Полная версия

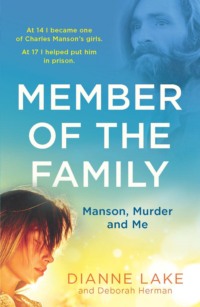

Member of the Family: Manson, Murder and Me

My father remained largely silent on the matter, but none of this eased his malaise. It’s hard to say exactly what impact his reading had on him, but there’s no doubt that it influenced him and enhanced his impatience. The Beats. Jazz music. These were the first sounds of the underground reverberating out from the coasts toward Middle America and making men like my father question the choices they’d made.

The tipping point came from something that seemed innocent enough. Somewhat impulsively, my father ordered a hi-fi, a high-fidelity stereo system, by mail. He couldn’t wait to get the thing—he thought it was going to fill the entire house with sound, in contrast to the little phonograph, music from which barely carried into the next room. But when the hi-fi arrived, he looked at the bill, apparently for the first time, and freaked out at the cost. Shortly after that, he broke from their usual pattern of letting my mother handle the finances and instead sat down with her while she was writing out the bills. He turned them over and read them one at a time, eventually stopping at the mortgage bill. As he stared at it, he figured out the interest on the mortgage, becoming more and more upset. Perhaps the mortgage became a symbol of his frustration with our situation. The perpetual responsibility, the way it tied us down in Minnesota, and the fact that our house and family would apparently be his life’s work—all of it seemed to weigh on him.

“How the hell are we going to keep up with these payments?” he shouted at my mother, who was surprised that he had suddenly started caring about the money they spent. His response might also have had something to do with the books he was reading, because he was telling her that they were being pulled into, as he put it, “the establishment trap of materialism.”

“This house and this stuff is going to steal our soul!” He slammed the bill on the table and knocked the other papers on the floor.

“It was your idea to get the hi-fi,” Mom shouted back. It was not really a shout, so much as a mix of utter surprise and confusion. She never raised her voice to him, because to her, he was always right. But his reaction was puzzling, even for her. She had never wanted the hi-fi in the first place. He’d wanted to play his music as well as records by people he had been reading about like Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg. He wanted her to spend time with him listening to them, but she always had her hands full and only feigned interest.

This debate over our mortgage and our “stuff” went on. My father held fast to the idea that the house was a problem for us, refusing to let it go. And in the end, he impressed my mother with what she believed was his sincerity about materialism. What my father really wanted, and which we’d seen glimpses of already, was to move to Berkeley, get his master’s degree, teach art, and paint. California was where it was happening, and that was where he wanted to be.

My parents put the house on the market, and instead of a Realtor or an actual buyer, one of the neighbors approached them about the house. My father was being very impulsive and wanted to get out from under the stress of the mortgage, so when they offered their travel house trailer as a trade, he and my mother agreed it was a clever idea. That was that. It wasn’t even considered a down payment. They simply traded this lovely home with the big lawn, room to play, and a greenhouse next door, on a handshake and a whim.

Like many decisions made during those years my parents just did it and that was that. It all happened quickly, and before the end of a year that had started out calmly enough, before Christmas of the year I was in second grade, we gave away most of our things, took what we could, like my toy sewing machine, and packed the trailer. We didn’t even have anyone to tell that we were leaving. We didn’t have family in the area and I just had my teachers and friends from school. My mom even had to leave her own sewing machine behind. On the day we moved, they hitched up the trailer to our car and we all got in, resigned to the fact that we would be headed west to California and to the new life my father craved, setting out for the promised land of California, like pioneers in a wagon train.

Except that’s not what happened. As we drove away, the car kept stalling. My father finally pulled over to the side of the road and got out. We stayed in the car, huddled together against the Minnesota wind, which penetrated fiercely through the windows. In the back seat I held baby Kathy close to my chest to keep her calm as I watched my father jiggle things under the hood of the car.

