Полная версия

Map of the Heart

He looked up, and when he saw her, his eyes flared wide, making her glad she’d decided to shower and put on makeup before coming out tonight. “Hi,” he said, extending his hand. “Very happy to meet you.”

Camille could tell he was struggling with his English, so she answered him in French. “Your pictures are truly beautiful,” she said. “Congratulations on this amazing show.”

A smile lit his face. “You’re French, too?”

“My father is. He raised me to speak his native language.”

“He must be from the south,” Gaston said. “Provence? I can hear it in every word you speak.”

The southern part of France had a dialect and cadence all its own, comparable to the unique sound of people from the Chesapeake region, a blend of accents and archaic terms.

“All right, you two. Stop being so foreign and cliquish,” Queenie said.

“We are foreign,” Gaston said with a wink.

“Camille works in photography, too,” Queenie said. “Did she tell you?”

Camille could smell matchmaking a mile off. Her mom and friends and half sisters abhorred a single woman’s status the way nature abhorred a vacuum. Sometimes it seemed her mother had recruited the whole town to find her a boyfriend. For no reason she could fathom, her thoughts strayed to Malcolm Finnemore. The ticked-off client. Not boyfriend material.

“Sorry,” she told Gaston in French. “She always tries to throw me together with random men.”

“Not to worry,” he said, also in French. “I’m an artist. Everybody knows it’s dangerous to hook up with an artist.” He grinned and reverted to English. “So. You like photography.”

“Yes.”

“She specializes in old film and prints,” Queenie said. “I keep trying to get her to do a show here at the Beholder.”

One of Queenie’s assistants came over. “Sorry to interrupt,” she said. “We’ve got a buyer for the big landscape.”

Queenie went straight into action. She pressed her hand against Gaston’s elbow and steered him to the large piece that dominated what had once been the mantel over the hearth.

Camille took the opportunity to pull Billy away from the puppyeyed shopgirl, and they went back out into the street.

“Hey,” said Billy. “She was cute.”

“All twenty-year-olds are cute.”

He sent her a fake-resentful look. “Since when are twenty-year-olds too young for me?”

“We’re thirty-six,” she reminded him.

“In that case, you should take me up on my offer to marry you. I’d make an honest woman of you.”

“Where to next?” she asked, ignoring the suggestion. “Ooh-La-La?”

“Lead on,” he said. “I haven’t seen your mom in a while. Plus, Rhonda always serves those little crab croquettes. They taste like an angel farted in your mouth.”

“No wonder I’d never marry you. You’re too obnoxious.”

“Let’s get over there before the angel farts are gone.”

The shop looked bright and twinkly and inviting, as always. Located in a vine-clad brick building that used to be a milliner’s shop a century before, it had twin display windows facing the street. As always, the display was gorgeous, a blend of beach style and continental chic. Despite the kitschy shop name, Camille’s mother had exquisite taste, and her half sister, Britt, had a keen eye for design.

Cherisse filled the place with supremely interesting things—unique home goods, sommelier tools, glass rolling pins, printed toile curtains, Clairefontaine writing paper and pens that felt just right in the hand. Camille had practically grown up in the boutique, listening to Edith Piaf and Serge Gainsbourg while helping her mom display a set of crystal knife rests or a collector’s edition of Mille Bornes or the Dutch bike game of Stap op.

In the 1990s, the first lady was photographed in the shop, buying a fabulous set of Laguiole cutlery, and business kicked into high gear. Socialites from D.C. and even a couple of celebrities became regular customers. There were write-ups in national magazines, travel articles, and shopping blogs touting the treasures of Ooh-La-La, designating it as a must-visit destination.

Camille owed her very existence to the shop. Although she never realized it growing up, her parents had married for reasons of coldblooded commerce. Her father, Henry, was looking for a marriage path to citizenship. Cherisse, who was fifteen years younger, needed a backer for the shop she’d always dreamed of opening. They both wanted a child, desperately. Desperately enough to believe their shared desire for a home and family was a kind of love. What they eventually had to admit—first to themselves privately, then to each other, and finally to Camille—was that no matter how much they loved their daughter, the marriage wasn’t working for them.

When Camille was eight years old, they sat her down and told her just that.

