Полная версия

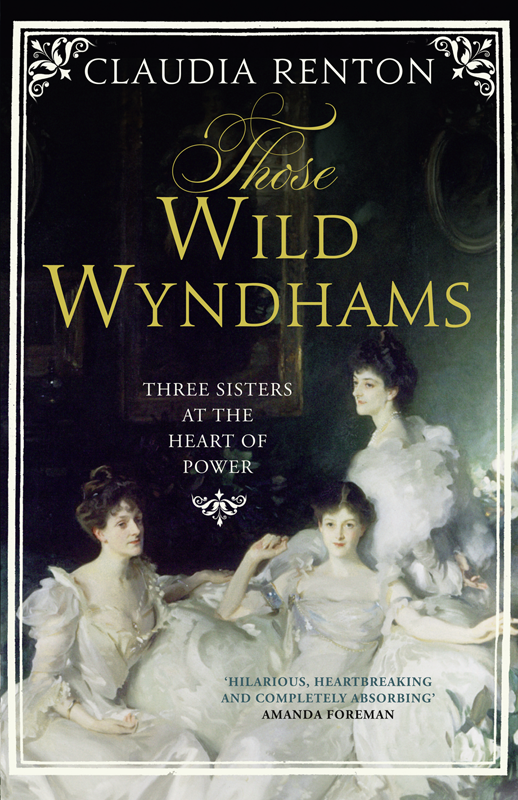

Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power

Dedication

For Mama.

Always.

Epigraph

‘La Chanson de Marie-des-Anges’

Y avait un’fois un pauv’gas,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Y avait un’fois un pauv’gas,

Qu’aimait cell’qui n’l’aimait pas.

Elle lui dit: Apport’moi d’main

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Elle lui dit: Apport’moi d’main

L’cœur de ta mèr’ pour mon chien.

Va chez sa mère et la tu

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Va chez sa mère et la tue,

Lui prit l’cœur et s’en courut.

Comme il courait, il tomba,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Comme il courait, il tomba,

Et par terre l’cœur roula.

Et pendant que l’cœur roulait,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Et pendant que l’cœur roulait,

Entendit l’cœur qui parlait.

Et l’cœur lui dit en pleurant,

Et lon la laire,

Et lon lan la,

Et l’cœur lui dit en pleurant:

T’es-tu fait mal mon enfant?

Jean Richepin (1848–1926)

‘Do you know Richepin’s poem about a Mother’s Heart? It means something like this:- “there was a poor wretch who loved a woman who would not love him. She asked him for his Mother’s heart, so he killed his Mother to cut out her heart and hurried off with it to his love. He ran so fast that he tripped and fell, and the heart rolled away. As it rolled it began to speak and asked “Darling child, have you hurt yourself?”’

