Полная версия

Listen to This

A lot of younger listeners seem to think the way the iPod thinks. They are no longer so invested in a single genre, one that promises to mold their being or save the world. This gives the lifestyle disaster called “classical music” an interesting new opportunity. The playlists of smart rock fans often include a few twentieth-century classical pieces. Mavens of electronic dance music mention among their heroes Karlheinz Stockhausen, Terry Riley, and Steve Reich. Likewise, younger composers are writing music heavily influenced by minimalism and its electronic spawn, even as they hold on to the European tradition. And new generations of musicians are dropping the mask of Olympian detachment (silent, stone-faced musician walks onstage and begins to play). They’ve started mothballing the tuxedo, explaining the music from the stage, using lighting and backdrops to produce a mildly theatrical happening. They are finding allies in the “popular” world, some of whom care less about sales and fees than the average star violinist. The borders between “popular” and “classical” are becoming creatively blurred, and only the Johann Forkels in each camp see a problem.

The strange thing about classical music in America today is that large numbers of people seem aware of it, curious about it, even knowledgeable about it, but they do not go to concerts. The people who try to market orchestras have a name for these annoying phantoms: they are “culturally aware non-attenders,” to quote an article in the magazine Symphony. I know the type; most of my friends are case studies. They know the principal names and periods of musical history: they have read what Nietzsche wrote about Wagner, they can pick Stravinsky out of a lineup, they own Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations and some Mahler and maybe a CD of Arvo Pärt. They follow all the other arts—they go to gallery shows, read new novels, see art films. Yet they have never paid money for a classical concert. They almost make a point of their ignorance. “I don’t know a thing about Beethoven,” they announce, which is not what they would say if the subject were Henry James or Stanley Kubrick. This is one area where even sophisticates wrap themselves in the all-American anti- intellectual flag. It’s not all their fault: centuries of classical intolerance have gone into the creation of the culturally aware non-attender. When I tell people what I do for a living, I see the same look again and again—a flinching sideways glance, as if they were about to be reprimanded for not knowing about C-sharps. After this comes the serene declaration of ignorance. The old culture war is fought and lost before I say a word.

I’m imagining myself on the other side—as a forty-something pop fan who wants to try something different. On a lark, I buy a record of Otto Klemperer conducting the Eroica, picking this one because Klemperer is the father of Colonel Klink, on Hogan’s Heroes. I hear two impressive loud chords, then what the liner notes allege is a “truly heroic” theme. It sounds kind of feeble, lopsided, waltzlike. My mind drifts. A few days later, I try again. This time, I hear some attractive adolescent grandiosity, barbaric yawps here and there. The rest is mechanical, remote. But each time I go back I map out a little more of the imaginary world. I invent stories for each thing as it happens. Big chords, hero standing backstage, a troubling thought, hero orating over loudspeakers, some ideas for songs that don’t catch on, a man or woman pleading, hero shouts back, tension, anger, conspiracies—assassination attempt? The nervous splendor of it all gets under my skin. I go to a bookstore and look at the classical shelf, which seems to have more books for Idiots and Dummies than any other section. I read Bernstein’s essay in The Infinite Variety of Music, coordinate some of the examples with the music, enjoy stories of the composer screaming about Napoleon, and go back and listen again. Sometime after the tenth listen, the music becomes my own; I know what’s around almost every corner and I exult in knowing. It’s as if I could predict the news.

I am now enough of a fan that I buy a twenty-five-dollar ticket to hear a famous orchestra play the Eroica live. It is not a very heroic experience. I feel dispirited from the moment I walk in the hall. My black jeans draw disapproving glances from men who seem to be modeling the Johnny Carson collection. I look around warily at the twenty shades of beige in which the hall is decorated. The music starts, with the imperious chords that say, “Listen to this.” Yet I somehow find it hard to think of Beethoven’s detestation of all tyranny over the human mind when the man next to me is a dead ringer for my dentist. The assassination sequence in the first movement is less exciting when the musicians have no emotion on their faces. I cough; a thin man, reading a dog-eared score, glares at me. When the movement is about a minute from ending, an ancient woman creeps slowly up the aisle, a look of enormous dissatisfaction on her face, followed at a few paces by a blank-faced husband. Finally, three smashing chords to finish, obviously intended to set off a roar of applause. I start to clap, but the man with the score glares again. One does not applaud in the midst of greatly great great music, even if the composer wants one to! Coughing, squirming, whispering, the crowd suppresses its urge to express pleasure. It’s like mass anal retention. The slow tread of the Funeral March, or Marcia funebre, as everyone insists on calling it, begins. I start to feel that my newfound respect for the music is dragging along behind the hearse.