My mother was already sobbing and mumbling about how she would miss her sewing machine. She vested all her regrets on the one thing she couldn’t bear to leave behind. My father was cursing and stomping around, chain-smoking. I didn’t typically see my father this angry. Usually he would withdraw rather than yell. There were times when he was drunk when he would lose his temper, and I saw him hit my mother a few times. But this felt different. It was scary to watch as he unraveled. Clearly he was upset about more than an aborted trip to California. With this useless trailer came a useless dream and more disappointment than he was ready to accept.

As my mother continued to cry, I wished that I could calm her, but I had the baby asleep in my arms. Meanwhile Danny was surprisingly relaxed considering the histrionics happening all around us. My father saw her crying and yelled at her to stop blubbering, which only made her cry even louder. At this point I think she was just exasperated. Everything was happening so fast and she hated to be so out of control.

My parents eventually figured out that we weren’t going to be taking this trailer to California and found someone to tow us to the nearest trailer park, which was in a suburb south of Minneapolis called Burnside. Mostly dirt and mud, the trailer park was not really set up for permanent living, but we stayed where we landed, next to a few other trailers that must have met the same fate.

About twenty-three feet long and without many amenities, our trailer was not set up for such permanent living either. The five of us learned to squeeze into the small space, my father still chain-smoking in our tin-can home. The trailer had a galley kitchen and a living room, where we put the baby’s crib. Danny and I had bunk beds in the back of the trailer and my mom and dad had their own little room. We had a small living room area where we could play games at night and do homework. We had a potbelly stove at the entrance to the trailer, on which I could easily iron my hair ribbons. All I had to do was run them along the heated top and they came out wrinkle free.

We all did our best to settle into Burnside. My brother and I were enrolled at a funky little country school and had to take a bus, where I spent the second half of second grade and the first half of third grade. I got used to the situation, but my mom still missed her sewing machine. She never mentioned the house and her stove, but we all knew that she missed them as well. The impulsive trading of our house had been done with a handshake, and since we were not that far away, one day my parents went back for some of the belongings they’d left behind. But when they arrived, no one was home. The new owners were not just out for the day—it appeared they hadn’t been living there for a while. There were no belongings to reclaim, no house to trade back, and my parents had no one to blame but themselves. It wouldn’t be the last time my parents’ idealism was betrayed by reality, or the placing of trust in the wrong people. But that didn’t mean they’d learn from it.

We lived in the trailer park until my father found a patron of the arts to support his painting. He had been searching for someone to believe in his art for quite a while, so meeting this wealthy art-loving couple was the break he had been waiting for. They owned a gallery and asked my father to provide them with some paintings. When they found out about our living situation, they invited him to become a regular artist for them. They loved his style and couldn’t stand that my father was an artist without a studio or a proper home. The arrangement would be that he would provide them a certain number of canvases for the gallery to sell and he could work on other projects if they did not conflict.

Even more generously, this new couple set my father up with his own studio where he could paint and create, and placed us in a small house with a nice yard where we could live more comfortably. Kind as these actions were, they were also part of the patron’s role. Gallery owners were supposed to take diligent care of their artists. When word spread of their generosity, other artists would be enticed into joining their stable.

All of us loved our new little house, and once again it felt like home, but more important, it felt like home to my father, a place where he could pursue his art to his content. Gradually his fixation with moving to California abated, and life returned to some sort of normal. At least for a time.

2

FAMILY MATTERS

With my dad occupied painting for his patrons, our family settled into a routine of sorts, and he threw himself into his work. He spent the days in his studio, which was filled with supplies, canvases, and a drafting table. It smelled like a combination of linseed oil, India ink, cigarette smoke, and creativity. He smiled and listened to jazz records while he worked

Christmas Day during my third-grade year, when we lived in this little house, was the best time I can remember ever having with my entire family. That morning I awoke to the smell of fresh cinnamon buns that my mother had made from scratch and raced Danny downstairs to see what was under the tree. Beside the presents from Grandma, Grandpa, and my parents that had been under the tree the night before, there was a new one. There it was in all its glory, the Barbie Dreamhouse I had wanted—a gift from Santa Claus.

