Полная версия

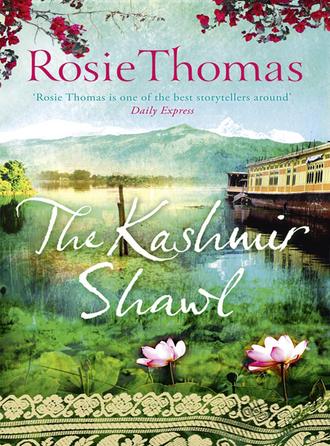

The Kashmir Shawl

Their eyes met. Bruno’s manner was extremely dry but there was a strong reverberation of humour in him. He was Swiss but also quite un-Swiss. That made him interesting as well as attractive, Mair thought. ‘Are you religious?’ she asked.

He shook his head decisively. ‘No. You?’

‘Not at all. But my grandfather was a missionary. He and my grandmother were out here in the 1940s, with the Welsh Presbyterian mission outreach to Leh.’

‘That’s why you’re here now?’

‘My father died recently. His parents were part of our lives because they lived nearby, but we never knew my maternal grandpa and grandma. My mother died when I was in my early teens so that part of the story was lost. I want to try to uncover some of it.’

Mair rarely talked about her mother, even to Hattie. Her instinct was to protect the bruise that had been left by her death. So it was startling to find herself confiding to Bruno Becker this intimate detail, and to realise that since their first encounter and her explanation of the somersaults she hadn’t told Karen one thing about herself.

She had begun to, she remembered, but something else had always intervened.

But Karen was a bright flame, and everyone was drawn to her. It was only the strange circumstances, the snowstorm and their temporary captivity under the shadow of the monastery, that were making Mair talk so unguardedly to Karen’s husband.

She took another hasty mouthful of cognac. Her hand was unsteady and the metal rim of the beaker rattled faintly against her teeth.

‘Go on,’ Bruno murmured.

She told him about the shawl, and her discoveries in Changthang and Leh. He listened attentively, his black head tipped against the stone wall and his eyes on her face. The cook measured some scant handfuls of rice into another pan of water as the scent of mutton swirled through the kitchen.

Bruno enjoyed the story of Tsering’s great-uncle, and the old man’s early memory of listening in amazement to the mission’s wireless set. ‘And now you’re following the shawl thread onwards to Srinagar,’ he said at length.

‘Yes. Who knows what I’ll find there?’ I will find out about the photograph, she thought.

He unscrewed the cap of the flask and poured them both another drink. She sipped hers, stretching out her legs and letting her shoulders drop. The long day of bouncing over potholes had left her muscles aching.

Bruno rotated his beaker, thoughtfully examining the reflections in the polished surface. ‘I am lucky in that both my parents are still alive. They divorced long ago and my mother remarried. She lives near us in Geneva now – she adores Lotus. My father is still physically strong but his memory has almost gone. My sister and I agreed that he would be safer and happier in a special hospital, which is not nearly as bad as it sounds, by the way.

‘When I went to see him just before we came out here, we were sitting on his balcony looking at the mountains and I was talking – I have to talk a lot on these visits. He likes to hear about the rest of the world and everyone’s lives, although I’m not sure how much of it he remembers. I was telling him about all the places we’d be visiting, and he seemed to be listening, nodding, the way he does.

‘Then he reminded me that an Indian friend of our family was originally from Kashmir. Memory is a strange commodity. He remembered the minute circumstances of the friend and her mother coming to Switzerland after the war, yet sometimes he can’t even quite recall who I am. He made me promise that I’d look up the daughter when we get to Delhi.’

Mair nodded, recalling how her father in his last weeks had travelled further and further into the past.

‘The mother would have been the same generation as your grandparents. She was a Christian, a Roman Catholic. Perhaps they knew each other.’

‘Is that likely? It’s a long way from Leh to Srinagar.’

Bruno sighed. ‘And that’s in good weather. Tonight Srinagar might as well be located in South America.’

‘I don’t actually know if my grandparents would ever have come this far west. But it’s not impossible.’ She thought of the photograph again.

‘It would do no harm to ask our friend. If we’re in Delhi at the same time, perhaps you could come with me to visit her.’

Their eyes met again.

‘I’d like that,’ Mair said.

They sat back, relaxed by brandy and conversation.

The languid cooking of dinner continued and a small girl made a circuit of the mattress seats, dishing out metal plates and spoons. Bruno got up once and went to look out at the weather, coming back with a grave face. ‘Getting out of here is going to be difficult,’ he said.

