Полная версия

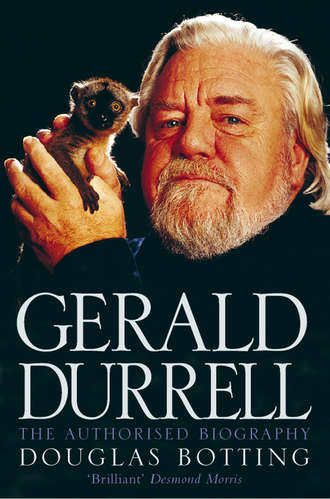

Gerald Durrell: The Authorised Biography

It was in these early outings that Gerald got to know the Corfiot peasants of the locality, many of whom became his friends. There was the cheerful simpleton, an amiable but retarded youth with a face as round as a puffball and a bowler hat without a brim. There was rotund, cheerful old Agathi, past seventy but with hair still glossy and black, spinning wool outside her tumbledown cottage and singing the haunting peasant songs of the island, including her favourite, ‘The Almond Tree’, which began ‘Kay kitaxay tine anthismeni amigdalia …’. Then there was Yani, the toothless old shepherd, with hooked nose and great bandit moustache, who plied the ten-year-old Gerald with olives and figs and the thick red wine of the region (well-watered to a rosy pink).

And then there was the Rose-beetle man, one of the most extraordinary characters of the island, a wandering peddler of the most extreme eccentricity. When Gerald first encountered him in the hills, playing a shepherd’s pipe, the Rose-beetle Man was fantastically garbed, wearing a battered hat that sprouted a forest of fluttering feathers of owl, hoopoe, kingfisher, cockerel and swan, and a coat whose pockets bulged with trinkets, balloons and coloured pictures of the saints. On his back he carried bamboo cages full of pigeons and young chickens, together with several mysterious sacks, and a large bunch of fresh green leeks. ‘With one hand he held his pipe to his mouth, and in the other a number of lengths of cotton, to each of which was tied an almond-size rose-beetle, glittering golden green in the sun, all of them flying round his hat with desperate deep buzzings.’ The beetles, the man mimed – for he was dumb as well as strange – were substitute toy aeroplanes for the village children.

One of the Rose-beetle Man’s sacks was full of tortoises, and one in particular struck the boy’s fancy – a sprightly kind of tortoise, with a brighter eye than most, and possessed (so Gerald was to claim) of a peculiar sense of humour. Gerald named him Achilles. ‘He was undoubtedly the finest tortoise I had ever seen, and worth, in my opinion, at least twice what I had paid for him. I patted his scaly head with my finger and placed him carefully in my pocket.’ But before setting off down the hill he glanced back. ‘The Rose-beetle Man was still in the same place in the road, but he was doing a little jig, prancing and swaying, while in the road at his feet the tortoises ambled to and fro, dimly and heavily.’

From the Rose-beetle Man Gerald obtained several other small creatures that took up residence in the Strawberry-Pink Villa, including a frog, a sparrow with a broken leg, and the man’s entire stock of rose-beetles, which infested the house for days, crawling into the beds and plopping into people’s laps ‘like emeralds’. Perhaps the most idiosyncratic of these creatures was a revolting-looking young pigeon which refused to learn to fly and insisted on sleeping at the foot of Margo’s bed. So repulsive and obese was the bird that Larry suggested calling it Quasimodo. It was Larry who first noticed that Quasimodo was partial to dancing around the gramophone when a waltz was being played, and stomping up and down with puffed-up chest when the record was a march by Sousa. Eventually Quasimodo surprised everybody by laying an egg, whereupon she grew wilder and wilder, abjured the gramophone, and finally, suddenly endowed with the gift of flight, flew out of the door to take up residence in a tree with a large cock bird.

With Gerald rapidly turning into part of the fauna of Corfu, Mother decided it was time he had some sort of education. George Wilkinson was hired for this thankless task. Every morning he would come striding through the olive groves, a lean, lanky, bearded, bespectacled, disjointed figure in shorts and sandals, clutching bundles of books from his own small library, anything from the Pears Cyclopaedia to works by Wilde and Gibbon. ‘Gerry really did everything he could to escape lessons,’ Nancy recalled. ‘He was utterly bored with lessons and with George as a tutor.’ The only way George could gain his attention was to introduce animals into everything he taught, from history (‘Good heavens, look. A jaguar,’ remarked Christopher Columbus as he stepped ashore in America for the first time) to mathematics (‘If it took two caterpillars a week to eat eight leaves, how long would it take four caterpillars?’). It was George who persuaded Gerald to start a nature diary, meticulously noting everything he saw and did every day in a set of fat blue-lined notebooks – a compilation sadly later lost.

