Полная версия

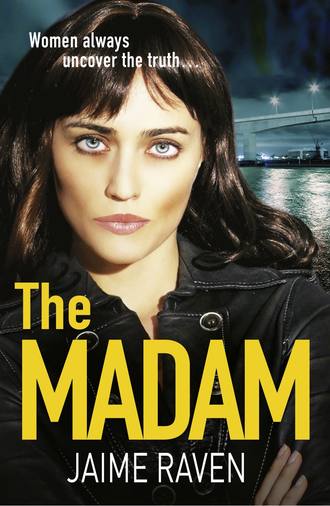

The Madam

‘Jesus.’

‘There was no evidence to suggest that anyone else had been in the room. The security cameras hadn’t picked anything up, and the only prints on the knife belonged to me. I couldn’t convince them that someone had come into the room while we were having sex.’

‘What about the champagne?’ she said. ‘Did they check to see if it was drugged?’

‘There was no champagne. Whoever killed Benedict took the bottle and glasses away. The hotel’s room service claimed they hadn’t delivered anything to the room.’

‘But what about the post-mortem? They do toxicology tests, don’t they? That should have shown up any knock-out drugs in your system.’

‘Well, it didn’t. My lawyer said not all drugs can be detected during an autopsy.’

I got up and walked around, touching things, while letting the memories crowd my mind. Benedict’s blood had been spattered across the sheets, the walls, the carpet. It was smeared across my own breasts and face and even now it was the dominant theme of recurring nightmares.

‘The police were certain that I murdered Benedict, but my lawyer put up a convincing argument that I was defending myself,’ I said. ‘There was the head wound and some other bruises. There’d obviously been a struggle, so the CPS agreed to drop the murder charge to manslaughter to make sure they got a conviction, provided I pleaded guilty.’

‘You were lucky you didn’t get life, Lizzie.’

That was true. But I was unlucky to spend time behind bars for something I didn’t do.

‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Let’s get out of here. I need some fresh air.’

A few minutes later we walked out into the car park. As we approached the Fiesta I noticed something white under one of the windscreen wipers. I thought it was a leaflet or a flyer. But when I pulled it out I saw it was a piece of lined paper from a notebook. There were two short sentences scrawled on it in black felt tip ink.

Let it rest, Lizzie. Open up old wounds and you’ll regret it.

2

Southampton central police station. An eight-storey building near the city’s enormous port complex.

Scar waited in the car while I went into reception and asked for DCI Martin Ash. I gave my name and explained that I didn’t have an appointment. The duty officer ran his eyes over me like I was something nasty that had been blown in from the street. He probably knew instinctively that I was just out of prison. Maybe it’s something that cops can tell simply by looking at you.

Eventually he picked up the phone and called the Major Investigations Department. After a brief conversation he cradled the receiver. ‘The DCI’s out. But DS McGrath got back a few minutes ago and is coming down to see you.’

And with that he returned to whatever he was doing before I arrived. I sat on a bench and thought about the note. Back in town for less than an hour and already I’d been warned off. But that was cool because it meant that someone was worried. They knew – or suspected – that I was going to stir things up and they weren’t happy about it.

DS McGrath stepped out of a side door into the reception area after about five minutes. He was mid-to-late thirties and looked vaguely familiar. In fact I was surprised that I couldn’t immediately place him because he had the kind of looks that a girl doesn’t easily forget. Dark wavy hair, sharp distinctive features. Handsome in a rugged, natural way. A Holloway pin-up for sure.

‘Hello, Miss Wells. I’m Detective Sergeant Paul McGrath.’

He thrust out his hand for me to shake, but I ignored it as a matter of principle. Despite his good looks and obvious sex appeal he was still part of the establishment that had put me away.

‘I just talked to DCI Ash on the phone,’ he said, withdrawing his hand a little self-consciously. ‘He’s on his way back to the office and he’s happy to see you. He wants me to take you upstairs and give you a cup of coffee.’

‘I’d prefer tea,’ I said.

He flashed a thin smile, showing a gap in his front teeth. ‘That’s no problem. Just come and make yourself comfortable while you wait.’

The corridors were familiar. I was led through them after I was arrested. Very little had changed. The posters that adorned the walls issued the same old warnings about drugs, knives and casual sex.

We walked through an empty open-plan office to a small room at one end. There was a desk and several chairs. View of a bus stop.