Their divorce was, as the mediator termed it, freakishly civilized. After a couple of years, Camille adjusted to dividing her time between two households. A few years after the divorce, Cherisse met Bart, and that was when Camille finally learned what true love looked like. It was the light in her mother’s eyes when Bart walked into a room. It was the firm touch of his hand in the small of her back. It was a million little things that simply were not there, had never been there, between her mom and dad.

She was grateful that her parents got along. Bart and her father were cordial whenever they encountered each other. But despite their efforts, the decades-old breakup of her family felt like an old wound that still ached sometimes. When she thought about Julie, she wondered which was harder, to have your family taken apart by divorce, or to lose a parent entirely.

Cherisse, at least, had thrived in her new life. She and Bart had two girls together, Britt and Hilda. Ooh-La-La annexed the building next door, turning it into its sister property, Brew-La-La, the best café in town. All through her high school years, Camille had minded the shop while her two younger half sisters played in the small garden courtyard.

These days, Camille worked behind the scenes with the bookkeeper, Wendell, an insatiable surfer and skateboarder who financed his passion by keeping the books. Despite his shaggy hair and surfer duds, he was smart, intuitive, and meticulous. The sales staff consisted of Rhonda, who was also an amazing cook, and Daphne, a transplant from upstate New York with a mysterious past.

Britt was the resident merchandiser and display designer. Cherisse was in charge of “flying and buying.” Two times a year, she went to Europe to find the lovely offerings that had put the shop on the map. Before losing Jace, Camille used to accompany her on buying trips, soaking in the sights of Paris and Amsterdam, London and Prague. It was a mother-daughter treasure hunt, those unforgettable days.

After Jace died, Cherisse urged Camille to come along on trips the way she used to, but Camille refused. She never flew anywhere. Just the idea of setting foot on a plane sent her into a panic. She never again climbed a mountain or rode a trail, rafted on a river, surfed a wave, or flew on a kiteboard. Other than routine commutes to D.C. for work, she didn’t go anywhere. These days, she regarded the world as a dangerous place, and her job was to stay put and keep Julie safe.

She had failed miserably at that today. She vowed not to make that mistake again.

Rhonda greeted them at the shop entrance with a tray of her legendary crab croquettes.

“I’m never leaving you,” Billy said, helping himself to three of them.

“Promises, promises,” said Rhonda. “Come on in, you two. We’re having a great night. The tourist season is about to kick into high gear.”

Camille’s mother was in her element, greeting visitors, treating even out-of-towners like cherished friends. Billy made a beeline for her. “Hello, gorgeous,” he said, giving her a quick hug.

“Hello yourself,” she said, her face lighting up. Then she noticed Camille. “Glad you came after all. How’s Julie doing?”

“She shooed us both out of the house,” Camille said. “She’s okay, Mom. Thanks for showing up at the hospital. I was a mess.”

“You were not. Or did I miss something?”

You missed me having a meltdown in front of Malcolm Finnemore, Camille thought, but she simply said, “I’m all right now.”

Billy surveyed an antique table displaying a polished punch bowl in the shape of a giant octopus. “The shop looks great, as always.”

“Thanks. Did you see Camille’s new prints? I can’t keep them in stock. I’ve sold four of them already tonight.” She gestured at a display of the three newest prints, matted and framed on a beadboard wall.

The center image was one Camille had rendered from an old daguerreotype of Edgar Allan Poe. Printed on archival paper, the portrait had a haunting quality, as elusive and scary as his poems. Next to those prints were examples of Camille’s own work. She almost never took pictures anymore, so these were from years before. She’d used a vintage large-format Hasselblad, capturing local scenes with almost hyperrealistic precision.

When Jace was still alive, Camille had been a chaperone on one of Julie’s school trips to the White House. It had been one of those days when shot after shot seemed to be sprinkled with fairy dust, from the dragonfly hovering perfectly over a pond in the Kennedy Garden, to a frozen moment of two girls holding hands as they ran along the east colonnade, framed by sheer white columns.

“I love these,” said a browsing tourist. “That’s such a beautiful shot of the White House Rose Garden.”

“Here’s the artist,” Billy said, nudging Camille forward.

“It’s very intriguing,” the woman said. “It looks as if the picture was taken at some earlier time.”

“They’re from six years ago. I was shooting with an antique camera that day,” Camille said.

“My daughter has a great collection of old cameras,” Cherisse said. “She does her own developing and printing.”

