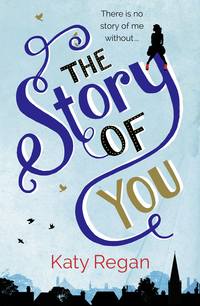

Полная версия

The Story of You

‘Come on!’ Voz was shouting from the water. ‘Sawyer, jump!’

Butler looked at Joe, then took a few steps back as if to run in – which is why I think Joe jumped the way he did, suddenly and awkwardly and not far enough out. But Butler didn’t jump, just Joe.

Beth was still talking. Your father hit the water. There was a lot of screeching, but the sun was blinding my vision. I got onto my knees to get a proper look. Then I realized that it wasn’t your dad who was screeching, because he was still under water.

There was a huge commotion and I felt this monumental surge of determination. I’d seen someone die (Mum) before my very eyes, and I wasn’t seeing it again. I ran round to that side of the quarry; your dad was surfacing on and off now, gasping for breath. Voz was trying to keep him afloat but he was struggling, shouting out. ‘He’s got his foot stuck!’ I didn’t even think this would be the first and last time I would jump off the hundred-footer, I just did it. It seemed to take forever to hit the water. I remember feeling overcome with gratitude that it was at least the water, rather than a crane or a trolley. I swam with all my might to Joe. All those years swimming for Kilterdale paid off, because I was a demon out there! Your dad was trying to keep his head up. There was wild terror in his eyes – it reminded me of a panicked horse. I dived down below. I could see his foot flailing in the murky water. He had it wrapped round some tubing – it looked like the inner of a tyre, but I couldn’t be sure. It didn’t take me long to set his foot free, then I pushed him up, me following, until we got to the sun.

It was ages till he could breathe properly again, once Voz and I had pulled him onto the rocks. He must have belly-flopped because he’d really winded himself. When I looked up, Butler was still standing at the top of the cliff, white as a sheet.

Everyone was hugging me, calling me a hero, but all I could think was: Great, the first time I get to have skin-to-skin contact with Joe Sawyer, I look like this. Do you know the first thing your father said to me, after, ‘I think you just saved my life’?

It was, ‘Did you know your hair was green?’

So, that was how I met your father. That was the start of the summer that changed everything.

As soon as I’d heard that whooshing sound that told me my message telling Joe I was coming to the funeral had gone, I’d wanted to reach inside the computer and take it back again. Now there was the four-hour journey up to Kilterdale to worry about. So much time to sit and mull.

Thankfully, the train was so packed that I spent most of the journey sitting on my bag by the Ladies’, too busy moving every time someone needed the loo to think about where I was going. I eventually got a seat at Crewe; halfway, I always think, between London and Kilterdale. The tall sash-windowed houses of London are far behind, we’ve passed the Midlands plains, and now the wet mist of the North has descended; there’s the red-brick steeples, the people with their nasal, stretchy vowels. Soon, there will be the hard towns with their hard names – Wigan Warrington – before the factories thin out into fields and sheep, and then that crescent of water, surrounded by cliffs and mossy caves. The grey-stone houses stretching back, higgledy-piggledy. The whole thing looking as if it’s about to crumble into the North Sea at any moment. Kilterdale: my home town. It’s the place I used to love like nowhere else, and now it was the place, save for the odd guilt-provoked trip, I avoided at all costs; where life for me began, and life, as I knew it, had ended, too.

I closed my eyes. At least there was one benefit of going back: I’d get to ask Dad about Mum’s ashes. Since the day we’d got them back from the crematorium, delivered to our door and so much heavier than I’d ever imagined, we’d kept them on the mantelpiece in a blue urn. Denise (evil stepmother, although not so much evil, perhaps, as hugely insecure) had gradually colonized the area: replaced the photos of us with ones of her own daughter, but the ashes had never moved. Last time I’d been home, however, they hadn’t been there. I’d asked Dad about it then and several times since but he’d always shirked an answer. This time, I decided, I couldn’t let it go.

An old man got on at Lancaster and sat next to me. He was eating his homemade sandwiches out of tin foil. I secretly watched him as he munched away, then as he brought something rustling out of the plastic bag beside him. It was a DVD. When I craned my neck, I saw it was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

‘I love horror films,’ he said, when he caught me looking – a really naughty glint in his eyes he had, too.

‘Me too,’ I told him. ‘And Texas is definitely in my top five, although I’d argue that Halloween is your ultimate classic horror. Have you seen that?’