But I stay with it. For the duration of the Marcia, I try to disregard the audience and concentrate on the music. It strikes me that what I’m hearing is an entirely natural phenomenon, the sum of the vibrations of various creaky old instruments reverberating around a boxlike hall. Each scrape of a bow translates into a strand of sound; what I see is what I hear. So when the cellos and basses make the floor tremble with their big low note in the middle of the march (what Bernstein calls the “wham!”) the impact of the moment is purely physical. Amplifiers are for sissies, I’m starting to think. The orchestra isn’t playing with the same cowed force as Klemperer’s heroes, but the tone is warmer and deeper and rounder than on the CD. I make my peace with the stiffness of the scene by thinking of it as a cool frame for a hot event. Perhaps this is how it has to be: Beethoven needs a passive audience as a foil. To my left, a sleeping dentist; to my right, a put-upon aesthete; and, in front of me, the funeral march that rises to a fugal fury, and breaks down into softly sobbing memories of themes, and then gives way to an entirely new mood—hard-driving, laughing, lurching, a bit drunk.

Two centuries ago, Beethoven bent over the manuscript of the Eroica and struck out Napoleon’s name. It is often said that he made himself the protagonist of the work instead. Indeed, he fashioned an archetype—the rebel artist hero—that modern artists are still recycling. I wonder, though, if Beethoven’s gesture meant what people think it did. Perhaps he was freeing his music from a too specific interpretation, from his own preoccupations. He was setting his symphony adrift, as a message in a bottle. He could hardly have imagined it traveling two hundred years, through the dark heart of the twentieth century and into the pulverizing electronic age. But he knew it would go far, and he did not weigh it down. There was now a torn, blank space on the title page. The symphony became a fragmentary, unfinished thing, and unfinished it remains. It becomes whole again only in the mind and soul of someone listening for the first time, and listening again. The hero is you.

2 CHACONA, LAMENTO, WALKING BLUES BASS LINES OF MUSIC HISTORY

At the outset of the seventeenth century, as the Spanish Empire reached its zenith, there was a fad for the chacona, a sexily swirling dance that hypnotized all who heard it. No one knows for certain where it came from, but scattered evidence suggests that it originated somewhere in Spain’s New World colonies. In 1598, Mateo Rosas de Oquendo, a soldier and court official who had spent a decade in Peru, included the chacona in a list of locally popular dances and airs whose names had been “given by the devil.” Because no flesh-and-blood person could resist such sounds, Oquendo wrote, the law should ignore whatever mischief they might cause.

The devil did fine work: the chacona is perfectly engineered to bewitch the senses. It is in triple time, with a stress on the second beat encouraging a sway of the hips. Players in the chacona band lay down an ostinato—a motif, bass line, or chord progression that repeats in an insistent fashion. (“Ostinato” is Italian for “obstinate.”) Other instruments add variations, the wilder the better. And singers step forward to tell bawdy tales of la vida bona, the good life. The result is a little sonic tornado that spins in circles while hurtling forward. When an early-music group reconstructs the form—the Catalan viol player Jordi Savall often improvises on the chacona with his ensemble Hespèrion XXI—centuries melt away and modern feet tap to an ancient tune.

The late Renaissance brought forth many ostinato dances of this type—the passamezzo, the bergamasca, the zarabanda, la folia—but the chacona took on a certain notoriety. Writers of the Spanish Golden Age savored its exotic, dubious reputation: Lope de Vega personified the dance as an old lady “riding in to Seville from the Indies.” Cervantes’s novella La ilustre fregona (The Illustrious Scullery-Maid), published in 1613, has a scene in which a young nobleman poses as a water carrier and plays a chacona in a common tavern, to the stamping delight of the maids and mule boys. He sings:

So come in, all you nymph girls,

All you nymph boys, if you please,

The dance of the chacona

Is wider than the seas.

