Полная версия

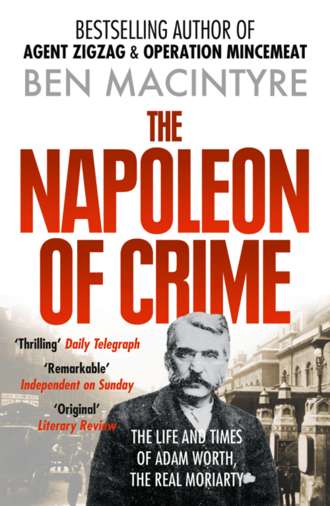

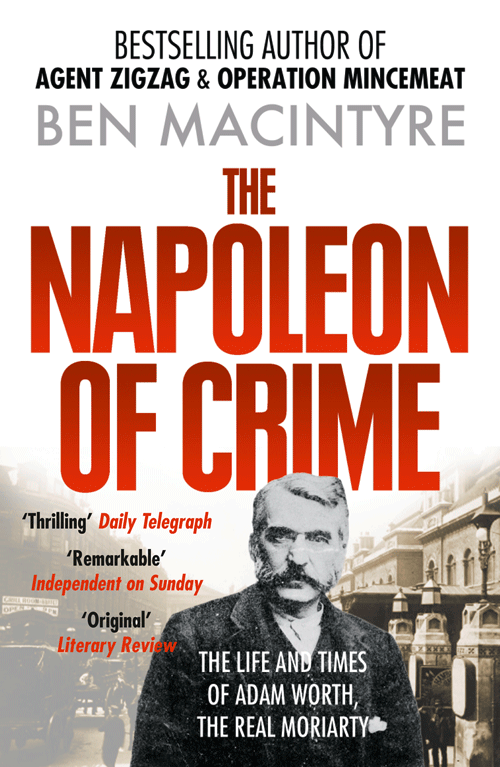

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

The Napoleon of Crime

The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

Ben Macintyre

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Ben Macintyre 1997

Ben Macintyre asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006550624

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2012 ISBN: 9780007383641

Version: 2017-02-20

FOR KATE

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

The Elopement

A Fine War

The Manhattan Mob

The Professionals

The Robbers’ Bride

An American Bar in Paris

The Duchess

Dr Jekyll and Mr Worth

Cold Turkey

A Great Lady Holds a Reception

A Courtship and a Kidnapping

A Wanted Woman

My Fair Lady

Kitty Flynn, Society Queen

Dishonour Among Thieves

Rough Diamonds

A Silk Glove Man

Bootless Footpads

Worth’s Waterloo

The Trial

Gentleman in Chains

Le Brigand International

Alias Moriarty

Atonement

Moriarty Confesses to Holmes

The Bellboy’s Burden

Pierpont Morgan, the Napoleon of Wall Street

Return of the Prodigal Duchess

Nemo’s Grave

EPILOGUE: The Inheritors

Keep Reading

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Preface

I had come to Los Angeles to cover the latest instalment in the Rodney King case, that grimly defining saga of modern times. But I left the city with a very different tale of cops and robbers.

The white Los Angeles policemen who had been filmed by an amateur cameraman beating up a black motorist were in the dock for a second time, stolidly proclaiming their innocence. It was confidently predicted that the city was on the verge of another riot. One afternoon, when the jury had retired to consider its verdict, I decided to drive out to the suburb of Van Nuys to explore the archives of the Pinkerton’s Detective Agency, thinking I might write an article for The Times about American law enforcement in another, sepia-tinted age, a world away from the thugs on trial downtown, or those in the ghetto who might take to the streets if they escaped justice again.

The Pinkertons. The name itself summoned up hard lawmen with comic facial hair and six-shooters, riding out after the likes of Jesse James, the Reno gang, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Shown into the basement archive by a bored secretary popping bubble gum, I immediately realized there was far more here than could possibly be digested in a year, let alone an afternoon. The rows of cabinets literally overflowed with files, a testament to the painstaking methods of America’s earliest detectives. After an hour or so of random delving, I picked up a bound scrapbook, dated 1902. Leafing through it, I came across this fragment of newsprint:

SUNDAY OREGONIAN, PORTLAND, JULY 27, 1902.

ADAM WORTH, GREATEST THIEF OF MODERN TIMES; STOLE $3,000,000

THIS is the story of Adam Worth.

If a fiction writer could conceive such a story, he might well hesitate to write it for fear of being accused of using the wildly improbable.

The sober, cold, technical judgment passed upon Adam Worth by the greatest thief-hunters of America and Great Britain is that he was the most remarkable, most successful and most dangerous professional criminal ever known to modern times.

Adam Worth, in a life of crime covering almost half a century, looted at least $2,000,000, and most probably as much as $3,000,000.