Gerald was never at his best within the confines of a room, but outside – whether in a herbaceous border in the garden or a swamp full of snakes – he was a person transformed. Quickly realising this, George instituted a programme of al fresco lessons, out in the olive groves or down by the little beach at the foot of the hill overlooking Pondikonissi (Mouse Island). There, while discussing in a desultory way the historic role played by Nelson’s egg collection at the Battle of Trafalgar, they would float gently out into the shallow bay, and Gerald would pursue his real studies – the flora and fauna of the seabed, the black ribbon-weed, the hermit crabs, the sea-slugs slowly rolling on the sandy bottom, sucking in seawater at one end and passing it out at the other. ‘The sea was like a warm, silky coverlet,’ wrote Gerald later, ‘that moved my body gently to and fro. There were no waves, only this gentle underwater movement, the pulse of the sea, rocking me softly.’

George Wilkinson was an aspiring novelist, but Gerald was so bored by his English lessons that one day he suggested he should write a story of his own, just like his brother Larry (then busy on his second novel, The Black Book). Entitled ‘The Man of Animals’ and written in a wobbly and erratic hand and eccentric, nursery school spelling, the story relates, with uncanny prescience, the adventures of a man who was remarkably like the one Gerald would become:

Right in the Hart of the Africn Jungel a small wite man lives. Now there is one rather xtrordenry fackt about him that is that he is the frind of all animals. Now he lives on Hearbs and Bearis, both of which he nos, and soemtimes, not unles he is prakticly starvyng, he shoot with a bow and arrow a Bird of some sort, for you see he dos not like killing his frinds even wene he is so week that he cann hardly walk!

One of his favreret pets is a Big gray baboon, wich he named ‘Sotine’. Now there are surten words this Big cretcher nows, for intenes if his master was to say ‘Sotine I want a stick to mack a Bow, will you get me one?’ then the Big ting with a nod of his Hede would trot of into the Jungel to get a bamboo fo the Bow and Arrow. But before Brracking it he would bend it so as to now that it would be all right, then breacking it of he would trot back to his master and give it to him and wight for prase, and nedless to say his master would give him a lot …

So far, so good. But now, obviously not averse to experimental writing, the youthful author suddenly switches from the third to the first person, and the adventure continues not from the narrator’s but from the Man of Animals’ point of view.

One day wile I was warking in frount of my porters in Africa a Huge Hariy Hand caught my sholder and I was dragged of into the Jungel by this unseen figer. At last I was put down (not to gently) and I found my self looking into the eyes of a great baboon. ‘Holy mackrarel,’ I egeackted, ‘what the devel made you carry me of like this, ay?’ I saw the Baboon start at my words and then it walked over to the ege of the clearing, beckning me with a Big Hairy Hand …

As well as writing extended narratives in those early Corfu days, Gerald was also trying his hand at verse. At first this shared the simplicity – and the spelling – of his more ambitious works, but combined his passion for natural history with the conventions of pastoral verse:

That coulerd brid of incect land

floating on the waves of light

atractd by the throbing hart

and pulsing viens

this winged buaty

hovers then swops down

siting on the downey pettles

sucking the honey greedly

while the pollen

fall softly

on its red and yelow wings

its hunger qunched

it cralls up the slipry dome

and flys away

to its home

in the skelaton

of a liveing tree!

It was the discovery of a series of mysterious small silken trapdoors set into the floor of a neighbouring olive grove, each about the size of an old shilling piece, that led to an encounter that was to change for ever the direction of Gerald’s life. Puzzled by the trapdoors, he made his way to George Wilkinson’s villa to seek his advice. George was not alone. ‘Seated in a chair was a figure which, at first glance, I thought must be George’s brother,’ Gerald remembered, ‘for he also wore a beard. He was, however, immaculately dressed in a grey flannel suit with waistcoat, a spotless white shirt, a tasteful but sombre tie, and large, solid, highly polished boots.’

‘Gerry, this is Dr Theodore Stephanides,’ said George. ‘He is an expert on practically everything you care to mention. And what you don’t mention, he does. He, like you, is an eccentric nature-lover. Theodore, this is Gerry Durrell.’

