Полная версия

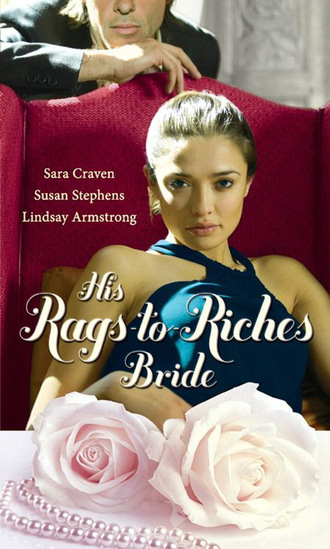

His Rags-to-Riches Bride

She watched him go, controlling an impulse to run after him. Beg him not to leave her. Because she had to be strong, she thought. Starting now.

As she heard the car’s engine die away someone said her name, and she saw Jamie emerging from the drawing room, his face pale and set.

He came over and gave her an awkward hug. ‘God, sis, I can’t believe it, can you? I keep thinking that I’m going to wake up at any moment, and find it’s all been a bad dream.’ He looked past her. ‘Where’s Dan? They’ve both been asking for him.’

‘He had to go.’ She hesitated. ‘Jamie, I don’t want to seem heartless, but wouldn’t it be better if Candida could be looked after by her own family? We’re going to have our hands full.’

‘I suggested it, naturally, but it seems she doesn’t get on with her mother.’ He shook his head. ‘The drive down was a nightmare. She kept saying that Annapurna was cursed, and she’d known something dreadful was going to happen. You can imagine the effect that had on Ma,’ he added heavily.

She nodded. ‘Is she using Simon’s room?’

‘Well, yes. She just walked in there and shut the door. I—didn’t know what to say. After all, it’s where she’s always slept when she’s stayed here, I suppose.’

She sighed. ‘I suppose so too—and yet.’ She patted his shoulder. ‘I’ll go and sit with Mother. Wait for her to wake up.’

And wait for Dan to come back too. Because he was Simon’s best friend, and for that reason, if no other, he’ll be here for us. Or for a while, at least. Until the mourning time is over, and we all pick up our lives again somehow.

She did not dare look any further into the future than that. Because she knew it would be like staring down into an abyss. A terrible place that she had never known existed until this moment. But which seemed, somehow, to have been waiting for her the whole of her life.

CHAPTER FIVE

SHE moved at last, slowly and stiffly, wondering just how long she’d been sitting there, staring into space. Knowing, however, that it was getting late, and that she had no wish to be found hanging round like a cobweb in the corner when Daniel returned.

On the other hand, she felt too much on edge to guarantee she was going to get the night’s sleep she so badly needed. She had embarked on a long and painful journey, she thought with a pang, and it was not finished yet. Not by any means.

But once it was over, and the past had finally been laid to rest, she might be able to find peace—of a kind.

In the short term, something soothing to drink might help, she decided, trailing into the kitchen. Perhaps Mrs Evershott’s tried and trusted remedy for insomnia would be the answer.

She heated milk and poured it into a beaker, adding a spoonful of honey and a grating of nutmeg, wondering, as she did so, what had happened to the housekeeper who’d looked after them all for so long. Hoping that she’d found a family who would value her as she deserved, and not become another casualty of the upheaval that had affected all their lives.

She took the beaker into the room she would now have to think of as hers, and sipped the milk slowly as she prepared for bed. Her final action before she climbed under the covers was to return her address book to her bag.

It would be far better at this stage simply to keep quiet about her return, she told herself. To find a job, keep her head down, and wait for Daniel to finish refurbishing his property and move out before she made contact with any old friends.

It would not be for long, she told herself. Nothing lasted for ever—not joy, not grief, perhaps not love either—and this present situation would also pass—eventually.

She might even be able to make a joke of it. It was hideously awkward, of course. And as he was leaving we agreed it was just as well we didn’t stay married, or we’d have surely killed each other.

Or she could be terribly casual and civilised instead. No, it wasn’t really a problem. We were always friends, you know, long before the marriage thing. And now we’re friends again, so it worked out well, in a funny way.

It might be better not to mention it at all. Pretend it had never happened.

She stifled a sigh. She would decide on her approach as and when it became necessary. And for the time being she had other priorities.

