Полная версия

Finest Years: Churchill as Warlord 1940–45

At a four-hour war cabinet meeting that afternoon, following Reynaud’s departure, the merits of seeking a settlement with Hitler were discussed. Churchill hoped that France might receive terms that precluded her occupation by the Germans. Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, expressed his desire to seek Italian mediation with Hitler, to secure terms for Britain. He had held preliminary talks with Mussolini’s ambassador in London about such a course. Churchill was sceptical, saying this presupposed that a deal might be made merely by returning Germany’s old colonies, and making concessions in the Mediterranean. ‘No such option was open to us,’ said the prime minister.

Six Alexander Cadogan, who joined the meeting after half an hour, found Churchill ‘too rambling and romantic and sentimental and temperamental’. This was harsh. The prime minister bore vast burdens. It behoved him to be circumspect in all dealings with the old appeasers among his colleagues. There were those in Whitehall who, rather than being stirred by Churchill’s appeals to recognise a great historic moment, curled their lips. Chamberlain’s private secretary, Arthur Rucker, responded contemptuously to the ringing phrases in one of the prime minister’s missives: ‘He is still thinking of his books.’ Eric Seal, the only one of Churchill’s private secretaries who established no close rapport with him,* muttered about ‘blasted rhetoric’.

A substantial part of the British ruling class, MPs and peers alike, had since September 1939 lacked faith in the possibility of military victory. Although Churchill was himself an aristocrat, he was widely mistrusted by his own kind. Since the 1917 Russian Revolution, many British grandees, including such dukes as Westminster, Wellington and Buccleuch, and such lesser peers as Lord Phillimore, had shown themselves much more hostile to Soviet communism than to European fascism. Their patriotism was never in doubt. However, their enthusiasm for a fight to the finish with Hitler, which they feared would end in rubble and ruin, was less assured. Lord Hankey observed acidly before making a speech to the House of Lords early in May that he ‘would be addressing most of the members of the Fifth Column’.

Lord Tavistock, soon to become Duke of Bedford, a pacifist and plausible quisling, wrote to former prime minister David Lloyd George that Hitler’s strength was ‘so great…it is madness to suppose we can beat him by war on the continent’. On 15 May, Tavistock urged Lloyd George that peace should be made ‘now rather than later…If the Germans received fair peace terms a dozen Hitlers could never start another war on an inadequate…pretext.’ Likewise, some financial magnates in the City of London were sceptical of any possibility of British victory, and thus of Churchill. Harold Nicolson wrote: ‘It is not the descendants of the old governing classes who display the greatest enthusiasm for their leader…Mr Chamberlain is the idol of the business men…They do not have the same personal feelings for Mr Churchill…There are awful moments when they feel that Mr Churchill does not find them interesting.’

There were also defeatists lower down the social scale. Muriel Green, who worked at her family’s garage in Norfolk, recorded a conversation at a local tennis match with a grocer’s roundsman and a schoolmaster on 23 May. ‘I think they’re going to beat us, don’t you?’ said the roundsman. ‘Yes,’ said the schoolmaster. He added that as the Nazis were very keen on sport, he expected ‘we’d still be able to play tennis if they did win’. Muriel Green wrote: ‘J said Mr M. was saying we should paint a swastika under the door knocker ready. We all agreed we shouldn’t know what to do if they invade. After that we played tennis, very hard exciting play for 2 hrs, and forgot all about the war.’

In those last days of May, the prime minister must have perceived a real possibility, even a likelihood, that if he himself appeared irrationally intransigent, the old Conservative grandees would reassert themselves. Amid the collapse of all the hopes on which Britain’s military struggle against Hitler were founded, it was not fanciful to suppose that a peace party might gain control in Britain. Some historians have made much of the fact that at this war cabinet meeting Churchill failed to dismiss out of hand an approach to Mussolini. He did not flatly contradict Halifax when the Foreign Secretary said that if the Duce offered terms for a general settlement ‘which did not postulate the destruction of our independence…we should be foolish if we did not accept them’. Churchill conceded that ‘if we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies, he would jump at it’. At the following day’s war cabinet he indicated that if Hitler was prepared to offer peace in exchange for the restoration of his old colonies and the overlordship of central Europe, a negotiation could be possible.