Gerald described the tiny trapdoors in the olive grove and Dr Stephanides listened gravely. Perhaps, he suggested, they could go together to look at this phenomenon, since the olive grove lay on a roundabout route back to his home near Corfu town. ‘As we walked along I studied him covertly. He had a straight, well-shaped nose; a humorous mouth lurking in the ash-blond beard; straight, rather bushy eyebrows under which his eyes, keen but with a twinkle in them and laughter-wrinkles at the corners, surveyed the world. He strode along energetically, humming to himself.’

A quick inspection revealed that each trapdoor concealed the entrance to a burrow from which a spider emerged to catch passing prey. The mystery solved, Dr Stephanides shook Gerald’s hand and prepared to go on his way. ‘He turned and stumped off down the hill, swinging his stick, staring about him with observant eyes. I was at once confused and amazed by Theodore. He was the only person I had met until now who seemed to share my enthusiasm for zoology. I was extremely flattered to find that he treated me and talked to me exactly as though I was his own age. Theodore not only talked to me as though I was grown up, but also as though I was as knowledgeable as he.’

Gerald did not expect to meet the man again, but clearly his enthusiasm, high seriousness and powers of observation had made an impression on Theodore, for two days later Leslie came back from town carrying a parcel addressed to Gerald. Inside was a small box and a letter.

My dear Gerry Durrell,

I wondered, after our conversation the other day, if it might not assist your investigations of the local natural history to have some form of magnifying instrument. I am therefore sending you this pocket microscope, in the hope that it will be of some use to you. It is, of course, not of very high magnification, but you will find it sufficient for field work.

With best wishes,

Yours sincerely,

Theo. Stephanides

P.S. If you have nothing better to do on Thursday, perhaps you would care to come to tea, and I could show you some of my microscope slides.

With the doctor and naturalist Theo Stephanides as his mentor, Gerald was to journey through a world of unfamiliar yet strangely intimate forces and phenomena, entering the orbit of Zatopec the poet and the ex-King of Greece’s butler, the microscopic world of the scarlet mite and the one-eyed cyclops bug, the natural profligacy of the tortoise hills, the lake of lilies, the phosphorescent porpoise sea. In the course of his travels he was to become transformed, learning the language and gestures of rural Greece, absorbing its music and folklore, drinking its wine, singing its songs, and shedding his thin veneer of Englishness, so that in mind-set and social behaviour he was never to grow up a true Englishman – a handicap which, like his lack of a formal education, was to prove a tremendous boon in later years.

Theodore Stephanides had just passed forty when Gerald first encountered him. Though the Stephanides family originated from Thessaly in Greece, Theo (like Gerald) was born in India, thus qualifying him for British as well as Greek nationality. At home in Bombay he and his family spoke only English, and it was not until his father retired to Corfu in 1907, when Theo was eleven, that he began to learn Greek properly. After serving in the Greek army in Macedonia in World War One and in Asia Minor in the ensuing war against the Turks, Theo went to Paris to study medicine, later returning to Corfu, where he established the island’s first x-ray unit in 1929, and shortly afterwards married Mary Alexander, a young woman of English and Greek parentage and the granddaughter of a former British Consul on Corfu. Though Theo was a doctor he was never well off, mainly because much of his work he did free of charge, and he and his wife lived in the same rented house in Corfu town throughout the period of their stay on the island.

Theo was a man of immense integrity and courtesy, behaving in the same way to old and young, friends and strangers. He was shy socially, except with close friends, but he had a highly developed sense of humour and loved cracking a good joke, or even a really silly one, at which he would chuckle mightily. He loved Greek dances, and would sometimes perform a kalamatianos by himself. He travelled all over Corfu in his spare time, by car where there were roads and on foot where there were not, singing almost every inch of the way. Whenever Gerald was with him he sang a nonsense song of which he was very fond, in a kind of pantomime English:

There was an old man who lived in Jerusalem

Glory Halleluiah, Hi-ero-jerum.

He wore a top hat and he looked very sprucelum

Glory Halleluiah, Hi-ero-jerum.

Skinermer rinki doodle dum, skinermer rinki doodle dum

Glory Halleluiah, Hi-ero-jerum …

‘It had a rousing tune,’ Gerald recalled, ‘that gave a new life to tired feet, and Theodore’s baritone voice and my shrill treble would ring out gaily through the gloomy trees.’

