Полная версия

The Roman Republic

The war was settled by Roman persistence, a characteristic which had already helped to defeat Pyrrhus and which was to help defeat Hannibal, the chief Carthaginian general in the Second Punic War; Rome built one more fleet than Carthage was capable of building and in the peace imposed in 241 made Carthage withdraw from Sicily and pay a large indemnity. By a piece of what even Polybius regarded as sharp practice, Rome acquired Sardinia and Corsica shortly after.

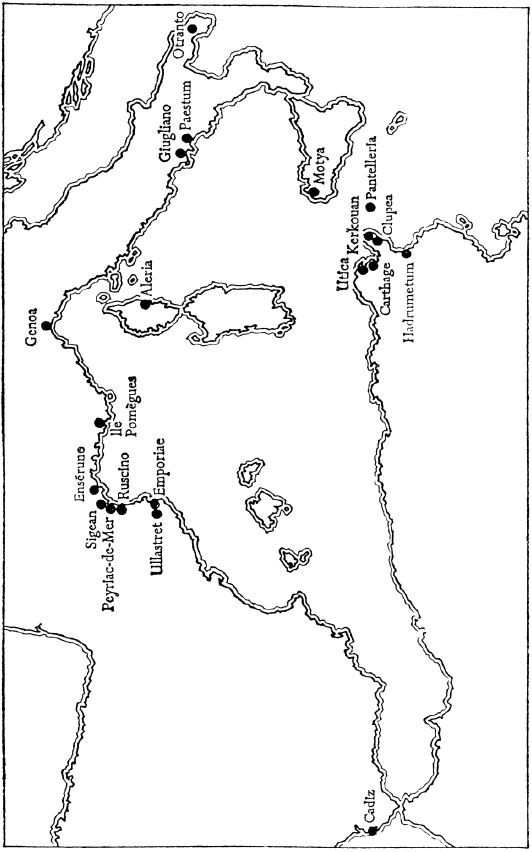

Not altogether surprisingly, there were those in Carthage who did not regard the verdict of the First Punic War as final; the creation of an empire in Spain and the acquisition thereby of substantial military and financial resources were followed by Hannibal’s invasion of Italy in 218 (the Roman tradition attempted to make the entirely justified attack on Saguntum by Hannibal into the casus belli, in order to salve its conscience over the failure to respond effectively to the appeal by Saguntum to Rome, see here). By a curious irony, the decisive confrontation between Rome and Carthage came at a moment when trading links between the two communities were greater than ever before – a large part of such fine pottery as Rome exported in the third quarter of the third century went to Carthage and her neighbourhood.2

Hannibal’s initial success was electrifying; invading Italy with 20,000 infantry and 6000 cavalry, he defeated the Romans in a succession of battles; at the River Ticinus and the River Trebia in the Po valley in 218, at Lake Trasimene in Etruria in 217 and at Cannae in south-east Italy in 216. Given his small forces, it was inevitable that he should seek to supplement them with such allies as became available and indeed ultimate success depended on detaching the majority of the members of the Roman confederacy. Given the secular enmity between the Romans and the Gauls settled in the Po valley and the Roman attempts immediately before 218 to plant colonies in the Po valley, it was inevitable that the Gauls should be anxious to join him, quite apart from the prospects of plunder. Their adhesion, however, was unlikely to endear Hannibal to the rest of Italy.

5 Map showing places to which Roman fine pottery was exported in the middle of the third century BC

Hannibal’s spectacular initial successes in fact only masked a deeper long-term failure. The battle of Cannae was followed by the revolt of a number of Italian communities and conspicuously of Capua, some eager to abandon Rome, others constrained to do so by military force; Hieronymus, the grandson of Rome’s ally of the First Punic War, Hiero of Syracuse (see here), was persuaded to join Carthage. But most of Rome’s allies remained loyal and the community of interest between them and Rome remained the most important factor in deciding the outcome of the war.

It was clear in the immediate aftermath of Cannae that Rome had no intention of ever surrendering; given that, her allies recalled her leadership in the series of battles against Gallic raids and the fact that the Gauls were now allied with Hannibal. They recalled the sense of identity which Rome had created for an Italy united under her leadership. Above all they recalled the shared rewards of success.

