Полная версия

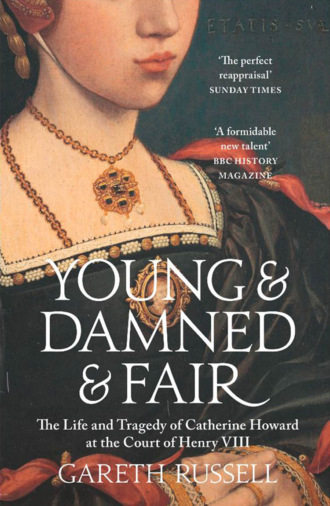

Young and Damned and Fair: The Life and Tragedy of Catherine Howard at the Court of Henry VIII

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Gareth Russell 2017

Maps and family trees by Martin Brown

Extract from Die Lorelei from Collected Poems and Drawings by Stevie Smith, London, Faber and Faber Ltd, 2015. Kind permission granted by the publishers.

Cover image shows ‘Portrait of a Young Woman, 1540–45, oil on wood’, Holbein, Hans the Younger (1497–1543). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 (49.7.30) © 2016 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Gareth Russell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008128289

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008128296

Version: 2017-12-06

DEDICATION

For my grandparents,

Robert and Mary Russell

and

Richard and Iris Mahaffy

EPIGRAPH

An antique story comes to me

And fills me with anxiety,

I wonder why I fear so much

What surely has no modern touch?

… There, on a rock majestical,

A girl with smile equivocal

Painted, young and damned and fair

Sits and combs her yellow hair.

– Stevie Smith, Die Lorelei

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

Family Trees

Introduction

1. The Hour of Our Death

2. Our Fathers in Their Generation

3. Lord Edmund’s Daughter

4. The Howards of Horsham

5. Mad Wenches

6. The King’s Highness Did Cast a Fantasy

7. The Charms of Catherine Howard

8. The Queen of Britain Will Not Forget

9. All These Ladies and My Whole Kingdom

10. The Queen’s Brothers

11. The Return of Francis Dereham

12. Jewels

13. Lent

14. For They Will Look Upon You

15. The Errands of Morris and Webb

16. The Girl in the Silver Dress

17. The Chase

18. Waiting for the King of Scots

19. Being Examined by My Lord of Canterbury

20. A Greater Abomination

21. The King Has Changed His Love into Hatred

22. Ars Moriendi

23. The Shade of Persephone

Appendix I: The Alleged Portraits of Catherine Howard

Appendix II: The Ladies of Catherine Howard’s Household

Appendix III: The Fall of Catherine Howard

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Picture Section

Bibliography

Notes

Index

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

In the Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace, magnificent tapestries depicting scenes from the life of the patriarch Abraham are on display. Every day, hundreds of tourists pass these enormous works of art which cost Henry VIII almost as much as the construction of a new warship. After centuries of exposure, their colours had faded and the bright sparkle of the threads of beaten gold had worn away, until a lengthy conservation project carried out between the Historic Royal Palaces, the Clothworkers’ Company, and the University of Manchester offered a reconstruction and an academic paper conveying just how vibrant the tapestries would have been when they were first unveiled. Their detail is extraordinary, mesmeric. The reflections of mallard ducks floating on the ponds are visible, reeds sway in the wind, every face is detailed, sandals and toenails are stitched perfectly, bread in a servant’s basket is believably coloured. Crucially, part of the conservation work necessitated turning the tapestries over to look at the threads at the back and see all the ugly, confusing stitch-work that had gone into making the familiar scene on the front possible.

My interest in the story of Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Queen Catherine Howard, began years ago and solidified in 2011 when, under the supervision of Dr James Davis at Queen’s University, Belfast, I completed my postgraduate dissertation on her household.1 As with all Henry’s wives, Catherine’s life had been written about many times in biographies and studies of her husband’s reign. In the year of Henry VIII’s death, an Italian merchant remarked, ‘The discourse of these wives is a wonderful history’, an observation that captures why the Tudors remain one of England’s most famous dynasties.2 In Catherine’s case, the circumstances of her career had already been dissected in A Tudor Tragedy: The Life and Times of Catherine Howard, first published in New York in 1961 and generally judged the standard biography of her. Written by Professor Lacey Baldwin Smith, the central contention of A Tudor Tragedy was that Catherine’s ‘career begins and ends with the Howards, a clan whose predatory instincts for self-aggrandisement, sense of pompous conceit, and dangerous meddling in the destinies of state, shaped the course of her tragedy.’3

I intended to use Catherine’s sixteen-month period as queen consort as a useful framing device to analyse the queen’s household, one of the least-studied but most fascinating components of Henry VIII’s court: how it functioned, who populated it, who dominated it, how it was financed, and how it interacted with the wider court.4 The thesis would place one early modern queen of England, in this case the hapless Catherine Howard, in the context of a life lived not just next to the great men of the early English Reformation but amongst the servants, ladies-in-waiting, and favourites, without whom no great aristocratic lady could function and from whom she was seldom, if ever, separated. I did not, initially, expect to find anything remarkably different about her rise and fall.

