fiery twilight the street was dark: the gas lamps had all shattered and blown out. She looked south towards the junction with Connaught Road and the Thames-side factories beyond, and in the gloom saw the silhouettes of men running, some in the direction of the glow, others going the other way. Somewhere, faintly, she heard a woman screaming. White faces loomed in the doorways and windows in the street. Drinkers in Cundy’s had gathered outside – people she knew, Constance Street people. Nellie set off north, though, towards the junction with Drew Road, and just as she got there was nearly knocked clean off her feet as Norah came racing round the corner.

‘Norah, love, are you all right?’

‘Mum! Yes, I’m all right,’ panted the eight-year-old. ‘We were putting away some tables and chairs and suddenly all the windows broke! They sent us home.’

She took Norah’s hand and walked down Constance Street, the way strewn with glass and debris. Each of the half-dozen or so shop-fronts she passed was dark, each window reduced to jagged fragments. On the other side of the street, curtains flapped hesitantly through the broken windows, tugged outside by the chill breeze. Nell paused briefly at some of the gaping shops as she passed, making sure everyone was all right inside, but nobody seemed to know what had happened, just the bright flash, then the pause and then all the windows blowing in.

At the end of the street, opposite the station, a crowd had gathered outside Cundy’s. Still holding Norah’s hand, she joined the group. There was Frank Levitt, the butcher whose shop was next door to the pub. He still wore his butcher’s apron and hat.

‘What is it, Frank?’ she asked. ‘What’s happened?’

He looked at her, his face almost as pale as his apron.

‘You’re cut, Nell,’ he said.

Nellie felt a warm trickle from her right temple, just behind the hairline. She caught it with a forefinger. It wasn’t a serious wound, but she noticed cuts on the backs of her hands too.

‘It’s nothing,’ she said, ‘I’m all right. What’s happened? Are we bombed?’

She thought back to the night a year or so earlier when she’d seen the Zeppelin over Bow, slow and stately, and remembered the elegance of the searchlight beams playing around it, the low and distant hum that she’d felt faintly in her chest, the bright shell-bursts puffing around the giant airship, then the low horizon flashes and the sickening distant thud of bombs dropping. She’d wondered how such beauty could be seen in such a fearful thing.

But this was different, surely. She’d heard no Zeppelin, no hum in the sky, not even the throaty rasp of the Gotha planes they’d begun to use on bombing raids. She looked along Connaught Road towards the glow in the west and saw more shocked people beginning to emerge from their violated homes and businesses. The glow was a good half-mile away, yet there was utter devastation here. This was more damage than a whole squadron of Zeppelins could ever do.

‘We’re not bombed, Nell,’ said Simeon Cundy, the landlord of the pub. ‘It can’t be a bomb. Too big. There ain’t a bomb in the world that could do this.’

‘Unless there’s a new bomb,’ said another voice, ‘a big one, bigger than anything we’ve seen.’

‘Or mines,’ said another, ‘if the Hun has put a mine in the river and a ship’s gone up …’

‘A factory,’ said another man, incredulously. ‘I reckon it must be one of the factories blown up. Gawd bless the poor souls down there anyway.’

A smell of burning grew stronger until it began to irritate their eyes and nostrils, then a dark cloud of thick smoke came billowing through the sky and along the street towards them. The group stood back against the wall of Cundy’s as it drifted past along Connaught Road and over the roofs of Constance Street, darkening everything beneath the fiery twilight. No one spoke, they all stood in silence trying to process the enormity of what might have happened. Then Nellie heard coughing and a man emerged from the darkness. He was limping, his face was blackened and he had his left arm clamped to his side with his right. He was breathless and tired, as if he’d been running, and was shouting something in all directions.

‘Brunner Mond,’ he called in their direction, ‘Brunner Mond’s has blown up! Brunner Mond’s has blown up! It’s all gone!’

Nell’s shoulders drooped. Of course. It would be an exaggeration to say she’d seen it coming, but …

Brunner Mond, an already successful company based in Liverpool, had opened a chemical works at Crescent Wharf in West Silvertown in 1893. In the main factory they made soda crystals, while in the secondary plant on the site they manufactured caustic soda – but this had been discontinued a couple of years before war broke out. In September 1915 the government had requisitioned the old caustic soda works and turned them into a TNT purification plant in order to keep up with the demand for munitions at the front.

‘Silvertown is perfect!’ the deskbound map-pinners who make these kinds of decisions had said. ‘Ideally located and with a ready-made workforce to boot!’

The residents of Silvertown, while not openly dissenting, were uneasy; its saloon bars and back parlours murmuring with reservations through pursed lips about high explosives and packed streets of jerry-built houses. When they were preparing to open the plant, Harry had gone down there to see about some work but had come back shaking his head and sucking his teeth. ‘Don’t like the look of it, doll,’ he’d said to Nell. ‘They’re going to work all round the clock, shift work, means there’ll be constant deliveries of dangerous stuff day and night – there’s so much of it that trucks aren’t enough: they’re bringing it in on trains and barges as well. And they’re just moving in and starting straight away, when the place is set up for making caustic soda, not bombs. The people I spoke to down there seem out of their depth, to me. Got a bad feeling about it.’

Brunner Mond’s going up would make a warped kind of sense, thought Nell, as she began to notice strange golden speckles falling from the sky that danced in the air around them, billows of brilliant orange pinpricks that glowed and flared in the breeze and died wherever they landed. Jacob Eid, the baker, picked one from his jacket sleeve and examined the small black speck in the palm of his hand. He lifted it to his nose and sniffed it.

