Полная версия

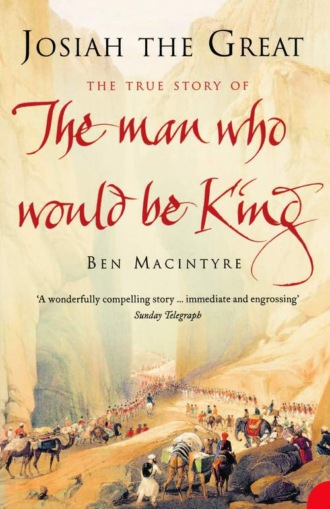

Josiah the Great: The True Story of The Man Who Would Be King

Harlan’s ideas of empire were still in their infancy when he left the roasting Indian plains and made his way to Simla, in the foothills of the Himalayas, where British officialdom was on retreat from the summer heat. Technically, as a civilian, he was now persona non grata, since neither British subjects nor foreigners were allowed to live in the interior of India without a licence, but following an interview with the Governor General Lord Amherst himself, the permit was granted. Harlan chose not to linger in the hill station. Instead, armed with his copy of Elphinstone, he headed towards Ludhiana, the Company’s last garrison town in north-west India.

Ludhiana marked the westernmost edge of British control, a dusty border post where civilisation, as the British saw it, ended, and the wilderness began. Beyond was the mysterious Punjab, and even further west, across the mighty Indus, lay mythical Afghanistan: a ‘terra incognita’, in Harlan’s words. In Simla Harlan he had learned that Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the mighty independent ruler of the Punjab, had already employed a handful of European officers to train his army in modern military techniques, and might be looking for more such recruits. The Sikh king was also famously obsessed with his health, and after barely a year as an army medical officer Harlan considered himself amply qualified to work for the maharajah as either doctor or soldier, or both.

On a late summer’s evening in 1826, accompanied by Dash and a handful of servants, Harlan rode into Ludhiana, caked in dust but still resplendent in his full service uniform complete with cocked hat. Presiding over this outpost of empire was one Captain Claude Martine Wade, the East India Company’s political agent and leader of its tiny colony of Europeans. Wade’s tasks were to police the border, maintain relations with the local Indian princes, and report back to Calcutta with whatever intelligence he could glean on the chaotic political situation beyond the frontier. He was the shrewdest of Company men, as dry and penetrating as the wind that blew off the western desert, and he observed the arrival of this unlikely young American with a mixture of interest and deep suspicion. Harlan made his way directly to Wade’s residence, and handed the British agent a document, signed by the Governor General himself, giving him permission to cross the Sutlej, the river separating the Company’s domain from that of Ranjit Singh.

Cordial but reserved, Wade invited Harlan to lodge at the residence while he made preparations for his journey. The offer was readily accepted, and having despatched a letter to Ranjit Singh by native courier requesting permission to enter the Punjab, Harlan settled down to await a reply in comfort. ‘I enjoyed the amenities of Captain W.’s hospitality,’ he wrote, noting that the Englishman ‘with the characteristic liberality of his country, extended the freedom of his mansion to all’. Over dinner, Wade explained that he maintained ‘respectful and obedient subservience from the numerous princely chieftains subject to his surveillance’ by playing one off against another. The English agent handled his delegated authority with ruthless skill, caring little what the local rulers did, to their subjects or to each other, as long as British prestige was maintained. As Kipling wrote in ‘The Man who Would be King’: ‘Nobody cares a straw for the internal administration of Native States … They are the dark places of the earth, full of unimaginable cruelty.’

Harlan was impressed by Wade’s cynical attitude to power, declaring him an ‘expert diplomatist’ and ‘a master of finesse who wielded an expedient and peculiar policy with success’. Wade in turn was intrigued by his energetic and enigmatic guest, who seemed to have plenty of money and who spoke in the most educated fashion about the local flora and classical history. Many strange types blew through Ludhiana, including the occasional European adventurer, but a mercenary-botanist-classicist was a new species altogether. Puzzled, Wade reported to Calcutta: ‘Dr Harlan’s principal object in wishing to visit the Punjab was in the first place to enter Ranjit Singh’s service and ultimately to pursue some investigation regarding the natural history of that country.’ He warned Harlan that the Company could not approve of the first part of his plan, since ‘the resort of foreigners to native courts is viewed with marked disapprobation or admitted only under a rigid surveillance’. Yet he did not try to dissuade him from heading west. In the unlikely event he survived, a man like Harlan might prove very useful in Lahore, Ranjit’s capital.

Harlan’s future was clear, at least in his own mind: he would join the maharajah’s entourage and rise to fame and fortune, while compiling a full inventory of the plants and flowers of the exotic Punjab. Like Lewis and Clark, with American bravado and learning he would open up a new world. The only hitch was that Ranjit Singh would not let him in. Although he had signed a treaty with the British back in 1809, as the greatest independent ruler left in India the maharajah was pathologically (and understandably) suspicious of feringhees, as white foreigners were called. The British were happy to let the Sikh potentate get on with building his own empire beyond the Sutlej. ‘Very little communication had heretofore existed betwixt the two governments,’ wrote Harlan. ‘The interior of the Punjab was only seen through a mysterious veil, and a dark gloom hung over and shrouded the court of Lahore.’ Which was exactly the way Ranjit Singh wanted it.

As he kicked his heels waiting for a passport that never arrived, Harlan began to form an altogether more extravagant plan that would take him far beyond the Punjab in the service of a different king, who also happened to be his neighbour in Ludhiana.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.