Полная версия

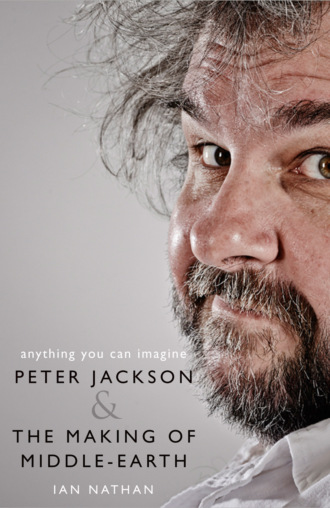

Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-earth

In an absurd hangover from the project’s brief tenancy at MGM, which would have a huge bearing in the future, the rights to make a filmed version of The Hobbit remained with the studio. The rights to distribute such a film were now the preserve of Saul Zaentz.

Reconsidering his version as two films — Zaentz’s financial largesse went only so far — Bakshi still intended to embrace the volume of Tolkien’s book, capturing the scope and violence of Middle-earth. He felt children would want to be scared, and adults appreciate the sophistication of Tolkien as seen through his eyes.

As was his wont, Bakshi’s approach was far from traditional. For the heft of the world, the ranks of Orcs and men, he pursued a technique known as rotoscoping. In simple terms the animator traced over live footage for added realism. Live-action scenes of extras made up with animal horns, teeth and dressed in furs as Orcs and Nordic-looking riders were shot on the plains of La Mancha in Spain before animation began (Belmonte Castle stands in for Helm’s Deep). While static, the heavy, inky backgrounds have the gothic imprimateur of Gustave Doré woodcuts. Slashed with brushstrokes, the intensity of Bakshi’s apocalyptic imagery can be hard to shake.

In the portrayal of evil he revealed his grasp of Tolkien. The Nazgûl snuffle like bloodhounds, their limbs convulsing in their drug-like craving for the Ring. The interpretation of an alien-looking Gollum, voiced with an unforgettable toddler’s wail by the English actor Peter Woodthorpe was, until Andy Serkis coughed up his hairball performance, definitive.

But Bakshi would later wail that he had been under intense pressure over time and budget (estimated at $8 million). He was forced to cut corners, compromise his vision. The clichéd foreground figures are often no better than Hanna-Barbera cartoons: Frodo, Merry and Pippin are virtually identical; Sam looks like a melted gnome; and the Balrog is a laughable bat-lion hybrid. The script by Chris Conkling and fantasy author Peter S. Beagle (who had written an introduction to an American edition of the book) is faithful but abbreviated. Frodo sets forth with the Ring with barely a summary of what is before him, the film chalking off the major pieces at an unseemly gallop before it all grinds to a confusing halt after The Battle of Helm’s Deep, awaiting a sequel that would never come.

Perhaps Bakshi should have been forewarned of growing indifference when the studio removed any mention that this was Part One of two films, which only contributed to the general confusion. The $30 million his film made around the world was deemed insufficient reward by Zaentz and UA and the sequel was postponed forever.2

‘I was screaming, and it was like screaming into the wind,’ lamented Bakshi. ‘It’s only because nobody ever understood the material. It was a very sad thing for me. I was very proud to have done Part One.’

Was the book impossible to adapt? The sheer size of it could have filled out a mini-series. This was War and Peace set in a mythological universe. Scale was an issue on many levels for a live-action version. The lead characters, though fully grown, stood four foot tall at most. There was a host of exotic creatures: Orcs, trolls, mûmakil — elephants on growth hormone — giant eagles, Ringwraiths, grouchy arboreal shepherds called Ents, and fell beasts like winged dinosaurs. Then there was Gollum, who was less part of the peregrine biosphere than a fully rounded character, arguably Tolkien’s most vivid creation. And what of those battles, swarming with untold armies? Sergei Bondarchuk’s 100,000-strong 1966 adaptation of War and Peace had the Red Army at its disposal.

If animation was the only realistic approach, it almost inevitably reduced Tolkien’s grandeur to something childish.

Bakshi would have his part to play. In 1978, the seventeen-year-old Jackson raced into Wellington after school to catch the New Yorker’s animated vision. Spectacled, permanently wrapped in a duffle coast and movie mad, he wasn’t any kind of serious Tolkien fan but he was obsessed with fantasy. Like so many who saw it, parts impressed him but he left baffled. Was there to be another film?

‘My memory of the movie is that it was good until about halfway through then it got kind of incoherent,’ he says. ‘I hadn’t read the book at that stage so I didn’t know what the hell was going on. But it did inspire me to read the book.’

Weeks later, due to attend a training course in Auckland before commencing his apprenticeship as a photoengraver, Jackson paused at the concourse bookshop to pick up some reading matter to fill the twelve-hour train journey. There he spotted a movie tie-in edition of The Lord of the Rings.

‘It was the paperback with the Bakshi Ringwraiths on the front. That was my first copy of the book.’

He still has it somewhere.