‘It’s wheat grain,’ he said, incredulously, holding it up between finger and thumb like a jeweller inspecting a precious stone. ‘This is wheat grain. Lord save us, don’t tell me the flour mill’s gone up too.’

The gathering at the corner of Constance Street fell silent and looked for a while at the western sky still burning bright orange as if the sun was clinging to the horizon and refusing to set. On the breeze rumbled the low, malicious thunder of distant flames. They all stood for a while, wordless, helpless, fearful, hands thrust into pockets and collars turned up against the cold, feeling occasional wafts of smoky warmth drifting across from the west.

And then they came. Out of the smoke, out of the glow, out of the darkness, among the billow of golden sparks: the people. A trickle at first, the advance party of the bewildered and the injured. A woman, wide-eyed in a torn coat, swivelling from side to side as she walked, shouting ‘Billy!’ at the buildings on one side of the street and then the other. A young man, deathly pale, his eyes dark and sunken, blood pouring down the left side of his face and neck, staining his jacket, glassy-eyed, looking ahead but looking at nothing, just walking, just getting away. A mother, hand in hand with two young children, all three of them blackened and shiny, repeated, at nobody in particular, ‘It’s gone. All of it. It’s all gone.’

Nellie watched them pass and saw more following behind, a shuffling stream of humanity, uncomprehending, mouths open, breath clouding in the chill evening, eyes seeing nothing, a parade of the shocked, a carnival of casualties. She leaned down to Norah and spoke directly into her ear.

‘Go home, Norah. I’ll be along in a minute.’

Once she’d watched her daughter run back along the street and turn into the doorway of the laundry, she looked back at those passing the end of Constance Street. It was like a parade of the damned. The wind changed, turned to the south and sent the clouds of smoke across the river, giving central Silvertown some relief from the oily smoke and brightening the streets a little, courtesy of the eerie orange glow.

Nell thought of baby Rose, a tiny pinprick of innocence among all this dread, while watching the shuffling procession pass by from a catastrophe whose scale those gathered at the corner of Constance Street could only guess at. She closed her eyes, and pictured bending her head to press her nose to Rose’s cap and breathing in a mixture of soap and baby. She became overwhelmed by a need to protect. The image of Rose, face down on the floor surrounded by glass and debris, came into her mind and made her shudder. These people, these wild-eyed, waxy-pale husks of humanity, they were all Rose to somebody. None of them deserved this. Whatever had happened over there, whatever horrors lay a few hundred yards to the west, had as far as she could deduce left these people with nothing. As well as their physical injuries they were all in a state of nervous shock, driven on by a base human instinct to get as far away from danger as possible. A wave of maternal compassion ran over her. These were her people, Silvertown people, yet they were suddenly otherworldly and vulnerable. She stepped into the street to a young man whose left arm was hanging at a sickening angle.

‘Here, boy,’ she said, and then, louder, ‘and anyone else, come with me,’ she called. ‘I’ve a laundry up this way. You can shelter there until …’ Until what? She wasn’t sure. ‘Tell you what, we’ll all have a nice cup of tea.’ She heard the words come out of her mouth and almost winced at the triteness of them, but this was the banality of disaster: normal was good, normal was what you needed at a time like this, and there’s nothing more normal than tea.

Thus Nellie Greenwood, businesswoman, wife and mother of ten, just embarked on her fortieth year, led a gaggle of the broken and bewildered along Constance Street to the battered and shattered business she ran with her husband with help from her daughters. She wasn’t entirely sure what she was going to do with them when she got there, but she knew that right now they needed her more than anything in the world.

Chapter Two

Nellie Greenwood was my great-grandmother and I never knew her. At least, I never knew her in the sense that she’d died before I was born. Such was her legacy, however, such the force of her personality and the mixture of affection and fear she’d instilled in those who grew up with and around her, that I’ve almost manufactured false memories of Nell of my own. So powerful was her character that photographs familiar from albums and mantelpieces move and talk in my mind.

Nell was ‘Gran’ to everyone, whatever their generation, the matriarch, the central node around whom all family business and life was conducted. A formidable working-class woman who’d forged a business from nothing, who’d worked hard all her life, asked for nothing and expected nothing, bore thirteen children of whom five didn’t survive to adulthood, while informally adopting at least one other, and who despite knowing hardship, frustration, tragedy and loss, and never being less than forthright, opinionated and frank, never lost the deep and innate kindness that underpinned her life.

It’s thanks to Nellie that Silvertown was, is, and will most likely continue to be, for another couple of generations at least, regarded as home by my mother’s family even though none of us has lived there for more than seventy-five years. Between the wars Nellie was the heart of the family and the heart of Constance Street, which in turn was the heart at the centre of Silvertown, a community in east London isolated between the docks and the river where Nellie and the rest of the Greenwoods allowed their roots to embed in the marshy earth. Silvertown is, as my grandmother would frequently remind me, an island – because of the docks you have to cross water to leave – and an island mentality developed there. A closeness of kin and a bond to a place that formed ties so tight it would take something spectacular to break them. The physical ties would indeed be broken in such a fashion, but the spiritual ones linger and show no sign of weakening any time soon. ‘You’ve got dock water in your veins, boy,’ my grandmother Rose would tell me, ‘and don’t you forget it.’