Полная версия

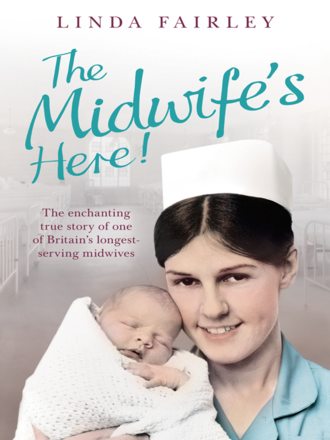

The Midwife’s Here!: The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

‘It’s these ruddy suspender belts,’ Lesley winced. ‘Iron beds, prickly blankets and metal clasps on suspender belts are a lethal combination. Making beds in stockings should carry a “high voltage” warning! Come on, let’s go and sort out the linen cupboard. I think we’ve earned it.’

She gave me a little wink and I followed her through the ward and into the large linen store near the main doors. This was a godsend, I’d learned. Each ward had one, and it was a little haven where you could make yourself look busy and hide from Sister whenever you needed a breather.

‘Have you heard the gossip?’ Lesley asked when we were safely inside. She handed me a stack of pillowcases to fold, though they were already in a fairly neat pile. I was all ears.

‘Cassie Webster and Sharon Carter have been suspended for a month for stealing bread from the dining room.’

‘Never!’ I exclaimed, genuinely shocked. The hospital food was truly terrible. We lived on a diet of rubbery eggs and greasy strips of bacon for breakfast and the ubiquitous lumpy mash and unidentifiable meat for lunch and dinner. Afternoon tea was the only enjoyable offering of the day, when we had tea and fairy cakes and freshly baked Hovis loaves, which we slathered with jam and butter. Everyone tried to get to the first sitting for afternoon tea, else there wouldn’t be much left, but I’d never heard of anyone stealing the bread before.

‘Seems they fancied taking a couple of Hovis loaves back to their flat with them, and Matron, of all people, caught them red-handed! Walked right into them, apparently, as they smuggled them out the door, still warm and wrapped in their aprons!’

I gulped as Lesley continued the tale, knowing how seriously this offence would be viewed. ‘Matron was purple with rage as she marched them to her office, shouting as she did so. Nancy Porter heard every word and it’s gone all over the hospital!’

Lesley jutted out her chin, pursed her lips and pushed out her chest, Miss Morgan-style. ‘You have stained your reputations as upstanding, trustworthy young ladies!’ she mimicked. ‘Your mothers will be distraught when they find out about this disgraceful carry-on. Do not darken the door of the MRI for one month. You are suspended with immediate effect. Take the time to contemplate the error of your ways.’

‘Shhhhh!’ hissed a young nurse I’d never seen before, who suddenly loomed in the linen cupboard doorway. ‘I can hear you on the ward – and Matron’s coming!’

Lesley and I both fell into a heap, stuffing flannels between our teeth to stifle our laughter. We hid behind the door until the sound of Matron’s clicking heels subsided. We’d had a lucky escape and we wanted to keep it that way, so we held our breath as we strained to hear her distant tones telling some poor soul to report to her office at once. ‘It appears you need a reminder …’ we heard Matron saying before her voice faded away. No doubt she was going to deliver a lecture about skirt lengths or tidy hair, her two bugbears.

Before I finished my shift that day I went to see Mrs Pearlman.

‘Hello, my dear, I’m glad you’ve come,’ she said. ‘I have something for you.’ She reached for an elegant gold watch that was lying on top of her locker and held it out to me.

‘Oh, I couldn’t possibly …’ I began. I had never seen the watch before and I knew patients were not meant to have valuables lying about the place. I was pretty sure nurses were not meant to accept gifts like this from patients, either. I’d seen Sister Gorton confiscating bottles of sherry given as gifts to nurses at the eye unit, though rumour did have it that she was ‘fond of her drink’ and took the bottles home with her, whereupon they were never seen again.

‘Please take it,’ Mrs Pearlman said, clutching my hand and curling the watch into my palm. ‘You will make an elderly lady very happy. I want you to have it.’

I smiled and nodded awkwardly, slipping it into my pocket before thanking Mrs Pearlman politely and wishing her a good night. As I walked out of the ward I felt very uncomfortable. I imagined Matron striding up to me, her X-ray eyes zooming in on the gold in my pocket. ‘Explain yourself!’ she would bellow, I was sure of it. What if she thought I’d stolen the watch from Mrs Pearlman? My blood ran cold, and I decided to drop by Sister Barnes’s office on my way out, to ask her advice.