It seems essential to consider Churchill’s words in context. First, they were made in the midst of long, weary discussions, during which he was taking elaborate pains to appear reasonable. Halifax spoke with the voice of logic. Amid shattering military defeat, even Churchill dared not offer his colleagues a vision of British victory. In those Dunkirk days, the Director of Military Intelligence told a BBC correspondent: ‘We’re finished. We’ve lost the army and we shall never have the strength to build another.’ Churchil did not challenge the view of those who assumed that the war would end, sooner or later, with a negotiated settlement rather than with a British army marching into Berlin. He pitched his case low because there was no alternative. A display of exaggerated confidence would have invited ridicule. He relied solely upon the argument that there was no more to lose by fighting on, than by throwing in the hand.

How would his colleagues, or even posterity, have assessed his judgement had he sought at those meetings to offer the prospect of

military triumph? To understand what happened in Britain in the summer of 1940, it is essential to acknowledge the logic of impending defeat. This was what created tensions between the hearts and minds even of staunch and patriotic British people. The best aspiration they, and their prime minister, could entertain was a manly determination to survive today, and to pray for a better tomorrow. The war cabinet discussions between 26 and 28 May took place while it was still doubtful that any significant portion of the BEF could be saved from France.

At the meeting of 26 May, with the support of Attlee, Greenwood and eventually Chamberlain, Churchill summed up for the view that there was nothing to be lost by fighting on, because no terms which Hitler might offer in the future were likely to be worse than those now available. Having discussed the case for a parley, he dismissed it, even if Halifax refused to do so. At 7 o’clock that evening, an hour after the war cabinet meeting ended, the Admiralty signalled the Flag Officer Dover, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay: ‘Operation Dynamo is to commence.’ The destroyers of the Royal Navy, aided by a fleet of small craft, began to evacuate the BEF from Dunkirk.

That night yet another painful order was forced upon Churchill. The small British force at Calais, drawn from the Rifle Brigade, had only nuisance value. But everything possible must be done to distract German forces from the Dunkirk perimeter. The Rifles had to resist to the last. Ismay wrote: ‘The decision affected us all very deeply, especially perhaps Churchill. He was unusually silent during dinner that evening, and ate and drank with evident distaste.’ He asked a private secretary, John Martin, to find for him a passage in George Borrow’s 1843 prayer for England. Martin identified the lines next day: ‘Fear not the result, for either thy end be a majestic and an enviable one, or God shall perpetuate thy reign upon the waters.’

On the morning of the 27th, even as British troops were beginning to embark at Dunkirk, Churchill asked the leaders of the armed forces to prepare a memorandum setting out the nation’s prospects of resisting invasion if France fell. Within a couple of hours the chiefs of staff submitted an eleven-paragraph response that identified the key issues with notable insight. As long as the RAF was ‘in being’, they wrote, its aircraft together with the warships of the Royal Navy should be able to prevent an invasion. If air superiority was lost, however, the navy could not indefinitely hold the Channel. Should the Germans secure a beachhead in south-east England, British home forces would be incapable of evicting them. The chiefs pinpointed the air battle, Britain’s ability to defend its key installations, and especially aircraft factories, as the decisive factors in determining the future course of the war. They concluded with heartening words: ‘The real test is whether the morale of our fighting personnel and civil population will counter-balance the numerical and material advantages which Germany enjoys. We believe it will.’

The war cabinet debated at length, and finally accepted, the chiefs’ report. It was agreed that further efforts should be made to induce the Americans to provide substantial aid. An important message arrived from Lord Lothian, British ambassador in Washington, suggesting that Britain should invite the US to lease basing facilities in Trinidad, Newfoundland and Bermuda. Churchill opposed any such unilateral offer. America had ‘given us practically no help in the war’, he said. ‘Now that they saw how great was the danger, their attitude was that they wanted to keep everything that would help us for their own defence.’ This would remain the case until the end of the battle for France. There was no doubt of Roosevelt’s desire to help, but he was constrained by the terms of the Neutrality Act imposed by Congress. On 17 May Gen. George Marshall, chief of the army, expounded to US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau his objections to shipping American arms to the Allies: ‘It is a drop in the bucket on the other side and it is a very vital necessity on this side and that is that. Tragic as it is, that is it.’ Between 23 May and 3 June US Secretary of War Harry Woodring, an ardent isolationist, deliberately delayed shipment to Britain of war material condemned as surplus. He insisted that there must be prior public advertisement before such equipment was sold to the Allies. On 5 June, the Senate foreign relations committee rejected an administration proposal to sell ships and planes to Britain. The US War Department declined to supply bombs to fit dive-bombers which the French had already bought and paid for.