He cruised through the Mediterranean on a steam yacht with a crew of 20 men, and left a trail of looted cities behind him.

He was caught only once, and then through a blunder by a stupid confederate.

He ruled the shrewdest criminals, and planned deeds for them with craft that bade defiance to the best detective talent in the world.

The police of America and Europe were eager to take him for years, and for years he perpetrated every form of theft – check-forging, swindling, larceny, safe-cracking, diamond robbery, mail robbery, burglary of every degree, ‘hold-ups’ on the road and bank robbery – under their very noses with complete immunity.

There were three redeeming features in the life of this lost human creature.

He worshiped his family and regarded and treated his loved ones as something sacred. His wife never knew that he was a criminal. His children are living in the United States today in complete ignorance of the fact that their father was the master-thief of the civilized world.

He never was guilty of violence, and would have nothing to do under any circumstances with any one who did.

He never forsook a friend or accomplice.

Because of that loyalty he once rescued his band of forgers from a Turkish prison and then from Greek brigands, reducing himself to beggary to do it.

Because of that loyalty he became ‘The Man Who Stole the Gainsborough.’

The reason for that theft will be told here for the first time. Until now, all who knew it were under binding obligations of silence. The motive that caused the deed was unique in the history of modern crime.

And Adam Worth, who had millions, who once flipped coins for £100 a toss, who at one time had an interest in a racing stable, had a steam yacht and a fast sailing yacht, died a few weeks ago as he had begun – a poor, penniless thief.

He towered above all other criminals of his time; he was so far in advance of them that the man who hunted him weakened before his masterful intellect; but the inexorable fate that pursues the breaker of moral law caught him and finished him at last where the man-made law was powerless.

When Adam Worth died he was as much a mystery – aside from certain officials and detective inspectors of Scotland Yard, the Pinkertons, and a very few American police officials – even to the great majority of the police officials of the world as he had been throughout his life. If he had not become prominent recently as the man who stole and returned the Gainsborough portrait, the public probably never would have heard of him at all. Only a very few of the most able detectives of the world knew him even by sight. Still less knew anything about him. The story that follows is an absolute and minutely exact history, verified in every particular and vouched for by the men who spent almost half a century in trying to hunt him down.

Nothing in this history is left to conjecture.

The rest of the promised article, infuriatingly, had not been pasted into the book. Time and again I read this clipping, extravagant in its claims even by the journalistic standards of the day, and a small LA riot of excitement began building somewhere in the back of my mind. Then my electronic pager sounded, bringing me hurtling back to the present with the news that a verdict in the Rodney King trial was imminent. By the next afternoon, two of the cops had been found guilty, the inhabitants of South Central Los Angeles had obligingly decided not to go on the rampage, and I was back in Van Nuys, combing the Pinkerton archive for every scrap of material I could find on Adam Worth. The detectives, I soon learned, had hunted Worth across the world for decades with dogged perseverance, and the result was a wealth of documentation: six complete chronological folders, tied together with string and bulging with photographs, letters, more newspaper articles and hundreds of memos by the Pinkerton detectives, each one written in meticulous copper-plate and relating a tale even more intriguing and peculiar than the nameless Sunday Oregonian writer had implied.

For Adam Worth, it transpired, was far more than simply a talented crook. A professional charlatan, he was that most feared of Victorian bogeymen: the double-man, the charming rascal, the respectable and civilized Dr Jekyll by day whose villainy emerged only under cover of night. Worth made a myth of his own life, building a thick smokescreen of wealth and possessions to cover a multitude of crimes that had started with picking pockets and desertion and later expanded to include safe-cracking on an industrial scale, international forgery, jewel theft and highway robbery. The Worth dossiers revealed a vivid rogues’ gallery of crooks, aristocrats, con men, molls, mobsters and policemen, all revolving around this singular man. In minute detail, the detectives described his criminal network, radiating out of Paris and London and stretching from Jamaica to South Africa, from America to Turkey.

I left the Pinkerton archive elated but tantalized. The material was vast but incomplete. Like any sensible crook anxious to avoid detection, Worth had not written his memoirs and had left behind only a handful of coded letters. My initial researches had raised more questions than they answered. How had Worth evolved his contradictory moral code? How had he escaped capture for so many years? How had he transformed himself from a penniless German-Jewish emigrant from Cambridge, Massachusetts, into an English milord in the aristocratic heart of London?

One mystery intrigued me more than all the others. In the early summer of 1876, at the height of his criminal powers, Worth stole from a London art gallery in the dead of night The Duchess of Devonshire, Thomas Gainsborough’s famous portrait and then the most expensive painting ever sold. What had possessed him? And why, still more bizarrely, had he kept the great painting, in secret, for the next twenty-five years? The Gainsborough portrait, I was already certain, held the key to unlocking the secret of Adam Worth.