George Wyndham to Pamela Tennant, 11 March 1912

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

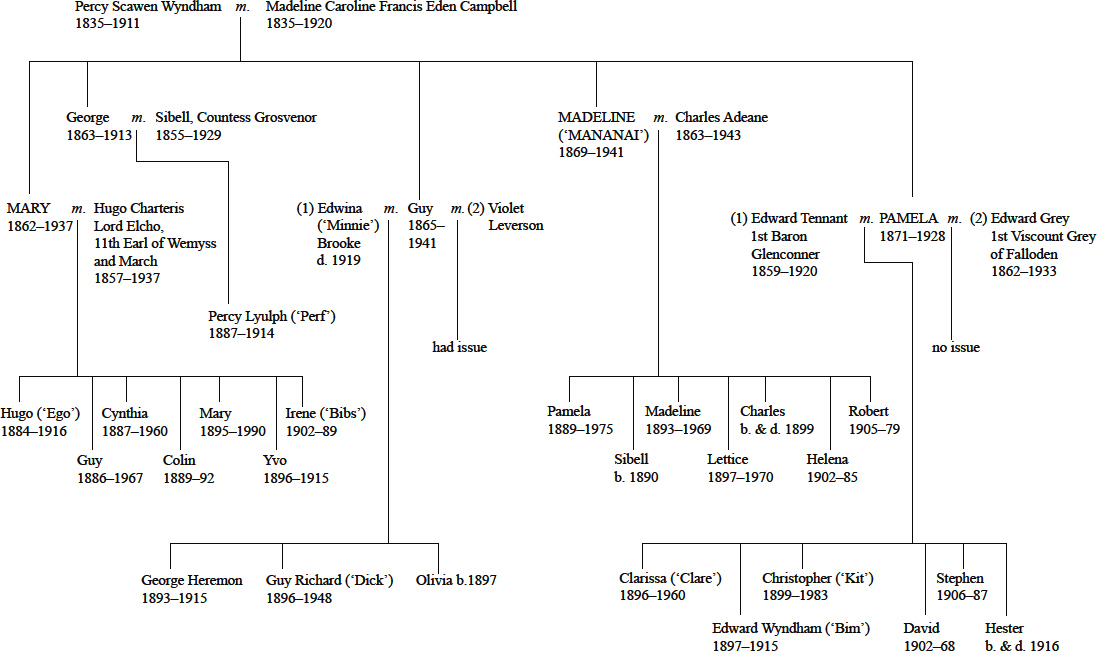

Family Tree

Prologue

1. ‘Worse than 100 boys’

2. Wilbury

3. ‘The Little Hunter’

4. Honeymoon

5. The Gang

6. Clouds

7. The Birth of the Souls

8. The Summer of 1887

9. Mananai

10. Conflagration

11. The Season of 1889

12. The Mad and their Keepers

13. Crisis

14. India

15. Rumour

16. Egypt

17. The Florentine Drama

18. Glen

19. The Portrait, War and Death

20. Plucking Triumph from Disaster

21. The 1900 Election

22. Growing Families

23. The Souls in Power

24. Pamela at Wilsford

25. Mr Balfour’s Poodle

26. 1910

27. Revolution?

28. 1911–1914

29. MCMXIV

30. The Front

31. The Remainder

32. The Grey Dawn

33. The End

Picture Section

List of Illustrations

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

On a cool February night in 1900, Pamela Tennant, wife of the industrialist Eddy Tennant, was dining at the London townhouse of her brother and sister-in-law, Lord and Lady Ribblesdale. The Season had not quite started, but there was already a smattering of balls. By early summer that smattering would become a deluge, as seemingly every house in Mayfair echoed to the strains of bands and England’s elite waltzed round and round camellia-filled ballrooms in what would prove to be the last year of Victoria’s reign. Thus far, London seemed to have escaped the disgusting yellow smog that had blanketed the city for months the year before, and added to the misery of the swathes affected by a bad strain of influenza that year.

Pamela was not really looking forward to the Season that was to come: or to any Season, for that matter. In the five years since she had married, her refusal to play ball socially had provoked several spats with her sister-in-law. Charty Ribblesdale, one of the audacious Tennant sisters who had launched themselves on to London Society twenty years before, could not understand why Pamela should wilfully clam up when faced with new people. Pamela’s refusal to play by any rules but her own mystified Charty and her sisters Margot and Lucy. They thought it alien to the ethos of the Souls: their fascinating, chattering set who affected insouciant, swan-like ease, no matter how frantically their legs paddled beneath the serene surface.

The delightfully haphazard Mary Elcho, Pamela’s eldest sister, was a leading light of the Souls. Pamela, beautiful, brilliant, a master of the pointed phrase, had it in her to joust with the best of them. But she chose not to. Instead, she professed disdain for ‘those murdered Summers’ of the Season, and openly expressed her preference for Wiltshire, where she caravanned across the Downs in the company of her children.1 It was a very peculiar attitude.

