Полная версия

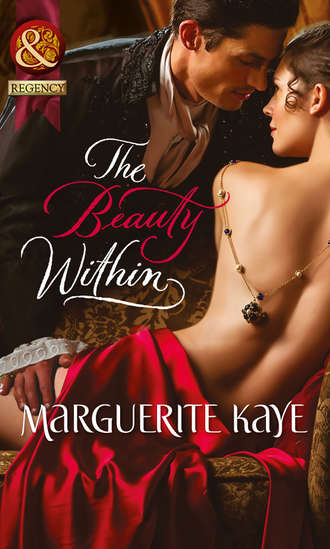

The Beauty Within

Though she had never aspired to being a wit, Bella had been happy to be labelled vivacious, and had always been extremely sociable until her husband made it clear that her lack of political nous made her something of a liability. He summarily replaced her at the head of his political table with his sister and, having made sure that she was impregnated, consigned his wife to the country. Here, Bella had remained, popping out healthy Armstrong boys at regular intervals, taking pleasure in her sons but in very little else. Though she knew it would displease her husband, she longed for this next child to be a daughter, the consolation prize she surely deserved, who would provide her mama with the affection she craved.

Disappointed from a very early stage in her marriage, unable to express her disappointment to the man responsible, Bella had turned her ire instead on his daughters, who made it very easy for her to do so since they made it all too obvious that they thought her a usurper. Her malice had become a habit she did not even contemplate breaking. Pregnant, bloated, lonely and bored, it was hardly surprising, then, that Giovanni, his breathtaking masculine beauty enhanced by the austerity of his black attire, would appear to her like a gift from the gods she thought had abandoned her.

‘Lady Armstrong, it is an honour,’ he said, bowing over her dimpled and be-ringed hand as she lay on the chaise-longue, ‘and a pleasure.’

Bella simpered breathlessly. She had never in all her days seen such a divine specimen of manhood. ‘I can tell from your delightful accent that you are Italian.’

‘Tuscan,’ Cressie said tersely, unaccountably annoyed by the extraordinary effect Giovanni was having on her stepmother. She sat down in a chair opposite and gazed pointedly at Lady Armstrong’s prostrate form. ‘Are you feeling poorly again? Perhaps we should leave you to take tea alone?’

Flushing, Bella pushed aside the soft cashmere scarf which covered her knees, and struggled upright. ‘Thank you, Cressida. I am quite well enough to pour Signor di Matteo a cup of tea. Milk or lemon, signor? Neither? Oh well, of course I suppose you Italians do not drink much tea. An English habit I confess I myself am very fond of. Cake? Well then, if you do not, I shall have to eat your slice else cook will be mortally offended, for Cressida, you know, has not a sweet tooth. Perhaps if she did, her temperament might improve somewhat. My stepdaughter is very serious, as you will no doubt have gathered by now, signor. Cake is far too frivolous a thing for Cressida to enjoy. You know, of course, that she is presently acting governess to two of my sons? James and Harry. You will be wishing to know more about them, I dare say, if you are to do justice to my angels.’ Finally stopping for breath, Bella beamed and ingested the greater part of a wedge of jam sponge.

‘Lord Armstrong informs me that his sons are charming,’ Giovanni said into the silence which was broken only by his hostess’s munching. She nodded and inhaled another inch or so of cake. Fascinated by the way she managed to consume so much into such a comparatively small mouth, he was momentarily at a loss.

Brushing the crumbs from her fingers, Bella launched once more into speech, this time a eulogy on the many and manifold charms of her dear boys. ‘They are so very fond of their little jokes too,’ she trilled. ‘Cressida claims they lack discipline, but I tell her that it is a question of respect.’ Bella cast a malicious smile at her stepdaughter. ‘One cannot force-feed such intelligent children a lot of boring facts. Such a method of teaching is all very well for little girls, most likely, but with boys as lively as mine—well, I am not one to criticise, but I do think it was a mistake, not hiring a qualified governess to replace dear Miss Meacham.’

‘Dear Miss Meacham left because she could no longer tolerate my brothers’ so-called liveliness,’ Cressie interjected.