California proved to be only the first stop on a long trail. Slowly I assembled a fuller picture, from letters, diaries, published memoirs by other criminals, newspaper accounts and the archives of Scotland Yard, the Paris Sûreté, Agnew’s art gallery and Chatsworth House. Other, quite unexpected discoveries, soon followed.

Worth invented his own life as a dramatic romance. But when the Sunday Oregonian talked of his piquant history as the very stuff of fiction, the newspaper was telling the literal truth. The English detective Sherlock Holmes was already a household name when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first learned of Worth’s villainous deeds. The great English writer, it turns out, had used Worth as the model for none other than Professor Moriarty, Holmes’s evil, art-collecting adversary and one of the most memorable criminals in literature. Conan Doyle was not alone in his debt to Worth, for writers as diverse as Henry James and Rosamund De Zeer Marshall, an author of wartime bodice-rippers, also found inspiration in Worth’s activities.

My quarry led me on some unlikely pilgrimages: to the grand building in Piccadilly near Fortnum & Mason’s that was Worth’s criminal headquarters; to the Civil War battlefield where he first reinvented himself; to the London art gallery where he stole his most prized possession and to a room in Sotheby’s auction house where, for the first time, I encountered that indelible image face to face. As I write, from the Paris office of The Times, I can look across the Place de l’Opéra to the Grand Hotel, where Worth ran an illegal casino and held court with his mistress in the 1870s. I am still not sure whether I have been following Worth for the last four years, or whether he has been shadowing me.

I had set off to hunt down ‘The Greatest Thief of Modern Times’. What I found turned out to be an unlikely reflection of those times, and our own: a Victorian gentleman and master thief who merged the highest moral principles with the lowest criminal cunning. What follows is a story that has never been told before; it is a story of dual personalities, double standards and heroic hypocrisy.

This is the story of Adam Worth.

Paris

March, 1997

‘Adam Worth was the Napoleon of the criminal world. None other could hold a candle to him.’

SIR ROBERT ANDERSON, Head of Criminal Investigation, Scotland Yard, 1907

‘He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider at the centre of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized … the central power which uses the agent is never caught—never so much as suspected.’

SHERLOCK HOLMES on Professor Moriarty in ‘The Final Problem’ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

‘I hope you have not been leading a double life, pretending to be wicked and being really good all the time. That would be hypocrisy.’

OSCAR WILDE, The Importance of Being Earnest

£1000

R E W A R D.

STOLEN

Between half-past nine p.m. 25th, and 7 a.m. 26th inst, from the Picture Gallery, No. 39b, Old Bond Street, the celebrated Oil Painting, by Gainsborough, of the Duchess of Devonshire, Size 60 inches by 45 inches, without frame or stretcher.

The above Reward will be paid by Messrs. Agnew and Sons, No. 39b, Old Bond Street, to any person giving such information as will lead to the apprehension and conviction of the thief or thieves, and recovery of the painting.

Information to Superintendent Williamson, Detective Department, Great Scotland Yard, London, S.W.

ONE

The Elopement

ON A MISTY MAY MIDNIGHT in the year 1876, three men emerged from a fashionable address in Piccadilly with top hats on their heads, money in their pockets and burglary, on a grand scale, on their minds. At a deliberate pace the trio headed along the empty thoroughfare and at the point where Piccadilly intersects with Old Bond Street, they came to a stop. Famed for its art galleries and antiques shops, Old Bond Street by day was choked with the carriages of the wealthy, the well-bred and the culturally well-informed. Now it was quite deserted.

The three men exchanged a few words at the corner of the street before one slipped into a doorway, invisible beyond the dancing gaslight shadows, while the other two turned right into Old Bond Street. They made an incongruous pair as they walked on: one was slight and dapper, of some thirty-five years in age, with long, clipped moustaches and dressed in the height of modern elegance, complete with pearl buttons and gold watch-chain. The other, ambling a few paces behind, was a towering fellow with grizzled mutton-chop whiskers, whose ill-fitting frock coat barely contained a barrel chest. Had anyone been there to observe the couple, they might have assumed them to be a rich man taking the night air with his unprepossessing valet after a substantial dinner at his club.

Outside the art gallery of Thomas Agnew & Sons, at 39 Old Bond Street, the two men paused and while the aristocrat extinguished his cheroot and admired his own faint but stylish reflection in the glass, his brutish companion glanced furtively up and down the street. Then, at a word from his master, the giant flattened himself against the wall and joined his hands in a stirrup, into which the smaller man placed a well-shod foot, for all the world as if he were climbing onto a thoroughbred. With a grunt the big man heaved the little fellow up the wall and in a moment he had scrambled nimbly onto the window ledge some fifteen feet above the pavement. Balancing precariously, he whipped out a small crowbar, wrenched open the casement window and slipped inside, as his companion vanished from sight beneath the gallery portal.