Switching off the lamp, she turned on her side and tried to relax. To compose herself for sleep. But her mind was relentlessly awake and buzzing with images.

With memories as sharp and painful as a knife wound.

Simon’s body, and that of his climbing partner Carlo Marchetti, had never been recovered—even though Daniel had travelled out to the base camp with offers of money and resources to spearhead a renewed search—so it had been a memorial service rather than a funeral that had taken place at their local parish church.

And the days leading up to it had been just as bad as Daniel had warned, or even worse, with Laine’s own grieving process having to be put on hold while she supported her mother through this crisis.

And not just her mother. Because Candida had seemed to take up residence, as if she was Simon’s widow, and Laine had begun to wonder if she had any plans to leave.

At the service Angela had looked ethereal, in a new and expensive black velvet coat, as she’d walked, with Jamie, down the aisle of the crowded church to the front pew. Candida had followed, clinging to Daniel’s arm, thus ensuring that Laine was left to bring up the rear.

Many of the mourners had come back to the house afterwards, and Laine had been kept busy helping Mrs Evershott offer sherry and other refreshments, while her mother had drooped on the sofa, with Candida in close attendance.

And when everyone had gone, it had been time for another ritual—the reading of Simon’s will.

It had been made hurriedly, just before his departure, and he’d only had one thing of real value to bequeath—a flat in Mannion Place, London, which he’d inherited from his father, and left jointly to Jamie and Laine, together with the accruing rent from the flat’s sitting tenants, a Mr and Mrs Beaumont.

‘What is this nonsense?’ Angela was suddenly wilting no longer, but sitting bolt upright, her eyes blazing. ‘That property was part of my husband’s estate. I always understood Simon was to have a life interest only. So it should have reverted to me.’

Mr Hawthorn, the family solicitor, had coughed dryly. ‘No, it was an outright bequest, Mrs Sinclair, and your son was entitled to dispose of it as he saw fit. And his brother and sister are his sole beneficiaries.’

Even in the depth of her bewilderment at this turn of events, Laine was suddenly conscious of Candida’s white face and set mouth, and realised that Simon’s last wishes had not mentioned her either.

Daniel had deliberately stayed away from the reading, and eventually Laine went in search of him, thankful to escape from the house for a while. She found him at the end of the garden, standing on the bank of the river, skimming stones across the surface of the water, his face grim. She said his name with a touch of uncertainty and he turned to look at her, with no lightening of his expression.

‘Is there something you want?’

She tried to smile. ‘Just to get away for a while.’ She paused. ‘I suppose you know about Simon’s legacy?’

It was Dan’s turn to hesitate. ‘He mentioned it—yes. You should be pleased. I gather it’s a valuable piece of real estate.’

‘It must be,’ she said. ‘Judging by the tide of ill-feeling running at the moment.’ She bit her lip. ‘My mother is suggesting that Jamie and I should refuse the bequest and pass the flat, and its rent, over to her.’

‘Well, Jamie must make up his own mind,’ he said flatly. ‘But fortunately any decision is out of your hands until you’re eighteen. And at present I imagine your trustees will take a very different view of the matter.’

‘Maybe Si should have left the flat to Candida,’ she said slowly. ‘After all, she was going to be his wife, and she gets nothing,’ she added, hating herself for not caring more. ‘I suppose he assumed he’d be coming back, and could change things later.’

He turned back to the river. ‘Yes,’ he said harshly. ‘I believe that’s exactly what he thought.’

‘It’s so awful without him,’ she said, in a small, subdued voice. ‘Everything’s such a mess.’

‘More than you know.’ He spoke the words half under his breath, then forced a faint smile as she looked at him in bewilderment. ‘But you’ll soon be out of it, Laine. After all, you’ll be going back to Randalls in a few days.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Is it very dreadful of me to wish I was there now?’

‘No,’ he said quietly. ‘I don’t think so. I think Si would understand completely.’

There was another silence, then she said, ‘The boat’s there,’ nodding towards the elderly dinghy. She added wistfully, ‘Do you think we might go out in it—for old times’ sake?’

‘No time, I’m afraid.’ His voice was crisp and cool. ‘I have to be leaving. I fly to Sydney tomorrow, and I have some stuff to collate before I go.’