In the last days of May, a deal for Britain to purchase twenty US patrol torpedo boats was scuttled when news of it leaked to isolationist Senator David Walsh of Massachusetts. As chairman of the Senate’s Navy Affairs Committee, Walsh referred the plan to the attorney-general—who declared it illegal. In mid-June, the US chiefs of staff recommended that no further war material should be sent to Britain, and that no private contractor should be allowed to accept an order which might compromise the needs of the US armed forces. None of this directly influenced the campaign in France. But it spoke volumes, all unwelcome in London and Paris, about the prevailing American mood towards Europe’s war.

It was a small consolation that other powerful voices across the Atlantic were urging Britain’s cause. The New York Times attacked Colonel Charles Lindbergh, America’s arch-isolationist flying hero, and asserted the mutuality of Anglo-American interests. Lindbergh, said the Times, was ‘an ignorant young man if he trusts his own premise that it makes no difference to us whether we are deprived of the historic defense of British sea power in the Atlantic Ocean’. The Republican New York Herald Tribune astonished many Americans by declaring boldly: ‘The least costly solution in both life and welfare would be to declare war on Germany at once.’ Yet even if President Roosevelt had wished to heed the urgings of such interventionists and offer assistance to the Allies, he had before him the example of Woodrow Wilson, in whose administration he served. Wilson was renounced by his own legislature in 1919 for making commitments abroad—in the Versailles Treaty—which outreached the will of the American people. Roosevelt had no intention of emulating him.

Chamberlain reported on 27 May that he had spoken the previous evening to Stanley Bruce, Australian high commissioner in London, who argued that Britain’s position would be bleak if France surrendered. Bruce, a shrewd and respected spokesman for his dominion, urged seeking American or Italian mediation with Hitler. Australia’s prime minister, Robert Menzies, was fortunately made of sterner stuff. From Canberra, Menzies merely enquired what assistance his country’s troops could provide. By autumn, three Australian divisions were deployed in the Middle East. Churchill told Chamberlain to make plain to Bruce that France’s surrender would not influence Britain’s determination to fight on. He urged ministers—and emphasised the message in writing a few days later—to present bold faces to the world. Likewise, a little later he instructed Britain’s missions abroad to entertain lavishly, prompting embassy parties in Madrid and Berne. In Churchill’s house, even amid disaster there was no place for glum countenances.

At a further war cabinet that afternoon, Halifax found himself unsupported when he returned to his theme of the previous day, seeking agreement that Britain should solicit Mussolini’s help in exploring terms from Hitler. Churchill said that at that moment, British prestige in Europe was very low. It could be revived only by defiance. ‘If, after two or three months, we could show that we were still unbeaten, we should be no worse off than we should be if we were now to abandon the struggle. Let us therefore avoid being dragged down the slippery slope with France.’ If terms were offered, he would be prepared to consider them. But if the British were invited to send a delegate to Paris to join with the French in suing for peace with Germany, the answer must be ‘no’. The war cabinet agreed.

Halifax wrote in his diary: ‘I thought Winston talked the most frightful rot. I said exactly what I thought of [the Foreign Secretary’s opponents in the war cabinet], adding that if that was really their view, our ways must part.’ In the garden afterwards, when he repeated his threat of resignation, Churchill soothed him with soft words. Halifax concluded in his diary record: ‘It does drive one to despair when he works himself up into a passion of emotion when he ought to make his brain think and reason.’ He and Chamberlain recoiled from Churchill’s ‘theatricality’, as Cadogan described it. Cold men both, they failed to perceive in such circumstances the necessity for at least a semblance of boldness. But Chamberlain’s eventual support for Churchill’s stance was critically important in deflecting the Foreign Secretary’s proposals.

Whichever narratives of these exchanges are consulted, the facts seem plain. Halifax believed that Britain should explore terms. Churchill must have been deeply alarmed by the prospect of the Foreign Secretary, the man whom only three weeks earlier most of the Conservative Party wanted as prime minister, quitting his government. It was vital, at this moment of supreme crisis, that Britain should present a united face to the world. Churchill could never thereafter have had private confidence in Halifax. He continued to endure him as a colleague, however, because he needed to sustain the support of the Tories. It was a measure of Churchill’s apprehension about the resolve of Britain’s ruling class that it would be another seven months before he felt strong enough to consign ‘the Holy Fox’ to exile.