Chacona lyrics often emphasize the dance’s topsy-turvy nature—its knack for disrupting solemn occasions and breaking down inhibitions. Thieves use it to fool their prey. Kings get down with their subjects. When a sexton at a funeral accidentally says “Vida bona” instead of “Requiem,” all begin to bounce to the familiar beat—including, it is said, the corpse. “Un sarao de la chacona,” or “A Chaconne Soirée,” a song published by the Spanish musician Juan Arañés, presents this busy tableau:

When Almadán was married,

A wild party was arranged,

The daughters of Anao dancing

With the grandsons of Milan.

A father-in-law of Don Beltrán

And a sister-in-law of Orfeo

Started dancing the Guineo,

With the fat one at the end.

And Fame spreads it all around:

To the good life, la vida bona,

Let’s all go now to Chacona.

A surreal parade of wedding guests ensues: a blind man poking girls with a stick, an African heathen singing with a Gypsy, a doctor wearing pans around his neck. Drunks, thieves, cuckolds, brawlers, and men and women of ill repute complete the scene.

King Philip II, the austere master of the Spanish imperium, died in 1598, around the time that the chacona first surfaced in Peru. In the final months of his reign, Philip took note of certain immoral dances that were circulating in Madrid; religious authorities had warned him that the frivolity rampant in the city resembled the decadence of the Roman Empire. The debate continued after Philip’s death. In 1615, the King’s Council banned from public theaters the chacona, the zarabanda, and other dances that were deemed “lascivious, dishonest, or offensive to pious ears.” In truth, officialdom had little to fear from these naughty little numbers. They give off a frisson of rebellion, yet the established order remains intact. The errant nobles in Cervantes’s story resume their proper roles; the characters in “Un sarao de la chacona” surely return to their usual places the following day. Tellingly, Arañés dedicated his collection of songs to his employer, the Spanish ambassador to the Holy See. Courtly life had no trouble assimilating the chacona, which soon became a respectable form in what we now call classical music.

The subsequent history of the chacona cuts a cross-section through four centuries of Western culture. As the original fad subsided, composers avidly explored the hidden possibilities of the dance, ringing intricate variations on a simple idea. It passed into Italian, French, German, and English hands, assuming masks of arcane virtuosity, aristocratic elegance, minor-key cogitation, and high-toned yearning. Louis XIV, whose empire eclipsed Philip’s, danced la chaconne at the court of Versailles; in the modern era, the French term for the dance has generally prevailed. Johann Sebastian Bach, in the final movement of his Second Partita for solo violin, wrote a chaconne of almost shocking severity, rendering the form all but unrecognizable. In the Romantic age, the chaconne fell from fashion, but amid the terrors of the twentieth century composers once again picked it up, associating it with the high seriousness of Bach rather than the ebullience of the original. The chaconne has continued to evolve in music of recent decades. In 1978, György Ligeti, an avant-gardist with a long historical memory, wrote a harpsichord piece titled Hungarian Rock (Chaconne), which revived the Spanish bounce and infused it with boogie-woogie.

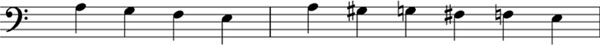

The circuitous career of the chaconne intersects many times with that of another ostinato figure, the basso lamento. This is a repeating bass line that descends the interval of a fourth, sometimes following the steps of the minor mode (think of the piano riff in Ray Charles’s “Hit the Road Jack”) and sometimes inching down the chromatic scale (think of the “Crucifixus” of Bach’s B-Minor Mass, or, if you prefer, Bob Dylan’s “Simple Twist of Fate”):

If the chaconne is a mercurial thing, radically changing its meaning as it moves through space and time, these motifs of weeping and longing bring out profound continuities in musical history. They almost seem to possess intrinsic significance, as if they were fragments of a strand of musical DNA.

Theorists warn us that music is a non-referential art, that its affective properties depend on extra-musical associations. Indeed, with a change of variables, a rowdy chaconne can turn into a deathly lament. Nothing in the medium is fixed. “I consider music by its very nature powerless to express anything,” Stravinsky once said, warding off sentimental interpretations. Then again, when Stravinsky composed the opening lament of his ballet Orpheus, he reached for the same four-note descending figure that has represented sorrow for at least a thousand years.