Syracuse was recaptured by M. Claudius Marcellus in 211, having held out so long only because of the ingenuity of the engines designed by Archimedes (who was killed in the sack). In 209 P. Cornelius Scipio captured the Carthaginian base in Spain, Nova Carthago. Meanwhile in Italy, Hannibal was forced to watch the superior manpower of an essentially unshaken Roman confederacy slowly subjugating the cities which he had won over and which he was unable to defend. In 207 he summoned Hasdrubal and the remaining Carthaginian forces from Spain, but they were destroyed in a battle beside the River Metaurus in north-east Italy. Hannibal’s departure from Italy and ultimate defeat in 202 at Zama by a Roman expeditionary force under P. Cornelius Scipio, as a result surnamed Africanus, were only a matter of time.

The measure of Rome’s control over her allies is her response to the plea in 209 of twelve of her Latin colonies that they could neither provide more men nor pay for them:

There were then thirty (Latin) colonies; twelve of these, when representatives of all were at Rome, informed the consuls that they no longer had the resources to provide men or money … Shocked to the core, the consuls hoped to frighten them out of such a disastrous state of mind and thought that they would get further by rebuke and reproof than by a gentle approach; so they claimed that the colonies had dared to tell the consuls what the consuls would not bring themselves to repeat in the senate; it was not a question of inability to bear the military burden, but open disloyalty to the Roman people … (The remaining colonies produced more than their quota; the delinquent colonies were temporarily ignored and later severely punished by the imposition of additional burdens.) (Livy XXVII, 9, 7)

Just as the rewards of success kept her confederacy loyal to Rome despite occasional rumblings, so they held the lower orders loyal to the rule of the oligarchy, again with occasional rumblings. The career of the novus homo, a man without ancestors who had held office, Manius Curius Dentatus, undoubtedly depended on popular support. Consul in 290, he defeated the Samnites and the Sabines, and celebrated two triumphs, and he then distributed land taken from the Sabines among the Roman needy. Not surprisingly he went on to hold command again, against a Gallic tribe, the Senones, in the 280s; he then held office yet again, to inflict defeat on Pyrrhus in 275. A final consulate in 274 was his reward.

But the most serious clash before the second century between the will of the oligarchy and a representative of the people was provoked by C. Flaminius, tribune in 232, who carried in that year against the opposition of the senate a law by which individual allotments were made to Roman citizens in the Ager Gallicus and Ager Picenus. The bitterness of the oligarchy against C. Flaminius was conveyed to Polybius in the middle of the next century by his aristocratic sources:

The Romans distributed the so-called Ager Picenus in Cisalpine Gaul (the Po valley), from which they had ejected the Gauls known as Senones when they defeated them; C. Flaminius was the originator of this demagogic policy, which one may describe, as it were, as the first step at Rome taken by the people away from the straight and narrow path (of subservience to the oligarchy) and which one may regard as the cause of the war which followed against the Gauls. For many of the Gauls, and particularly the Boii, took action because their territory now bordered on that of Rome, thinking that the Romans no longer made war on them over supremacy and control, but in order to destroy and eliminate them completely (Polybius II, 27, 7–9).

The reasons for senatorial opposition to the proposal of C. Flaminius are not hard to guess – not any theoretical concern with the effect of an extension of Roman territory on the functioning of the city-state, but simple apprehension of the rewards awaiting C. Flaminius in terms of prestige and clients.

Nor was the law of 232 the only thing which alienated C. Flaminius from the senate:

(He was) hated by the senators because of a recent law, which Q. Claudius as tribune had passed against the senate and indeed with the support of only one senator, C. Flaminius; its provisions were that no senator or son of a senator might own a sea-going ship, of more than 300 amphoras’ carrying capacity; that seemed enough for the transport of produce from a senator’s estate; all commercial activity seemed unsuitable for senators. The affair roused storms of controversy and generated hostility to C. Flaminius among the nobility because of his support for the law, but brought him popular backing and thence a second consulate (Livy XXI, 63, 3–4).