‘Oh,’ she said, struggling to hide her disappointment. ‘I see. Yes, of course. And I’d better go back too. They’ll be wondering where I am.’ She hesitated again. ‘Dan—about the flat. Someone should talk to Mother—calm her down like Simon used to do.’ She swallowed. ‘I suppose you couldn’t …?’

‘Too damned right.’ There was real anger in his voice. ‘Get it into your head, Laine. I am not Simon, and I can’t take his place—even if I wanted to. Besides, he couldn’t divert your mother once she’d really got her teeth stuck into a grievance. You know that.’

‘I suppose so.’ She sighed. ‘I don’t know what to do.’

‘Then do nothing,’ he said. ‘She’ll get over it. You concentrate on passing your exams and going off to university next year. You have a career to plan—a future—a whole life. You have to let your mother go her own way, for better or worse.’

‘I’m sorry.’ She was more than sorry. She was mortified. ‘I didn’t mean to impose.’

He said more gently, ‘And I didn’t mean to snap. Maybe a few weeks in Australia will bring me back in a better temper.’

Just as long as it brings you back …

He paused, looking down at her, and for a dizzy moment she thought he was going to touch her cheek. Or even—kiss her. And almost—for one infinitesimal moment—she swayed towards him.

But instead he said quietly, ‘Things will improve with time, Laine. Believe me.’ And walked quickly away.

But he was wrong, Laine thought, twisting restlessly and trying to fight her pillow into a more manageable shape. As she had so soon found out.

It had been three days later, on her return from the village, where she’d been posting another batch of replies to the letters of condolence, that she’d sought out her mother in the drawing room.

She said, ‘I’ve just found my school trunk in the hall. What’s going on? How did it get here?’

Angela was sitting on the sofa, glancing through a fashion magazine. She said, ‘I had it sent for. See that it’s unpacked, please. It’s terribly in the way.’

‘But why?’ Laine stared at her. ‘It’s nowhere near the end of term, and I have stacks of coursework to catch up with. I can’t afford any more time off.’

‘And I can’t afford any more of the expense of keeping you at that school.’ Angela put down the magazine and looked up at her daughter. ‘Therefore I telephoned to Mrs Hallam and said you would not be returning to Randalls because from now on you were needed at home. She quite understood.’

‘Which is more than I do.’ Laine swallowed. ‘Mother, my fees are paid from the bursary—unless it’s been withdrawn for some reason. Has it?’

‘Not as far as I’m aware. But it doesn’t cover everything. Think of all the items of uniform I’ve had to replace, as well as the extras—your piano lessons, for instance. It simply can’t go on.’

Laine felt suddenly very cold. ‘But I have to go back to school. How else am I going to get to university?’

‘I’m afraid you’re not.’ Her mother sounded almost brisk. ‘I’ve only just finished subsidising Jamie, and I’ve no intention of starting again with you. Anyway, I have to consider the running costs of this house, and now that Simon is no longer here to help with the finances savings have to be made.’

She paused. ‘I have therefore decided to let Mrs Evershott go, and we will have to manage the housework and cooking between us.’

‘You’re sacking Evvy?’ Laine was aghast. ‘But you can’t.’

‘I’ve already done so,’ Angela said shortly. ‘While she’s working out her notice you’ll spend time with her, learning how to run the house. Don’t forget it was only last term that I paid a small fortune for you to go on that cookery course in Normandy,’ she added acidly. ‘I only hope it was money well-spent. At any rate, it’s high time you made yourself useful round here.’

Laine’s heart sank like a stone. ‘Please,’ she said. ‘Please say you don’t mean this.’ She swallowed. ‘We’re talking about my life, here.’

‘And what about my life?’ There was a sudden strident note in her mother’s voice. ‘Do you realise what it’s been like for me since your father died? The way I’ve been stuck down here—having to coax people down to stay three weekends out of four to avoid going mad with boredom?’

She got to her feet, walking restlessly round the room. ‘This house has been nothing but a burden for years—and it’s a burden you’re going to share, Elaine, or at least until you’re eighteen.’

She paused, then added brusquely, ‘Ask Mrs Evershott for some plastic bags for your school uniform. You won’t be needing any of it again, and it can go with the rest of the rubbish tomorrow.’

Laine watched her return to her seat and reach for the magazine again. Then she moved, slowly and stiffly, crossing to the door and closing it quietly behind her. She stood for a moment in the hallway, feeling stunned—battered—as if Angela had hit her, knocking her to the floor.