The legend of Britain in the summer of 1940 as a nation united in defiance of Hitler is rooted in reality. It is not diminished by asserting that if another man had been prime minister, the political faction resigned to seeking a negotiated peace would probably have prevailed. What Churchill grasped, and Halifax and others did not, was that the mere gesture of exploring peace terms must impact disastrously upon Britain’s position. Even if Hitler’s response proved unacceptable to a British government, the clear, simple Churchillian posture, of rejecting any parley with the forces of evil, would be irretrievably compromised.

It is impossible to declare with confidence at what moment during the summer of 1940 Churchill’s grip upon power, as well as his hold upon the loyalties of the British people, became secure. What is plain is that in the last days of May he did not perceive himself proof against domestic foes. He survived in office not because he overcame the private doubts of ministerial and military sceptics, which he did not, but by the face of courage and defiance that he presented to the nation. He appealed over the heads of those who knew too much, to those who were willing to sustain a visceral stubbornness. ‘His world is built upon the primacy of public over private relationships,’ wrote the philosopher Isaiah Berlin in a fine essay on Churchill, ‘upon the supreme value of action, of the battle between simple good and simple evil, between life and death; but above all battle. He has always fought.’ The simplicity of Churchill’s commitment, matched by the grandeur of the language in which he expressed this, seized popular imagination. In the press, in the pubs and everywhere that Churchill himself appeared on his travels across the country, the British people passionately applauded his defiance. Conservative seekers after truce were left beached and isolated; sullenly resentful, but impotent.

Evelyn Waugh’s fictional Halberdier officer, the fastidious Guy Crouchback, was among many members of the British upper classes who were slow to abandon their disdain for the prime minister, displaying an attitude common among real-life counterparts such as Waugh himself:

Some of Mr Churchill’s broadcasts had been played on the mess wireless-set. Guy had found them painfully boastful and they had, most of them, been immediately followed by the news of some disaster…Guy knew of Mr Churchill only as a professional politician, a master of sham-Augustan prose, an advocate of the Popular Front in Europe, an associate of the press-lords and Lloyd George. He was asked: ‘Uncle, what sort of fellow is this Winston Churchill?’ ‘Like Hore-Belisha [sacked Secretary for War, widely considered a charlatan], except that for some reason his hats are thought to be funny’…Here Major Erskine leant across the table. ‘Churchill is about the only man who may save us from losing this war,’ he said. It was the first time that Guy had heard a Halberdier suggest that any result, other than complete victory, was possible.

Some years before the war, the diplomat Lord D’Abernon observed with patrician complacency that ‘An Englishman’s mind works best when it is almost too late.’ In May 1940, he might have perceived Churchill as an exemplar of his words.

* Seal departed from Downing Street in 1941.

TWO The Two Dunkirks

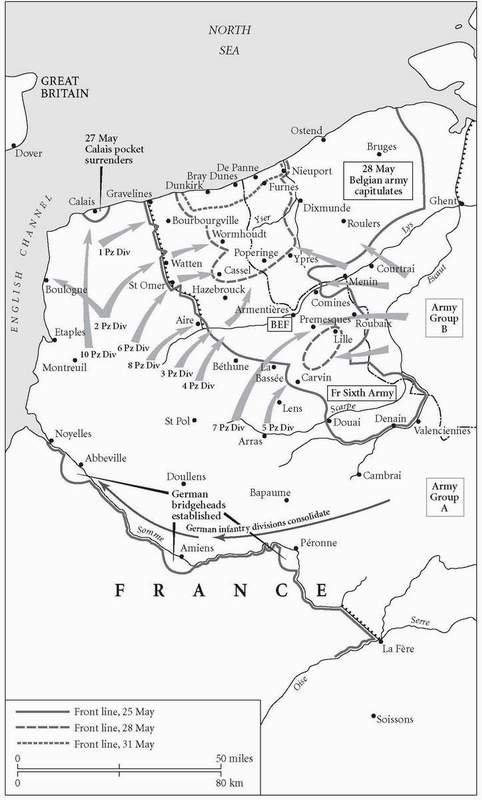

On 28 May, Churchill learned that the Belgians had surrendered at dawn. He repressed until much later his private bitterness, unjustified though this was when Belgium had no rational prospect of sustaining the fight. He merely observed that it was not for him to pass judgement upon King Leopold’s decision. Overnight a few thousand British troops had been retrieved from Dunkirk, but Gort was pessimistic about the fate of more than 200,000 who remained, in the face of overwhelming German air power. ‘And so here we are back on the shores of France on which we landed with such high hearts over eight months ago,’ Pownall, Gort’s chief of staff, wrote that day. ‘I think we were a gallant band who little deserve this ignominious end to our efforts…If our skill be not so great, our courage and endurance are certainly greater than that of the Germans.’ The stab of self-knowledge reflected in Pownall’s phrase about the inferior professionalism of the British Army lingered in the hearts of its intelligent soldiers until 1945.