The burly American placed next to Pamela also seemed ill at ease among Society’s hubbub. John Singer Sargent, whose Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose had dazzled the Royal Academy over a decade before, was establishing himself as a society portraitist par excellence, but he had little time for his sitters’ chatter. He preferred quiet times in the Gloucestershire village of Broadway with his sisters and nieces – incidentally not far from where Mary Elcho lived at Stanway. ‘He was very nice & simple, & … very shy & not the least like an American,’ Mary’s friend Frances Horner reported to the artist Edward Burne-Jones after meeting Sargent (for Sargent, although an American by parentage, had been born and raised on the Continent), ‘& he wasn’t very like an artist either! … he hated discussing all his great friends … & talking about his pictures.’2

Perhaps Charty took a certain pleasure in seating Pamela next to Sargent that evening. A taste of her own medicine – and Charty could justify the placement because Sargent was currently working on a portrait of Pamela and her sisters. It had been commissioned by their father, Percy Wyndham, who, with his wife Madeline, had built Clouds in Wiltshire, a house little over a decade old and already famous as a ‘palace of weekending’.3 Pamela, Mary and sweet-natured Madeline Adeane (who so unluckily after a whole brood of girls had finally succeeded in giving birth to a boy only for the premature infant to die the same day) had been sitting to Sargent ever since then.

There was plenty to talk about. No mention was made of the Boer War’s disastrous progress, or Pamela’s elder brother George, Under-Secretary in the War Office, whose triumphant speech in the House of Commons a few weeks before had singlehandedly seemed to redeem the Government’s conduct of the war. All Sargent’s talk was of the portrait. The first sittings had taken place over a year before, in the drawing room of the Wyndhams’ London house, 44 Belgrave Square. Yet just recently, Pamela, in the thick of preparations for one of the tableaux of which she was so fond, received a letter from Percy suggesting that Sargent’s portrait might still not be finished in time for this year’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. What with the uncertain light at this time of year, and the fact that the Wyndhams would not be in London until after Easter, ‘perhaps this is better’, he concluded.4 To Pamela’s mind, this was not better. At this rate, she replied ominously, there was the danger that ‘we shall all be old and haggard before the public sees it’.5

Pamela in the flesh made the shortcomings of Pamela in oils all too clear. Sargent told Pamela in his deep, curiously accentless voice (the legacy of his Continental upbringing) that he ‘felt sure’ that Mr Wyndham ‘would not mean it to be as it is’. ‘He is very anxious for some more sittings from me and enquired my plans most pertinaciously,’ Pamela told Percy the next day. Her very presence had seemed to prove an inspiration: ‘“and now I see you oh it must be worked on” – squirming & writhing in his evening suit – “no finish – no finish” – he got quite excited’.6

As agreed, Pamela made her way to Sargent’s studio on Tite Street in Chelsea at half-past two the following Saturday. Three or four days was all that Sargent, a phenomenally fast worker, required before she could thankfully flee London once again. ‘He has not repainted the face … He worked on little corners of it and has much improved it I think,’ Pamela said. He had remodelled her nose, taken ‘a little of the colour out of my cheeks, this improves it’, and transformed her hair from ‘all fluffy and rather trivial looking before’ to swept back, which ‘has strengthened it, and made it more like my head really’.

There was one loss. The front of Pamela’s dress, an eye-catching blue, had, Sargent said decisively, to go. It was, she explained to her parents, ‘disturbing to the scheme … And much as I regret my pretty blue front I quite see it was rather preclusive of other things in the picture as a whole. For instance both sisters seem to gain by its removal – one’s eye is not checked & held by it … My face also seems to gain significance by its removal.’7 Mary, who had always been suspicious of Pamela’s colour choice, must have been relieved: ‘blue can be so ugly don’t you think?’ she had complained to their mother when Pamela had first announced her sartorial intentions.8