When I laid the watch on the table before Sister Barnes, I felt instant relief. ‘I didn’t want to offend her, but now I don’t know what to do,’ I explained.

‘You’ve done exactly the right thing in coming to see me,’ Sister Barnes smiled. ‘A small box of chocolates at Christmas is one thing, but a gift like this is something else. Your instincts are quite correct. I’m afraid you will have to return the watch to Mrs Pearlman and explain that, although you are very touched by her generous gesture, it is against the rules to accept gifts from patients, and you are sure she will understand that you do not wish to get into trouble.’

I exhaled rather more loudly than I meant to, releasing my stress.

‘How are you getting on?’ Sister Barnes asked thoughtfully.

‘Fine,’ I said.

‘Just fine?’ She raised an eyebrow quizzically.

‘Yes, it’s just … it’s harder than I thought it would be.’

‘I remember thinking the very same thing when I was your age,’ she replied. ‘You need to believe in yourself more. I think you have what it takes, but do you?’

I felt very small and meek besides Sister Barnes. My shoulders were hunched, my chin was lowered and I felt washed out with tiredness. She, on the other hand, looked vibrant and full of life. Her eyes were twinkling, and she had an energy about her that made me want to straighten my spine and pull my shoulders back.

Sister Barnes eyed me thoughtfully and then stood up and clapped her hands together twice, as if struck by a bright idea.

‘Come with me,’ she said cheerfully. ‘Wash your hands and put your apron back on. I have a patient who needs an injection, and I think you are exactly the right nurse for the job.’

My heart leapt. I’d been desperate to give someone an injection ever since I arrived, but until now the opportunity hadn’t presented itself. Sister Barnes was young enough to remember how much it means to a young student nurse to be trusted with a syringe and a vial of drugs for the first time. I was thrilled.

As soon as I saw the patient in question I allowed myself a wry smile, remembering Linda’s description of the whale-like patient who was her first ‘victim’. Mrs Butcher was the female equivalent and I knew exactly why clever Sister Barnes had decided to let me loose on this particular patient.

‘Mrs Butcher, Nurse Lawton is here to give you your injection,’ Sister Barnes announced as she pulled the curtain around the bed and asked Mrs Butcher to lift her nightdress and present her right buttock.

‘Is it the first time she’s given an injection?’ Mrs Butcher asked, surveying me suspiciously, no doubt because I looked so young.

‘Not at all,’ Sister Barnes replied. ‘This is a demonstration to show how proficient Nurse Lawton is.’

Mrs Butcher sniffed and rolled over clumsily while I reminded myself to seek out the upper, outer quadrant of the buttock as I’d been taught during our practice on oranges in the classroom. Moments later, I pushed the needle through Mrs Butcher’s extremely well-padded rump and administered the drug steadily, with surprising ease.

‘All done!’ I said triumphantly. I tingled inside. I felt absolutely fantastic.

‘Didn’t feel a thing!’ beamed Mrs Butcher, her face cracking into a satisfied smile.

‘Thank you, Nurse Lawton,’ Sister Barnes said. ‘Now you can pop back in on Mrs Pearlman before you finish for the day.’

I wanted to skip down the corridor, I felt so exhilarated. I didn’t, of course. I walked on the left-hand side, as always, but there was a different rhythm in my step. It felt as though I was bouncing along on fluffy carpets instead of stepping purposefully on the hard stone floor, and I was pretty sure my eyes were twinkling just like Sister Barnes’s.

By now, we student nurses had been working flat out for about ten months. Nights out were rare, as we were usually either working, studying or sleeping, but that weekend Linda and I went to a dance at the university. We wore red and yellow mini skirts that Cynthia Weaver had helped us make, after we each bought a strip of fabric in Debenhams. We’d discovered that Cynthia was a very talented dressmaker, making every stitch of her clothing by hand, which is how she managed to always be in the latest fashions. On her advice we teamed the skirts with floral blouses, and I wore my hair in two long plaits, secured with velvet ribbons. As a final touch I doused myself in a generous splash of my favourite perfume, Estée Lauder’s Youth Dew, cramming the turquoise bottle into my tiny macramé handbag so I could refresh it later.

Strictly speaking, you had to be a university student to go to the dances, but we never had any trouble getting in. Some of the young male students wolf-whistled or messed about making saucy remarks about needing bed baths when we told them we were nurses from the MRI, but it was just light-hearted banter. The students were always happy to help get us in, and would leave us to our own devices once we were through the door.