That afternoon at a war cabinet meeting in Churchill’s room at the Commons, the prime minister again—and for the last time—rejected Halifax’s urgings that the government could obtain better peace terms before France surrendered and British aircraft factories were destroyed. Chamberlain, as ever a waverer, now supported the Foreign Secretary in urging that Britain should consider ‘decent terms if such were offered to us’. Churchill said that the odds were a thousand to one against any such Hitlerian generosity, and warned that ‘nations which went down fighting rose again, but those which surrendered tamely were finished’. Attlee and Greenwood, the Labour members, endorsed Churchill’s view. This was the last stand of the old appeasers. Privately, they adhered to the view, shared by former prime minister Lloyd George, that sooner or later negotiation with Germany would be essential. As late as 17 June, the Swedish ambassador reported Halifax and his junior minister R.A. Butler declaring that no ‘diehards’ would be allowed to stand in the way of peace ‘on reasonable conditions’. Andrew Roberts has convincingly argued that Halifax was not directly complicit in remarks made during a chance conversation between Butler and the envoy. But it remains extraordinary that some historians have sought to qualify verdicts on the Foreign Secretary’s behaviour through the summer of 1940. It was not dishonourable – the lofty eminence could never have been that. But it was craven.

Immediately following the 28 May meeting, some twenty-five other ministers – all those who were not members of the war cabinet – filed into the room to be briefed by the prime minister. He described the situation at Dunkirk, anticipated the French collapse, and expressed his conviction that Britain must fight on. ‘He was quite magnificent,’ wrote Hugh Dalton, Minister of Economic Warfare, ‘the man, and the only man we have, for this hour…He was determined to prepare public opinion for bad tidings…Attempts to invade us would no doubt be made.’ Churchill told ministers that he had considered the case for negotiating with ‘that man’ – and rejected it. Britain’s position, with its fleet and air force, remained strong. He concluded with a magnificent peroration: ‘I am convinced that every man of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.’

He was greeted with acclamation extraordinary at any assembly of ministers. No word of dissent was uttered. The meeting represented an absolute personal triumph. He reported its outcome to the war cabinet. That night, the British government informed Reynaud in Paris of its refusal of Italian mediation for peace terms. A further suggestion by Halifax of a direct call upon the United States was dismissed. A bold stand against Germany, Churchill reiterated, would carry vastly more weight than ‘a grovelling appeal’ at such a moment. At the following day’s war cabinet, new instructions to Gort were discussed. Halifax favoured giving the C-in-C discretion to capitulate. Churchill would hear of no such thing. Gort was told to fight on at least until further evacuation from Dunkirk became impossible. Mindful of Allied reproaches, he told the War Office that French troops in the perimeter must be allowed access to British ships. He informed Reynaud of his determination to create a new British Expeditionary Force, based on the Atlantic port of Saint-Nazaire, to fight alongside the French army in the west.

All through those days, the evacuation from the port and beaches continued, much hampered by lack of small craft to ferry troops out to the larger ships, a deficiency which the Admiralty strove to make good by a public appeal for suitable vessels. History has invested the saga of Dunkirk with a dignity less conspicuous to those present. John Horsfall, a company commander of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, told a young fellow officer: ‘I hope you realise your distinction. You are now taking part in the greatest military shambles ever achieved by the British Army.’ Many rank-and-file soldiers returned from France nursing a lasting resentment towards the military hierarchy that had exposed them to such a predicament. Horsfall noticed that in the last phase of the march to the beaches, his men fell unnaturally silent: ‘There was a limit to what any of us could absorb, with those red fireballs flaming skywards every few minutes, and I suppose we just reached the point where there was little left to say.’ They were joined by a horse artillery major, superb in Savile Row riding breeches and scarlet and gold forage cap, who said: ‘I’m a double blue at this, old boy – I was at Mons [in 1914].’ A young Grenadier Guards officer, Edward Ford, passed the long hours of waiting for a ship reading a copy of Chapman’s Homer which he found in the sands. For the rest of his days, Ford was nagged by unsatisfied curiosity about who had abandoned his Chapman amid the detritus of the beaches.