She supposed she’d always known instinctively that she wasn’t her mother’s favourite, but if she’d hoped that they would somehow be drawn closer in their mourning for Simon she now realised how mistaken she was.

I feel as if I don’t know her, she thought. As if I’ve spent my whole life living with a stranger.

Yet, looking back, she could see the resentment had always been there, never far from the surface. But not targeting her—or not openly—and certainly not until then.

However, she soon realised she was not the only sufferer, when she made her reluctant way to the kitchen and saw Mrs Evershott’s white face and compressed lips.

‘Oh, Evvy.’ Distressed, she put her arms round the older woman’s rigid figure and hugged her. ‘I’m so sorry.

‘I would never have believed it,’ the housekeeper said tonelessly. ‘Never credited that Mrs Sinclair could treat me like this after all these years.’ She swallowed. ‘It would never have happened, Miss Laine, if poor Mr Simon had been spared. Never.’

Along with so much else, Laine thought, as she lay, staring sightlessly into the darkness. And especially, crucially, her brief and bitter marriage.

All the demons were out of the box now, tormenting her wincing mind. Reminding her, with merciless precision, of everything that had happened in those bleak, bewildering weeks, when she’d gone from a girl with all her hopes and dreams in front of her to being a glorified domestic servant.

There had been nights at first when she had fallen into bed exhausted from the non-stop cooking and cleaning and her mother’s incessant demands. But she’d been young and strong, and eventually she had established a workable routine largely drawn from her predecessor’s neatly compiled roster of household tasks.

And in the middle of it all she had become eighteen years old. There had been no party—Angela had said tearfully that it was too soon for any celebration—but Celia and some of Laine’s other friends had driven over from Randalls at the weekend and taken her out for a meal in Market Lambton, followed by a visit to its only nightclub, and for a few hours she’d been able to hide her unhappiness behind a shield of music and laughter.

On her actual birthday she had received a watch from her mother, an iPod from Jamie, and a surprise parcel from her late grandmother, sent on by the trustees, which contained Mrs Sinclair’s pearls and her copy of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, complete with the legend of Lancelot and Elaine.

And also out of the blue had come a messengered bouquet of eighteen pink roses from Daniel, with a velvet box tucked in among them holding a pair of gold earrings, shaped like flowers, with a tiny diamond at each centre.

‘Charming,’ Angela commented with a touch of acidity, as Laine shyly showed them off over dinner. ‘But surely a little over the top for a child of your age.’

Jamie leaned forward, his gaze flicking from his mother’s raised brows to Candida’s faint scowl, and smiled. ‘On the contrary,’ he drawled. ‘Maybe Dan’s giving us all a salutary reminder that Lainie’s now officially a woman. And entitled to a life of her own,’ he added pointedly. ‘Together with the ability to make decisions about it.’

There was an odd silence, then, ‘Oh, don’t be absurd,’ Angela said shortly, and turned the conversation to other topics, leaving Laine wondering, and even a little uneasy.

Yet nothing could have prepared her for the bombshell that had exploded a few days later, or its implications for her future.

And for which, even now, she was still experiencing the fallout.

She turned over, punching her pillow into submission, then burying her face in it. Telling herself to relax, because everything would seem better after a good night’s sleep, but knowing at the same time that it wasn’t true.

That the pain would still be there waiting for her when she opened her eyes.

It was very early when she awoke next morning, and she lay for a moment, totally disorientated, listening to the distant hum of city traffic as opposed to the creak of a boat at anchor.

Her eyes felt as if they were full of sand, and her throat was equally dry—almost as if she’d been crying in her sleep, making her glad she could not remember her dreams.

She glanced at the illuminated dial of her bedside clock and sat up, pushing her hair back from her face. She had a full day ahead of her, she reminded herself, and turning over for another doze was a luxury she couldn’t afford.

She bathed and put on her underwear, then looked along the wardrobe rail for job-hunting gear. However limited her options, she needed to make the most of them, which meant looking neat and efficient, she thought, pulling out a black skirt and another of her white cotton shirts. Both were clean, but creased, demanding a short stint at the ironing board before they presented the correct image.