Instead, I came to the conclusion that the queen’s household had shaped the trajectory of Catherine’s career. Popular culture often presents Tudor royal households, particularly a queen’s, as beautiful irrelevances. Sumptuously dressed ladies-in-waiting whispering behind their fans, dancing or throwing coy glances, are familiar images of life in the queens’ establishments. In many works of fiction, these characters seem to spend a good deal of their time giggling over something which is not credibly amusing. The reality was far more interesting.

Establishing who Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting were was a difficult task. The surviving list, which was for a long time incorrectly believed to be a list of women attached to the household of Catherine’s predecessor, Anne of Cleves, gives the women by their title or surname, and for a few of the figures I had to undertake some guesswork based on Tudor women with the right background, name, and family ties to court. It was, however, possible to prove that several candidates who are usually identified as her ladies-in-waiting were never in Catherine’s service – the 9th Earl of Kildare’s daughter, Lady Elizabeth Fitzgerald, was not one of her maids of honour and the ‘Lady Howard’ mentioned was neither Catherine’s stepmother nor one of her sisters, but her aunt by marriage, Lady Margaret Howard (née Gamage). Neither was the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk or the Countess of Bridgewater asked to join the household, despite their closeness to the queen. The more I researched, the more convinced I became that the influence and intentions of Catherine’s family had been exaggerated or, at least, misrepresented, and acting on the advice of a professor, I began to consider a full-length study of Catherine’s horribly compelling story.

The result, this book, is as much a study of Catherine Howard’s world as it is a study of her personal life. Some biographies have a tendency to inflate and isolate their subjects, by endowing them with more importance or independence from the world around them than they actually possessed. The impact of religious changes, international diplomacy, and court etiquette will all be discussed in depth, not just because they are fascinating topics in their own right, but because directly or indirectly they shaped Catherine’s story. Like the Hampton Court tapestries, it is the details of the background figures and the threads weaving behind them which together produced the image.

Putting her household, and her grandmother’s, at the centre of a biography of Catherine makes her story a grand tale of the Henrician court in its twilight, a glittering but pernicious sunset, in which the king’s unstable behaviour and his courtiers’ labyrinthine deceptions ensured that fortune’s wheel was moving more rapidly than at any previous point in his vicious but fascinating reign. Accounts of the gorgeous ceremonies held to celebrate the resubmission of the north to royal control saw Catherine, the girl in the silver dress, gleaming, Daisy Buchanan-like, safe and proud above the hot struggles of the poor – the perfect medieval royal consort. Until, like a bolt out of the heavens, a scandal resulted in an investigation in which nearly everyone close to Catherine was questioned and which ultimately wrapped itself in ever more intricate coils around the young queen until, to her utter bewilderment, it choked life from her entirely.

The downfall of Catherine Howard took place from 2 November 1541 to 13 February 1542. To narrate and analyse what happened, I have relied on four or five different types of documents. There are the official proclamations and correspondence from Henry’s government, principally but not exclusively orders issued by the Privy Council which help establish the broad chronology of Catherine’s fall and the Crown’s eventual version of events. There are numerous surviving if incomplete transcripts of interrogations held between the first week of November and third week of December 1541, to which we might add the subcategory of the queen’s own confessions, framed as letters to her husband. The diplomatic correspondence of the Hapsburg, French, and Clevian ambassadors are invaluable, not least because, while they were initially confused about what was happening, they ultimately left the fullest accounts of events as they unfolded to an outsider’s gaze, particularly Charles de Marillac and Eustace Chapuys. Lastly, there are a few surviving letters or chronicles that give clues to the English public’s reaction to the affair.