“Well, it’s fantastic. I’m going to get this one for a good friend who loves old photographs, too.” She smiled, picking up the Rose Garden print.

Camille was flattered, and she felt a wave of pride. She wished Jace had lived to see this. “Maybe this hobby of yours will turn into something one day,” he used to tell her.

“… on the back,” the woman was saying.

“Sorry,” Camille said. “What was that?”

“I wondered if you could write a message on the back,” she said. “To Tavia.”

“No problem.” The woman seemed a bit quirky, though perfectly nice. Camille found a pen and added a short greeting and her signature to the back of the mat.

“Let’s go drink,” Billy said after she finished. “I can watch you get hit on at the Skipjack.”

“Good plan,” she said, making a face. Guys didn’t hit on her, and he knew it.

She and Billy made their way to the rustic tavern, a nineteenth-century brick building near the fishing pier. The crowd here was friendly and upbeat, spilling out onto the deck overlooking the water.

“Is it just me,” Billy murmured, scanning the crowd, “or do we know at least half the people here?”

“The perks of growing up in a small town,” she said.

“Or the drawbacks. There are at least two women here I’ve slept with. Should I say hi, or pretend I don’t see them?”

“You should order a drink for me, and pick up the tab because I’ve had a rotten day.” Camille stepped up to the bar. “I’ll have a dark-and-stormy,” she said to the bartender.

“Camille, hi,” said a woman, coming up behind her.

Camille tried not to cringe visibly. She knew that voice, with its boarding-school accent and phony friendliness. “Hey, Courtney,” she said.

Drake Larson’s ex-wife wore a formfitting neoprene dress and a stiff smile. Years earlier, she’d been one of the come-heres, the kind that used to make Camille feel self-conscious. Camille was never as cool, as polished, as sophisticated as the kids from the city. One of the reasons she had worked so hard to excel at sports was to find a way to outshine the come-heres.

“I didn’t expect to see you out tonight,” Courtney said. “Vanessa told me your Julie had a terrible accident this morning.”

“She’s fine now,” Camille said, wishing she didn’t feel defensive.

“Well, that’s good to know. I can’t imagine leaving Vanessa after she suffered a head injury.”

“How do you know she hit her head?”

Courtney looked flustered. “That’s just what Vanessa heard. So, Julie’s all right, then, since you’re here drinking with some guy.” She eyed Billy, who was paying for the drinks.

“Julie is fine, and Vanessa is welcome to give her a call,” Camille said.

“I’ll pass that along,” Courtney said. “Vanessa’s busy tonight, though. She and her friends are by the gazebo, listening to the band. Maybe you could text Julie and tell her to join in.”

“Julie decided to stay home,” Camille said.

“You know,” Billy broke in, “just chilling out and being awesome.”

“I see. Well, I suppose she’s reached that awkward stage,” Courtney said, taking a dainty sip of her dirty martini.

Billy regarded her pointedly. “Some people never outgrow it.”

Courtney sniffed, either ignoring or missing the dig. “Kids. They change so quickly at this age, don’t they? Vanessa and Julie used to be such good friends, but lately they don’t seem to have much in common.”

“Is that so?” Billy asked.

“Vanessa is so busy with cheerleader tryouts. Is Julie going out for cheerleading, too?”

Julie would rather have a root canal, thought Camille.

“Julie doesn’t like being on the sidelines,” Billy said.

“She should try cheerleading,” Courtney said. “She has such a pretty face, and the practice is really good exercise. The drills are a great way to get in shape.”

Camille could feel Billy starting to bluster. She gave him a nudge. “Our drinks are ready.”

As they took their cocktails to the deck outside, Camille overheard Courtney boasting to someone else about Vanessa’s latest achievement. She knew she shouldn’t let the woman’s remarks get under her skin, but she couldn’t help it, especially when she looked across the way at the village green and saw a group of kids dancing and having fun. Perky blond Vanessa was the life of the party. Julie didn’t seem to belong anymore. And Camille had no idea how to fix it.

Four

Camille walked home, feeling slightly better after the village social time and two dark-and-stormies. Julie’s light was on upstairs, and Camille could see her through the window, staring at her computer screen, which seemed to be her main channel for socializing these days. Camille hoped the self-isolation was just a phase. She intended to restrict Julie’s screen time, but at the moment she didn’t feel up to a fight.