‘Oh, nonsense. Why must you always put such a negative slant on everything your brothers do? Miss Meacham left because she felt she was not up to the job of tutoring such clever children. “I wish fervently they get what they deserve” is what she said to me when she left, and I heartily agree. I don’t know what your father was thinking of, to be perfectly honest, entrusting you with such a role, Cressida. Though perhaps it is more of a question of not knowing what role to assign you, since you are plainly unsuited to play the wife. After—how many years is it now, since I launched you?’

‘Six.’

Bella shook her head at Giovanni. ‘Six years, and despite the best efforts of myself and her father, she has not been able to bring a single man up to scratch,’ she said sweetly. ‘I am not one to boast, but I had Caroline off my hands with very little fuss, and I have no doubt that Cordelia will go off even more quickly. You have not met Cressida’s sisters, but sadly she has none of their looks. Even Celia, the eldest, you know, who lives in Arabia, has her charms, though it was always Cassandra who was the acknowledged beauty. I suppose one plain sister out of five is to be expected. If only she were not such a blue-stocking, I really do believe I could have done something with her.’ Bella shrugged and smiled sweetly again at Giovanni. ‘But she scared them all off.’

Realising that she was in danger of looking like a petulant child, Cressie tried not to glower. The words so closely echoed her father’s that she was for a moment convinced he and Bella were conspiring to belittle her. Though Bella had said nothing new, nor indeed anything which Cressie had not already blurted out to Giovanni upon their first meeting, it was embarrassing to have to listen to her character being dissected in such a way. So much for all her attempts to think more kindly of her stepmother. As to what Giovanni must be making of Bella’s shocking manners, it didn’t bear thinking about.

She put down her tea cup with a crack, determined to turn the conversation to the matter of the portrait, but Bella, having refreshed herself with a cream horn, was not finished. ‘I remember now, there was a man your father and I thought might actually make a match of it with you. What was his name, Cressida? Fair hair, very reserved, a clever young man? You seemed quite taken with him. I remember saying to your father, she’ll surely reel this one in. In fact, as I recall, you actually told us he was going to call, but he never did. He took up a commission shortly after, now I come to think of it. Come now, you must remember him, for it is not as if you were crushed by suitors. Oh, what was his name?’

She could feel the flush creeping up her neck. Think cold, Cressie told herself. Ice. Snow. But it made no difference. Perspiration prickled in the small of her back. Having taught herself never to think of him, she had persuaded herself that Bella would have forgotten all about …

‘Giles!’ Bella exclaimed. ‘Giles Peyton.’

‘Bella, I’m sure that Signor di Matteo …’

‘He was actually quite presentable, once one got over his shyness. My lord thought it was a good match. He is not often wrong, but in this instance—the fact is, men do not like clever women. My husband’s first wife, Catherine, was reputed to be a bit of a blue-stocking, and look where it got her—five daughters, and dead before the last was out of swaddling. When he asked for my hand, Lord Armstrong told me that it was my being so very different from his first wife that appealed to him, which I thought was a lovely compliment. No, men do not like a clever woman. I am sure you agree, signor?’

Blithely helping herself to another pastry, Bella looked enquiringly at Giovanni, but before he could speak, Cressie got to her feet. ‘Signor di Matteo came here to paint my brothers’ portrait, Bella, not to discuss what he finds attractive in a woman.’ She swallowed hard. ‘I beg your pardon. And yours, Signor di Matteo. If you will excuse me, I have a headache, which is making me forget my manners.’

‘I hope you are not thinking of retiring to your room, Cressida. James and Harry …’

‘I am perfectly aware of my duties, thank you.’

‘If you wish to be excused from dinner, however, I am sure that Signor di Matteo and I can manage quite well without your company.’

‘I am sure that you can,’ Cressie muttered, wanting only to be gone before she lost her temper completely, or burst into tears. One or other, or more likely both, seemed imminent, and she was determined not to allow Bella the satisfaction of seeing just how upset she was.

But as she turned to go, Giovanni got to his feet. ‘I must inform you that you are mistaken on several counts, Lady Armstrong,’ he said curtly. ‘Firstly, there are many enlightened men, and I include myself among them, who enjoy the company of a clever woman very much. Secondly, I am afraid that I prefer to dine alone when I am working. If I may be excused, I would like the governess to introduce me to her charges.’

With a very Italian click of the heels and a very shallow bow, Giovanni took his leave, took Cressie’s arm in an extremely firm grip and marched them both out of the drawing room.

