Полная версия

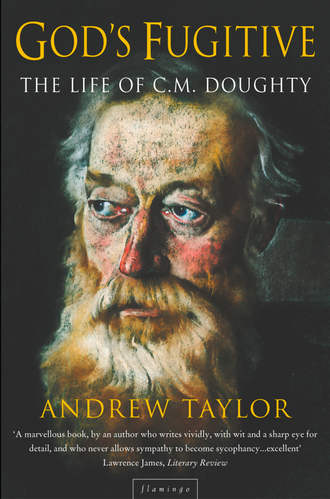

God’s Fugitive

Neither Frederick Doughty nor his wife was going to waste much time or affection on their new charge. Within months of his father’s death young Charles was packed off to school at Laleham, on the Thames, to come home only for those parts of the holidays for which they could not find another willing relative or friend to take on the burden of his keep.

For Doughty’s new guardian was going through his own financial problems, and for much the same reasons that his dead brother had done. He had been pouring money into the rebuilding of Martlesham Hall for nearly ten years when his nephew arrived – perhaps the two brothers were competing in the splendour of their ambitions. If so, they paid a heavy price: only death prevented Charles from crippling himself and his two small sons with debt, while Frederick was eventually forced to sell the Hall which was his pride and joy. ‘It was a terrible wrench to all his feelings: the building of the Hall in the Elizabethan style had been the pleasure and the hobby of his life. For years after the sale, the place was never named, or mention made of it,’ Frederick’s son dutifully recorded. By the time Martlesham was sold, Charles Doughty would have been some ten years old – old enough to sense and recognize the fresh misery that the family was going through. Perhaps there is even a hint in his cousin’s journal that the young Charles might have been made to feel some responsibility for the disaster, despite the fact that his father’s will had carefully provided for his upkeep and maintenance.

The sale of the Hall and the estate around it I fancy became inevitable in spite of a hard struggle on the part of my father to make ends meet. The growing up of children and the increasing expense of education in addition to the above sealed its fate … The sale was, I have heard on all sides, a terrible blow to my father.

Laleham, with swimming in the river Thames and cricket in a nearby meadow, seemed initially to be an ideal choice of school for a boy who was used to life in the country, and who was already, not surprisingly, showing signs of being shy and withdrawn. The Revd John Buckland had made his career as headmaster there – he had come to Laleham thirty years before with Dr Thomas Arnold, and the two young schoolmasters had set up their own establishments, Arnold preparing older boys for university, and Buckland building up one of the country’s first preparatory schools.

Arnold, of course, had moved on to greater things at Rugby School after ten years, but Buckland stayed behind. By the time he retired, three years after Charles Doughty arrived, The Times commented that he was running ‘a large and flourishing private school’. The connection with Arnold was still close, and a letter from his son, the poet Matthew Arnold, about a visit in 1848 to the man he still called Uncle Buckland gives an idyllic picture of the establishment as it then was. ‘In the afternoon I went to Penton Hook with Uncle Buckland, Fan, and Martha, and all the school following behind, as I used to follow along the same river bank eighteen years ago. It changes less than any place I ever go to.’7

But the memories of a man in his mid twenties, however little the place itself seemed to have changed, were more pleasant than the day-to-day reality for the thirty or so small boys at the school. Even Arnold, in a less lyrical mood, described it as ‘a really bad and injurious school’, and grumbled about ‘that detestable gravel playground’,8 while ‘Uncle Buckland’ gloried in a reputation for strict discipline that was anything but avuncular.

One former pupil – who went on to become a bishop in New Zealand9 – recalled how he was summoned from breakfast by Buckland to be asked what religion he was. ‘Christian’, apparently, was not a good enough answer, and when the boy stammered nervously that he did not know ‘what sort of Christian’ he was, he was sent off to spend the day locked in the cellar. Eight hours later ‘Uncle Buckland’ unlocked the door, and asked him again – and still the panic-stricken boy had no reply for him. ‘The headmaster replied at last, “Sir, you are a Protestant,” and knocked him down. Hardly a method to encourage Protestantism, the bishop thought, looking back …’

And not one either to encourage a happy atmosphere of learning and scholarship. Doughty was experiencing early the violent religious bigotry that he would meet again in the deserts of Arabia: it is hardly surprising, even though the victim of that attack made his career in the Church, that many of Buckland’s pupils, like Doughty, adopted an ambiguous attitude to the established religion as they grew up.