I ripped through my other presents, opening gifts from my father’s parents from Milwaukee. Our only close family, they would be visiting us in the summer now that we were settled into a proper home. Finally, I got to a present that was marked To Dianne, from Dad. I tore into the package and couldn’t believe what was in it. My father had made a bed for my Barbie to fit into the house that Santa had sent me. On the verge of tears with excitement, I went to hug my dad; always a bit awkward at affection, he turned away, giving me a sideways hug.

Later that day, we had a Christmas dinner with some of my parents’ friends. My parents had settled into our new home, our new life, and had added new people. My father had collected a new crowd matching the life he was creating and his new persona as a professional artist. Around the table this year was an Ethiopian artist who wore a dashiki. The dark-skinned man chewed on toothpicks made of orange sticks and used them to clean his teeth. He told us about how in his country they did not use forks and knives when they ate. Instead, he explained, they used a special bread to scoop food into their mouths and into the mouths of others sharing the table. This Christmas meal would be strictly American, and he was looking forward to our traditions. My parents were also friends with a Ukrainian couple who joined us. They brought us pysanky as a gift and explained that they were typically for Easter. These were eggs decorated with Ukrainian folk designs. The wife promised to show me how the eggs were created during the holiday.

It was a remarkably special day, but sadly it was also one of the last of its kind. We never were that happy and secure again in Minnesota. Things always had a way of changing, especially in a family like mine.

My parents seemed content with their friends, but my mother encouraged us to keep in touch with my father’s parents as well. Sometimes I would hear them arguing about having them come visit us, with my mother insisting it was good for children to know their family and my father saying he didn’t need to see his parents. During the summer between first and second grade my grandparents had come out to visit us back in our big old house. It was a fun visit, and I’d enjoyed having them around, eating meals together and going places. I was proud when during dinnertime one evening, my father hung a portrait he had painted of me on the wall for everyone to see. My dad and grandpa worked on the car together and we all seemed to get along.

Still, in the aftermath of the visit, there seemed to be some residual tension between Grandpa and my father. It was obvious that my grandparents didn’t share my father’s interests, and that Grandpa in particular never liked my father’s desire to be an artist, looking down on him for it. The following summer we didn’t see my grandparents, and I don’t think my parents ever let them know that we had been living in a trailer park. But now that we were back in a real house and my father was becoming successful, my mother began encouraging him to contact them again.

“The children miss their grandparents, Clarence, we should invite them out.”

“I’m too busy to take the time with them. Besides, I am finally enjoying myself,” he said. Father and son exasperated each other, which made it difficult for the two wives, who made it their mission to keep their husbands happy. Any tension that could not be relieved by copious amounts of beer would have repercussions for both women after dark.

“Your mother called and really wants to see Dianne. She said she will be all grown up before you know it. Your father agrees.”

“Well then, maybe she could go to see them,” he suggested.

“By herself?” Mom asked, not so sure she should allow my unsupervised independence. She had grown to love her mother-in-law, who had become something of a Rosetta stone to help her understand her son, but she still had reservations about sending her daughter so far away on the train.

“She’ll be fine, and we can have a break from at least one child for a few weeks. And it will get them off our backs for a while.”

And so, in the summer of 1962, when I was nine years old, my parents made plans for my visit to Wisconsin. When my parents told me I would be visiting my grandparents in Milwaukee, I wasn’t even scared of being by myself, just excited to have all the attention without my brother and sister being around all the time. I planned everything out. The first things I carefully packed were my Barbie and Ken dolls, along with the clothing I had sewn for them. I didn’t want to go on this adventure without them. Like me, my Barbie had red hair that she wore in a bouffant hairdo. I wrapped her hair in tissue so it wouldn’t get mussed during the long train ride. I dressed Ken in a makeshift suit so he would be properly attired for the visit. I also packed some of my favorite books, National Velvet and Nancy Drew, my hairbrush, and some Max Factor lip gloss my mom let me buy. It was shiny but tasteless, and it made me feel beautiful. Mom helped me carefully fold my clothes, as well as some pink clip curlers for my hair, a robe, and a pair of pink fluffy slippers.

