Полная версия

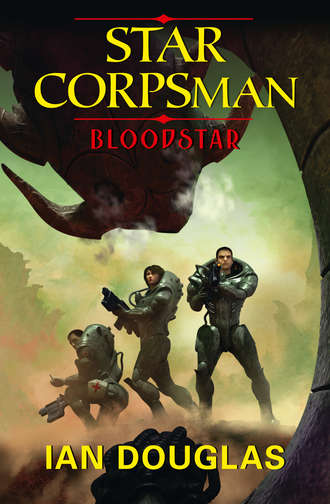

Bloodstar

On the sixth day, we folded into our Alcubierre bubble; on the seventh, we arrived at Bloodstar, 20.3 light years away.

IT LOOKS,” PRIVATE HUTCHISON SAID, “LIKE A BIG RED EYE. STARING at us.”

We were in the squad bay, looking at the image projected on the viewall bulkhead. Gliese 581, the Bloodstar, hung there in the middle of emptiness, a black-mottled orb the exact hue of arterial blood. The corona was easily visible as a pale haze surrounding the disk, as were the jets and loops of prominences extending above the rim. The surface of the disk appeared grainy, like it was made up of low-res pixels, and the starspots covered perhaps 10 percent of its face. A particularly large starspot grouping close to the center gave the impression of the jet-black pupil of a titanic, bloody eye.

And it was watching us, or so it seemed.

“This is the magnified view from the bridge, Hutch,” Gunnery Sergeant Hancock told him. “We’re still a long way out—over three AUs. Our naked eyes would see it from here as just a bright red speck.”

Gliese 581 only possessed about three tenths of Sol’s mass, so the flat metric the astrogators were always looking for went all the way in almost to the three-AU mark—3.1 to be exact—or about 464 million kilometers. The small Navy-Marine task force had emerged back into normal space hours ago, the ships shedding their excess velocity with the dissipation of the spacial torsion field. They retained a velocity of some hundreds of kilometers per second, however, as they hurtled in toward the red dwarf star. Falling tail first, they switched on their Plottel space drives and decelerated, backing down the descending slope at a steady 1 G.

Gunny Hancock thoughtclicked a display icon, and the looming image of the red dwarf dwindled into a graphic of the Gliese 581 system, the planetary orbits marked by red circles with the star at the center. Bloodstar has six planets, all of them tucked in next to their primary so tightly that the fifth planet out has an orbit closer to its sun than Mercury’s is from Earth’s, and even Niffelheim, the frigid outermost planet, is as far from Gliese 581 as Venus is from Sol.

Even from three AUs out, it was clear that the Qesh were in the Gliese 581 system in force. I could see a swarm of white points around the fourth planet out, each tagged by alphanumerics giving the object’s mass, vector, and probable identification.

I looked at the faces of the Marines around me. Most of Bravo Company was there, I thought.

The compartment was crowded. Living space on board an interstellar transport like the Clymer is pretty cramped—witness the rank upon rank of rack-tubes in the berthing compartments—but the squad bays are a lot more spacious. Well, we still call them squad bays, for tradition’s sake, but each is actually an open recreational compartment big enough to accommodate physically an entire Marine rifle company, and that’s fifty or sixty men and women. The deck can grow that many chairs for flesh-and-blood briefings, when we need them, and the viewall can project the skipper’s face for inspiring speeches, or show the tactical situation, as now, as we dropped into the Bloodstar’s inner system.

Some of those faces showed fear, some curiosity, a few a kind of smirking disdain. Most, though, had that matter-of-fact aura of professionalism I’d come to associate with the Marine Corps during the past year.

But damn, there were a lot of Qesh super-ships gathered around Salvation.

“Just how good are the Jackers, anyway?” Corporal Masserotti asked. He was one of the smirking ones.

“Good enough,” Hancock replied. “The EG puts them at type 1.165 G, with an estimated tech level twenty, and that data is from a long time ago.”

Humankind was thought to be a type 1.012 C on the Encyclopedia Galactica’s version of the Kardashev scale, with a TL of around eighteen. In other words, we had FTL and quantum power taps too, but theirs were quite a bit ahead of ours, the equivalent, possibly, of a couple of centuries. Estimating the relative technological capabilities of two mutually alien civilizations was always more guesswork than not. Differences in culture, language, and even biology could either mask or exaggerate differences. Take the T-Cets, who evolved just a few light years from Earth within the deep abyss of their world ocean. No fire, and apparently no nuts-and-bolts engineering, but they’re so far ahead of us in chemistry and biological technology that we still don’t understand more than ten percent of what we see in the Encylopedia Galactica, and attempts to communicate with them directly have consistently failed.

In warfare, a difference of only one on the tech level scale can mean a lot; think about what would happen if the atmospheric fighters from the mid-twentieth century tangled with the wood-and-fabric biplanes of just thirty years earlier.

We knew damned little about the Qesh or the nature of their technology. Their warships, though, were big, sleek, smooth-surfaced, flattened cigars comprised of domes, flutings, sponsons, and blisters that could be as much as five kilometers in length. Even the smallest were longer and more massive than the Clymer, and our intelligence people believed that all of their warships were built around powerful mass drivers that could slam twelve-ton masses into their targets with a kinetic yield equivalent to a small nuclear warhead. We didn’t know what the Qesh called their own starships. Our intel people had given them designations taken from human mythology, names like Behemoth and Leviathan, to classify them roughly by their sizes.