Uncharacteristically, Madeline was causing trouble. At the Ribblesdales’, Sargent had been adamant that ‘Mrs Adeane in particular’ needed to be changed, requiring a further week of sittings. The year before, Charlie Adeane’s patience with ‘that blessed picture’ had worn thin when Madeline had caught influenza while sitting for it. Now, with Madeline still recovering from her infant son’s death, Charlie Adeane, as protective as he was devoted, might prove the spanner in the works. ‘I hope you will use your influence if Charlie is against it,’ Pamela implored her father; ‘it seems a pity if it is so near it shouldn’t be managed.’9 Madeline Wyndham, who could never refuse anything to her ‘Benjamina’, as she called her youngest daughter, replied, ‘I think it would amuse her – & I should trust it was warmer in Sargent’s Studio than it is in [the] large drawing room at 44 this time of year without hot water or hot air which I am sure Sargent’s studio has … you ought write to Madeline & beg her to go up for a week she can be snug as a bug in my bedroom and she & Charlie can be there.’10

In art, as in life, Mary was proving difficult to pin down. Marooned among the rugs, tapestries and antiques that formed the paraphernalia of an artist’s studio,11 as Sargent, muttering unintelligibly under his breath, charged to and from the easel (placed, as always, next to his sitters so that when he stood back he might view portrait and person in the same light),12 Pamela had to exercise all her diplomatic skill when asked what she thought of Sargent’s depiction of Mary. ‘I could say honestly I liked it,’ she told her parents, ‘but I did not think it “contemplative” enough in expression for her.’ And ‘no sooner than I had said the word “contemplative” than he caught at it. “Dreamy – I must make it a little more dreamy!”’ All it needed, apparently, was a touch to Mary’s hooded eyelids, which Pamela agreed were ‘a most characteristic feature of her face’; but ‘of course he will not do it till she sits to him’, she concluded, with not a little exasperation.13

Astonishingly Mary – nicknamed ‘Napoleon’ by her friends for her tendency to make monumental plans that rarely came to pass, and who seemed, in the view of her dear friend Arthur Balfour, ‘to combine into one disastrous whole all that there is of fatiguing in the occupations of mother, a woman of fashion, and a sick nurse’14 – got herself to London, and to Tite Street, in time for the painting to be completed so that it could be displayed at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition that year.

The Wyndham Sisters, to the gratification of all (and doubtless Pamela in particular) was heralded as Sargent’s masterpiece. For The Times, it was simply ‘the greatest picture which has appeared for many years on the walls of the Royal Academy’. Bertie, the elderly Prince of Wales, who had honed his eye for beauty over many years, dubbed the portrait ‘The Three Graces’.

It was, crowed the Saturday Review, ‘one of those truces in the fight where beauty has unquestionably slipped in’.15 Though we now think of Sargent as the Annie Leibovitz of his day – intently flattering at all costs – at that time people did not see it in quite the same way. ‘In all the history of painting’, commented the critic D. S. MacColl in the Saturday Review in 1898, ‘hostile observation has never been pushed so far as by Mr. Sargent. I do not mean stupid deforming spite, humorous caricature, or diabolic possession … rather a cold accusing eye bent on the world.’ MacColl likened Sargent to ‘the prosecuting lawyer or denouncing critics’. His work made the viewer ‘first repelled by its contempt, then fascinated by its life’.16 ‘I chronicle,’ declared Sargent, ‘I do not judge.’17 The dazzling results seduced the aristocracy, but they commissioned him with trepidation. ‘It is positively dangerous to sit to Sargent,’ declared one apprehensive society matron; ‘it’s taking your face in your hands.’18

One oft-repeated criticism, that Sargent did no more than replicate his sitters’ glamour, is perhaps a misunderstanding of the emptiness that his brush was so often revealing. To defeat any accusation that The Wyndham Sisters is simply a pretty picture, one needs only to look at the sisters’ hands. Pamela’s fingers imperiously flick outwards as she lounges back on the sofa, in the most obviously central position as always, unblinkingly staring the viewer down; Mary’s thin hands worry at each other as she perches on the edge of the sofa and gazes ‘dreamily’ off into the distance showing all her ‘delicate intellectual beauty’. Then there is Madeline, who uses her left hand to support herself against the sofa, while her right hand, quelled by sorrow, lies in her lap, patiently facing upwards, cupped to receive the blessings that fate, in recent months, had so conspicuously denied her. Underneath the serenity is the wildness of the Wyndhams, the foreign strain from their mother’s French-Irish blood, that people would remark on time and time again.