The room was unfurnished and unlit, but by the faint glow from the pavement gaslight a large painting in a gilt frame could be discerned on the opposite wall. The little man removed his hat as he drew closer.

The woman in the portrait, already famed throughout London as the most exquisite beauty ever to grace a canvas, gazed down with an imperious and inquisitive eye. Curls cascaded from beneath a broad-brimmed hat, set at a rakish angle to frame a painted glance at once beckoning and mocking, and a smile just one quiver short of a full pout.

The faint rumble of a night-watchman’s snores wafted up from the room below, as the little gentleman unclipped a thick velvet rope that held the inquisitive public back from the painting during daylight hours. Extracting a sharp blade from his pocket, with infinite care he cut the portrait from its frame and laid it on the gallery floor. From his coat he took a small pot of paste and, using the tasselled end of the velvet rope, he daubed the back of the canvas to make it supple and then rolled it up with the paint facing outwards to avoid cracking the surface, before slipping it inside his frock coat.

A few seconds later he had scrambled back down his monstrous assistant to the street below. A low whistle summoned the lookout from his street corner, and with jaunty step the little dandy set off back down Piccadilly, the stolen portrait pressed to his breast and his two rascally companions trailing behind.

The painted lady was Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, once celebrated as the fairest and wickedest woman in Georgian England. The painter was the great Thomas Gainsborough, who had executed this, one of his greatest portraits, around 1787. A few weeks before the events just recounted, the painting had been sold at auction for ten thousand guineas, at that time the highest price ever paid for a work of art, causing a sensation. Georgiana of Devonshire, nee Spencer, was once again the talk of London, much as her great-great-great grandniece Diana, Princess of Wales, nee Spencer, would become in our age.

During Georgiana’s lifetime, which ended in 1806, her admirers vied to pay tribute to ‘the amenity and graces of her deportment, her irresistible manners, and the seduction of her society’. Her detractors, however, considered her a shameless harpy, a gambler, a drunk and a threat to civilized morals who openly lived in a ménage à trois with her husband and his mistress. No woman of the time aroused more envy, or provoked more gossip.

The sale of Gainsborough’s great painting to the art dealer William Agnew had been the occasion for a fresh burst of Georgiana-mania. Gainsborough’s vision of enigmatic loveliness, and the extraordinary value now attached to it, became the talk of London. Victorian commentators, like their eighteenth-century predecessors, heaped praise once more on this icon of female beauty, while rehearsing some of the fruitier aspects of her sexual history.

When the painting was stolen, the public interest in Gainsborough’s Duchess reached fever-pitch. The painting acquired huge cultural and sexual symbolism. It was praised, reproduced and parodied time and again, the Marilyn Monroe poster of its day, while Georgiana herself was again held up as the ultimate symbol of feminine coquetry. The name of the man who kidnapped the Duchess that night in 1876 was Adam Worth, alias Henry J. Raymond, wealthy resident of Mayfair, sporting gentleman about town and criminal mastermind. At the time of the theft Worth was at the peak of his powers, controlling a small army of lesser felons in an astonishing criminal industry. Stealing the picture was an act of larceny, but also one of hubris and romance. Georgiana and her portrait represented the very pinnacle of English high society. Worth, by contrast, was a German-born Jew raised in abject poverty in America who, through an unbroken record of crime, had assembled the trappings of English privilege and status, and every appearance of virtue. The grand duchess had died seventy years before Worth decided, in his own words, to ‘elope’ with her portrait, beginning a strange, true Victorian love-affair between a crook and a canvas.

TWO

A Fine War

FOURTEEN YEARS EARLIER, at the end of August 1862, the armies of the Union and the Confederacy had come to grips in a muddy Virginia field and blasted away at each other for two days in an encounter known to history as the Second Battle of Bull Run, one of the very bloodiest engagements of the American Civil War.

According to official war records, more than three thousand soldiers died in that carnage including one Adam Worth, who was just eighteen at the time.

Bull Run was the scene of Worth’s first death and first reincarnation. Reports of his death were, of course, greatly exaggerated and so far from perishing on the Virginia battlefields, the young Worth had survived the war in excellent health with a changed name, a deep aversion to bloodshed and a wholly new career as an impostor stretching out before him. The Civil War almost destroyed America, but after the bloodletting the country fashioned itself anew, and so did Worth. Over the next forty years he would vanish and then reappear under a new name with a regularity and ease that baffled the police of three continents.