FOLK LAMENT

Across the millennia, scholars have attempted to construct a grammar of musical meaning. The ancient Greeks believed that their system of scales could be linked to gradations of emotion. Indian ragas include categories of hasya (joy), karuna (sadness), raudra (anger), and shanta (peace). In Western European music, songs in a major key are thought to be happy, songs in a minor key sad. Although these distinctions turn hazy under close inspection—Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, in muscular C minor, defies categorization—we are, for the most part, surprisingly adept at picking up the intended message of an unfamiliar musical piece. Psychologists have found that Western listeners can properly sort Indian ragas by type, even if they know nothing of the music. Likewise, the Mafa people of Cameroon, who inhabit remote parts of the Mandara Mountains, easily performed a similar exercise with Western samples.

The music of dejection is especially hard to miss. When a person cries, he or she generally makes a noise that slides downward and then leaps to an even higher pitch to begin the slide again. Not surprisingly, something similar happens in musical laments around the world. Those stepwise falling figures suggest not only the sounds that we emit when we are in distress but also the sympathetic drooping of our faces and shoulders. In a broader sense, they imply a spiritual descent, even a voyage to the underworld. In a pioneering essay on the chromatic lament, the composer Robert Müller-Hartmann wrote, “A vision of the grave or of Hades is brought about by its decisive downward trend.” At the same time, laments help to guide us out of the labyrinth of despair. Like Aristotelean tragedy, they allow for a purgation of pity and fear: through the repetitive ritual of mourning, we tame the edges of emotion, give shape to inner chaos.

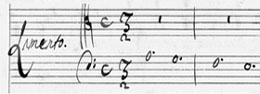

In 1917, the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, a passionate collector of folk music, took his Edison cylinder to the Transylvanian village of Mânerău and recorded the bocet, or lament, of a woman pining for her absent husband: “Change me to a rainbow, Lord, / To see where my husband is.” The melody goes down four sobbing steps:

This pattern shows up all over Eastern European folk music. In a village in the Somogy region of Hungary, a woman was recorded singing a strikingly similar tune as she exclaimed, “Woe is me, what have I done against the great Lord that he has taken my beloved spouse away?” At Russian weddings, where a symbolic “killing the bride” is part of the nuptial rite, the wailing of the bride often presses down a fourth. Comparable laments have been documented in the Mangystau region of Kazakhstan and in the Karelian territories of Finland and Russia, with more distant parallels appearing among the Shipibo-Conibo people, in the upper Amazon, and the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea.

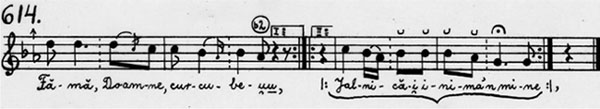

If you twang those four descending notes forcefully on a guitar, you have the makings of flamenco. The motif is especially prominent in the flamenco genre known as siguiriya, which stems from older genres of Gypsy lament. On a 1922 recording, Manuel Torre sings a classic siguiriya, with the guitarist El Hijo de Salvador repeatedly plucking out the fateful figure:

Siempre por los rincones I always find you

te encuentro llorando … weeping in the corners …

Flamenco is more than lament, of course; it is also music of high passion. As Federico García Lorca wrote of the siguiriya, “It comes from the first sob and the first kiss.”

Of course, not every descending melody has lamentation on its mind. Lajos Vargyas’s treatise Folk Music of the Hungarians contains a song called “Hej, Dunaról fuj a szél,” whose slow-moving, downward-tending phrases display the markers of musical sadness. But it is actually a song of flirtation, with the singer turning a bleak situation to her advantage: “Hey, the wind’s blowing from the Danube / Lie beside me, it won’t reach you.” Likewise, certain laments lack telltale “weeping” features: the aria “Che farò senza Euridice?” from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice, begins with a decorous, upward-arching phrase in a sunny major mode.

In other words, there are no globally consistent signifiers of emotion. Music is something other than a universal language. Nonetheless, the lament topos occurs often enough in various traditions that it has become a durable point of reference. Peter Kivy, in his book Sound Sentiment, argues that musical expression falls into two categories: “contours,” melodic shapes that imitate some basic aspect of human speech or behavior; and “conventions,” gestures that listeners within a particular culture learn to associate with particular psychological states. The falling figure of lament is more contour than convention, and it is a promising thread to follow through the musical maze.