Stan and I chatted the rest of the way home. He told me he was eighty-three and used to be a cinema usher. He’d lost his wife four months ago and slasher-horror got him through the long, lonely nights (Stan seemed completely unaware of the irony of this). He also told me he’d been a bit depressed since she’d died and was just coming back from a hospital appointment about the blackouts he’d been having.

‘I think it’s when I’ve had enough,’ he said, ‘when I miss her too much. Part of my brain just shuts down.’

Stan had a squiffy eye, so you weren’t quite sure which way he was looking, but as I looked at his good one, I said, ‘I think you put that beautifully.’

Stan was also a blessing: since I was enjoying our conversation so much, I didn’t even notice we were pulling into Kilterdale.

There was the familiar tug of guilt when I saw my dad at the end of the platform. I know he wonders why I don’t come home more. Last Christmas was special, however. Denise’s sister invited her to spend it with her in France, and so just Dad and Niamh came down to London. Niamh and I hatched this plan to go swimming in the Serpentine on Christmas morning, just as we used to go in the sea at home on Christmas Day when Mum was alive, all and sundry looking on: There they go, the nutty Kings! Amazingly, Dad said, yes – must have been still drunk from the night before – and I saw a little of my old dad that day, the hairy hulk emerging from the water, his teeth yellow against the icy blue hue of everything else, and yet the best sight ever: Bruce King and his big, wonky, yellow teeth. My dad laughing.

He wasn’t laughing now, however, standing at the other end of the platform. He looked sheepish. He often looked sheepish these days, as if he was perpetually in the doghouse, which he probably was, for leaving Denise home alone for half an hour. I’d asked him specifically to come on his own, though. There were things I wanted to talk to him about that I didn’t want to discuss once we’d set foot in Deniseville (a twisted world on a par with some of my patients’ psychotic delusions) and we were going to Mildred’s Café, like old times, for some ‘Dad and Daughter’ time.

As I walked towards him, I could see that his thick, strawberry-blond hair was combed neatly in a way he never had it when Mum was alive; when he would regularly pick us up from Brownies wearing leathers and smelling of beer. Now he was wearing red chinos, pulled slightly too high, and a linen blazer. He looked like Boris Johnson.

‘All right, Dad,’ I said. Despite the fact I spent a lot of my time disappointed with him, I couldn’t stop the rush of love I felt when I saw my dad: the pure, blood kind, not based on any kind of spiritual connection.

‘Hiya, Bobby,’ he said, and we hugged briefly as he brushed his whiskery jowl next to my cheek. ‘Journey all right?’

‘Yeah, grand.’

We walked to the car in the evening sunshine. Dad doesn’t do standing on the platform and chatting. Mum would have told you half her news before you even got to the car. ‘I see you’ve brought the weather with you, like your sister,’ he said.

‘Oh, is Niamh here?’ I said, helping Dad lift my case into the boot. This would have been a big improvement to matters. Niamh has grown up with Denise. She understands her; the atmosphere improves.

‘No, but she was, she was here with Mary last night, but they’ve gone off on one of their expeditions for the weekend. You know how those two are attached at the bloody hip,’ Dad said, slamming the boot shut. He turned to me and studied my face for a second, as if about to say something profound, then changing his mind.

‘She’ll never find herself a boyfriend, the rate she’s carrying on.’

I pictured my sister and Mary, cuddling up under the stars in their clandestine tent, and I felt like crying. I wished she’d just tell Dad. It must be a huge burden for her to carry around.

Dad patted the pockets of that beige jacket for his car keys. I stepped back to give him the once-over.

‘We might have to have a word about this little ensemble, Dad,’ I said.

He raised his bushy blond eyebrows. ‘You’re a cheeky bugger, now get in that car,’ he said. When I looked in the rear-view mirror, I saw he was smiling.

The car was spotless.

‘Just had a valet, Dad?’

‘Every Monday. Without fail,’ he said, as we turned out of the station. ‘You know how Denise likes things spick and span.’

Oh, I knew.