She let herself in and put down her things. The film was still in the sink along with the shot glasses. She tidied up, trying to shake off the residue of the day. So she’d lost a client. It happened, and now it was done, and the world had not come to an end.

Thanks for nothing. Finnemore was a jerk, she thought, blowing up at her like that. Sure, she’d let him down, but that was no reason for him to rip into her the way he had. Good-looking guys thought they could get away with being mean. She was mad at herself for being attracted to him, and for letting his temper tantrum bug her.

A car’s headlights swept across the front of the house, and crushed shells crackled under its tires. She glanced at the clock—nine P.M.—and went out onto the porch, snapping on the light. Her heart flipped over. Mr. Ponytail Professor was back.

“Did you forget something?” she asked when he got out of the car.

“My manners,” he said.

What the …? “Pardon me?”

“Do you drink wine?” he asked.

“Copiously. Why do you ask?”

He held out a bottle of rosé, the glass beaded with sweat. “A peace offering. It’s chilled.”

She checked the label—a Domaine de Terrebrune from Bandol. “That’s a really nice bottle.”

“I got it from a little wine shop in the village.”

She nodded. “Grand Crew. My father was one of their suppliers. He’s retired now.”

“He was in the wine business, then.”

“He owned an import and distributing firm up in Rehoboth. And why are we having this conversation?”

“I came back to apologize. I got halfway across the bridge and started feeling bad for yelling at you, so I turned around and came back.”

She caught herself staring at him like a smitten coed with a crush on her professor. She flushed, trying to shake off the gape-mouthed attraction. “Oh.” An awkward beat passed. “Would you like to come in?” She held open the door.

“Thought you’d never ask.”

In the kitchen, she grabbed some glasses and a corkscrew. What was he doing back here? “Actually, you did forget something—your sunglasses.” She handed them over.

“Oh, thanks.” He opened the wine and poured, and they brought their glasses to the living room and sat together on the sofa. He tilted his glass toward her. “So … apology accepted?”

She took a sip of the wine, savoring the cool, grapefruity flavor of it. “Apology accepted. But I still feel bad about your film.”

“I know. You made a mistake. I should have been more understanding.” He briefly touched her arm.

Okay, so maybe he wasn’t such a jerk. She stared at her arm where he had touched it. Why was this stranger, whose one-of-a-kind film she’d ruined, taking care of her? Watching him, she tried to figure it out. “I’ve never screwed up a project like that,” she said.

“So what happened?”

“Everything was going fine until I got a phone call from the local hospital that my daughter had been brought in by ambulance. I dropped everything and ran out the door.”

“The girl I met earlier? Oh, man. Is she all right?”

“Yes. Yes, Julie’s fine. She’s upstairs now, online—her favorite place to be.”

“So what was the emergency?”

“She was in a surf rescue class—most kids around here take it in ninth grade. She hit her head and got caught in a riptide.” A fresh wave of panic engulfed Camille as she pictured what could have happened.

“Thank God she’s okay.”

Camille nodded, hugging her knees to her chest. “I was so scared. I held myself together until … well, until you showed up. Lucky you, getting here just in time for my meltdown.”

“You should have said something earlier. If I’d known you rushed off because you got a call about your kid, I wouldn’t have been such a tool.” He offered a half smile that made her heart skip a beat.

At least he acknowledged that he’d been a tool. “Well, thanks for that, Professor Finnemore.”

“Call me Finn.”

She took another sip of wine, eyeing him over the rim of her glass. “You look like a Finn.”

“But not a Malcolm?”

“That’s right. Malcolm is totally different.”

He grinned, flashing charm across the space between them. “How’s that?”

“Well, buttoned down. Academic. Bow tie and brown oxfords.”

He laughed aloud then. “You reduced me to a cliché, then.”

“Guilty as charged.”

“Want to know how I pictured you?” Without waiting for an answer, he rested his elbow on the back of the sofa and turned toward her. “Long dark hair. Big dark eyes. Total knockout in a red striped shirt.” He chuckled at her expression. “I checked out your website.”

Oh. Her site featured a picture of her and Billy on the “about us” link. But a knockout? Had he really said knockout? He was probably disappointed now, because on this particular night, she didn’t look anything like the woman in that photo.

