Полная версия

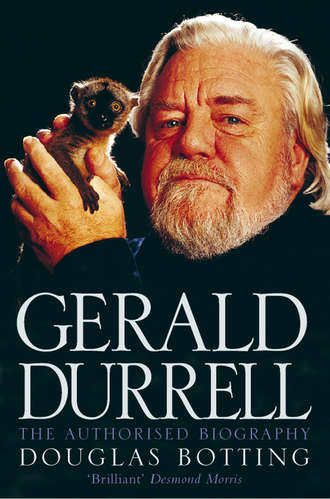

Gerald Durrell: The Authorised Biography

Then come the reptiles. The chameleons have to be sprayed with water and given grasshoppers. The tortoises have to have fruit and greenstuff. And the crocs have to be washed (very difficult, this).

Then it’s lunch-time: soup, chicken with sweet potatoes and green pawpaw, fresh fruit, coffee, cigar. The hardship of collecting! After this, if I have been out all the previous night hunting, I sleep until tea-time; or I plunge into the forest with the hunters. After tea we start all over again: porcupine food, bat food, rat food, monkey milk, mongoose meat, water, etc. etc. I retire about seven, feeling shattered, to my bath, taken in the open before a group of fascinated villagers. Then dinner: duck or deer or porcupine meat, peas, potatoes, sweet, coffee, cigar. Three quick whiskeys, a short stroll round to see everything is alright, and so to bed.

There is so much to tell you about that I could sit down and write ten thousand words if I had time. How a crowd of tiny toddlers appears each day clutching tins, bottles and gourds full of grasshoppers. How a villager tried to strangle his wife down by the river and how the staff and I had to rush down, lay the man out and throw the mother-in-law into the river.

Gerald had now been in Eshobi for many weeks, and the animal collection had grown to such an extent that the Beef House was virtually full. Gerald had learnt the ways of the forest and its wild creatures – and of the Africans among whom he was living. His affection and respect for them – poor people, but brave, big-hearted, loyal and talented in many different ways – had grown, as had theirs for him. Though he was still the ‘Master’, he no longer felt as alien and insecure as he had when he first arrived, and he no longer insisted on the deference he had once thought befitted his status. Indeed, Sanders of the River was even showing signs of going native. ‘Sometimes in the evenings,’ he told Mother, ‘I would go and sit in the kitchen with the staff and discuss such thrilling topics as “Home Rule for the Cameroons” and “Did God Make the World in Seven Days?”’ His departure, when it came, was a matter of some emotion on both sides.

When we were ready to leave Eshobi the village threw a dance in my honour and I was escorted to the main square by the staff and all the village elders and enthroned in state in the front row. Everyone had on their best clothes, ranging from cheap print dresses to shorts made out of old flour bags. Elias, my hunter, was the M.C., clad in a green shirt and pinstripe trousers – God knows where he got them. He had an enormous watch-chain with a huge whistle on it, which he blew loudly to restore order. They do the most curious dances, which are a mixture of nearly every known dance, with the barn dance predominating. Elias, wagging his bottom in the centre, roared the instructions to the dancers: ‘ADvance!! … right turn … meet and waltz … let we set … all move … back we set again … ADvance … right turn … meet and waltz … conduct for yourself … etc. etc.’ When the dance was over the chief made a speech to me. It was really rather funny, because he stood in the centre of the square and so the poor boy who acted as interpreter had to keep running about twenty yards to tell me what he was saying and then run back to hear the next sentence. The speech went something like this:

‘People of Eshobi! You know why we are here tonight … to say goodbye to the Master who has been with us so long. Never in the whole history of Eshobi have we had such a Master … money has flowed as freely from him as water in the river-bed. Those who had the power went to bush and caught beef, for which they were paid handsomely. Those who were weak, the women and children, could obtain money and salt by bringing white ants and grasshoppers. We, the elders of the village, would like the Master to settle here. We would give him land and build him a fine house. We can only hope that he tells all the people in his country how we, the people of Eshobi, tried to help him, and to hope that on his next tour he will come back here and stay even longer.’

This was followed by loud and prolonged cheers, under cover of which the interpreter fainted into the arms of a friend. Then the band, consisting of three flutes and four drums and a triangle, struck up a red-hot version of ‘God Save the King’, and the party broke up.

