Полная версия

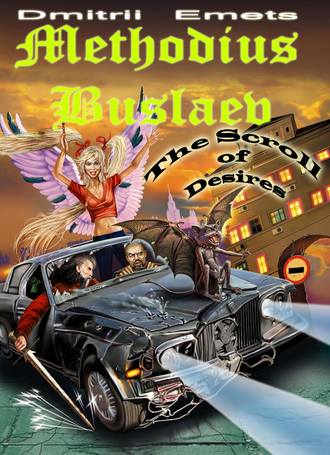

Methodius Buslaev. The Scroll of Desires

Essiorh started to seethe with indignation. He aimed a reproachful finger at Daph and was about to continue the disclosure, but unexpectedly stopped short. “Eh-eh… What day of the week is it today?” he asked absent-mindedly. “Monday,” announced Daph with doubt. She knew the moronoid days of the week rather poorly. “Yes, exactly. It was Monday morning, since the agents trooped over to Ares,” she added, after thinking it over.

Essiorh held his head. “Oh, woe is me! I mixed up everything! Having travelled here from the Transparent Spheres, I didn’t consider the difference in Earth time, didn’t think about the natural celestial lead, and warned you about an event, which hasn’t yet occurred, thus destroying the immutable law of freedom of choice.” Here Essiorh, not sparing his body, hit himself hard on the forehead with one of the rings. He did this with such zeal that an imprint appeared on his forehead. “Now I’m forced to take leave of you! But remember what I said to you!” he stated and started to move back hurriedly, clearly intending to disappear.

“Stop!” Daph shouted. “But was it you in the limo? May I use the informal ‘you’ or is this impudence?” The keeper stopped. “Informal ‘you’? This is impudence, but you may,” he said after some wavering. “Where, where was I?” “In the car following me. Well, tell me, this is important to me! Why were these tricks necessary? In order to play a little on my nerves?”

Essiorh looked at her in bewilderment. “Well, it’ll be known to you: I found you only twenty minutes ago. Found with the help of that indissoluble tie, which always exists between a guard and his keeper. I was in shock. I’ve become a complete stranger to the mortal world. I was last here during the times of ancient Babylon. I remember I found a whole crowd of idlers and, in order that the people would not lounge around with nothing to do, I proposed to them to build a tower. The usual small tower. Who knew that the moronoids would get so carried away? My boss was very unhappy.”

“Fine, not you, so not you. But did you see the limo?” Daph continued asking. “No. I must assume you have in mind one of those vehicles with a nice young woman at the wheel attempting to knock me down when I was pondering something on the pavement?” Essiorh tried to be more specific. Daph looked searchingly at him and decided that it was possible to believe his words. That Depressiac related to Essiorh benevolently served as an influential argument in favour of Essiorh speaking the truth. Taking into account its specific character, of course. In any case, it did not strain itself and did not hiss at him as at the limousine. “It means, not only are the golden-wings and the keeper from the Transparent Spheres interested in me… I’ve become popular. Only this form of popularity somehow is not much to my liking,” decided Daph.

“Why haven’t you been in the mortal world for so long?” Daph asked, after deciding to appear attentive. It would seem the innocent question embarrassed Essiorh. “After the Babylonian incident I began to have trouble at work… Eh-eh… I was slightly in the wilderness when you appeared. And here they remembered me,” he drawled evasively, staring at his very strong mitts with polite informative interest.

“Could nobody be entrusted with such an important issue? I have me in mind.” Daph was filled with enthusiasm. Essiorh smiled with a forced smile. Someone who recently fell from a chair and now attempts to present this as a joke would smile so. “Oh no. I fear that the issue is much simpler. No one else agreed to take you… All shoved you aside as they could. Finally, they found the last one. Alas, this last one turned out to be me. You and I, as the moronoids very rightly say, are worms from the same coffin.”

“What, what? Peas from the same pod?” “Worms from the same coffin!” Essiorh obstinately repeated. “And don’t argue! So they say. I read it in the dictionary, when preparing for transplanting to the human world.” “Ah, I understand! Sniffka said that Guards of Gloom cast an evil eye on one publication of the moronoid phraseology dictionary. Her good friend, having found out about this, immediately purchased twelve copies to give away to friends. So here, according to Murphy’s Law, he miscalculated, Sniffka turned out to be his thirteenth friend and didn’t get this dictionary. She was very hurt!” Daph elaborated.