But Buckland’s no-nonsense attitude would have raised few eyebrows in the mid nineteenth century. The only complaint about the school that Doughty himself made as he grew older was a much less serious one, his wife wrote in a letter, years afterwards. ‘He was six years old, and much resented being made to get out of bed to show visitors what a tall boy he was.’10

His guardians positively welcomed the strictness of the regime, and around the time that Buckland retired they moved their young charge away from Laleham and off to the nearby school at Elstree. It was a move from one strict disciplinarian to another, even more overbearing one.

Once again, it was a quiet, country establishment, in a seventeenth-century mansion at the top of a hill, with a Spanish chestnut tree said to be over a thousand years old outside the front door – the tree, its huge, contorted branches now severely pruned, still stands outside what is now a nursing home. The curriculum was mainly classics, with a few periods a week of mathematics, occasional science lessons, and desultory French from a visiting Frenchman. There was a gravel yard with a fives court, football from time to time, and cricket on the field in front of the house.

Doughty had a slight stammer, which was to stay with him throughout his youth. He was tall for his age, but slim and unassuming, although his contemporaries were already finding out that his apparent frailty concealed a deceptive strength and determination. Two of them who met his wife shortly before her marriage told her that, thin and delicate as he was, he had fought and beaten all of them.11 In another incident, presumably during one of the cricket sessions across the road from the School House, he was hit in the face by the ball. His wife told the story after he died: ‘No notice was taken at the time, and he said nothing (so like him!) but the cheekbone was smashed, which showed all his life.’12

On another occasion, he had told her about competing with a group of boys to see who could stand longest on one leg. He was left standing there when they all went off to church – and he was still there on one leg when they came back.

It is probably as well that the Revd Leopold Bernays knew nothing about one of his young charges spending his time in such fruitless vanity when he should have been at prayer. Letters about the headmaster ‘do not give the impression of a genial or popular man’, notes the Elstree School history coyly – and, judging from the sermons that he published during his life, he must have been an awe-inspiring, even terrifying, figure for a young boy. ‘Nothing can make life sweet and happy but a constant preparation for death,’ was one of his more jovial bons mots;13 in another sermon he stormed at the wide-eyed ranks of small boys before him: ‘If we could see the very jaws of hell open to receive us, and ourselves hastening madly down the road, with nothing to arrest our career – how we should pray!’ Again, he pondered on how ‘one week passed amongst you pains me, with its long catalogue of idleness and carelessness, of disobedience and wilfulness, of harsh and profligate words …’14

Most of these idle, disobedient and wilful pupils were destined for Harrow School, but Doughty’s ambition, even at his young age, was to follow the tradition of his mother’s family and enter the navy. His brother Henry had already been at sea for two years, and Charles wanted nothing more than to follow in his footsteps. Some time around 1856, a boy of around thirteen, he was uprooted from school and friends for a second time, and bundled off to Portsmouth, where he was to be prepared for his navy examination at a school called Beach House.

Henry was to leave the navy later for a career as a lawyer. But his future was mapped out for him, as the future squire of Theberton; as the younger son, Charles would have to fend for himself. Life as a naval officer must have seemed to combine excitement with the sense of patriotic duty that had been bred in the young boy’s bones – and, too, with the severely practical need for a career.

It was not only the example of his mother’s family that had inspired the two Doughty boys with the idea of serving in the navy – for all their seniority, the much-boasted six Hotham admirals would have seemed remote to a small boy, an inspiration to duty rather than passion. But there were other family stories to whet their appetites – most particularly, those of their cousin, the journal-writing Frederick Proby Doughty of Martlesham.