When I got to Milwaukee, my grandma and grandpa met me at the station.

“You’ve gotten so big,” Grandma said. “You look so grown up since we saw you last.” It had been two years and I had been more like a baby during their last visit. Grandma pulled me into a hug against her soft chest; she smelled of a combination of lilac powder and beer.

Grandpa patted me on the head and grabbed my bag. He was about the same height and size as Grandma, but his arms were much stronger. The years of house painting had preserved a muscularity more common in a younger man. Now they owned an apartment building together and he did all the maintenance while Grandma collected the rent and kept the tenants happy.

When we got to the building, they gave me my own room across from theirs and Grandma helped me unpack. We put my Barbie, Ken, and books on the oak highboy next to the bed that they said used to belong to my dad. Then we carefully placed my folded clothes in the now-empty drawers. I thought about my dad’s clothes in those same drawers when he was a little boy. Sitting on the highboy was a framed picture of Grandpa and me taken during their last visit.

When we got settled, Grandpa and Grandma took me right across the street to a bar.

“Hey, Dutch,” Grandpa said, “two brews for us and a Shirley Temple for our little Shirley Temple.” I liked that they were showing me off. This would not be the only time that they took me to the local bars. They liked their beer and I liked my Shirley Temples. The room was smoky and dark, but I liked that they let me be in there with the grown-ups. The later it got, the louder they got. Then we walked home and Grandma helped Grandpa into bed.

That first night after I had gone to bed I heard Grandpa rustling around in the kitchen. I found him by himself at the small dinette with a glass of milk and a box of graham crackers. He crumbled the graham crackers into the milk until it was thick as pudding.

“You want some, little girl?” It looked lumpy, but I was happy he was offering me some of his snack.

“Sure.”

“Get a glass and I will show you how it is done.”

I poured some milk from the bottle in the Frigidaire and grabbed two graham crackers. “You got to have just the right number of crackers to make it good,” he explained. It seemed like a delicate operation, but I got it right the first time.

“You’re a natural,” he said. We spent the next twenty minutes in silence as we slurped down our graham cracker mush. “You ought to get back to bed. We are taking you to the zoo tomorrow.” I was so excited to go that I didn’t even plead to stay up later with him. I shuffled away in my pink shag slippers and went right to sleep.

The zoo was everything I’d hoped it would be, and I spent the next few days after that with Grandma, going to an elderly neighbor’s apartment to check on her and taking a trip to the salon, where I got a rather unfortunate perm. One morning at breakfast, Grandma told me that this day would be a bit different.

“You’re going to spend the day with Grandpa today,” she said, giving me a hug. “Be good and do what he says. I have some shopping and errands to do. I will be back for supper.”

I was eager to spend the day with my grandpa—watching TV, reading the funny papers, and crumbling graham crackers into our milk. We sat together on the couch for a while and I leaned my head on his shoulder. We were watching a Western. It was such a treat to watch a television that I didn’t mind that it turned out to be old Zorro reruns. Grandpa smelled like green grass. He wore a kind of aftershave called something like old bay rum. I could have stayed like that for hours.

“I have an idea for what we can do together.” Grandpa broke the silence.

“What’s that, Grandpa?” I replied excitedly. “Do you want to play Parcheesi?” We had been having a running competition.

“Let’s take a bath together.”

“A bath?” The idea seemed kind of strange. I had never taken a bath with my father or even my brother except when we were little.

“It will be great,” he added. “It is a natural thing to do and you will like it. It is how I like to relax.”

He turned on the faucet while I went to my room to put on my bathing suit.