Sipping orange squash between dances, Linda and I sang along to our favourite records, ‘I’m Into Something Good’ by Herman’s Hermits and ‘Bus Stop’ by The Hollies. During the evening we gently unloaded on one another too, swapping tales of forgotten bedpans, muddled-up meals and grumpy consultants who mostly seemed to be cast from the same mould and thought the rest of us should treat them like gods.

In contrast, the university students looked as though they didn’t have a care in the world. It was as if they had never left school, yet here were Linda and I, on a night out and letting our hair down, yet not quite able to forget about work: the business of life and death.

‘So you haven’t managed to kill anyone yet?’ Linda asked me jokingly, at which I flinched.

‘Not quite,’ I stuttered.

A month or so earlier I’d had a dreadful experience when I was thrown in at the deep end on one of my first night shifts. I’d pushed it out of my head, but Linda jogged it right back to the forefront of my mind.

‘You have to tell me now,’ she laughed. ‘It’s written all over your face!’

‘It was awful,’ I said. ‘I can’t believe what happened. I’ve tried to blot it out!’

‘Go on!’ she said. ‘Get it off your chest.’

‘OK,’ I said reluctantly. ‘Here goes. I was looking after a man called Stanley James, and Sister Craddock had given me strict orders to keep an eye on his fluid intake. He was only allowed an ounce of water hourly, as he was due an operation the next day, and you know what a stickler she is for the intake and output charts.’

Linda rolled her eyes and nodded.

‘He begged me for more water but I told him he had to do as Sister ordered, and eventually he settled down to sleep.

‘I didn’t hear him stir for a while, but when I went to check on him in the early hours I found his flowers on the floor and the empty flower vase in his hands. He looked at me apologetically and said, “I just needed a drink, Nurse.”’

Linda gasped. ‘He’d drunk the flower water? Oh my God! What happened to him? Did sister blow her stack?’

‘She did. I was as terrified of what she would say as I was of what would happen to Mr James. Anyhow, I managed to aspirate most of it back up, but I had to confess all in my report. When Sister Craddock read it, she yelled at me: “He’s a very poorly man and you’re supposed to be keeping an eye on him.” She was so angry her face went red and it made her freckles join up into one big freckle. She kept shouting, “You obviously weren’t keeping an eye on him properly!” I thought she was going to suspend me.’

‘What happened to Mr James?’ Linda asked, eyes bulging.

‘He died the next day, unfortunately,’ I said. ‘Apparently he was a dreadfully ill man and it was unlikely he would have survived for very long, even after the op. That’s what Sister Craddock said once she’d calmed down. She was surprisingly understanding, in fact. The flower water wasn’t what killed him and she wanted to make that very clear. So to answer your question, Linda, some of my training has been a baptism of fire, but I haven’t killed anyone yet! And I’m very glad that Mr James got his last drink before he died.’

We linked arms and walked home at 10.45 p.m. on the dot, to be sure to get in before the 11 p.m. curfew, as the Student Union where the dances were held was on the far side of the vast university campus, about half a mile from the nurses’ home. The roads were quiet as usual, save for the occasional Triumph Herald and Hillman Imp that drove by. One cocky young motorist with a head glistening with Brylcreem gave us an admiring wolf-whistle and the offer of a lift, but we politely declined. We broke into fits of giggles as we watched him pull away, leaning over the passenger seat to wind up the window manually, which was impossible to do with any style.

A few students walked in front of us, merrily swaying and singing the song ‘We’re All Going on a Summer Holiday’. I’d seen the film with Sue at the Stalybridge Palace when it first came out in 1963, and I’d been a big Cliff Richard fan ever since. Graham had even taken me to London to see him in concert with The Shadows at the London Palladium. Watching the students, carefree and clad in brightly coloured drainpipe trousers and winkle-picker shoes, took me right back in time.

‘Look at them, they think they’re on Carnaby Street!’ I joked to Linda, nodding towards the students. She asked about my one and only visit to the capital and I enjoyed reminiscing about it.

I told her Graham and I had gone on a North Western coach from Stalybridge and stayed in a twin room at a rather seedy hotel near the Palladium, though of course we never ‘did’ anything in the bedroom. Instead, we dutifully went to see the guards at Buckingham Palace and walked hand in hand along Downing Street to pose for a photograph with the policeman outside Number Ten, which every tourist did back then before security was tightened up and the road was sealed off.