‘Lady Cressida. Cressie. Stop. The boys can wait a few moments longer. You are shaking.’ Opening a door at random, Giovanni led her into a small room, obviously no longer used for it was musty, the shutters drawn. ‘Here, sit down. I am not surprised that you are so upset. Your stepmother’s bitterness is exceeded only by her ability to devour cake.’

To his relief, Cressie laughed. ‘My sisters and I used to think her the wicked stepmother straight out of a fairytale. I don’t know why she hates us so—though my father is right, we have given her little cause to love us.’

‘Five daughters, all cleverer than she, and all far more attractive …’

‘Four of them more attractive.’

‘To continue the fairytale metaphor, why are you so determined to be the ugly sister?’

Cressie shrugged. ‘Because it’s true. Because it’s how it has always been. Do you have any brothers or sisters?’

‘No.’ At least, none who acknowledged him, which amounted to the same thing. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘I wondered if all families are the same. In mine, we were labelled by my father, pretty much from birth. Celia is the diplomat, Cassie the pretty one, Caroline the dutiful one who can always be depended upon, Cordelia the charming one and I—I am the plain one. Upon occasion I am classed the clever one, but believe me, my father uses that only as an insult. He doesn’t see beyond his labels, not even with Celia, whom he was most proud of because of her being so useful to him.’

Giovanni frowned. ‘But he does precisely the same to your stepmother. She is the brood mare—it is her only purpose. It is no wonder she feels inferior, and no wonder that she must disguise it by trying always to put you in your place. She is vulgar and brash and lonely, so she takes it out on you and your sisters. It is not excusable, but it is understandable.’

‘I hadn’t thought—oh, I don’t know, perhaps you are right, but I am not feeling particularly charitable towards her at the moment.’

Cressie had been worrying at a loose thread of skin on her pinkie, and now it had started to bleed. Without thinking, Giovanni lifted her hand and dabbed the blood with his fingertip before it could drip on to her gown. He put his finger to his lips and licked off the blood. She made no sound, made no move, only stared at him with those amazingly blue eyes. They reminded him of early morning fishing trips back home in his boyhood, the sea sparkling as his father’s boat rocked on the waves. The man he’d thought was his father.

With his hand around her slender wrist, his lips closed around her finger and he sucked gently. Sliding her finger slowly out of his mouth, he allowed his tongue to trail along her palm, let his lips caress the soft pad of her thumb. Desire, a bolt of blood thundered straight to his groin, taking him utterly by surprise. What was he doing?

He jumped to his feet, pulling the skirts of his coat around him to hide his all too obviously inflamed state. ‘I was just trying to prevent—I’m sorry, I should not have behaved so—inappropriately,’ he said tersely. She should have stopped him! Why had she not stopped him? Because for her, it meant nothing more than he had intended, an instinctive act of kindness to prevent her ruining her gown. And that was all it was. His arousal was merely instinct. He did not really desire her. Not at all.

‘It has been a long day,’ Giovanni said, forcing a cold little smile. ‘With your permission, I think I would like to meet my subjects now, and then I will set up my studio. I will dine there too, if you would be so good as to have some food sent up.’

‘You won’t change your mind and sup with us?’

She looked so forlorn that he almost surrendered. Giovanni shook his head decisively. ‘I told you, when I am working, distractions are unwelcome. I need to concentrate.’

‘Yes. Of course. I understand completely,’ Cressie said, getting to her feet. ‘Painting me would be a distraction too. We should abandon our little experiment.’

‘No!’ He caught her arm as she turned towards the door. ‘I want to paint you, Cressie. I need to paint you. To prove you wrong, I mean,’ he added. ‘To prove that painting is not merely a set of rules, that beauty is in the eye of the artist.’ He traced the shape of her face with his finger, from her furrowed brow, down the softness of her cheek to her chin. ‘You will help me do that, yes?’

She stared up at him, her eyes unreadable, and then surprised him with a twisted little smile. ‘Oh, I doubt very much that you’ll be able to make me beautiful. In fact, I shall do my very best to make sure you cannot, for you must know that my theory depends upon it.’