“You won’t need a bathing suit in a bath. You can take off your clothes in here,” he added, gesturing for me to come into the bathroom with him.

When the bathtub was full, he took off his clothes and got in. Then he told me to take off my clothes and join him. I took off my shorts and top and folded them. I put them on the floor in the corner by the sink. The last thing I took off were my panties. I got in the warm water facing him and it felt good.

“See how relaxing this is.” He sat in the water with his eyes closed for a few minutes with his hands along the tub rim. I closed my eyes too but peeked out of one open eye. I watched him put his hands under the water. His breathing changed. It became deeper and faster. Then he opened his eyes and grabbed my hand. I barely moved.

“You know, Dianne, you are old enough now to know where babies come from.”

“I do know where they come from, Grandpa,” I proudly answered. “God puts a seed into the mom’s belly and the baby grows in there.” I thought I was clever to know this fact already. Grandpa laughed and held my hand more tightly.

“That is not how the seed is put into the mom, Dianne. There is more to it and I need to tell you the truth.” He stood up and his body looked different than what little I had seen when he got into the bath. His boy-part was big and he touched it with both his hand and mine. The skin felt warm and soft. When he began to move our hands over what he explained was what the man used to plant his seed in the woman, I pulled my hand away. I couldn’t picture that what he was saying was true. How could that go into what I believed was a very small hole?

He explained how the man and the woman would make the seed come out and then demonstrated with his hand. “It is just like blowing on a dandelion.” Then this milky liquid dripped out from between his fingers as he made a heavy sigh. It landed in the tub, so I didn’t move. I didn’t want to be near the seeds. He got out of the bathwater and wrapped himself in a towel. When he left the bathroom, I gathered up my clothes and quickly got dressed. I couldn’t wait to tell my best friend back home what I had learned.

Grandpa did tell me not to mention my lesson to Grandma. He said they disagreed on when a girl should learn the important facts of life. I promised.

The train ride home felt different than the trip there. I left Barbie and Ken in their box, but now they faced each other in case they wanted to make a baby.

My mother picked me up from the train, and as soon as we got home I asked if I could go to see my best friend, Emily. She lived down the street, and since she was a late-in-life child with much older siblings, she had the best of everything, including a playroom that was just for her.

When I arrived, Emily hugged me as if I had been gone forever and we went into the playroom. We took out all the dolls and clothes and set out to create their lives in miniature.

“I know how babies are made,” I told Emily matter-of-factly.

“I do too,” she bragged. She explained the same “God planting the seed” story that we both must have heard at church, and so I decided to show her with our dolls.

“That can’t be true.” She seemed shocked.

“No, it is true. My grandpa took a bath with me and showed me how the man makes the seeds in his penis that are planted inside the woman. He said it was time for me to learn the right way.”

“Did you see his penis?” Emily asked with her eyes opened wide.

“Of course, I did, silly. How else would he have shown me how it all worked?” Emily disappeared for a few minutes, and I continued to pretend that Barbie was cooking a casserole in the Barbie kitchen. After a while Emily returned with her mother, a stylish woman who wore her hair piled up on top of her head like a movie star.

“Dianne, come join us for a snack,” she said, guiding us up to the kitchen. She had made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on Wonder Bread and added Bosco to our milk. We chewed on our sandwiches as we had many times, but Emily’s mother kept staring at me.

“Dianne, Emily told me about what happened at your grandfather’s house. You do know that grown men are not supposed to take baths with little girls and tell them about where babies come from?”

I knew it felt weird when it happened, but it was my grandpa, and if he thought it was time for me to know the truth, then it must have been time.

“Dianne, you need to tell your mother what happened at your grandpa’s house. She needs to know.”

I had not thought about telling my mom. Even though I didn’t think much of what had happened, I had a feeling that telling my mother would be embarrassing.

“If you don’t tell her, I will,” Emily’s mother insisted. I knew that she would too, because she and my mother were friends who often went to each other’s houses for coffee.