So, very nearly, did Gerald himself. By now he was in a fairly exhausted condition. He had given his all in an unhealthy and enormously demanding environment. He had been bitten and stabbed by an extraordinary variety of fangs, spines, teeth, beaks, probosces, claws and jaws. He had had jiggers in his toes, ants in his pants, lice in his hair, bugs in his bed, and rats in his tent. He had reckoned on staying up all night packing, so as to be able to leave Eshobi before dawn and get to Mamfe around ten, before the sun got too hot for the animals. But after supper he began to feel very out of sorts, and by nine o’clock he was staggering about as though he was drunk. By ten he could barely walk, and had to be carried out to the latrine by Pious and George, the washboy. He collapsed on his bed, leaving it to the staff to pack up camp. Every five minutes Pious would creep in and peer down at him, making a solicitous ‘tch tch’ noise. Once George came in and tried to cheer him up, telling him that if he died they would never be able to find another Master like him.

‘This was the beginning of the best bout of sandfly fever I’ve had to date,’ Gerald wrote reassuringly to Mother. ‘It’s bloody awful: it doesn’t kill you, or harm you in any way, but while you’ve got it you feel quite sure you’re going to die. You walk as though you are dead drunk, and everything further away than ten feet is blurred and out of focus. You sweat like Hell and your head feels about four times normal size.’

In this condition Gerald now faced the prospect of a five-hour trek through the bush under the blazing equatorial sun. Leaning on the faithful Pious, and tap-tapping along with the aid of a stick, the ailing young white man shuffled along behind a column of sixty black carriers, half of them women. At the first small river he came to he had to be carried across by an elder who had come along to say goodbye. ‘Nearly I cried when I see you carried,’ Pious told him. ‘I make sure you going to die then.’ The track steepened after that, running up a hill at a gradient of one and three, and Gerald had to be half-dragged and carried up by Pious. The main column marched on till it was out of sight. ‘Every two hundred yards we would stop for five minutes,’ Gerald recalled, ‘while I sank down on the path and sweated like a hero in a film and Pious fanned me with a hat.’

One way or another, Gerald got to Mamfe by half-past ten, and by two he was eating lunch with John Yealland at Bakebe. The reunion was heartfelt. Gerald had formed a high opinion of John’s qualities as an ornithologist and a man, relishing his slow drawl and dry humour, his wisdom and kindness. It was a pleasure to be with a fellow-countryman again, to speak plain English, swap the news of the last few months, and inspect each other’s impressive collections of birds and animals.

After three days’ rest at Bakebe, Gerald began to feel much better, only suffering from the disappointment of not having got an angwantibo. This disappointment was to be short-lived. One day, not long after his return to Bakebe, Gerald set off for a reconnaissance of the nearby mountain N’da Ali, which had almost sheer sides thickly covered with forest. Gerald’s aim was to find a camp site and to spend ten days or so trying to catch some of the large numbers of chimpanzees reputed to live there. He wrote home:

I set off early one morning on a borrowed bike, a small boy on the crossbar with a bag of beer and other nourishment, to meet the hunter who was going to lead me up. We had gone about four miles, and I was just wondering if my legs were going to hold out, when in the distance I saw a man marching along with a bag made out of palm leaves in his hand. Thinking it was yet another Pouched Rat or Brush-tailed Porcupine, I dismounted and waited for him. When he got near I saw to my surprise that he was one of my ex-hunters from Eshobi. When he got to within hailing distance I asked him what he had got, and he replied that it was small beef. I regret to say that on peering into the basket the only sound I could produce was a sort of strangled ‘Arrrrr …’ Then I loaded the hunter with my gear, threw the boy off the crossbar, and hanging the Angwantibo round my neck fled frantically back home again.

Gerald had obtained his first angwantibo in the nick of time, for shortly afterwards there came word from England – a tip-off from his Whipsnade friend Ken Smith – that the legendary collector Cecil Webb of the London Zoo had set sail for the Cameroons with the express intention of catching angwantibo. A veteran of expeditions all over the world, Webb regarded Durrell and Yealland as novices and upstarts. For their part, they saw him as an irritating rival who was over the hill.

Eventually, Webb caught up with them. ‘He is a huge, lanky man (six foot six, I believe),’ Gerald reported to Mother, ‘with a protruding jaw and faded blue eyes. We found him clad in faded blue jeans and an enormous sort of straw sun-bonnet which made me want to giggle. He asked, with a careless air that almost strangled him, if we had still got the Angwantibo, to which we replied that it was thriving. I am going up to Bemenda in a few days time and will pass through Mamfe, where he is now. I shall then take great pleasure in telling him that we have now got three (3) Angwantibo!!!!!!!!’