Chapter Three

Cressie stood at the window of the schoolroom at the top of the house, and looked on distractedly as James and Harry laboured at their sums. The twins, George and Frederick, sat at the next desk, busy with their coloured chalks. An unusual silence prevailed. For once, all four boys were behaving themselves, having been promised the treat of afternoon tea with their mama if they did. In the corner of the room, a large pad of paper balanced on his knee, Giovanni worked on the preliminary sketches for their portrait, unheeded by his subjects but not by their sister.

He seemed utterly engrossed in his work, Cressie thought. He would not let her look at the drawings, so she looked instead at him, which was no hardship—he really was quite beautiful, all the more so with the perfection of his profile marred by the frown which emphasised the satyr in his features. That, and the sharpness of his cheekbones, the firm line of his jaw, which contrasted so severely with the fullness of his lips, the thick silkiness of his lashes, made what could have been feminine most decidedly male.

His fingers were long and elegant, almost unmarked by the charcoal he held. Her own hands were dry with chalk dust, her dress rumpled and grubby where Harry had grabbed hold of it. No doubt her hair was in its usual state of disarray. Giovanni’s clothes, on the other hand, were immaculate. He had put off his coat and rolled up the sleeves of his shirt most precisely. She could not imagine him dishevelled. His forearms were tanned, covered in silky black hair. Sinewy rather than muscular. He was lithe rather than brawny. Feline? No, that was not the word. He had not the look of a predator, and though there was something innately sensual in his looks, there was also a glistening hardness, like a polished diamond. If it had not been such a cliché, she would have been tempted to call him devilish.

She watched him studying the boys. His gaze was cool, analytical, almost distant. He looked at them as if they were objects rather than people. Her brothers had, when first introduced to Giovanni, been obstreperous, showing off, vying for his attention. His utter indifference to their antics had quite thrown them, so used were they to being petted and spoilt, so sure were they of their place at the centre of the universe. Cressie had had to bite her lip to stop herself laughing. To be ignored was beyond her brothers’ ken. She ought to remember how effective a tactic it was.

She turned her gaze to the view from the window. This afternoon, it had been agreed, Giovanni would begin her portrait. Thesis first, he said, an idealised Lady Cressida. How had he put it? A picture-perfect version of the person she presented to the world. She wasn’t quite sure what he meant, but it made her uncomfortable, the implication that he could see what others could or would not. Did he sense her frustration with her lot? Or, heaven forefend, her private shame regarding Giles? Did he think her unhappy? Was she unhappy? For goodness’ sake, it was just a picture, no need to tie herself in knots over it!

Giovanni had earmarked one of the attics for their studio, where the light flooded through the dormer windows until early evening and they could be alone, undisturbed by the household. In order to free her time, Cressie had volunteered to take all four boys every morning, leaving Janey, the nursery maid, in charge in the afternoons, which Bella usually slept through after taking tea. Later today, Giovanni would begin the process of turning Cressie into her own proof, painting her according to the mathematical rules she had studied, representing her theorem on canvas. Her image in oils would be a glossy version of her real self. And the second painting, depicting her alter ego, the private Cressie, would be the companion piece. How would Giovanni depict that version of her, the Cressie he believed she kept tightly buttoned-up inside herself? And were either versions of her image really anything to do with her? Would it be the paintings which were beautiful or the subject, in the eyes of their creator? So excited had she been by the idea of the portraits she had thought of them only in the abstract. But someone—who was it?—claimed that the artist could see into the soul. Giovanni would know the answer, but she would not ask him. She did not want anyone to see into her soul. Not that she believed it was true.

Turning from the window, she caught his unwavering stare. How long had he been looking at her? His hand flew across the paper, capturing what he saw, capturing her, not her brothers. His hand moved, but his gaze did not. The intensity of it made it seem as if they were alone in the schoolroom. Her own hand went self-consciously to her hair. She didn’t like being looked at like this. It made her feel—not naked, but stripped. No one looked at her like that, really looked at her. Intimately.

Cressie cleared her throat, making a show of checking the clock on the wall. ‘James, Harry, let me see how you have got on with your sums.’ Sliding a glance at Giovanni, she saw he had moved to a fresh sheet of paper and was once again sketching the boys. Had she imagined the connection between them? Only now that it was broken did she notice that her heart was hammering, her mouth was dry.