Before the sittings began, before the composition had been decided upon, Madeline and Percy Wyndham had arranged a dinner at Belgrave Square for Sargent to meet his sitters properly. Watching the family at home, Sargent had caught on immediately. Rather than paint these women in his studio, as was the norm, he set them in the drawing room of their parents’ house. As one’s eye becomes accustomed to the cool gloom behind the seated figures swathed in layers of white organza, taffeta, tulle, one can make out in the background the portrait of their mother that hung in that room: George Frederic Watts’s portrait of Madeline Wyndham, resplendent in a sunflower-splashed gown, that had caused such a stir at the Grosvenor Gallery a quarter of a century before. Through the darkness, behind Mary, Madeline and Pamela, gleams Madeline Wyndham. So in art, as in life. Sargent had not missed a thing.

ONE

‘Worse Than 100 Boys’

The eldest daughter of the portrait, Mary Constance Wyndham, was born to Percy and Madeline in London, in summer’s dog days, on 3 August 1862. Percy, called ‘the Hon’ble P’ by his friends, was the favoured younger son of the vastly wealthy Lord Leconfield of Petworth House in Sussex. The Conservative Member for West Cumberland, he had a kind heart and the family traits of an uncontrollable temper and an inability to dissemble. It was true of him, as was said of his father, that he had ‘no power of disguising his feelings, if he liked one person more than another it was simply written on his Countenance’.1

Percy’s Irish wife Madeline was different. Known in infancy as ‘the Sunny Baby’,2 she was renowned for her expansive warmth. ‘She is an Angel … She has the master-key of life – love – which unlocks everything for her and makes one feel her immortal,’ said Georgiana Burne-Jones, who, like her husband Edward, was among Madeline’s closest friends.3 Yet in courtship Percy had spoken much of Madeline’s reserve – ‘you sweet mystery’, he called her,4 one of very few to recognize that her personality seemed to be shut up in different boxes, to some of which only she held the key.

Percy and Madeline were both twenty-seven years old. In two years of marriage, they had established a pattern of dividing their time between Petworth, Cockermouth Castle – a family property in Percy’s constituency given to them by his father for their use – and fashionable Belgrave Square, at no. 44. Madeline’s mother, Pamela, Lady Campbell, came over from Ireland for the birth, and during Madeline’s labour sat anxiously with Percy in a little room off her daughter’s bedroom. The labour was relatively short – barely four and a half hours – but it was difficult. Lady Campbell had threatened to call her own daughter ‘Rhinocera’ when she was born because of her incredible size. Mary, at birth, weighed an eye-watering 11 pounds. ‘[T]he size and hardness of the baby’s head (for which I am afraid I am to blame)’, Percy told his sister Fanny with apologetic pride, had required the use of forceps to bring the child into the world. ‘Of course we should have liked a boy but I am very grateful to God that matters have gone so well,’ Percy concluded.5