He was only a few years older than they were and had already sailed to Canada, South America, Easter Island and even off to the Baltic to fight against the Russians. Here was a hero with whom they could identify. Though they saw him rarely because he had been away at sea since passing his exams some ten years before, they must have been well aware of his stories and adventures. They did, after all, spend at least some of their holidays with his father, their guardian, Frederick Doughty.

Much of the time, though, the boys were farmed out to a succession of relatives. Theberton Hall, the house where they had been born, and one of the few constant elements in a life that had so far been a series of uprootings and removals, remained locked up. A caretaker and his family lived there, among the gloomy, half-finished building works that were their father’s memorial, to look after it until Henry should come of age to take over his inheritance.

Sometimes they stayed with the Newsons, a family who had farmed on the estate for generations, sometimes with their father’s sister Harriet Betts and her family, who lived nearby in Suffolk – ‘a thoroughly scheming, worldly person’, if Frederick Proby Doughty is to be believed – and sometimes, too, with their mother’s relatives, the Hothams, who also lived in Suffolk.

Certainly there were happy memories among all the travelling between relatives’ houses: in his old age Doughty recalled fondly ‘the noble castle ruins and proud church monuments’ of Framlingham. ‘It is to me one of the memories of childhood, when my mother’s father was Rector of Dennington, two miles further on,’ he wrote.15

Frederick Proby Doughty has left details of one family holiday which he spent with his parents and his cousin and future wife Mary Arnold – with the fourteen-year-old ‘Charlie’ Doughty acting as unofficial chaperon for the undeclared lovers. Young Charlie at that time was at Beach House and his cousin – who had been at home for several months since his latest voyage – was deputed to collect him from Portsmouth and escort him to North Wales. The long coach journey through Bath and Bristol to Llangollen gave plenty of time for the young man’s tales of life at sea – and his teenage cousin would have been an avid listener.

For the two young lovers, it was an ideal family party. The older Doughtys left them to their own devices – they, after all, wanted a quiet, dignified time in a respectable hotel, rather than long walks in the country. And even when their young cousin tagged along, he had better things to do than interfere. ‘Charlie was ever alive to the chance of catching a trout … Better elements for leaving Mary and myself to our own devices could not have been collected together,’ says the journal gleefully.

The young people spent most of their time rambling over the hills – again, little sign of Doughty’s supposed frailness. ‘Charlie and myself did Beddgelert, and passed over the top down to the pass of Llanberis, and so back to Beddgelert – a walk of over thirty miles. We had been rewarded by a good view from the top of Snowdon.’ But if the days were long and energetic, the journal also gives a telling glimpse of what must have seemed to the young people to be equally lengthy but tedious evenings. ‘As a family, we are not a festive lot, and, left to ourselves, the sun might travel from its rising to its setting without one observation being made … The more genial spirit of my father, as I remember him, seemed by the habitual staidness of his life to have almost died out.’

Frederick’s innocent suggestion of a quiet game of cards caused an outburst from his mother: it showed a vicious spirit, and a tendency towards gambling, she stormed. It’s a hint of what life at Martlesham must have been like for much of the time – these, after all, were the people who thought the Revd Leopold Bernays a suitable moral guide for their young charge.

As a whole, though, the month in Wales passed happily – the best times, even at this young age, were spent away from wherever happened to be ‘home’ at the moment. Frederick Doughty recalled it years later as ‘a very jolly cruise’, and ‘Charlie’ clearly enjoyed spending time with a cousin who seemed, at twenty-two, to have such a wide and enviable experience of the naval life on which he was himself about to embark.

From Llangollen, at the end of the holiday, he returned to Beach House, and his preparation for his naval examinations – and to a shock and disappointment that was to remain with him all his life. When he was finally entered for the medical test that formed part of the entrance requirement, he was turned down by the examiners, either because of his slight speech impediment, or because his general health was thought not to be strong enough for the rigours of life at sea. More than sixty years later the memory still hurt him. ‘My career was to have been in the navy, had I not been regarded at the Medical Examination as not sufficiently robust for the service. My object in life since, as a private person, has been to serve my country so far as my opportunities might enable me.’16

His rejection seems to have shocked the staff at Beach House as well. During the following year his maternal aunt, Miss Amelia Hotham of Tunbridge Wells, was assured that he was ‘the very best boy that we have met with’. Even allowing for a degree of tact in dealing with pupils’ close relatives, it is a verdict that suggests that Doughty’s teachers, at least, believed that the navy had missed a good candidate.