After that we strolled along Carnaby Street, admiring the fancy window displays and ultra-fashionable shoppers. London girls wore similar clothes to us – mini skirts, babydoll dresses with matching coloured tights, kinky boots and ‘Twiggy’ shoes with fancy buckles – but everything seemed exaggerated, somehow. The colours were brighter, the skirts shorter, the belts wider and the shoes shinier – or at least that’s how I remembered it. My eyes were on stalks the whole time, and Graham’s eyes nearly popped out of his head when he saw the prices of the clothes at the men’s outfitters Lord John, as they were far more expensive than in Manchester.

The concert was really great. A kindly usher noticed that Graham and I didn’t have a very good view from up in the gods and offered to move us nearer the front. Our new seats were practically on the stage, and when Cliff began to sing I felt as if he was singing just for me. It was very hot and quite stuffy, with dry ice and cigarette smoke filling the air, and by the end of the evening my mustard and black smock dress was thick with perspiration, not to mention the pungent smell of Capstan and Park Drive cigarettes. Graham was so hot he had to remove his tweed jacket and skinny-striped tanktop, but Cliff somehow remained cool and impeccably presented in his sharp-cut suit throughout the show. I adored him!

‘We’re All Going on a Summer Holiday,’ the students on Oxford Road continued to sing badly, jolting me sharply back to this Manchester night in the summer of 1967. I envied the students’ freedom, their joie de vivre. Just a year or so earlier I had left the Palladium singing that song without a care in the world, just like them. Now life had become much more serious, even though I was still only nineteen years old.

‘I guess we all have to grow up some time,’ I remarked to Linda wistfully, ‘but I feel so old compared to those students!’

‘Hey, we’re still “Young Ones”,’ she joshed, recalling another Cliff song, but I think she knew exactly what I meant. We were young, of course, but as student nurses we were no longer carefree.

Chapter Four

‘People are dying … This is harder than I thought’

One morning about twenty student nurses in my intake assembled in the hospital car park and clambered onto a coach with Mr Tate. Our destination was Booth Hall Children’s Hospital in Blackley, north Manchester.

I knew it had a reputation for being one of the finest children’s hospitals in the country, and I hung on Mr Tate’s every word during the journey as he explained how Humphrey Booth first opened the infirmary in 1908, caring for the sick and destitute from the workhouse after the devastation caused by the plague. In 1914 it took in wounded soldiers from the First World War, and when war was declared a second time the hospital relocated its existing patients and installed a decontamination unit to treat victims of gas attacks.

‘Fortunately for the region, the anticipated casualties never materialised and within six months Booth Hall reverted back to caring for sick children,’ Mr Tate said. ‘The inscription on Humphrey Booth’s headstone reads “Love his memory, imitate his devotion”, and I think you will all agree that is an excellent standard to aspire to.’

I felt quite emotional as the coach pulled into Booth Hall. It was a privilege to be a part of the NHS, continuing the good work of the likes of Humphrey Booth, and I was eager to learn about caring for children. I imagined it would be a worthwhile and rewarding branch of nursing, looking after little ones and then returning them, fit and well, back to the bosom of their family. Maybe I might think about being a children’s nurse in the future?

It was windy as we walked across the car park to the hospital entrance, where a smiling but straight-backed Matron stood resplendent in a thick cape, arms held wide and welcoming like a priest on a pulpit addressing the congregation.

‘Welcome to Booth Hall,’ she enunciated with immense pride. ‘My staff and I are very pleased to have the opportunity to show off our fine hospital. I hope the visit will serve as an inspiration for you all, girls.’

I caught a glimpse of Linda, who was trying hard to suppress a giggle. ‘What?’ I whispered.

‘Mr Tate,’ she said, flicking her eyes over my shoulder.

I turned and saw our tutor grappling unceremoniously with his comb-over, which had become unstuck and was flapping wildly in the breeze, revealing his bald, shiny scalp in all its glory. The escaped hair must have been at least a foot long in full flight.

‘Linda, you are awful,’ I said. ‘Poor Mr Tate!’

We were taken on a whistle-stop tour of several wards and day rooms, which I was heartened to note had colourful bedclothes and curtains and bright pictures on the walls. Children wrapped in dressing gowns and slippers sat quietly with nurses, playing with wooden farmyard animals and train sets. I’d like to do that, I thought.