Belted into her robe, she opened her door cautiously and peeped into the living room, but everything in the flat seemed quiet and completely still. And long may it remain so, Laine thought, as she trod silently on bare feet to the tall built-in kitchen cupboard where the iron was stored. Especially as it seemed Daniel now chose to sleep with his bedroom door slightly ajar for some reason and, accordingly, she needed to keep the noise level down.

Her task accomplished, she was creeping back to her room, with the freshly pressed garments over her arm, when it suddenly occurred to her that Daniel’s door was open because that was how he’d left it when he went out the previous evening.

And that could only mean.

She swallowed convulsively, the clothes crushed against her as if they were some form of defence, as she told herself that, whether he was there or not, it was none of her business. That it could not be allowed to matter to her one way or the other. And, that for her own peace of mind, it was much better not to know.

She was still telling herself all this as the door gave easily to her hand, affording her a perfect view of the empty room, and the wide, smooth bed, with its unruffled covers. Providing absolute confirmation, if it had ever been needed, that Daniel had spent the night somewhere else entirely.

So now you know, she told herself stonily. And what good has it done you?

You’re not married to him, and you never were—not in the real sense of the word. Which was your own decision. No one else’s. And you’re quite well aware that he’s not going to sleep alone just because you turned him away. You’ve been aware of it for two whole years, so you should be used to it by now.

He’s not your husband, and he never was, so it’s ludicrous to feel like this. To feel sick—hurt—betrayed, as if he’s been unfaithful to you. To allow jealousy to rip through you like a poisoned claw. To imagine him with another woman, making love, sharing with her everything that you could have had, but that you deliberately denied yourself.

She said aloud, ‘I can’t let this happen. I can’t think like this and stay sane. So I have to close myself off—to become, in effect, blind, deaf and dumb while the present situation endures.

‘And when it’s finally over, and he’s gone, I can let myself deal with it and begin to feel again. To become, at last, a whole person. ‘Somehow …’

A few hours later she had a job—although not without a certain reluctance on the part of her new employer.

‘You’re very young to be a Citi-Clean operative,’ Mrs Moss commented, looking at Laine over her glasses. ‘We usually prefer more mature ladies. Our clients are all professional people, and they demand high standards.’ She shook her head. ‘You don’t seem the type, Miss Sinclair.’

Laine gave her an equable smile. ‘I assure you, I’m quite used to hard work.’

‘Well, I’ve had two of my best girls leave recently, so I’m short-staffed at the moment. I suppose it wouldn’t hurt to give you a month’s trial,’ the older woman said grudgingly. ‘I supply uniforms, and all cleaning materials, and I don’t expect them to be wasted. Also, I’ll need two character references. I’m very strict about that. After all, most of our work is done in the absence of the client.’

She ran quickly through the wages, which were reasonable, and the hours, which were long, adding, ‘You’ll be paired with Denise—she’s one of my most experienced staff. She’ll assess you, and report back to me.’

Her gaze went down to Laine’s strapped ankle, and she pursed her lips dubiously. ‘Cleaning is physically demanding, Miss Sinclair. I hope you’re strong enough to stand up to it?’

‘A slight wrench,’ Laine told her. ‘It will be fine by Monday.’

Mrs Moss sniffed. ‘Then I’ll expect you to report here at seven thirty a.m. And I require punctuality.’

I don’t think, Laine reflected as she left the Citi-Clean office, that Mrs Moss and I are destined to be friends. But what the hell? I’m not qualified to do much else, and it’s not a lifetime commitment.

However, she promised herself, once these next difficult weeks are over, I can start to make some real plans.

She celebrated her return to the workplace by going into a small café, and treating herself to one of its massive all-day breakfasts, complete with a mountain of toast and a pot of very strong tea, courtesy of the Sinclair Rescue Fund. She’d been putting the iron away earlier when she’d suddenly remembered the old coffee jar, hidden behind the cleaning materials, where she and Jamie had kept spare cash for any domestic emergencies that might arise.

She had told herself that Jamie would almost certainly have emptied it before he left, but he must have forgotten it too, or been in too much of a hurry, because she’d found an unbelievable sixty pounds tucked away there, which, with care, would take care of her most pressing needs.

It would certainly spare her a visit to the bank, which, she recalled, biting her lip, had totally opposed her investment in the boat charter business, and advised most stringently against it. They probably wouldn’t say I told you so, but they’d almost certainly regard her as a bad risk until she could prove she’d stabilised her finances.