‘Take a seat and I’ll fetch you that tea,’ McGrath said.

I sat and stared at the wall behind the desk. More posters were pinned to it, along with memos and newspaper cuttings. On the desk was a photo of Martin Ash with his family – a plump wife and two young sons. There was another framed photo on the grey filing cabinet to the right of the desk. It showed two men together – Ash and Neil Ferris. They were wearing suits and smiling for the camera. I thought back to the hours they spent interviewing me in a tiny windowless room. Playing good cop, bad cop. Trying desperately to get a confession. Pumping me with tepid tea and false reassurances.

God knows how many times they made me recount what had happened in that hotel room. They wanted to know exactly what Benedict and I had got up to before he was killed. Did we have intercourse? Did he pay me in cash before we got started?

They asked me time and again why my fingerprints were on the knife if I’d never seen it before. And why the hotel staff knew nothing about the bottle of champagne I said had been delivered to the room.

It was a tough time for me. I was confused and disoriented. And angry because they refused to accept that I’d been the victim of a well-planned stitch-up.

McGrath returned with tea in a plastic cup. I couldn’t help but notice how tight his trousers were. They showed off a narrow waist and well-toned ass. It was the kind of thing that used to turn me on, and if I was honest with myself it still did. It was a stark reminder of how hard it was going to be to decide which path to follow in respect of my sexuality.

‘Careful,’ he said, as he handed the cup to me. ‘It’s hot.’

I thanked him and drank some. He was right. It was scalding, but it tasted pretty good.

McGrath sat on the edge of the desk and folded his arms. I could smell his sweat and aftershave. After four years without a man it was difficult to ignore.

‘Do you know how long Ash will be?’ I asked.

‘Any minute now,’ he said. ‘He’s probably pulling into the car park as we speak.’

I sipped some more tea and met his gaze. His eyes were pale blue and alert. He seemed to be searching my expression for something.

After a beat, he said, ‘You probably don’t remember me. But I was one of the officers who brought you in. I was a DC then.’

‘That so?’

‘You were in a bit of a state. I don’t think I’ve ever seen so much blood.’

I was suddenly conscious of my appearance. I knew I looked pale and drawn. My clothes were ill-fitting and my hair was a mess. I couldn’t help wondering if he’d already given me marks out of ten.

‘I can barely believe it was so long ago,’ he said. ‘It’s flown by.’

A bolt of anger shot through me. ‘I’m glad you think so. But then you weren’t locked up in some poxy cell for most of the time.’

He looked mortified.

‘Shit, I’m sorry I said that, Miss Wells. It came out wrong. It was insensitive.’

‘Too fucking right it was,’ I said.

‘I wasn’t thinking. Please accept my apology.’

‘That’s the trouble with you coppers,’ I said. ‘You’re brainless fucking twats who don’t think.’

He was about to respond when DCI Ash walked into the room wearing a broad grin that revealed sharp little teeth.

‘What is it with you, McGrath?’ he said. ‘I leave you alone with a lady for ten minutes and you’ve already managed to upset her.’

McGrath looked from me to Ash and then back to me. His face reddened and for some reason I felt sorry for him.

‘I’ve got a big mouth, guv,’ he said.

‘So tell me something I don’t already know.’

Ash came further into the room and looked down at me. He was wearing a blue suit and white shirt with a starched collar. The creases in the trousers were razor sharp. His thinning hair was slicked back with gel. He’d put on weight since I last saw him and had a more generous paunch.

‘Good to see you again, Lizzie.’

I arched my brow at him. ‘Really?’

‘For sure. It’s not often that someone I put away looks me up the day they get out. It is kind of freaky, though. Should I be concerned?’

‘Only if you’re a lying bastard with something to hide,’ I said.

The smile became a hearty chuckle which stayed with him as he walked behind the desk and folded his bulk into the chair.

‘Very funny, Lizzie,’ he said. ‘I can see you’re still a spirited little madam even after a few years in the slammer.’

I never did like Ash. There had always been an arrogance in his tone that angered me. From the moment he took me into custody he treated me like slime. His favourite put-down line back then was: ‘So how should I describe you, Lizzie? Or should I say Madam Lizzie? What are you: a brass, a tom, a whore or a prossy?’

‘Try escort,’ I’d responded that first time, but he thought it was funny and told me not to be ridiculous.