Theo held views on ecological matters that were very advanced for their time, particularly in Greece, and these planted the germs of a way of thinking in young Gerald’s head that was to stand him in valuable stead in future years. If Theo went for a drive in the country he would throw tree seeds out of the window, in the hope that a few would take root, and he took time off to teach the peasants how to avoid soil erosion when they were tilling the ground, and to persuade them to restrain the goats from devouring everything that grew. As a good doctor he did his best to improve public health on the island, encouraging the villagers to stock their wells with a species of minnow which fed on mosquito larvae and thus helped eradicate malaria.

For Gerald, being tutored by Theo was like going straight to Oxford or Harvard without the usual intermediary steps of primary and secondary schools in between. Theo was a walking, talking fount of knowledge, not only breathtakingly wide-ranging, but deep, detailed and exact. Born before the age of ultra-specialisation, he knew something – sometimes a great deal – about everything. In the course of a day he could engage the young Gerald in an advanced tutorial that would hop effortlessly through the fields of anthropology, ethnology, musicology, cosmology, ecology, biology, parasitology, biochemistry, medicine, history and much else. ‘I had few books to guide and explain,’ Gerald was to write, ‘and Theodore was for me a sort of walking, hirsute encyclopaedia.’

Theo was no mere pedant, with a kleptomaniac gift for collecting sterile, unrelated facts. He was a true polymath, who related the phenomena of past and present existence in a master synthesis, a grand vision which had its feet firmly planted in science but its head peering speculatively among the clouds. ‘Although the classroom basics of biology were a closed book to me,’ Gerald admitted to a friend in his middle age, ‘walks with Theo contained discussions of everything from life on Mars to the humblest beetle, and I knew they were all part and parcel, all interlocked.’

On top of all this, Theo Stephanides bestrode the iron curtain between art and science, for he was not only a doctor and a biologist, but a poet whose friends included some of Greece’s leading poets. ‘If I had the power of magic,’ Gerald once remarked, ‘I would confer two gifts on every child – the enchanted childhood I had on the island of Corfu, and to be guided and befriended by Theodore Stephanides.’ Under Theo’s tutelage Gerald became more than a juvenile version of a naturalist in the classic nineteenth-century mould, more even than a straightforward zoologist of the kind turned out by the British universities of the era – though that was what he was to put as his profession in his passport. For Theo not only taught him what biological life was and how it worked, but imbued him with two principles regarding the role of man in the scheme of things. The first was that life without human intervention maintained its own checks and balances. The second was that the proper role of mankind among living things was omniscience with humility – and the greater of these two was humility.

‘Not many young naturalists have the privilege of having their footsteps guided by a sort of omnipotent, benign and humorous Greek god,’ Gerald would recall. ‘Theodore had all the very best qualities of the early Victorian naturalists, an insatiable interest in the world he inhabited and the ability to illuminate any topic with his observations and thoughts. His wide interests are summed up by the fact that (in this day and age) he was a man who had a microscopic water crustacean named after him, as well as a crater on the moon.’

From 1935 to 1939 Theo and his wife Mary visited the Durrells once a week, arriving after lunch and leaving after dinner. Their young daughter Alexia, often ailing, was usually left at home with her French nanny, because Theo was jealous of his afternoons with Gerald, who was like a son to him. For if Gerald was fortunate to have encountered such a gifted tutor in such a place at such a time in his life, Theodore was no less fortunate to have found an acolyte so innately endowed with responsive gifts of his own. Quite apart from his boundless energy and enthusiasm, his inexhaustible spirit of enquiry – remarkable for one so young, noted Theo – the boy had all the essential qualities of a naturalist. Patience, for a start. He could remain perched in a tree for hours on end, utterly still, utterly enthralled, as he watched the comings and goings of some small creature. Even Nancy, no naturalist, saw this special quality in him: ‘He had an enormous patience when he was very young. He used to make lassoes for catching lizards – lassoes of grass – and he would stay hours crouched in front of a little hole where he knew the lizard was, and then he would pull the noose tight and lasso it.’

Theo also discerned that Gerald lacked the arrogance that most human beings brought to their encounters with animals. Animals, Gerald felt by instinct, were his equals, no matter how small, or ugly, or undistinguished; they were, at a level beyond the merely sentimental, his friends and companions – often his only ones, for he had no great rapport with other children. And the animals, in their turn, sensed this, and responded accordingly, not just when he was a boy on Corfu but throughout all the years of his life.