Their sympathy, however, must have been of very little consolation to a boy who had seen his ambition snatched away from him, whose elder brother had by now started a career at sea, and who was still all too conscious of his cousin’s steady progress in the service. It must have been hard, too, to be surrounded by his contemporaries, who would have been looking forward to their own careers as naval officers. A few months after the examination board’s decision he was taken out of the school, and started a course of study with a private tutor.

Clearly, he and his family had decided that if he could not follow one family tradition by joining the navy, he should follow another by going up to his father’s old college at Cambridge, Gonville and Caius. Preparation for that involved a degree of formal, structured study, and the records of King’s College, London, show the young Doughty lodging in a suitably respectable boarding house in Notting Hill,17 while he followed a mathematics evening course at the college.

But Doughty remained the prosperous son of a prosperous family, and much of the time between Beach House and Cambridge, his widow said later, was passed in travelling with his tutor through France and Belgium. They were travels that not only gave him his first taste of foreign languages outside the classroom, but also established the connection in his mind between study and the wandering life. Perhaps it was on the roads of northern France that much of the character of the scholar gypsy was formed.

More crucially, though, he returned to the chalk countryside of his home in Suffolk. During his school holidays at his uncle’s home in Martlesham or on the Newsons’ farm in Theberton, he had amused himself by digging for fossils and stone artefacts – a very fashionable pastime as the revelations of Charles Darwin about evolution were echoing around the world. Now Doughty started geological and archaeological studies in earnest around the village of Hoxne – ‘working a good deal with the microscope’, he told a correspondent later.18 In 1862, while still only nineteen years old, he submitted a paper to the Cambridge meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science on Flint Implements from Hoxne.

It was an ideal place to start. More than sixty years earlier the little Suffolk village, recognized today as one of the most important archaeological sites in Europe, had seen the discovery of some of the first stone axes found in Britain; in 1860 those discoveries were being linked with others made in France, to revolutionize the accepted view of prehistory. Humanity, the researchers demonstrated, had a much longer pedigree than anyone had believed.19

It was a controversial, even revolutionary subject, and the decision Doughty made now reflected the self-reliance that had been forced on him by a bleak and lonely childhood, the toughness that the disappointment at Beach House had given him, and the straightforward determination that was already a part of his character. Practically everyone who came into contact with Doughty throughout his life commented on his diffidence – his friends were later to refer to him dismissively as a ‘shy dreamer’20 – but his arrival at Cambridge University showed that his reserved manner hid a rocky determination.

The Admissions Book in the archives of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, shows ‘Carolus Montagu Doughty’ accepted as a new member of the college on 30 September 1861. It was the college that his father and his grandfather had attended before him, but Doughty was determined not simply to follow in their footsteps. It was only two years since Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species had outraged the certainties of the Established Church with which Doughty had such close family links, and the study of science was still considered barely respectable in the university – and yet it was on the newfangled Natural Science tripos that he decided to concentrate.

His expeditions and diggings in Suffolk had already made him a dedicated geologist and collector of fossils, and he was determined to develop this interest from the start of his Cambridge career. It cannot have been a welcome ambition in a family as steeped as his in the reassuring traditions of Church and countryside.

It is Darwin who is chiefly remembered today as the man who shivered the comfortable theology of the Church of England to its foundations, but more than twenty-five years before On the Origin of Species appeared, Charles Lyell had dealt another blow with his Principles of Geology. It is hard to overstate the impact of the new science on the intellectual life of the time: Lyell’s contention that the earth was still changing and developing after hundreds of thousands of years had broken upon a world where eminent churchmen referred to ancient texts and confidently named 23 October 4004 BC as the precise date of Creation, while Darwin’s challenge to the story of Adam and Eve seemed to strike at the very basis of Christianity.