Essiorh turned a deaf ear to her words, thinking about something. “Daphne! I have a request for you… a personal one… I’m asking you not to tell anyone that I showed up with my reproach sooner than I should have. We’re very strict about this, taking into account that I also have earlier blunders. Can I hope that everything will remain between us?” Daph nodded patronizingly and slapped her keeper on a shoulder solid as granite. “Have no fear! I’ll sew a zipper on my mouth and zip it shut every time I try to squawk… Depressiac is also a reliable lad. Except for a good fight, night flight, and Persian cats, he has no other weaknesses. And also no interests, by the way, if we don’t consider raw meat.”

Someone had already been drumming nervously for a long time from within the iron door accidentally welded shut by Essiorh’s reproach. It no longer made any sense to remain in the entrance. Daph and Essiorh left, not waiting for the moronoids to summon the Emergency and Disaster Relief Ministry or the fire department.

Twilight slowly thickened above Moscow, exactly as if someone had dimmed the brightness of a monitor screen sequentially. The wind played on an unglued advertisement. Automobiles with maniacal perseverance rushed along the ring of boulevards. Their drivers diligently made a show of having important business somewhere. And, it goes without saying, none of these simulators of stormy activity, masters of beating the air, was concerned that here, two steps away from them, Daphne the guard of Light was discussing the fate of the moronoid world with her keeper from the Transparent Spheres.

Suddenly Depressiac emitted a warning guttural sound. Daph looked up. She felt a sharp uneasiness. While she was in the entrance, something changed in the magic field above Moscow. Neutral and sluggish earlier, now it blazed like the aurora borealis. Daph scrutinized the sky over the roofs of the houses. It seemed to her that to the right, somewhere very high, two golden points flickered. Before Daph had time to focus on them, the points disappeared. Almost immediately in another part of Moscow, somewhere awfully far away, in the outskirts, an additional point flickered. It traced a semicircle and also disappeared. The points resembled not even sparks but timid yellow maple leaves, when in the evening murky forest the last ray of the sun suddenly falls on them.

“Golden-wings. There are about two scores of them above the city. They appeared about ten minutes ago,” Essiorh announced with knowledge of the matter, answering her unvoiced question. “What are they doing here?” Daph inquired with uneasiness. “Hmm… Strange question. They’re searching, of course.” “For me?” “This time it’s not you. Although, if they catch sight of you, there’s no doubt they’ll immediately attack you. So, no noticeable magic. Be quiet as a dead mouse in the fourth power generator… Ouch, again the jinxed dictionary! But now, if you’re interested, look over there… Over that house on the corner, found it?” “No.” “Look closer. Higher than the billboard, higher than the attic… Do you see a fat black blob? Well!”

Daph looked hard and actually saw what Essiorh was talking about. In the air, a round-shouldered little fellow in a raincoat was leisurely moving away from them. He was going along and piercingly examining the walls of the houses. Obstacles did not exist for his small colourless eyes. Neither concrete walls nor iron roofs – nothing could cover or hide. The small sticky hand would reach out to everywhere. The sticky fingers would close over the most important and the most secret. On an adjacent street Daphne saw yet another figure exactly the same. And another one. And another. The figures were moving in parallel, block after block combing the city.

Daph grabbed the collar of the cat dashing from her shoulder and a spike in the collar pricked her finger. “Who are they? Darts of Doom?” she asked indistinctly, licking her wound. Essiorh, puzzled, looked sideways at her. “What guards? Don’t amuse me! Ordinary agents. Hundreds of them all over the city, but all the same the agents have to be careful. Golden-wings are not in the mood nowadays. They attack continually.” “Really?” “I don’t lie without sound reasons!” Essiorh was insulted. “And guards of Gloom don’t protect their agents?” “Whatever for? What are such agents to Gloom, dozens of races flattened and banished to Tartarus? Gloom has never particularly spared clay and plasticine. By the way, are you aware that some recently prepared agents even have blood? We discussed this at briefing. Their blood is the powder for office printers diluted with Troika cologne or ethyl alcohol. Ligul mocks the image and likeness any way he wants…” Essiorh said with bitterness.

Unexpectedly he turned sharply, caught Daphne by the elbows, and quickly carried her under the arch. Moronoids eyed them with alarm. Some heroically disposed men even came to a halt. Daphne, as soon as Essiorh put her down on the ground, waved her hands, showing that everything was in order and no one was attacking her. “Quiet! Certainly no one can cut into the conversation of a keeper and his charge, but nevertheless it’s better not to be noticed!” Essiorh whispered, pressing against the wall and carefully looking out of the arch.