Dad used to drive a pick-up truck. He used to bomb around the lanes like a nutter, one tanned arm hanging out of the window, thick gold chain around his neck, smoking a café crème, us three rattling around in the back – with no seat belts – amongst the timber and the old car parts, and the paraphernalia of whatever project Dad had up his sleeve at the time. I used to hate it when people asked when I was younger: What does your dad do? Because, genuinely, I didn’t know. I longed for him to have a normal job like my friends’ dads – on the railway, or with the Gas Board, but my dad had various jobs which changed all the time, so I could never keep track. He rented boats out to fishermen in Morecambe Bay, he mended people’s cars in our back garden, he did up houses (just not our own). He had a stint as an ice-cream van driver one summer, but used to swear all the time at kids who annoyed him. ‘Oh, piss off, Johnny, you little pillock.’ Mum used to tell him off, whilst finding it hilarious. I didn’t laugh at it then, but I do now. My dad’s funny. Just not always funny ha-ha.

It’s only a five-minute drive from the station to Mildred’s Café, near the shore, but you have to go the whole length of Kilterdale, and it’s like passing through a museum of my life; where at every turn there’s a relic from my past. We pass the swimming baths, where just the whiff of chlorine means I’m ten again, flat-chested and streamlined as a dolphin – through the muffle of the water, I can hear the cheers of my parents, (in particular, my mother and her foghorn voice, which Niamh inherited): ‘C’mon, Bobby!’ as I pound towards the finish line, another medal for Kilterdale Carps.

There’s the tiny cinema where, when Niamh was a baby, Mum would drop Leah and I off for the Saturday matinee, where they’d play old films. I loved those little snippets of freedom, the times alone with my big sister. The building is dilapidated today, but I can still smell the popcorn, the fusty velvet of the seats; I can still feel the ache in my throat as I tried not to cry at E.T. in front of Leah, and the feel of my hand in her bigger one on the walk through the fields back home. I miss Leah, I think. I miss us being children together.

We pass The Fry Up, Kilterdale’s chippy, where every Friday we’d go, all five of us, Mum letting us have cans of Dr Pepper and her always having a battered sausage: ‘It’s not as if I eat like this every day of the week, is it, girls?’ she’d say, grease dripping from her chin. In the summer, we’d sit on the little bench outside, Niamh being fed chips in her pushchair – the same bench on which, years later, I’d sit with Joe eating chips, and we’d talk about our lives that were yet to unfurl, no idea of what was to become of us, what lay ahead. I savour those summers, these memories. In my mind’s eye, they’re like sunbursts, sparkling on the sea. But then, like a current dragging me under, I always come back to the summer of ’97. Those memories feel like the cool, dark waters that run beneath the sunburst-covered sea, beneath everything I do.

We had to go down Friars Lanes. Due to the early warm weather, the hedgerows were high and bursting with green shoots; the fields, brown and cloggy with mud in the winter, were speckled with green. If you looked up, the trees were smudged with birds’ nests. They looked like masses of black thread.

I could feel Dad looking at me. ‘So,’ he said, eventually. ‘Why are you going to this funeral?’

He rarely spoke so directly and I started, found myself feeling defensive.

‘I don’t know, ’cause it’s his mum and it would be nice to support him. Because Marion was so good to me when my mum died?’

Dad nodded slowly and looked at me with this sad smile.

‘What?’ I said.

‘Nothing, it’s just …’ He paused for what seemed ages. ‘I thought you’d left all that behind, Robyn …’

‘I have.’

‘So …’

I tried to look at the fields, the copses beyond, not at the lanes unfolding in front of us.

‘So, what?’

‘So, I’m worried about you, that’s all. I’m just being concerned Dad.’

I was touched he was being concerned Dad.

‘It’s just the service and a few sandwiches back at the vicarage,’ I said. ‘And anyway, it was an excuse to see you.’ I reached over and touched him on his shoulder. He flinched, just ever so slightly, but he did, I felt it.

‘Okay, well that’s all right then.’

‘Dad, I’m thirty-two,’ I said. ‘I’ll be fine.’

He patted my knee and smiled. ‘And you’re still my little girl,’ he said.

Silence descended. It was thick and sticky and I didn’t know how to move it.

Dad spoke, eventually, changing the subject: ‘Look at them fields, eh, Robyn? Absolutely marvellous. I bet you miss all this in London, don’t you?’

I wish I did. I wish coming back was like therapy for me, like going back home was therapy for other people.

‘Yeah, not many cow-pats in Archway,’ I said. I kept looking out of the window, so he couldn’t see my eyes water.

I was glad once we’d got to Mildred’s. There was something about travelling in a car with Dad these days that was intense, what with the elephant squeezed in there with us.