Webb did not go away empty-handed, however, for Gerald was duty bound to hand over to him for delivery to London Zoo the most remarkable animal in his collection – Cholmondeley (pronounced Chumley) the chimpanzee. Gerald had acquired Cholmondeley from a District Officer who had asked him if he could find a home for a chimp at London Zoo. Gerald had agreed, imagining that the creature would be about a year old and around eighteen inches high. He was amazed when a lorry arrived with a large crate in the back containing a full-grown chimpanzee of eight or nine years of age, with huge arms, a bald head, a massive, hairy chest that measured at least twice the size of Gerald’s, and bad tooth growth that made him look like an unsuccessful prize-fighter.

I opened the crate with some trepidation. Cholmondeley gave a little hoot of pleasure, gathered up the long chain which was attached to a collar round his neck, hung the loops daintily over his arm, and stepped down. Here he paused briefly to shake my hand in the most regal and dignified manner before walking into the house as if he owned it. He gazed around the living room of our humble grass hut with the air of a middle-European monarch inspecting a hotel bedroom suspected of containing bed bugs. Then, apparently satisfied, he ambled over to the table, drew out a chair and sat down, crossing his legs and staring at me expectantly.

We stared at each other for a bit, and then I got out my cigarettes. Immediately Cholmondeley became animated. It was quite obvious that after his long journey he wanted a cigarette. I handed him the packet, and he removed a cigarette, carefully put it in his mouth, and then replaced the packet on the table. I handed him a box of matches, thinking this might possibly fool him, but he slid the box open, took out a match, lit the cigarette, and threw the matches back on the table. He crossed his legs again and lay back in his chair inhaling thankfully and blowing great clouds of smoke out of his nose.

Cholmondeley had other predilections. Hot, sweet tea was one. He would drink it out of a battered mug the size of a tankard, balancing it on his nose to drain the last dregs of syrupy sugar at the bottom. Then he would either hold out the mug for more or hurl it as far away as he could. He had also developed a fondness for beer, though Gerald only proffered it to him once, when he drank a whole bottle very quickly, with much lip-smacking and delight, till he was covered in froth and began to turn somersaults. After that he was given nothing stronger than lemonade or tea. Gerald parted with this extraordinary character with much regret, though he was destined to meet up with him again soon enough.

At last, in July, the time came to wind down operations and pack up the expedition. The rains were beginning, and Gerald had run out of money. He had spent heavily on stores, staff and accommodation, but especially on the birds, animals and reptiles which made up his huge collection. The situation was dire enough for him to swallow his pride and telegraph home for a loan, receiving by return the sum of £250 (more than £5000 in today’s money) from Leslie’s girlfriend Doris, the off-licence manageress.

The remaining camp stores were sold off, as John Yealland recorded in his diary:

Gerald started to sell up the home this evening and did a brisk trade with his topee and umbrella and my oilskin, along with two sacks of maize, half a sack of coconuts, crockery, pots and pans and some spare cartridges. Such was Gerald’s salesmanship that he even sold an alarm clock which never lost less than one and a half hours in twenty-four for 15 shillings. He also sold a watch which he dropped on a concrete floor at Victoria and which still ticks though it doesn’t move its hands. So now we dine off cracked plates, but at least we have some money for cables to Belle Vue and Chester Zoos.

Gerald and John had originally planned to sail on 24 June, but their collection had grown so huge that the crates and boxes – five hundred cubic feet in volume – would not fit into the hold of the ship they had booked, and it sailed without them. Eventually they were able to secure berths and cargo space on a banana boat, the SS Tetela, sailing from the port of Tiko a whole month later, on 25 July, and began to prepare for their departure.

‘You cannot just climb aboard a ship with your animals,’ Gerald pointed out, ‘and expect the cook to feed them.’ A vast hoard of foodstuffs had to be got together, gathered from all over the country, and soon the expedition hut at Kumba resembled a market, with bananas, pawpaws, pineapples, oranges, eggs, sacks of corn, potatoes and beans, and the carcass of a whole bullock strewn across the floor.