People struggled to hold onto their faith, and John Ruskin spoke for many of them when he declared, ‘If only the geologists would let me alone, I could do very well – but those dreadful hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses!’21 And the geologists themselves felt the draught of their studies upon their own beliefs. In a letter to Darwin, written in the mid 1860s, Lyell said wistfully: ‘I had been forced to give up my old faith without thoroughly seeing my way to a new one.’22 It was a common dilemma, and one which struck particularly hard at a young man like Doughty, passionate in his sense of tradition, yet unswerving in his search for truth.

Doughty had grown up with the rhythms of the Authorized Version echoing in his mind, and his whole instinct was to look back, not forward, for reassurance – but it was in that dreadful clink of the geologist’s hammer that he found inspiration. The whole discipline of geology, and the study of natural science itself, was unsettling, revolutionary, and frequently in direct conflict with the teaching of the Church – but it fascinated Doughty.

As a child, he had been gripped by the idea of the navy and his family tradition of military service. Later, it would be Arabia, and then the story of the Roman conquest of Britain. Doughty would continue to focus his attention upon some particular subject and, over a period of years, would immerse himself in it, teasing out every last detail, before passing on, his attitude to life altered and enriched by the experience, to some new study. Time was not significant – the writing alone of The Dawn in Britain took almost ten years of his life, and the research beforehand at least as long again – but while the fascination was upon him, his obsession would be virtually total.

The shy and diffident young Doughty seems to have made little impression in his early days at Cambridge. He found it hard to make friends with his fellow students – and at the same time he showed no sign of incipient brilliance as a scholar. The Caius examination records show him stumbling uneasily through his first examinations – 27th out of 32 in Classics, 19th of 34 in Theology and, despite his efforts at King’s College, London, 30th of 35 in Mathematics. But from the very start there was no doubt where his greatest interest lay.23

He clearly enjoyed passing on his geological passion: he dragged one of the junior fellows of the college, Henry Thomas Francis, off to inspect the Kimmeridge clay at Ely and the gravel pits in Barnwell (‘When’, Francis recalled wryly later, ‘I caught a severe cold …’). Another friendship was with the future Professor John Buckley Bradbury, with whom he shared a staircase in Caius overlooking Trinity Street – Doughty’s old room, which has since been redeveloped, was above the college library where, decades later, the main collection of his private books and papers was held. The two men used to take long walks into the country, visiting the chalk pits and coprolite diggings just outside Cambridge.

Another contemporary at Cambridge, Edwin Ray Lankester, later to become a Fellow of the Royal Society and one of the country’s leading zoologists, also recalled Doughty’s application and enthusiasm. For a time Doughty had rooms opposite his, and Lankester remembered him, three years his senior, as ‘rather shy and quiet, but very kind and anxious to help me’.24 The unassertive, awkward young man still spent much of his time and money digging at Hoxne. ‘Doughty did not take part in such things as rowing, but was always reading geology and philosophy,’ he said.

But before he could specialize in his chosen subject. Doughty had to pass the Cambridge first-year examination, the so-called Littlego. The Greek and Latin which had to be dealt with he treated with a certain amount of disdain, doing the work that was necessary without, apparently, much enthusiasm. Sixty years later his colleague of the gravel pits and the Kimmeridge clay, Henry Thomas Francis, remembered teaching him Classics.

Doughty as an undergraduate was shy, nervous, and very polite. He had no sense of humour, and I cannot remember that he had any literary tastes or leanings whatever. He read Classics with me for his Littlego. He knew very little Greek. When he came up, he was devoted to Natural Science generally. He had made a large collection of Suffolk fossils, and was rather combative in favour of the new studies. He did not like attending lectures.25

Francis also recalled a visit from another undergraduate who announced that he was no longer going to take lessons in Classics from him.

I said, ‘Very well, but what are you going to do?’ and after a little hesitation he replied, ‘The fact is, my friend Doughty tells me you bother one with grammar and all that sort of thing, and that it is far easier to get up the whole business by heart.’ My answer was, ‘Then we are right to part, for I can’t teach Latin or Greek on those conditions.’