‘Escort implies that you’re sort of respectable,’ he’d said. ‘When in fact you’re anything but.’

I could tell he hadn’t changed. Still arrogant, obnoxious and judgemental. And that made him dangerous.

‘I’ve actually been expecting you to show up,’ he said. ‘Soon as I got wind that your girlfriend was in town and asking lots of questions.’

I stared at him. ‘How the hell did you know that?’

‘Come off it, Lizzie. We’re not stupid. Some strange bird looking like Al Capone suddenly appears on the scene and starts pumping people about things that are none of her business. Didn’t it occur to you that we’d get suspicious, especially when she began touting for information on a killing that happened years ago?’

‘How did you make the connection?’

‘It wasn’t difficult,’ he said. ‘She has a few contacts down in Portsmouth. One of them happens to be a snout for me. He alerted me that she was snooping around and we did some checking.’

‘So why didn’t you talk to her?’

‘No reason to. She hadn’t done anything wrong. And besides, we guessed that she was sniffing around for you. I’m assuming you’re here to tell me why.’

‘In a second.’ I took the folded note from my jeans and leaned over the desk to hand it to him. ‘First look at that.’

‘What is it?’

‘Someone put it on my girlfriend’s windscreen after we left the car for a short time.’

He held the note between his fingers as though the paper might be radioactive.

Then slowly he unfolded it and read aloud, ‘“Let it rest, Lizzie. Open up old wounds and you’ll regret it.”’

He grunted and dropped the note onto the desk.

‘So what do you make of it?’ I asked him.

He looked at me quizzically. ‘What am I meant to make of it?’

‘Well, if I’m not mistaken that’s a threat. And aren’t the police supposed to protect people who are threatened?’

‘This is a joke, right?’

Did I expect any other reaction? Probably not. Scar had told me the cops wouldn’t take it seriously. But, at least the note had given me an excuse to drop in on Ash, and that was good enough for now.

‘I want to know who wrote it,’ I said. ‘And I’d like to know if I should be scared.’

He threw a glance at McGrath. ‘So what’s your take on it, detective? Do you think we’re in the business of protecting confessed killers?’

To his credit, McGrath chose to ignore the question. He said, ‘Where was the car parked, Miss Wells?’

‘At The Court Hotel,’ I said. ‘We were inside for about half an hour. My girlfriend picked me up from Holloway and we drove there.’

‘Are you sick in the fucking head or something?’ Ash snarled. ‘What were you doing going back to that place?’

‘I wanted to see the room again,’ I said. ‘I wanted to refresh my memory.’

‘Why, for fuck’s sake?’

‘Because now that I’m out I intend to find out who stitched me up.’

The room got quiet. Both coppers stared at me as though I’d suddenly broken out in huge red welts.

Ash eventually broke the silence. ‘So prison turned you into a raving lunatic then.’

‘I didn’t kill Rufus Benedict,’ I said. ‘Someone went to a lot of trouble to make sure I got the blame for it.’

‘That’s bollocks,’ Ash said, his voice filled with agitation. ‘There’s no question that you stabbed that poor, pervy bugger to death. You even pleaded guilty to manslaughter, for Christ’s sake. But, hey, you served your time so move on. Go back on the game or wash dishes in a curry house. I don’t care. Just don’t piss around trying to be a detective.’

‘I’m serious about this,’ I said.

‘You’re insane more like.’

‘That note suggests otherwise,’ I pointed out. ‘Someone is worried enough to try to warn me off.’

‘How do we know you didn’t write it yourself?’

‘Check the CCTV cameras in the hotel car park for starters,’ I said.

‘That’ll prove nothing. You might have got someone to plant it.’

‘Why would I do that?’

‘Because you’re a nut. Because you want attention. Because you’ve decided it’d be fun to waste our time. There are a hundred and one reasons.’

‘Get real,’ I said. ‘I’m telling you it was put there.’

He took a deep breath and exhaled it through his nose.

‘Well, there’s nothing I can do about it. No crime has been committed, and I don’t intend to divert resources to helping a lowlife killer like you.’

I let that one pass and said, ‘So how about answering some questions about Benedict’s murder. There were things that didn’t come out at the trial.’

He’d already started to get up from the chair. Now he stopped and looked down at me, his big hands resting on the desk.