Deep snow would by now be blocking the mountain roads in either direction. Mair could envisage the scale of the work that would be involved in clearing it.

One of the drivers looked across at Bruno. He gave a shrug and an expressive flutter of one hand. ‘Very bad. Very early,’ he called.

Bruno nodded. ‘Very bad,’ he agreed. He folded himself on to the mattress again, telling Mair, ‘We’d have trouble dealing with a sudden huge snowfall like this in Switzerland, let alone here.’

Remembering what Karen had told her, she asked, ‘Are you from Geneva originally?’

Immediately his angular face lost some shadows and he leant closer, almost confidingly. Unwittingly Mair had touched something in him.

‘I have to live in horizontal Switzerland, these days, because that’s where my work is. I’m an engineer. But my home and my roots are in vertical Switzerland, in the mountains. I come originally from the Bernese Oberland, near Grindelwald. Do you know it?’

‘No.’ The claustrophobic room, the knowledge that they were all temporarily captive, made Mair long to be transported by a story. In her mind’s eye she saw a Heidi-picture of sunlit Alpine meadows and dark fir trees. ‘Tell me about it.’

‘My people were farmers,’ he began. ‘In summer they took the cows up to the Alps to pasture. In winter there was snow.’

She listened contentedly. She was warm at last, and Bruno’s description of home was familiar, not so much in the precise details but in the way he talked about the rhythms of farming and the small doings of rural valleys. She also clearly heard what he was not saying, in as many words, about his deep-rooted affection for the place and – she was certain – his longing for it. It made her think of her own home. She wasn’t homesick, as she had been in Leh, but rather sharply alive to the memories of a place that was lost.

Bruno was telling her how the Swiss mountain farmers in the first half of the nineteenth century had known the hidden ways across the high passes connecting remote valleys. They were poor people, and when the first tourists had begun to arrive in the Alps, the Beckers and their neighbours had discovered they could earn good money by guiding visitors. Until then, he said, no one had ever explored the peaks and glaciers just for pleasure. To travel to the neighbouring valleys to find work or to sell their cheeses or even to make a pilgrimage to a mountain shrine, perhaps, but not for the mere satisfaction of it, or even for the sake of some obscure scientific observation. But then the gentlemen mountaineers and amateur scientists had arrived, and ventured up in the tracks of the local men, and after they had conquered their peaks, they rushed home to describe their triumphs and catalogue their discoveries.

The news spread, and more and more of them flocked to the Alps. Soon the wealthy messieurs were arriving in their hundreds from all over Europe, and the Beckers were among the first to offer themselves for hire as professional mountain guides.

‘My great-grandfather, for example, he was Edward Whymper’s guide,’ Bruno said.

Mair had never heard of Whymper, and admitted as much. Bruno raised an eyebrow. ‘He was British. He made the first ascent of the Matterhorn, with his Zermatt guides. There was a tragedy on the way down and four men died, but Whymper himself survived. He came regularly to climb in the Oberland and he often took Christian Becker as his guide. In the next generation – that was in the twenties and thirties, my grandfather Victor and another client made an early attempt on the Eiger’s north face, only just escaping with their lives from a terrible storm. Victor saved the client’s life.’

‘You must be proud of that.’

He gave a quick nod. ‘We are.’

‘I don’t know any mountaineers.’ But now another memory came to her. ‘I saw a memorial in Leh, in the European cemetery. Nanga Parbat.’ She could bring to mind the name of the mountain, but not that of the dead man.

Bruno supplied it for her. ‘Matthew Forbes. He was a mathematician from Cambridge University, a brilliant young man.’

‘You saw the memorial too?’

‘I visited it, yes. That Nanga Parbat expedition was led by a Swiss named Rainer Stamm, and he was the man whose life was saved on the Eiger by my grandfather. The two of them were close friends from that day on.’

So she and Bruno both had their reasons for visiting the cemetery. The link between them seemed significantly strengthened by this association of history. What with this and the snow, and the altitude-enhanced effects of the cognac, she could almost imagine how she might let her head tip sideways, gently and slowly, until it came to rest on Bruno Becker’s shoulder.

And when she glanced at him she realised, with a faint shock of pleasure as well as a clutch of utter dismay, that he was imagining the same thing.

She levered herself upright and pressed her spine into the cold stone. Bruno shifted his position too.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.