“You look just like your photo,” he said.

Wait. Was he coming on to her? No. No way. She should have looked at his website. Did history professors have websites?

She saw something flicker across his face, an expression she couldn’t read.

“Go ahead,” he said. “You can look me up on your phone. You know you want to.”

She flushed, but did exactly that, tapping his name on the screen. The information that populated the web page surprised her. “According to these search results, you’re a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and a former intelligence officer. You’re now a professor of history at Annapolis, renowned for tracing the provenance of lost soldiers and restoring the memories to their families. You’re an expert at analyzing old photos.”

“Then we have something in common. If you ever come across something mysterious in a picture, I can take a look.”

She couldn’t decide if his self-confidence was sexy or annoying. In the “personal” section of the page, it was noted that he had been married to “award-winning journalist Emily Cutler” for ten years, and was now divorced. She didn’t read that part aloud.

“I’m renowned? You don’t say.” He shifted closer to her and peered at the screen.

“I don’t. Wikipedia says. Is it accurate?”

“More or less.” He grinned. “I don’t know about the ‘renowned’ part. I’ve never done anything of renown. Maybe choosing this exceptional wine. Cheers.” He touched the rim of his glass to hers and took a sip. “So your father was in the business.”

“He’s an expert. Grew up in the south of France.”

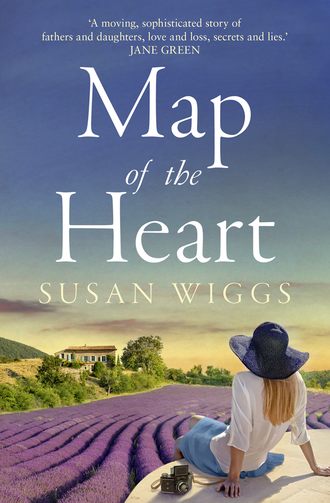

“Then we have something else in common. I’ve been working in France. Teaching at Aix-Marseille University in Aix-en-Provence.”

“Papa was born in that area—a town called Bellerive. It’s in the Var—do you know it?”

“No, but I’ve driven along the river Var, and down to the coast. It’s fantastic, relatively unspoiled by tourists,” he said. “Vineyards, lavender, and sunshine. Do you visit often?”

“I’ve never been.”

“Seriously? You have to go. No one’s life is complete until they’ve gone to the south of France.”

She didn’t want to discuss the matter with him. “Then I’ll have to make sure I live for a very long time.”

“I’ll drink to that.” He surveyed the tall glass case across the room. “You collect cameras?”

“I do. I started taking pictures as soon as I figured out what a camera was, and then I found an old Hasselblad at a flea market that turned out to be a treasure. I taught myself photography with it. That got me interested in the old ones.”

Camille could not remember the first time she’d held a camera in her hands or the first time she’d peered through an eyepiece, but the passion she felt for taking pictures felt new every day. Her passion had died with Jace, and she hadn’t photographed anything since. “I figured out how to restore a camera mostly by trial and error. Lots of error. Lots of late nights bent over a magnifying work lamp, but I love it. Billy’s father worked in the film industry, developing daily rushes, and when we were kids, he showed us the old techniques and equipment to process expired film.”

“So are those pictures your work?” He indicated the two unusual, angular shots of the Bethany Point Light.

“One of them is. I found some old, undeveloped film in a camera, which is pretty much my favorite thing, coaxing images back to life. That shot was taken during a storm in 1924, and I found it so striking that I replicated it myself.” Then she blurted out, “I don’t take pictures anymore. I work in the darkroom on other people’s pictures.”

Her gaze flicked to the vintage Leica in its glass case by the fireplace mantel. It had sat there for five years. No one but Camille remembered the last time she’d used that camera—to take a picture of her husband, moments before he died. She had put the camera away and never touched it again. There was still film in the Leica, a partially exposed roll she had shot that day. Even now, she couldn’t bring herself to develop it.

Several beats of silence passed. She didn’t know why she’d admitted that to this guy. Maybe because she missed it. She used to take pictures, wandering for hours on her travels, a favorite camera thumping against her sternum. She used to disappear into the act of capturing an image, exposing its secrets, freezing a moment. That was all in the past. These days she didn’t go anywhere. She’d photographed Bethany Bay so many times she was numb to its charms and beauty.