Daph saw how a round-shouldered agent in a raincoat suddenly tossed up his head, looking out at someone, then stooped, drew himself together, and in a cowardly manner dived into the attic window. Almost immediately, a bright flash drew a line in the sky. Above the street, something, impossible to see with moronoid sight, rushed past in a golden radiance. Dazzling wings and a stern profile flickered, prolonged by a flourish of the flute.

For a while the golden-wings obviously pondered whether he should continue pursuit along the back alleys with attics and sewers, which creations of Gloom so loved, and then, after reconsidering, rushed after another agent, the one combing the region from the area above. The agent, down on his luck and losing his head, rushed along the boulevard from one signboard to another and only at the last moment, escaping from maglody attack by the guard of Light, desperately dived with his plasticine head into the sewage grid for rainwater. He dived, sunken into liquid clay there, and was hidden.

The golden-wings gained altitude and disappeared behind the flat roof of the cinema. After ascertaining that danger had passed, the agents came out of their refuges, shook, somewhat restored their flattened forms – especially the crumpled one squeezing himself through the grid, and continued to comb the city.

“What are they doing here? Both agents and golden-winged? Why so many of them?” Daph asked with apprehension. “Searching. Both these and others. Only here, for some reason I believe more in the intrusiveness of plasticine villains,” Essiorh remarked sadly. “And the agents are not searching for me?” Daph asked just in case. Essiorh looked at her with compassion. “My good child! Are you at this again? As they once told us at briefing: the double repetition of a question indicates either depressive sluggishness or maniacal suspiciousness. Why would Gloom search for you when you’re already with Ares? No, they need something else,” he explained, with his tone showing that he was not about to explain what this something was.

“Fine, don’t tell. But can we play a little game of hot and cold?” Daph quickly asked. “You may. But I promise nothing,” emphasized Essiorh. “It goes without saying. Perhaps they need, by chance, that scroll, on which the impression of my wings would be found?” Daphne asked. “I’ve said too much,” the keeper growled. “What value does the scroll have? Why is it so necessary to Gloom? Essiorh, don’t be stubborn! Why hide from me what’s already known to all?” Daph quickly asked.

The guard-keeper was perceptibly embarrassed. The secret had turned out to be somewhat painfully transparent. Nevertheless, he continued to persist, “Time for me to go. We’ll still meet! Till we meet again! And don’t be offended! I can’t, I simply don’t have the right…” After nodding to her, Essiorh quickly jumped out of the arch. His prompt retreat resembled a flight. When, coming to her senses, Daph rushed after him, the street was empty. Only the wind was rocking the “No parking” sign suspended from a wire.

Pondering over the strange events of the day, Daph slowly wandered towards Bolshaya Dmitrovka. In a minute, not a single suspicion was left. Suspicion had strengthened little by little and changed into truth. The truth included the fact that her guard-keeper was a chronically unlucky wretch. “The most muddle-headed guard of Light simply by definition must have the most spontaneous keeper. Everything is logical. Don’t you think, huh?” she asked, turning to Depressiac. However, the cat was thinking about the dog across the street, sufficiently far from them. It was moving extremely insolently, holding its tail curled up, barking at cars, and ambiguously sniffing posts. Daph had to hold Depressiac tightly by the collar to end the discussion.

Chapter 2

Grabby Hands

Methodius kicked the chair in irritation. For a solid half-hour, he had been trying with mental magic push to light the candle standing on the chair some a metre away from him. However, in spite of so small a distance, the candle persistently ignored him. Then when Methodius got mad and attempted to put everything connected with this failure out of his head, the candle fell and in a flash became a puddle of wax. Moreover – what Buslaev discovered almost immediately – the metallic candlestick also melted together with the candle.

“I don’t know how to do anything. I’m a complete zero in magic. I have it either too weak or too strong. And I’m this future sovereign of Gloom? All of them are delirious! Better if Ares would teach me something besides slashing with swords!” Methodius grumbled, rewarding the chair with one more kick. The chair went off along the parquet for half a metre, wobbled several times in pensiveness, and changed its mind about falling.

Despite the fact that July was no longer simply looming on the horizon but literally dancing a lezginka on the very tip of the nose, Methodius, as before, was living in the Well of Wisdom high school, where annual exams had not yet ended. Vovva Skunso, having grown quiet, did not allow himself to play any tricks and was as polite as at a funeral.