‘You’ve got a fucking nerve, Lizzie. I’ll say that for you. But no way am I going to encourage you to make a nuisance of yourself. You’re clearly mad to even think you can pull this crap. So listen carefully. I don’t want you or Scarface to go around upsetting people. It’ll just cause a heap trouble for everyone, including me.’

‘You can’t stop me asking questions,’ I said.

He stood up and drew in a lungful of air. At the same time his stomach flopped ungraciously over his belt.

‘Don’t cross me, Lizzie. Just count yourself lucky that you’re not going to spend the rest of your life in prison. You’re out now because we let you get away with a manslaughter plea. So I suggest you make the most of your freedom. In fact I share the sentiments of whoever wrote that frigging note. So don’t go stirring things up because it won’t take much to put you back inside.’

I held his gaze. ‘Does that mean you won’t investigate the threat that’s been made against me?’

He glared at me, the veins in his neck swelling.

‘Just get the fuck out of here before I really lose my temper.’

McGrath was instructed to escort me down the stairs and out of the building. He didn’t say a word until we got to the exit, and I sensed he was a little embarrassed by his boss’s outburst.

Out in the sunshine, he said, ‘I’m sorry about that. The governor isn’t known for his good nature and even temper.’

I shrugged. ‘I shouldn’t have expected anything else from him.’

‘Well, we’re not all like Ash. As far as I’m concerned you committed a crime and you served out your punishment. Therefore, you’re once again a regular member of the community with the same rights as everybody else.’

He handed one of his cards to me. ‘I don’t for a minute condone what you’re doing, Miss Wells, but if you receive any more threats then give me a call. My mobile number is on the back.’

I mumbled my thanks, slipped the card into my back pocket.

‘It might be useful if you gave me your number,’ he said.

I turned on the phone that Scar had given me and read out the number.

‘Ash was right, though,’ he said. ‘You shouldn’t go raking over old coals. The last thing you want is to get into trouble again and wind up right back in the clink.’

‘Thanks for the advice,’ I said.

‘I’m serious, Miss Wells. If you’re not careful you could get into serious trouble again.’

I pressed out a grin. ‘Don’t see why. As you just said I served my sentence so like everyone else I’m now free to make an arse of myself as long as I keep it legal.’

I walked back to the car. Scar was puffing on a menthol and blowing the smoke out the window. She waited until I was strapped into the passenger seat.

‘Didn’t go well, did it?’ she said.

‘Is it that obvious?’

‘You look fit to explode.’

‘Ash is a bastard.’

‘So I gather.’

I told her what had transpired in his office.

‘I did warn you that it wouldn’t be easy,’ she said. ‘I just can’t see anyone helping you out, especially the Old Bill. I mean, why would they?’

It was the same question I’d been asking myself for ages, and I still didn’t have an answer.

‘Let’s go to the flat,’ I said.

Scar gunned the engine. ‘Bevois Valley here we come.’

I lowered the side window and breathed in the familiar tang of salty sea air. It beat the smell of prison piss and disinfectant.

‘By the way, the Valley is close to the town’s red light district,’ I said. ‘Is this your way of trying to make me feel at home?’

Scar gave me a look. ‘It was the cheapest pad I could find. And it’s within walking distance of the bar we’re going to tonight.’

‘That so? What kind of bar is it?’

‘It’s big, dark and noisy. You’ll love it.’

‘Really? Let me guess – it’s called the Mercury Club?’

‘Hey, that’s right. You know it?’

‘Everyone knows it. It used to be the town’s biggest gay venue.’

‘Still is,’ she said cheerfully. ‘And you know what? I can’t wait to show you off there.’

We drove along the dock road. A cruise ship was berthed in the port terminal, waiting to transport hundreds of well-heeled passengers to exotic locations. Maybe one day I’d be among them. It was something I used to dream about when, as a child, I’d watch the QE2 heading out into the Solent, its bow cutting through the water like a knife through jelly.

The city was much as I remembered it, except there were more flats, more speed cameras, more students and more cars. It was the Southampton I’d grown up in. A vibrant community with a colourful ethnic mix; where ugly new buildings nestled beside stone walls and ramparts from bygone eras; where women were gobby and people spoke with an accent that fell somewhere between cockney and west country.

My father had worked in the docks before he succumbed to bowel cancer at the age of thirty-five, leaving my mother to take care of my brother and me. Life was never the same after that. My father and I had been very close. He was the one who read me bedtime stories and paid me the most attention. I was a daddy’s girl for sure and his death left me bereft.