It was at this point that Gerald went down with malaria, and lay feverish and ill with a temperature of 103 for a week. The plan was to drive down to Tiko during the night of 24 July, arriving at dawn on the day the ship was due to sail. But when the doctor called on the day before their departure, he was aghast at the idea of Gerald going anywhere. ‘You should be kept in bed for at least a fortnight,’ he thundered. ‘You can’t travel on that ship.’ Otherwise, he bluntly informed the ailing Englishman, he would die.

But Gerald went, alternately sweating and shivering in the cab of the lorry as it ploughed down the mud road through the first rains of the season. A torrential downpour half-drowned the animals as they were being loaded on board at the docks, and though he felt like death Gerald insisted on drying the sodden creatures and giving them their night feed. Then the steward poured him a whisky which, he recalled, ‘could have knocked out a horse’, and he lay down in his cabin convinced he was going to die.

But he didn’t. He was lucky with the weather on the voyage home, and soon began to revive with the fresh sea air. The crew found a playpen for Sue the chimpanzee, and titbits and blankets for any monkey with a sniff or a cough. The only casualty was a mongoose that staged a breakout and jumped overboard.

At 4 p.m. on Tuesday, 10 August 1948, the Tetela tied up at Garston Docks, Liverpool, and Gerald Durrell and John Yealland stepped back on to dry land at the end of their African adventure. They had been away more than seven months, and had brought back nearly two hundred creatures all told – among them ninety-five mammals (including the three angwantibo, forty monkeys, a baby chimp and a giant white mongoose), twelve reptiles and ninety-three rare birds. This cargo was sufficiently exotic to attract the attention of the national press. ‘Awantibos, ahoy!’ cried the headlines. ‘The Awantibo is here today … only once seen alive in a European zoo!’

‘Eventually,’ Gerald was to recall, ‘the last cage was towed away, and the vans bumped their way across the docks through the fine, drifting rain, carrying the animals away to a new life, and carrying us towards the preparations for a new trip.’

The expedition had been an enormous challenge, and had turned out a considerable triumph, putting Gerald Durrell and John Yealland in the front rank of British zoo collectors and field workers, and marking the definitive starting point of Gerald’s spectacular career.

* In pidgin all animals are called ‘beef’. There are four kinds: ‘small’, ‘big’, ‘bad’ and ‘bery bad’ beef.

* Spelt ‘Andraia’ in Gerald’s later book. The correct spelling is ‘Andreas’, and the man is still alive.

NINE In the Land of the Fon Second Cameroons Expedition 1948–1949

With the African animals finally settled in their English zoos, and a bit of profit jingling in his pocket, Gerald was free to go home to Bournemouth. He was greeted as if he had come home from the moon, and his residual malaria, diagnosed by Alan Ogden, the family doctor, as the particularly severe strain Plasmodium falciparum, was viewed like a badge of courage brought back from some distant battlefield. Leslie was living with Doris nearby, and Margaret and her children were still in residence at Mother’s house. At Christmas Larry and Eve returned from Argentina and temporarily rejoined the fold.

Gerald was already a very good story-teller, and he held the house in St Alban’s Avenue in thrall with tales of his extraordinary adventures. In the comforting ambience of kith and kin he began to ease up after the strenuous travails of the last year. Slowly – perhaps not so slowly – his mind turned to the long-lost local girlfriends of that far-off pre-Cameroons era of the year before, whose company he had been deprived of for so long during the chaste jungle months. He even thought of taking a holiday – a proposal that provoked an odd reaction. ‘Nothing annoys a collector more,’ he was to recall, ‘than to return after six months of bites, scratches, trouble and toil and to announce to one’s friends that one is thinking of taking a short holiday, only to be told – “But you’ve just had one!”’

It was during Gerald’s brief hometown visit that he encountered a young woman whose equivocal charms were to alternately intrigue and appall him for a long time to come. Her real name was Diane, but he was later to bequeath her the unforgettable nom d’amour of Ursula Pendragon White. His subsequent account of this flawed paragon is intricate and involved, but there is no doubting his fascination with her divine looks and her less than divine language, and the spell cast over him by both. ‘I found,’ he was to recall, ‘that she was the only one who could arouse feelings in me that ranged from alarm and despondency to breathless admiration and sheer horror.’

Ursula was an ex-public school young woman from Canford Cliffs, at the posh end of Bournemouth (though later, to disguise her identity, Gerald was to say she was from Lymington in the New Forest). Gerald first set eyes on her on the top of a double-decker bus in Bournemouth town centre, his attention initially drawn by her ‘dulcet Roedean accents, as penetrating and all-pervading as the song of a roller canary’.