The law was without practical consequences, since a senator could engage in commercial activity through an intermediary, as the elder Cato, that upholder of traditional values, discovered; rather, the law accurately expressed a fundamental belief of the Roman governing class, that a gentleman should live off the land, or at any rate seem to do so. The chief importance of the law was that it involved public recognition of the senate as the governing council of the Roman community (and indeed of a senator and his son as belonging to a distinct Order in society); the law insisted that its members should be above worldly considerations.3 The law also provided evidence of the willingness of the people to legislate for the conduct of their leaders; that was its offence – an offence that came to be repeated more than once as the revolution of the late Republic unfolded.

The second consulship which his support for the Lex Claudia brought C. Flaminius was that of 217; defeat at Lake Trasimene cost him his life and provided further material with which the oligarchy could blacken his memory. But he was not the last leader whom during the Hannibalic War the people brought to office against the wishes of the oligarchy. C. Terentius Varro, one of the consuls for 216, came to office partly as a result of popular dissatisfaction with the oligarchy’s conduct of the war (Livy XXII, 34, 8, is also a plausible reconstruction of part of the ideology of his supporters); the policy associated with the name of Q. Fabius Maximus, of avoiding battles with Hannibal, was supposed to involve prolongation of a war which could easily by won outright. C. Terentius Varro took the Roman legions down to the greatest defeat of the war at Cannae.

Despite his failure, the rumblings continued. Not surprisingly, one reaction of the oligarchy to crisis during the Hannibalic War was to authorize a consul to name a dictator, in office for six months with supreme power. This emergency office was reduced to a nonsense in 217 when the people elevated M. Minucius Rufus to a dictatorship alongside Q. Fabius Maximus; ironically, the senate itself weakened the position of Maximus by quibbling over his access to finance for ransoming prisoners. The people again nominated a dictator in 210; and in that year tribunician interference with the activity of a dictator was allowed for the first time. The office fell into desuetude and its function was taken over when need arose by a very different institution (see here); the office itself was revived in a very different form by Sulla and Caesar.

But the most remarkable product of popular feeling during the Hannibalic War was the emergence of a charismatic leader who for the moment avoided any overt challenge to the collective rule of the oligarchy, but whose example had nonetheless the most sinister implications for the future, P. Cornelius Scipio. Carried by popular fervour to the command in Spain, he there found himself hailed as king by some native Spanish troops; he turned the embarrassing compliment by creating the title imperator for them to use. The title was initially monopolized by members of his family and then competed for in the escalating political struggles of the late Republic. The victory over Carthage at Zama then gave Scipio the title of Africanus and a degree of eminence over his peers never before achieved. He even claimed a special relationship with Jupiter. Also symptomatic of the degree of eminence which an individual could achieve in this period is the cult offered to Marcellus, the captor of Syracuse, by that city (we do not know whether in his lifetime or posthumously). For the moment, however, senatorial control was unchallenged; the astonishing thing is not that the assembly in 200 refused initially to vote for another war, with Philip V of Macedon, but that it was persuaded so readily to change its mind. Such was the grip of the oligarchy on the Roman state.

1. Records of temple foundations appear to have been preserved independently of the main historical tradition (see here).

2. It is also interesting that at some time the Romans acquired the word macellum, market, from a Phoenician source.

3. It is unreasonable to suppose with some scholars that the law was motivated by the desire of men of business to eliminate competition from senators.

VI The Conquest of the East

ROMAN POLITICAL involvement east of the Adriatic began with the First Illyrian War in 229, an event as crucial to our understanding of Roman expansion as to that of Polybius, with his Hellenocentric view of the ‘world’ conquered by the Romans. According to Polybius, the Illyrians (Map 3), long in the habit of molesting ships sailing from Italy, did so even more when in the course of the reign of Queen Teuta of Illyria they seized control of Phoenice; a Roman protest led to the murder of L. Coruncanius, one of the Roman ambassadors, on his way home and war was declared. Roman distaste for a queen who could not or would not control her subjects’ piracy is intelligible enough and one can compare the Roman punishment of their troops who seized Rhegium in 280; but the strategic threat posed by Illyria with its capital at Rhizon on the bay of Kotor should not be underestimated. ‘Whoever holds Kotor, I hold him to be master of the Adriatic and to have it within his power to make a descent on Italy and thereby surround it by land and sea’ remarked Saint-Gouard in 1572. Of the power of Illyria after the seizure of Phoenice Rome had tangible evidence in the shape of the pleas of those who suffered.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.