By corollary, it followed in Gerald’s mind that it was a fundamental moral law that all species had an equal right to exist, this at a time when most human societies observed no ethical principles applicable to living things outside of humankind. It also followed that he had difficulty pursuing the study of natural history in the way that was the common practice of the period: that is by snuffing the life out of living things in order to examine, classify and dissect them in death. ‘Live with living things, I say,’ he was later to declare, ‘don’t just peer at them in a pool of alcohol.’ Gerald, in other words, was a behavioural zoologist (or ethologist) from the very start, and natural history for him was the study of living things – all too evidently living, as his family were to find out soon enough.

The family’s first winter came, coolish and very wet. By now Larry and Nancy, seeking the wilder, lonelier shores of the island, had moved up to Kalami, a remote hamlet on the north-east coast of Corfu, where they took a single-storey, whitewashed fisherman’s house – the White House – on the edge of the sea overlooking a small bay, with the barren hills of Albania only a couple of miles away across the straits. The winter rain in Corfu was almost tropical in density, the sea pounded on the rocks below the house, and the only heating was some smouldering logs in the middle of the room.

When nineteen-year-old Alex Emmett, a family friend who had been at school with Leslie, arrived to join the Durrells for their first Christmas at the Strawberry-Pink Villa, he found Mother still downing gin, Leslie an aimless, rootless, mother-fixated castaway, and Gerry utterly absorbed in his trapdoor spiders and his natural history lessons with Theo Stephan-ides. But for Theo, Emmett reckoned, young Gerry might easily have become a drifter like Leslie.

Having arrived for Christmas, Emmett stayed on for the family’s first full-blown spring on Corfu. It was to prove a season of singular magic. Gerald observed it through eyes round with wonder. The whole island was ‘flower-filled, scented and a-flutter with new leaves’. The cypress trees were now covered with a misty coat of greenish-white cones. Waxy yellow crocuses tumbled down the banks and blue day-irises filled the oak thickets. Gerald recorded: ‘It was no half-hearted spring, this; the whole island vibrated with it as though a great, ringing chord had been struck. Everything and everyone heard it and responded. It was apparent in the gleam of flower-petals, the flash of bird wings and the sparkle in the dark, liquid eyes of the peasant girls.’

The family responded to the spring in their different ways. Leslie blazed away at turtle-doves with his guns. Lawrence bought a guitar and a large barrel of strong red wine and sang Elizabethan love songs which induced a mood of melancholy. Margo perked up, bathed frequently and took an interest in a good-looking but boring young Turk – not a popular choice on a Greek island.

Gerald’s excursions took on an even greater range and interest when, in the summer of 1936, the family moved to another villa on the far side of Corfu town. According to Gerald, it was Larry who provoked the move. He had invited some friends to come to stay on Corfu – Zatopec the poet (an Albanian whose real name was Zarian), three artists called Jonquil, Durant and Michael, and the bald-headed Melanie, Countess of Torro – and he wanted Mother to put them up in the Strawberry-Pink Villa. Since the villa was barely big enough for the family, let alone an untold number of guests, Mother’s circuitous logic decided that the easiest solution was to find a bigger place. In any case, the Strawberry-Pink Villa never had a bathroom worthy of the name, only a separate washroom and a primitive toilet in the grounds, which alone was a compelling enough reason to move on.

The new house, which Gerald was to dub the Daffodil-Yellow Villa, was a huge Venetian mansion called Villa Anemoyanni, after the family who had owned it until recently. It stood on a modest eminence set back from the sea at a place called Sotoriotissa, near Kondokali, overlooking Gouvia Bay to the north of Corfu town. From the attic the children could watch the once-weekly Imperial Airways flying-boat splash down in the bay below. The house had stood empty for three years; it had faded green shutters and yellow walls, and was surrounded by neglected olive groves and untended orchards of lemon and orange trees. Gerald recalled:

The whole place had an atmosphere of ancient melancholy about it, the house with its cracked and peeling walls, the tremendous echoing rooms, its verandas piled high with drifts of last year’s leaves and so overgrown with creepers and vines that the lower rooms were in a perpetual green twilight … The house and land were gently, sadly decaying, lying forgotten on the hillside overlooking the shining sea and dark, eroded hills of Albania.