My mother took it really hard and she never really came to terms with her loss. His death carved a hole in her life that couldn’t be filled. She was forever searching for a meaning to her existence, and unfortunately for me she eventually found it in religion.

And there, just up ahead, was St Mary’s church where she did all her praying. It’s the largest church in the city, and my mother was fond of telling me that the sound of its bells had inspired the words of the song The Bells of St Mary’s, which was sung by Bing Crosby in the film of the same name. I was never sure why she thought I was interested.

She used to drag me to the services, but I hated it. I hated the smell of the polished wood, and I hated the hypocrisy that permeated the air like toxic fumes. When I was fifteen I called a halt to it, stood my ground. My mother had given up on me by then anyway and didn’t go to war over the issue.

‘Your mother and brother live near here, don’t they?’ Scar said. ‘You want to go see them?’

The prospect of seeing my mother did not fill me with joyous anticipation.

‘Tomorrow,’ I said. ‘There’s no hurry.’

We drove on into Bevois Valley, a run-down inner city area full of student flats, live music venues and grubby takeaways. It’s a few minutes walk from the decrepit flat I used to live in with Todd, the loser who fathered Leo. He stuck around long enough to realise a child meant cost and commitment. Then he disappeared, leaving me to cope by myself. He never saw his son, and the last I heard he’d moved up north. Even the cops couldn’t trace him to tell him little Leo had died.

The flat that Scar had rented was just off the main drag opposite a small motorcycle repair shop. It was on the first floor of a scruffy terraced house. Peeling paint on the window frames. Chunks of brickwork missing. An overflowing wheelie bin out front.

It might have been a grim place in a grim part of town, but to someone who had spent nearly four years in a poky cell it wasn’t half bad. Even when I saw the flat’s interior I didn’t flinch, though I was sure most people would have.

The carpet was grey and threadbare throughout. Wallpaper clung precariously to the walls. Some of it had peeled away to reveal rough, brown surfaces beneath. The ceilings were smoke-ravaged and lumpy and the net curtains were the colour of wet sugar.

There was a living room, bedroom, bathroom and small kitchen that barely held two people.

But amazingly it felt like home. Maybe that was because the finer things in life had always eluded me. Money had always been scarce. I got used to second-hand furniture, Primark clothes, same-day loans and fake jewellery. Real cash only came my way when I started turning tricks, and all that money went into paying off debts and building society accounts for Leo’s future.

‘I’ve stocked up the fridge,’ Scar said. ‘So we’ve got plenty of food and drink. I’ve kept a tally of everything I’ve spent.’

Scar was excited. Could barely keep still.

‘Why don’t you unpack your bag?’ she said. ‘I’ll pour us a couple of drinks.’

The bedroom looked crowded with a double bed. Scar had bought a duvet and cover-set in black. She’d placed candles on the tiny bedside tables and there was a bunch of fresh flowers in a vase on the dressing table.

I threw my holdall onto the bed and unzipped it. Took out everything I owned and it didn’t amount to much. A few T-shirts, another pair of jeans, sweater, papers, some jewellery, a small photo album filled with pictures of Leo, my brother’s letters. I planned to go shopping soon to buy whatever I needed. There was at least five thousand pounds in the accounts, assuming Scar had spent a couple of grand on the flat and various other expenses. We’d cope on that for a few months, then decide what to do and where to go.

Back in the living room, Scar poured us beers and lit a couple of spliffs. The beer went down a treat and the spliff helped ease away the tension in my bones.

It all seemed so unreal. Like it was happening to someone else and not me. I was out. No more lockdowns. No more crappy food. No more shit from the screws. No more mind-numbing boredom.

I had my life back, but even so I didn’t feel there was any real cause for celebration. I just felt like I had things to do, an objective to achieve. Until that was sorted I felt I had to hold back.

‘Chill out, babe,’ Scar said. ‘It’s time to scream from the rooftops, for pity’s sake. You’re back in the land of the living.’

She was right and it made me feel stupid. There was no harm in enjoying the moment. The other stuff could wait. I owed it to myself to relax a little and savour the glorious buzz of freedom.

And then I felt Scar’s fingers in my hair. She came up behind me as I was staring out through the window at the bright blue sky above Southampton. Her touch was soft and gentle, and it set my body on fire.