Our final stop was the burns unit. The smell and stiflingly high temperature hit me as soon as we stepped through the door, and my head immediately started to spin. In here, children were undressed save for their underwear and bandages wrapped around legs, arms, torsos and heads. There was a sickly-sweet smell of flesh mixed together with a petrol-like odour.

Sister Pattinson, who was in charge of the burns unit, patiently started explaining how burns were dressed with open-weave gauze impregnated with Vaseline, which was designed to stop it sticking. I thought how cool and composed she appeared – or was that just in comparison to me? By the time Sister Pattinson got up to the bit about placing the gauze very delicately over the wound so as not to cause more damage to the raw flesh, I was feeling hot and flustered. I was fainting, in fact, and I couldn’t stop myself.

I remember hearing the scraping of chair legs and the words: ‘Put your head between your legs, Nurse Lawton,’ as the ward began to swirl around me. Then I blacked out.

‘Never mind, Linda. Happens to the best of us,’ Lesley Bennyon told me back at the MRI the following evening, when we signed in for a night shift together.

‘I just felt so stupid,’ I said. ‘What must the children have thought? They are such brave little souls, and there’s me, with nothing wrong, collapsing like that in front of them.’

‘Put it behind you,’ Lesley advised. ‘Onwards and upwards! Come on, let’s see what’s in store tonight.’

Glancing down the ward, I noticed that Mrs Pearlman was fast asleep, which was unusual at the start of a night shift. The night sister had not yet given me my orders, so I walked over to Mrs Pearlman to check on her. She was very still and very quiet, and her black hair had fallen messily across her face. Strands of it were lying across her nose and mouth, and as I got closer I held my breath. Her hair was as still as she was. There was no breath coming from either her nose or her mouth.

I reached for her wrist. There was no pulse, and my own heartbeat quickened, as if to compensate. I smoothed her hair neatly off her face, and pulled the curtain slowly around her bed.

‘Lesley,’ I said, tears starting to well in my eyes. ‘Mrs Pearlman is dead.’

Half an hour later, Lesley and I were tasked with the job of laying out Mrs Pearlman’s body. Lesley was an old hand at this by now, but it was my first time and I didn’t mind admitting I was a little frightened.

‘I don’t know what to expect at all,’ I told Lesley. ‘I’ve never seen a dead body before, let alone touched one.’

‘We’ll work together,’ Lesley said. ‘It’s not half as bad as you might think.’

I nodded, silently asking God to help me in my job, and to take good care of Mrs Pearlman.

‘She was a very good lady,’ I said, telling myself she had lived to a ripe old age and appeared to have died in her sleep, which was a blessing. I guessed that Mrs Pearlman might have anticipated her death, and that is why she’d wanted to give me her gold watch. She was preparing to leave. ‘She deserves the best possible care. Please, God, help me to work well, and please may she rest in peace,’ I said silently.

Lesley had fetched a trolley upon which she had placed a basin of water, some cloths, cotton wool, bandages and fresh white sheets. There was also a label attached to a piece of string.

‘First we have to wash her,’ Lesley said quietly, dipping the cotton wool in the water and setting to work, delicately wiping Mrs Pearlman’s face. There were some faint smudges of mascara below the old lady’s eyes and some spittle around her mouth, which Lesley tenderly removed.

‘There we are,’ Lesley said brightly. It was almost as if Mrs Pearlman were still alive and Lesley was chatting to her as she gave her a bed bath.

For a moment I had to remind myself that Mrs Pearlman was very much dead. I stared at her face and could scarcely believe she could no longer talk or smile, because she looked for all the world as if she were in a deep sleep and might wake up at any moment.

Lesley caught my eye. ‘Let’s pop her teeth back in, shall we?’ she said, reaching for Mrs Pearlman’s dentures.

I’d been taught the theory of laying out a patient in school, but putting it into practice was another thing entirely.

Lesley opened Mrs Pearlman’s mouth gently and inserted the false teeth effortlessly, before flashing me a sympathetic smile. ‘There now, she looks better already,’ she said. ‘Once, I had to lay out a man whose body was cold and rigor mortis had started to set in. It took the strength of two of us to prise open his jaw and squeeze his dentures back in place!’

I smiled gamely, and Lesley kept talking. ‘How about we pop a little label on her toe?’

Lesley picked up the brown label upon which she wrote ‘Moran Pearlman’ and her dates of birth and death. I calculated she had been seventy-six years of age, and was glad she had lived a long life. ‘Here, Linda, this needs tying around her big toe,’ Lesley said, placing the label in my hand and giving me a nudge of encouragement as I got to work.