THE ART OF MELANCHOLY

Emotional archetypes came late to notated or composed music. In the late Middle Ages, a stylized array of chantlike lines worked equally for texts of lust, grief, and devotion. Hildegard of Bingen, abbess of Rupertsberg (1098–1179), exhibited one of the first strongly defined personalities in music history, yet the fervid mysticism of her output emanates more from the words than from the music. The opening vocal line of Hilde-gard’s “Laus Trinitati” (“Praise be to the Trinity, who is sound, and life”) has much the same rising and falling shape as “O cruor sanguinis” (O bloodshed that rang out on high”). Still, you can identify a few explicitly emotional effects in medieval music—“not mere signs but actual symptoms of feeling,” in the words of the scholar John Stevens. The lament contour might be among the oldest of these. In the twelfth-century liturgical drama The Play of Daniel, the prophet lets out a stepwise descending cry as he faces death in the lion’s den: “Heu, heu!”

As the Middle Ages gave way to the Renaissance, “symptoms of feeling” erupted all over the musical landscape. Guillaume de Machaut (d. 1377), the most celebrated practitioner of the rhythmically pointed style of Ars Nova, dilated on the pleasures and pains of love, and you can hear a marked difference between the gently rippling figures of “Tant doucement” (“So sweetly I feel myself imprisoned”) and the stark descending line of “Mors sui” (“I die, if I do not see you”). This emphasis on palpable emotion, bordering on the erotic, was probably connected to the growing assertiveness of the independent nobility and of the merchant classes. In the following century, Marsilio Ficino, the Florentine Neoplatonist philosopher, described music as presenting “the intentions and passions of the soul as well as words … so forcibly that it immediately provokes both the singer and the audience to imitate and act out the same things.” The conception of music as a spur to individual action was an implicit challenge to medieval doctrine, and, indeed, Ficino’s revival of Greek ideas led to suspicions of heresy.

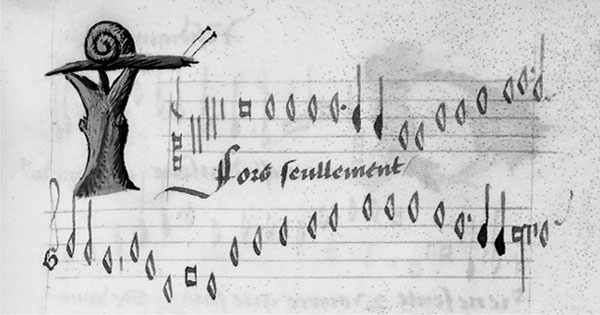

When secular strains infiltrated sacred music, a major new phase in composition began. The high musical art of the later Renaissance was polyphony, the knotty interweaving of multiple melodic strands. A cadre of composers from the Low Countries—cultivated first by the dukes of Burgundy and later by such patrons as Louis XI of France and Lorenzo the Magnificent of Florence—wrote multi-movement masses of unprecedented complexity, perhaps the first purposefully awe-inducing works in the classical tradition. These composers adopted a new practice, English in origin, of letting a preexisting theme take control of a large-scale piece. At first, the melodies were taken from liturgical chant, but popular tunes later came into play. The master of the game was Johannes Ockeghem (d. 1497), who is said to have sung with a deep bass voice and who lived to a grand old age. Around 1460, Ockeghem wrote a chanson titled “Fors seulement,” whose lovelorn text begins with the lines “Save only for the expectation of death / No hope dwells in my weary heart.” Its opening notes match up with the lament contour of various folk traditions:

Ockeghem’s song became widely popular, inspiring dozens of arrangements; a version by Antoine Brumel added a text beginning with the words “Plunged into the lake of despair.” In due course, the tune served as a cantus firmus, or “fixed song,” for settings of the Mass. The Kyrie of Ockeghem’s own Missa Fors seulement begins with a terraced series of descents, the basses delving into almost Wagnerian regions. The illusion of three-dimensional space resulting from that vertical plunge is one novel sensation that Ockeghem’s music affords; another is the cascading, overlapping motion of the voices, an early demonstration of the magic of organized sound. As the Mass goes on, the song of despair is transformed into a sign of Christ’s glory.