Gerald’s sister Margaret remembered Ursula as ‘a young dolly bird with long blonde hair who sat around in a droopish fashion which was very irritating to the rest of us’. According to Gerald’s later description, though (again, perhaps to disguise her identity), Ursula had dark, curly hair. Her eyes were huge, fringed with long dark lashes and set under very dark eyebrows. ‘Her mouth,’ he recalled, ‘was of the texture and quality that should never, under any circumstances, be used for eating kippers or frogs’ legs or black pudding.’

When Ursula stood up to get off the bus, Gerald saw that she was tall, with long, beautifully shaped legs and ‘one of those willowy, coltish figures that turn young men’s thoughts to lechery’. He reckoned, sighing, that it was unlikely he would ever set eyes on her again. But within three days she was back in his life, and remained so off and on for the next five years.

Encountering her again at a friend’s birthday party, where she greeted him effusively as ‘the bug boy’, Gerald, by his own account, ‘gazed at her and was lost’. It was not just her looks that infatuated him, it was also the sounds she made – ‘her grim, determined, unremitting battle with the English language’. For this svelte and spirited beauty suffered from a sort of oral dyslexia, and was for ever forcing words and phrases to do her bidding, expressing meanings they were never meant to express. There was no guessing what fantastical imagery she would conjure up next. She would speak excitedly of ‘Mozart’s archipelagoes’, of having bulls ‘castigated’, and of ‘ablutions’ to prevent ‘illiterate babies’. In Ursula’s world there was never fire without smoke, and rolling moss gathered no stones. In the prim confines of Bournemouth society ‘she dropped bricks at the rate of an unskilled navvy helping at a building site’.

There began a lengthy (and possibly unconsummated – the evidence is unclear) game of romantic cat and mouse. To give Ursula the impression that he was her equal in wealth, class and breeding, Gerald persuaded Margaret’s ex-husband Jack Breeze to drive him to his rendezvous with her in the vintage Rolls-Royce Jack owned at the time, with Jack smartly turned out in his BOAC officer’s uniform, for all the world like some pasha’s personal chauffeur. Ferried around in style, Gerald took Ursula to dinner at the Grill Room (‘She has the appetite of a rapacious python,’ he was warned, ‘and no sense of money’); to a symphony concert at the Pavilion (where her Pekinese puppy jumped out of its basket and created havoc in the auditorium); and into the country for gin and shove ha’penny at the ancient Square and Compass pub, where the aged yokels were mesmerised by her unique brand of English (‘A fine young woman, sir,’ commented one pickled veteran, ‘even though she’s a foreigner’). Gerry never got on terribly well with his girlfriends’ fathers in those days, and Ursula’s, stuffy and well-heeled, was conventional enough to brandish a horse-whip one night when he brought her home late, threatening to thrash him within an inch of his life if it ever happened again.

But while Ursula was Gerald’s distraction, it was the animal wilds of Africa that were his obsession, and she was convinced that sooner rather than later her beloved would end up tied in knots by a gorilla, or devoured by a lion before breakfast. One day she telephoned him. Her voice was so penetrating that he had to hold the receiver away from his ear.

‘Darling,’ she cried, ‘I’m engaged!’

‘I confess that my heart felt a sudden pang,’ Gerald was to write of this poignant moment, ‘and a loneliness spread over me. It was not that I was in love with Ursula; it was not that I wanted to marry her – God forbid! – but suddenly I realised that I was being deprived of somebody who could always lighten my gloom.’

Ursula duly married her intended. A long time later, she and Gerald met one last time, at a smart but stuffy old Edwardian café called the Cadena, among the elderly seaside gentry. As she came through the door it was obvious she was far gone with her second child.

‘Darling!’ she screamed. ‘Darling! Darling!’

‘She flung her arms round me,’ Gerald remembered, ‘and gave me a prolonged kiss of the variety that is generally cut out of French films by the English censor. She made humming noises as she kissed, like a hive of sex-mad bees. She thrust her body against mine to extract the full flavour of the embrace and to show that she cared, really and truly. Several elderly ladies, and what appeared to be a brigadier who had been preserved (like a plum in port) stared at us with fascinated repulsion.’

‘I thought you were married,’ said Gerald, tearing himself from her with an effort.