Interpretation of this evidence is fraught with difficulty. Many supporting or referenced documents did not survive the Cotton Library fire of 1731 and some that did were badly damaged by the smoke.5 That many interviews with those who served either Catherine or her family were conducted but have not survived to the present is proved by the councillors’ notes, where they jotted down their intention to summon a witness for a second or third round of questioning, the transcripts of which have since been lost. We know, for instance, that Catherine was rash enough to send Morris, one of her pageboys, to the rooms of her alleged lover Thomas Culpepper with food for Culpepper when he was ill. Yet if young Morris was questioned about what he had brought to Culpepper’s rooms, as seems probable, then the transcripts of his interrogation do not survive. Nor do those of Catherine’s former secretary Joan Bulmer, who must have been questioned given the fact that she was subsequently incarcerated for her actions. The queen’s fleeting mention of Morris’s involvement in bringing gifts to Culpepper, usually overlooked, reminds us that numerous members of the household must have been aware, or at the very least suspicious, of the queen’s actions and that much of the evidence concerning her behaviour most likely came from sources other than the principals.

The extant records of the interrogations were written quickly, as the deponent gave his or her testimony, and so translating the increasingly illegible scrawl or deciphering the mounting number of abbreviations present their own challenges.6 Many of these transcripts were translated in full for the first time by David Starkey for his book Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003). Anyone studying Catherine Howard’s life is indebted to Dr Starkey for that, particularly his work on Thomas Culpepper’s testimony and Henry Manox’s. I wonder if I might have suffered deeply from doubt at my translations of some of Manox’s biological vocabulary had I not already known that ‘the worst word in the language’ had been spotted by another.

Separate to the illegible and the vanished, there is of course the question of intent. A common supposition about Catherine’s downfall is that the people who were quizzed lied, because their interrogators or their own panic pressured them into doing so. At least two of the main witnesses were tortured later in the interrogation and one of them almost certainly faced similar horrors earlier. Another witness gave a piece of evidence damning Catherine that can neither be refuted nor verified. It is up to the reader to interpret it as an honest mistake, an accurate testimony, or a lie born of malice or fear.

Yet, even with all these shortcomings, acknowledged and grappled with, there is enough for us to piece together the various stages of the process of Catherine’s downfall and its dominant characteristics. Scraps of achingly intimate detail survive – we know that the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk held a candle as she stood over a broken-into chest and the colour of the dress Catherine wore for her final journey by river. Beyond reasonable doubt, what happened in 1541 was not a coup launched with the intention of destroying the queen or her family. Some, if not many, of those involved may have been delighted to embarrass or undermine the Howards, but it was never the primary motivating factor. The government was responding to an unprecedented and unexpected set of developments. In the scrawl of ink on singed or water-damaged pages, amid lists upon lists of questions and the panicked, scratched-out signatures of frightened servants, there is nothing to suggest that Henry VIII’s advisers were doing anything other than pursuing the evidence in front of them. Some of their conclusions may have been wrong, but they were not incomprehensible or unreasonable. When torture was used, it did not produce any evidence to contradict the testimonies of those whose bodies had not been brutalised. The fact that Queen Catherine shared a set of grandparents, a husband, and a similar finale with Anne Boleyn has produced a misleading impression that the two queens’ fates were broadly similar. To compare them in detail is to produce a study in contrast. The circumstances of Anne Boleyn’s downfall are notorious, and the weight of modern academic opinion supports the scepticism of many of her contemporaries about her guilt. Anne’s queenship collapsed over seventeen days in May 1536, the evidence against her was given by the only deponent from a background humble enough to allow torture and, as Sir Edward Baynton wrote, in the queen’s household in May 1536 there was ‘much communication that no man will confess any thing against her’.7

The implosion of Catherine’s marriage was a very different affair. Three months were taken to determine her fate, Parliament was consulted, embassies were invited to send representatives to the trials of the queen’s co-accused, witnesses were fetched back for multiple rounds of questions, and a thorough agenda was set for each interrogation. So the interpretation of Anne Boleyn’s downfall as one in which a powerful but divisive queen consort was harried to her death with maximum speed, minimum honesty, and determined hatred has no bearing on her cousin’s fate five years later. What happened to Catherine Howard was monstrous and it struck many of her contemporaries as unnecessary, but it was not a lynching. The queen was toppled by a combination of bad luck, poor decisions, and the Henrician state’s determination to punish those who failed its king. A modern study of Henry’s marriages offered the conclusion that if ‘ever a butterfly was broken on the wheel, it must surely have been Catherine Howard’, and in the sense that the wheel in question was her husband’s government, there was an inexorable quality about the way it turned to crush Catherine after 2 November 1541.8