The director Glumovich greeted Methodius every time he saw him in the hallway, even if they had met seven times in the day. At the same time, Buslaev constantly felt his sad, devoted, almost canine look. On rare occasions, Glumovich would approach Methodius and attempt to joke. The joke was always the same, “Well now, young man! Tell me your confusion of the day!” Glumovich said in a cheerful voice, but his lips trembled, and his forehead was porous and sweaty, like a wet orange. Every time Methodius had to exert himself in order not to absorb his fuzzy dirty raspberry-coloured aura accidentally. Nevertheless, Glumovich did not ignore exams, and it was difficult for Methodius, frequently letting his studies slide in previous grades. For the most part, it helped that even without him there were enough meatheads among Well’s noble students. Nature, having succumbed to a hernia in the parents, was making merry to the maximum in their children.

After throwing the damaged candlestick – it had not yet cooled and still burned the fingers – into the wastebasket, Methodius left the room and set off aimlessly wandering around the high school. The soft carpeting muffled his steps. Artificial palms were languidly basking in the rays of a florescent light. There were practically no students in the hallways. In the evenings, the parents dropped by to pick up the majority of them, and then on the other side of the gates by the entrance would line up a full exhibition of Lexus, Mercedes, Audi, and BMW. The Wisdom Wellers were usually more or less lacking in imagination. Waiting for their young, the padres of well-known last names winked slyly at each other by flashing signal lights and honking horns, greeting acquaintances.

Methodius slowly made his way along the empty high school corridors and, for something to do, studied photographs of earlier graduates, read the ads, the timetables, and in general everything in succession. He had long ago discovered in himself a special, almost pathological attachment to the printed word. In the subway, the children’s clinic, a store – everywhere boring for him, he fixed his eye on any letter and any text, even if it was a piece of yellowed newspaper once stuck under the wallpaper.

Here and now, he was interested in the amusing poster by the first aid station. On the poster was depicted a red-cheeked and red-nosed youth lying in bed with a thermometer, either projecting from under his armpit or like a stiletto piercing his heart. A white cloudlet with the following text was placed over the head of the youth, “Your health is our wealth. At the first sign of a head cold, which can be a symptom of the flu, immediately lie down in bed and stick to bed rest. Only this way will you be able to avoid complications.” Instead of an exclamation mark, the inscription was crowned with one additional thermometer, brother of the first, with the temperature standing still at 37.2.

Methodius instantly assessed the originality of the idea. He practically could always simulate a head cold. However, in half of the cases even a simulation was not necessary. “Eh, pity I didn’t know earlier! Must say I’ve ruined my health! How many school days spent in vain… But it won’t work with Ares, I fear! Can’t dodge the guards of Gloom with a head cold!” he thought and began to go down the stairs.

Soon Methodius was already on Bolshaya Dmitrovka. House № 13, surrounded by scaffolding as before, did not even evoke the curiosity of passers-by. A normal house, no more remarkable than other houses in the region. Methodius dived under the grid, looked sideways at the guarding runes flaring up with his approach, and, after pushing open the door, entered. The majority of agents and succubae had already given their reports and taken off. Only a vague smell of perfume, the stifling air, the floor spattered with spit, and heaps of parchments on the tables showed that there had been a crowd here recently.

Julitta looked irritated. The marble ashtray, which she had used the whole day to knock some sense into agents’ heads curing them of postscripts, was entirely covered in plasticine. Aspiring to cajole the witch who was losing her temper or at least to redirect the arrows, the agents told tales about each other. “Mistress, mistress! Tukhlomon is playing the fool again,” one started to whisper in a disgusting voice, covering his mouth with his hand. “Where?” “Hanging over there.” Julitta turned and made certain that the mocked Tukhlomon was in fact hanging on the entrance doors, with the handle of a dagger sticking out of his chest. His head was hanging like that of a chicken. Ink was dripping from his half-open mouth. This nightmarish spectacle would impress many, only not Julitta. “Hey you, clown! Quickly put the tool back where you took it from and come up to me! I counted to three, it’s already four!!!” she began to yell.

Tukhlomon, squinting like a cat about to be punished with a sneaker for bad habits, sadly opened his eyes, freed himself from the dagger, and on bent knees approached Julitta. The witch pitilessly and accurately knocked him on the nose with the heavy press of the Gloom office. The agent made a face feigning fatal and eternal offence, wiped his watering eyes, and after a minute was already twisting like a grass snake around Buslaev.