We sat at our usual table at the back and ordered the same thing we ordered when Mum was alive: me a cappuccino and a millionaire’s shortbread, Dad a cup of tea and a teacake. Mum used to have a banana milkshake with cream on top and a herbal tea. She thought the latter cancelled out the former. She was a bit deluded like that. It’s probably why she thought three Rothmans a day couldn’t hurt anyone, and maybe they didn’t, who knows? Maybe the Rothmans had nothing to do with it.

Dad pulled up his red trousers, sat down and searched my face.

‘Bloody Nora, you look more like your mother every time I see you. Same beautiful smile.’ His eyes still welled up when he mentioned her.

‘Thank God, eh, Dad? I lucked out, gene-wise.’

‘Yep, you got your mother’s looks. Niamh is more of a King, I think, and Leah, well …’

The teacake had arrived.

‘Have you spoken to her, Dad?’

Dad made sure every millimetre of that teacake had butter on.

‘No, I haven’t managed to yet.’

‘But you know how upset Mum would be if she knew you two hardly spoke.’

‘She’s never in, I’ve tried lots of times.’ I was kind of disappointed he felt he could just lie like that.

‘Dad, Leah hardly ever goes out in the evenings any more, you know what she’s like about leaving the kids.’ He looked up. ‘Okay, you don’t, but I’m telling you, she’s paranoid, especially about Jack and his asthma. She had to take him to A&E the other night.’

Dad had picked up the teacake but put it down again. His whole face sort of slid.

‘Did she?’

‘Yes.’

A blackbird appeared at the window. It sounds ridiculous, but I sometimes liked to imagine it was Mum when things like that happened, checking in on us. I felt like she was urging me to get to the point.

‘Dad, also, about the ashes,’ I said. ‘Please can I have them? I’ve been asking for over a year now.’

‘Well, it’d help if we saw more of you. There’s only Niamh that comes to see us.’

Thank God for Niamh, I thought. I hated what had happened, but most of all I hated what it had done to my relationship with my father, with my home town. As a family, we used to be so close.

‘Anyway, I’ve got some news,’ he said, changing the subject. Dad never had news. ‘Denise and I – well, I … am selling the house. We’re going to move to somewhere smaller. It’s too much for Denise to clean.’

That blackbird flew off then, presumably to have a good snigger.

Weirdly, I didn’t feel emotional about them moving out of the house we all grew up in; it hasn’t been ‘our’ house since Denise moved in, four months after Mum died, anyway, and magnolia-d the living daylights out of it.

‘That’s great news, Dad,’ I said. ‘So when might this be?’

‘We’ve put an offer in on a place in Saltmarsh, so all being well … a couple of months?’

I smiled. ‘I’m pleased for you, Dad,’ I said, and I was. Staying in that house with all the memories of Mum had affected him more than he let on, and whatever I felt about Denise, I couldn’t bear Dad to feel sad. ‘It’ll be good, a new start.’ He looked pleased I’d taken the news so well.

‘So, Mum’s ashes then,’ I continued – he wasn’t changing the subject that easily. ‘All the more reason for me to have them. Mum would hate to be in any house but that one. She loved that house.’

I tried to imagine Mum being happy in a dormer bungalow in Saltmarsh when she was alive, and struggled.

‘I know, I know.’

‘Even if she never got her new kitchen.’

Dad laughed, then sniffed, his eyes misting over again.

‘Also, when are you going to call Leah?’ I said, patting his hand. ‘Because surely this is the perfect opportunity for you two to stop being so ridiculous? The funeral was sixteen years ago.’

He sighed. You conned me into thinking this was a nice cup of tea with my daughter and you planned this all along.

‘I will, okay? Just don’t bloody hassle me, Robyn,’ he said. ‘You know how I hate to be hassled.’

‘Yeah, I know, I’m sorry.’

I feared I’d overstepped the mark; rocked what was turning into the first proper, one-to-one chat with my dad for over a year, and was eager to rein things back, but then Dad looked up and his whole face lit up. ‘Oh, here she is,’ he said, smiling at someone behind me. The scent of Elnett reached me before I even turned around, to see Denise walking towards us – her jet-black hair sprayed stiff, the lashings of silver eye shadow right up to her brows, and that look in her eyes already: This IS a competition and I shall win.

I looked back to Dad. I wanted him to see my face, how annoyed I was that he’d clearly invited her, but he’d already got up and was getting his wallet out. ‘What do you want, love? I’ll get it.’