The graphic was totaling up the types of ships present around Bloodworld—fourteen Leviathans, eight Behemoths, twenty-one Titans, and even one Jotun.

It was a full-strength predarian warfleet.

They appeared to be dismantling the planet’s moons.

“Hawking Raiders,” Lance Corporal Benjamin Andrews said. There was just the slightest tremor behind his words. “How are we supposed to face them?”

More than two hundred years ago, no less an authority than Stephen Hawking, one of the most brilliant physicists ever to delve into cosmology, had suggested that humans might not want to make themselves known to the universe at large. According to him, an alien interstellar civilization might very well care nothing for other sapient species, but travel from star to star stripping worlds of their resources, perhaps preying on less-advanced beings. More primitive races would be unable to stand up to a sufficiently advanced technology, would be unable to stop them from extinguishing all life on the target planet.

Hawking’s warning had largely been ignored. After all, a sufficiently advanced species ought to be advanced ethically as well as technologically, right? But then we learned how to read the EG, and we started encountering some of the myriad races scattered across our part of the galaxy. We learned that each species out there was ethical within its own framework, and that those frameworks might not have room for other civilizations, or for competition. There were, we learned, entire cultures Out There that roamed the Galaxy in monster fleets, taking apart worlds for whatever they needed. Predarians, we called them. Predator barbarians.

And the name, along with “Hawking Raiders,” stuck.

“We’re not going to face them,” Hancock replied. “At least, not right away. And not directly.”

“That’s right,” Staff Sergeant Thomason added. “This is MDR. We go in quiet. We go in lethal.”

“Recon rules the night!” several voices chorused.

“Ooh-rah!” chorused some others.

I wondered how “rule the night” would apply to the Bloodworld’s twilight zone. I didn’t say anything, though. The Marines were cruising just then on pure, raw emotion.

From the look of those animated graphics on the squad bay viewall, we were hurtling tail first into a nest of hornets. The situation wasn’t quite as bad as it seemed, though, because the chances were good that they couldn’t see us. Under Plottel Drive, we were warping our own little patch of space to kill our velocity, but the effect couldn’t be detected—at least, we were pretty sure it couldn’t be detected—across more than a few tens of thousands of kilometers. Our ships had deployed their stealth screens as soon as they entered normal space. Stealth screens didn’t render a ship optically invisible, but they did drink up radar, microwave, and even long infrared. As for optical wavelengths, it’s amazing how tiny a starship is, even a ship as large as the Clymer, within a given volume of interplanetary space. The outer hull is a deep, light-drinking black, and you practically have to be on top of the ship to see her. Unless she closed to within a very few kilometers of an enemy vessel, or by very bad luck the enemy happened to notice when she occulted a star, the Clymer was damned near invisible to begin with.

So how were we able to see all of those Qesh vessels? Well, they weren’t trying to be inconspicuous, for one thing. Each one was cheerfully emitting a cacophony of microwave and infrared wavelengths, pinging one another with radar and lidar, and generally doing just about everything short of hanging out the “Welcome Earth Commonwealth” signs and setting off fireworks. Our AIs could take that data from long-range sensor scans, work out the enemy vessels’ sizes and masses, and display the distillate on the graphic projection.

In fact, I had the distinct impression that they were deliberately showing off.

“So how come the bad guys aren’t playing it safe and putting out their stealth screens?” Corporal Latimer asked. She shook her head, as if exasperated. “I mean, it doesn’t make sense. Why show us their numbers like that?”

“Yeah,” Sergeant Gibbs added. “It’s pretty freakin’ stupid if you ask me.”

“Nobody asked you, asshole,” Tomacek told him.

“It’s a fair question,” Hancock said. “And we might have a fair answer if we knew more about the bastards. Best guess is, the Jackers are supposed to be a warrior culture. Think seventeenth-century Samurai in Japan, or maybe ancient Visigoths or Huns. Hiding, sneaking around, that’s for cowards. Their culture demands that they show themselves to the enemy.”

“The art of intimidation,” I suggested.

“It’s still freakin’ stupid!”

“Uh-huh,” Hancock agreed. “But there’s something else to consider, too.”

“What’s that, Gunny?”

“What makes you think we’re seeing all of them right now?”

We all grew a bit more quiet at that as we studied the graphic.

Maybe that massive fleet we could see orbiting Gliese 581 IV was the bait.

“So,” Andrews said, “we’re outnumbered and outteched.”

“Maybe so,” Hancock said. “But we do have one important advantage.”

“Yeah, Gunny? What’s that?”

“We’re Marines.”

“That’s ay-ffirmative.” Thomason laughed. “The poor bastards’ll never know what hit ’em.”

Sometimes the sheer arrogance of the Marines amazes me.

On the other hand, maybe it’s not arrogance when it’s true.

Since Captain Samuel Nicholas recruited the first Continental Marines at Philadelphia’s Tun Tavern in 1775, the Corps has been America’s first and best line of defense. Are American interests at risk? Are American citizens threatened? Does the Army need a beachhead? Send in the Marines

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.