Percy and Madeline’s daughter held within her person the blood of Ireland and England – a physical embodiment of the vexed union between the kingdoms. Mary grew up on tales of her maternal great-grandfather, Lord Edward FitzGerald, hero and martyr of the 1798 Irish Rebellion. Her own London childhood was punctuated by acts of violence by the newly formed republican Fenian Brotherhood. In 1844 Parliament had debated, at length, the motion ‘Ireland is occupied, not governed’. An ambitious young Benjamin Disraeli drew for the Commons a picture of ‘a starving population, an absentee aristocracy … an alien church, and … the weakest executive in the world’.6 While the novelist Disraeli may have been exercising a little artistic licence – certainly by 1873 only 20 per cent of Ireland’s aristocracy were technically absentee7 – fundamentally his depiction was, and remained, true. Mary and her siblings were brought up to mourn the fate of ‘darling Ireland’.8 With a Catholic strain passed down from Lord Edward’s French wife, they sympathized with the Catholic masses. Mary described herself and her younger brother George in childhood as ‘the Fenians of the family’.9

Lady Edward – ‘La Belle Pamela’ – was officially the adopted daughter of Madame de Genlis, educationalist disciple of Rousseau. In all probability, Pamela was de Genlis’ biological child, by her lover Philippe duc d’Orléans. Orléans was Louis XVI’s cousin. He voted for the King’s execution during the French Revolution, then was guillotined himself when his royal blood rendered him counter-revolutionary. Mary’s was an exotic heritage, romantic, royal, with a hint of disreputableness. Like all her siblings, she was proud of it.

Mary was born at the cusp of a new age, as a myriad of developments – some welcome, others not – forced Britain and her class to reassess their identities. She was born within five years of the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and the famous Huxley–Wilberforce debate on evolution, which her father Percy had attended;10 the 1857 Indian Rebellion which led to control over the sub-continent being passed from the British East India Company to the British Crown; and Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke’s discovery of the Nile’s source. When Mary was born, the working classes (and all women) were still unenfranchised – only one in five men could vote. Neither William Gladstone nor Disraeli, those giants of the late Victorian political arena, had yet formed their own ministries. Upper-class women could not appear in public without a chaperone. During her childhood, Joseph Bazalgette built the Victoria and Albert Embankments to cover the new sewage system that meant the Thames was no longer the city’s chamberpot. The telephone and the first traffic light (short-lived, it was installed outside the Houses of Parliament in 1868, only to explode in 1869, gravely wounding the policeman operating it) were inventions of her early youth. Mary, who as a child had fossils shown and explained to her by her father, was born into a world ebullient in its capacity for exploration and invention but, in post-Darwinian terms, questing and unsure. The British were becoming, as Charles Dilke’s bestselling Greater Britain said, a ‘race girdling the earth’,11 but within their own country the patrician male’s stranglehold on power was being loosened. Mary, hopeful, endlessly curious, surrounded by novelty and change, was a child of that age.

Above all, Mary was the child of a love match – on one side, at least. It had been a coup de foudre for shy, crotchety Percy when as 1860 dawned he met Madeline Campbell in Ireland. Madeline was beautiful, dark and voluptuous, but she was more than that. Her earthy physicality exuded life, and enhanced it in others. ‘People in her presence feel like trees or birds at their best, singing or flourishing according to their own natures with an easy exuberance … she has a peculiar gift for making this world glorious to all who meet her in it,’ said her son George.12

Percy and Madeline were engaged in London in July, and married in Ireland in October. During a brief interim period of separation, as Madeline returned to Ireland, Percy gave voice to his infatuation in sheaves of letters, still breathtaking in their intensity, that daily swooped across the Irish Sea. ‘[D]ear Glory of my Life sweet darling, dear Cobra, dear gull with the changing eyes, most precious, rare rich Madeline sweet Madge of the soft cheeks’,13 said Percy, pouring forth his love, longing and dreams for the future. With barely concealed lust he begged Madeline to describe her bedroom so he could imagine her preparing her ‘dear body’ for bed, and recalled, with attempted lasciviousness charming in its naivety, their brief moments of physical contact – a kiss stolen on a balcony at a ball; a moment knocked against each other in a bumpy carriage ride. ‘[I]f these letters don’t make you know how I love you, let there be no more pens, ink and paper in the world.’14