Chapter Five

I timed my arrival at the church to avoid the bit where everyone mingles outside before they go in. I’ve never liked that part. I can still remember to this day, outside this same church, the humiliation of having to face my six-foot, surf-dude cousin, Nathan, whilst I was a blotchy, snotty wreck at my own mother’s funeral. All the embarrassing hugs from people I didn’t know. I was glad Joe was spared that part too, because he was carrying the coffin. I walked up the path of St Bart’s, just as they were taking it out of the hearse. It was pale oak against the vivid blue sky, with a waterfall of peach roses on top (I was right about those).

There was the crunch of shoes on gravel. Someone cried ‘one, two, three’ as it was lifted onto the shoulders of six men. I recognized Joe straight away, of course; at the back, one trouser leg stuck in his sock, a look of such gritty determination on his face, as if he were about to charge through the stained-glass window of the church and deliver her to the gates of heaven himself. I recognized every single one of the five other pallbearers too: Joe’s uncle Fred at the front. Peg-leg Uncle Fred, Joe used to call him, Joe being one of those people who could get away with insulting people to their face. On the other side of him was Mr Potts, still with his extraordinary eyebrows. Mr Potts would often be sitting at the vicarage kitchen table when you went round, talking really animatedly as his caterpillar eyebrows did Mexican waves across his forehead. Joe and I used to debate how differently Potty’s life could have turned out, if only he’d trimmed those eyebrows. So simple! He could have had a wife by now. Behind him was Ethan, Joe’s youngest brother, and then at the back, his other brothers, Rory and Simon, and then Joe. Joe’s dad was at the front of it, all in his black funeral regalia. So he’d made it. But then, as if the Reverend Clifford Sawyer was going to let any other rev guide his beloved Marion on her final journey to the gates of Paradise.

I gave the coffin a wide berth and joined everyone else in the churchyard. Half of Kilterdale was there. Side on, you could see how all four Sawyer brothers had the same profile: long face, these big, deep-set doe eyes and a slightly beaky nose; all put together it was somehow very handsome. Ethan has Down’s syndrome, so his features are obviously a little different, but they all have the same hair: light brown, with a hint of red, and so fine and straight you never have to brush it.

People’s conversations tapered to a murmur and then that awful, sombre silence as they parted to make way for Marion’s last journey.

The plan was, I’d slip in at the back, say a quick ‘Hi’ to Joe at the end of the service, then slip out again, unnoticed. I found a place on the back pew and kept a low profile, leafing through the Order of Service. The first, magical, angelic notes of ‘In Paradisum’ from Fauré’s Requiem struck up just as they brought her in. Then, it was unbelievable: the whole place was illuminated by a freak beam of sunlight coming smack-bang from between Jesus’s thighs, on the far right window. It really was like heaven in there – and I wished, not for the first time, that I was a believer. But then perhaps when you work with people who try to recruit disciples in Morrison’s, you start to equate religion with madness.

A cough echoed around the cool caverns of the church. Some kid goes, ‘Daddy, you’re funny,’ just as Marion was lowered onto the trestle. Joe’s dad stood at the feet end, palms pressed together. ‘Well,’ he said, gesturing to the beam of sunlight, ‘she’s here, ladies and gentlemen.’ And everyone laughed and shed a tear at the same time, including me.

The service was lovely. I know people always say that, but I feel I can comment with sincerity, since I’ve been to a few not-so-lovely ones in my time, including my own mother’s. Joe’s dad told funny stories: how Marion was working behind her parents’ shrimp bar on Morecambe front when they met, but that even the ever-present whiff of cockles couldn’t keep him away, such was her luminescent beauty.

Occasionally, during the hymns, I looked over at Joe’s pew. Rory and Simon were grim but dry-eyed, Ethan looked confused as to where we were on the Order of Service, but I decided Ethan was probably fine, in Ethan’s own world. Joe was on the end, crying his eyes out, wiping the snot and the tears on the back of his hand because Joe wouldn’t think to bring such a banal item as a packet of tissues. And although I knew the pain he was feeling, I also thought: Good for you, Joe. Him being such an open book was always the thing I loved about him. In fact, when I look back to that time, I can probably remember Joe crying more than me.

It was such a warm day that they’d left the door open, and so if I looked to the left, down the hill on top of which the church teetered, and past the crumbly tombstones, I could see the sea, springing up the glossy, black rocks; the same sea Joe and I had played in as loved-up teenagers, and it comforted me for some reason. Here we were, in this church, half on land, half looking like it might slip away into the sea at any time. This was all so momentary; we were all just passing through, liable to drop off the end of the world at any given time.