“How is the future majesty? Hands are not sweating?” he spitefully asked, squatting down. “And how are you? Don’t sneeze continuously at night, the conscience isn’t itching?” Methodius answered courtesy with courtesy. “Nothing. Thanks… It’s only you who sleep at night… We work at night as in the daytime! Please be good enough to see for yourself!” the agent answered. “Don’t kill yourself!” “I won’t. Be kind enough not to worry. For your sake I’ll look after myself,” Tukhlomon answered mysteriously. He giggled and took off, politely shuffling alternately with both feet.

Ares, as usual, was staying in his office. One could only go to him by invitation. The chief of the Russian division of Tartarus was there almost without budging – day and night. Only recently, warning no one, he disappeared somewhere for almost three days and then re-appeared suddenly, giving no one any explanation.

Next to Julitta Aida Plakhovna Mamzelkina found room for her own body. Aida Plakhovna’s cheeks were rosy and her eyes bright. She likely already had time to dip into the honey wine. Judging by the contented look of both, Julitta and Aida Plakhovna were busy with the most pleasant matter on Earth – slander. After putting her bony feet up on a chair, Mamzelkina looked through the far wall of house № 13, which was no obstacle for her all-seeing eyes. It was that brisk evening hour, when all kinds of two-legged upright-walking essences were hurrying somewhere or returning from somewhere. Moronoids were scurrying about along sidewalks, lanes, pedestrian crossings, and bridges of the megalopolis of ten million.

“Julitta, my dove not yet dead, look over there!” Mamzelkina cackled. “What a serious, dignified man! What kingly carriage! How he carries his portly body, how solidly and peacefully he looks in front of himself! See how everyone yields to his path! They must think that this is the prefect of the region going around his domain in search of something else to knock down! In fact, this is merely Wolf Cactusov, untalented writer and quiet hen-pecked husband, whom the wife has sent out for dumplings at the corner store. Isn’t it true how deceptive the first impression is? Interesting, how would this turkey sing if I remove the covers off my tool now?” “Perhaps we can check?” Julitta innocently proposed. Aida Plakhovna threatened her with a finger comprised, it seemed, of only some joints and bones. “Not supposed to. There was no order for the time being… My doe not yet shot, I don’t do unauthorized activity! I have an establishment! That’s that, my cemetery treasure!” Aida Plakhovna edifyingly said.

Julitta sighed so sadly that all around for one-and-a-half kilometres all gas burners went out, and leaned back against the chair. “Why so sad, dear? Feeling miserable?” Mamzelkina asked sympathetically. “Oh, Aida Plakhovna! I’m miserable,” complained the secretary. “Why?” “Miserable that no one loves me. In the evenings I get so tired of humanity that I want to nail someone.” “You, girl, drop this! Don’t lose control of yourself! There now, I see all your agents are walking around crippled! Don’t be heavy-handed and muddle-headed!” Mamzelkina said sternly.

She turned around and saw Methodius standing still by the doors, looking at her with curiosity. “Oh, and this, the little chick not yet slaughtered, is hanging around here! Everyone wanders around! I walk around the city, look along the sides. I have no strength! Agents prowl, golden-wings prowl – and everybody needs something! And now even this, young and green, was roaming! Well, why do you wander, dear, why do you stroll?” the old woman began to moan. Methodius muttered something unhappily. He had his own opinion regarding who was hanging around and who was quaffing honey wine.

Aida Plakhovna threw up her hands. “I dare say you’ve grown bolder, to talk to me so! I’ve heard much about your feats, heard much! Passed the Labyrinth, seized the magic of the ancients, but so far haven’t found the key to the force… Don’t grieve, big-eyes, everything will come together. What won’t come together will be hidden. What won’t be hidden will lie as dust. Gloom also wasn’t built in a day.” Methodius nodded impatiently. He did not like it when they hinted to him that sooner or later he would become the sovereign of Gloom. This was as intolerable as the flattery of agents and sweet giggling succubae.

Mamzelkina quizzically inclined her head to one side and started to move with such speed on a chair towards Methodius, as if the chair was mincing along on bent legs. “Why so sullen, huh? Is your spiritual pain troubling you? How’s your eidos, kinfolk? No grabby hands have reached it for the present? Watch, many such hands here, oh, many!” she moaned.