She was being silly. Giovanni was an artist, she was a subject, that was all. He was simply analysing her, dissecting her features, as a scientist would a specimen. Men as beautiful as Giovanni di Matteo were not interested in women as plain as Cressie Armstrong, and Cressie would do well to remember that.

It was warm in the attic, the afternoon sun having heated the airless room. Dust motes floated and eddied in the thermals. Giovanni removed his coat and rolled up the sleeves of his shirt. In front of him, a blank canvas was propped on his easel. Across the room, posed awkwardly on a red velvet chair, was Cressie. He had discovered the chair in another of the attic’s warren of rooms and had thought it an ideal symbolic device for his composition. It was formal, functional and yet sensual, a little like the woman perched uncomfortably on it. He smiled at her reassuringly. ‘You look like the French queen on her way to the guillotine. I am going to take your likeness, not chop off your head.’

She laughed at that, but it was perfunctory. ‘If you take my likeness, then you will have lost, signor. I am—’

‘If you remind me once more of your lack of beauty, signorina, I will be tempted to cut off your head after all.’ Giovanni sighed in exasperation. Though he knew exactly how he wished to portray her, she was far too tense for him to begin. ‘Come over here, let me explain a little of the process.’

He replaced the canvas with his drawing board, tacking a large sheet of paper to it. Cressie approached cautiously, as if the blank page might attack her. All morning, she had been subdued, almost defensive. ‘There is nothing to be afraid of,’ he said, drawing her closer.

‘I’m not afraid.’

She pouted and crossed her arms. Her buttoned-up look. Or was it buttoned-down? ‘I have never come across such a reluctant subject,’ Giovanni said. ‘You are surely not afraid I will steal your soul?’

‘What made you say that?’

She was glaring at him now, which did not at all augur well. ‘It is said that a painting reflects the soul in the same way a mirror does. To have your image taken, some say, is to surrender your soul. I meant it as a jest, Cressie. A mathematician such as yourself could not possibly believe such nonsense.’

She stared at the blank sheet of paper, her brow furrowed. ‘Was it Holbein? The artist who painted the soul in the eyes, I mean. Was that Holbein? I couldn’t remember earlier, in the schoolroom.’

‘Hans Holbein the Younger. Is that what you are afraid of, that I will not steal your soul but see into it?’

‘Of course not. I don’t know why I even mentioned it.’ She gave herself a little shake and forced a smile. ‘The process. You said you would explain.’

Most of his subjects, especially the women, were only too ready to bare their soul to him, usually as a prelude to the offer to bare their bodies. Cressie, on the other hand, seemed determined to reveal nothing of herself. Her guard was well and truly up, but he knew her well enough now to know how to evade it. Giovanni picked up a piece of charcoal and turned towards the drawing board.

‘First, I divide the canvas up into equal segments like this.’ He sketched out a grid. ‘I want you to be exactly at the centre of the painting, so your face will be dissected by this line, which will run straight down the middle of your body, aligning your profile and your hands which define the thirds into which the portrait will be divided, like this—you see how the proportions are already forming on the vertical?’

He turned from the shapes he had sketched in charcoal to find that Cressie looked confused. ‘There is a symmetry in the body, in the way the body can be posed, that is naturally pleasing. If you clasp your hands so, can you not see it, this line?’

Giovanni ran his finger from the top of her head, down the line of her nose, to her mouth. He carried on, ignoring the softness of her lips, tracing the line of her chin, her throat, to where her skin disappeared beneath the neck of her gown. The fabric which formed a barrier made it perfectly acceptable for him to complete his demonstration, he told himself, just tracing the valley between her breasts, the soft swell of her stomach, finally resting his finger on her hands. ‘This line …’ He cleared his throat, trying to distance himself. ‘This line …’ he turned towards the paper on the easel once more and picked up the charcoal ‘… it is the axis for the portrait. And your elbows, they will form the widest point, creating a triangle thus.’

To his relief, Cressie was frowning in concentration, focused on the drawing board, seemingly oblivious to the way his body was reacting to hers. It was because he so habitually avoided human contact, that was all. An instinctive reaction he would not repeat because he would not touch her again. Not more than was strictly necessary.

‘Are you always so precise when you are structuring a portrait?’ she asked. ‘This grid, will you draw it out on the canvas?’