I have spelled Catherine’s name with a ‘C’ to differentiate her from other Katherines in a generation with many. Her name has been given as Katherine, Katharine, Catharine, and Kathryn in other biographies, and standardised spelling was never a sixteenth-century priority. For clarity’s sake, Catherine’s two stepdaughters are usually referred to here as princesses. Each sister had been styled as a princess from the time of her birth until the annulment of her mother’s marriage, after which they were both addressed by the honorific of ‘lady’, even when they were rehabilitated into the line of succession. During their brother’s reign, they were interchangeably referred to by both titles, owing to their positions as first and second in line to the throne, and Elizabeth was often referred to as Princess Elizabeth during Mary’s time as queen. To mark them out from the other Marys and Elizabeths, I have decided to err on the side of politesse in giving both women the higher title when they are mentioned in passing. For similar reasons, I have sometimes given the names of foreign princesses in their native language – hence Maria of Austria and Marie de Guise, rather than the anglicised Mary. Where possible, I have tried to be consistent – Maria of Austria was also known as Mary of Hungary, Catherine’s sister Isabella is Isabel in some sources. Likewise, the surnames of many of those involved in Catherine’s story vary – Culpepper is Culpeper; Dereham is given as Durham, Durant, or Deresham; Edgcumbe or Edgecombe; Habsburg or Hapsburg; Knyvet or Knyvett; Mannox, Manox or Mannock; Damport or Davenport. Where required, I have chosen a common spelling.

I have modernised the spelling in quotations from the original documents. All quotations from the Bible are taken either from the Douay-Rheims or King James editions. I have avoided giving estimations of modern equivalents to Tudor money, since they are often misleading and, at best, imprecise. Prior to 1752, England operated under the Julian calendar, and the new calendar year commenced on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation, rather than on 1 January. By our reckoning, Catherine Howard was executed on 13 February 1542, but her contemporaries in England would have given 1541 as the year of her death. Almost all historians give the modern dating and I have followed suit.

Chapter 1

The Hour of Our Death

Renounce the thought of greatness, tread on fate,

Sigh out a lamentable tale of things

Done long ago, and ill done; and when sighs

Are wearied, piece up what remains behind

With weeping eyes, and hearts that bleed to death.

– John Ford, The Lover’s Melancholy (1628)

A benefit of being executed was that one avoided any chance of the dreaded mors improvisa, a sudden death by which a Christian soul might be denied the opportunity to make their peace. So when Thomas Cromwell was led out to his death on 28 July 1540, he had the comfort of knowing that he had been granted the privilege of preparing to stand in the presence of the Almighty. The day was sweltering, one in a summer so hot and so dry that no rain fell on the kingdom from spring until the end of September, but the bulky hard-bitten man from Putney who had become the king’s most trusted confidant and then his chief minister1 walked cheerfully towards the scaffold.2 He even called out to members of the crowd and comforted his nervous fellow prisoner Walter, Lord Hungerford, whose sanity was questionable, and who had been condemned to die alongside him for four crimes, all of which carried the death penalty. Firstly, he had allegedly committed heresy, in appointing as his private chaplain a priest rumoured to remain loyal to the pope. Secondly, he was accused of witchcraft, by consorting with various individuals, including one named ‘Mother Roche’, to use necromancy to guess the date of the king’s death. Treason was alleged through the appointment of his chaplain and his meeting with the witch, which constituted a crime against the king’s majesty. He was also found guilty of sodomy, ‘the abominable and detestable vice and sin of buggery’, made a capital crime in 1534, in going to bed with two of his male servants, men called William Master and Thomas Smith.3

Rumours, fermenting in the baking heat and passed between courtiers, servants, merchants and diplomats who had nothing to do but sweat and trade in secrets, had already enlarged the scope of Lord Hungerford’s crimes. The French ambassador reported back to Paris that the condemned man had also been guilty of sexually assaulting his own daughter. It was whispered that Hungerford had practised black magic, violating the laws of Holy Church that prohibited sorcery as a link to the Devil. Others heard that Hungerford’s true crime had been actively plotting the murder of the king.4 None of those charges were ever mentioned in the indictments levelled against Hungerford at his trial, but the man dying alongside him had perfected this tactic of smearing a victim with a confusing mélange of moral turpitudes guaranteed to excite prurient speculation and kill a person’s reputation before anyone was tempted to raise a voice in their defence.