‘In some respects if I hadn’t seen his movie I might not have read the book, and may or may not have made the film …’

*

In 1996, Jackson’s career was going places. Quite literally: he had made it to the Sitges Film Festival, thirty-five miles southwest of Barcelona. In a satisfying sign that his reputation as a filmmaker was reaching beyond the shores of New Zealand, the annual jamboree devoted to fantasy cinema had invited him to screen his new film, a zombie comedy (or zomcom) called Braindead. Back home, after three peculiar horror films, he was still regarded warily by the establishment.

‘You’ve got to understand that, until Heavenly Creatures, he was an embarrassment in New Zealand. He wasn’t someone to celebrate,’ says Costa Botes, a friend and frequent collaborator through the early days. ‘Because of the films he was making there were certain factions of the industry actively gunning for him.’

Not a natural explorer, Jackson had been reluctant to go. He was persuaded when he saw the guest list. Here was an opportunity to meet some of his heroes in the flesh. Talents who had helped shape him as a filmmaker like Rick Baker, the genius make-up effects specialist feted for the still-extraordinary werewolf transformation in An American Werewolf in London. Or Freddie Francis, the cinematographer who had created the ghoulish, sweet-wrapper hues of the Hammer Horror movies (that cherry red blood that ran down Christopher Lee’s chin). Or Stuart Freeborn, the English make-up artist who had helped design Yoda. Or Tobe Hooper, the young director who had shocked the establishment with his debut horror movie The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

‘At that time Tobe Hooper and I looked quite similar,’ recalls Jackson. ‘Dark, shaggy hair and beards. And Stuart Freeborn couldn’t figure out who was who. I would go down to breakfast, and Stuart would go, “Hello Tobe.” And I would just go, “Hi Stuart.” I didn’t even bother to correct him. It was kind of fun, there was all these interesting characters. That was the only time I ever met Wes Craven.’

Craven was the horror maven who began the Freddy Krueger phenomenon with A Nightmare on Elm Street at New Line.

Grouped in the same hotel, guests would congregate for breakfast and dinner, guaranteed to find an available seat alongside a fellow traveller. Jackson and Fran Walsh instantly bonded with Rick and Silvia Baker. They would head out for walks along the cliff-top where the views of the Mediterranean were stunning.

‘But there was this really pushy American guy who would tag along with us,’ says Jackson. ‘We’d be literally heading out the door and he would be there: “Do you mind if I come too?”’

Naturally, there were a lot of fans around, begging signatures and photos, proof that they had met their heroes (or heroes to come).

‘We got to the point where we wanted to sneak out of the hotel and not have this guy follow us. I didn’t know who the hell he was.’

Then one afternoon he asked if they were coming to see his film.

‘Oh, you’ve got a film?’ said Jackson, taken aback. ‘You’re not a fan?’

‘Yeah, yeah, yeah,’ he replied, the words rattling out of his mouth like winning coins from a slot machine. ‘I’ve got a film! It’s called Reservoir Dogs.’

Twenty-five years later, Jackson howls with laughter. ‘It was Quentin Tarantino … I remember that when it got to the ear-cutting scene, Wes Craven stood up and walked out because he couldn’t handle it. And Quentin was saying, “This is the greatest thing in the world, Wes Craven walked out of my movie.”’

Reservoir Dogs would be picked up for distribution by a small American indie, Miramax, named after the owners’ mother and father, where this Angelino video-store clerk turned frenetic, inspired, outrageously brilliant filmmaker would be nursed toward greatness. That same company would swoop for Jackson as well in the not-too-distant future.

Also on the list of that year’s festival was Bakshi.

They didn’t socialise. Bakshi showed no interest in that side of things, remaining aloof from the gaggle of eager filmmakers, his career in the doldrums by the early 1990s. Maybe it was because he was more distant than the others that Jackson requested a picture with the director of The Lord of the Rings. It wasn’t something he asked of anyone else — he was a peer now not a fan.

‘He didn’t have a clue who I was.’

Years later, he would. However, unlike Boorman and McCartney’s gracious approval, Bakshi responded to Jackson’s success with indignation. Why hadn’t he been sought out for the benefit of his wisdom? Asked to be involved? He turned bitter in interview whenever Jackson’s films were brought up. Some wounds never heal.

‘I heard reports that they were screening it every single day at Fine Line,’ he smarted, erroneously citing New Line’s arthouse division as having been voraciously cribbing from his film. Which wasn’t true anywhere in New Line.

Jackson remains perplexed that there should be any ill will between them. ‘I’ve read those interviews with him and he is incredibly angry. These really bizarre interviews where he said, “I’m insulted that Peter Jackson never consulted me, because I am the only other guy that had done The Lord of the Rings and he didn’t give me the courtesy of talking to me.” Why would I do that? What was there to gain from it? It was odd. I can’t even understand it from his point of view. Why would I need to speak to the guy who made a cartoon version of it? And conversely why would he expect me to?’

Maybe it was simply envy: he got to finish the story.

‘I know,’ says Jackson not unkindly.

It was also while in Sitges that he and Walsh heard that the New Zealand film commission had finally agreed to finance Heavenly Creatures. And Heavenly Creatures is where everything changed.

*

New Zealand first heard the infant cries of Sir Peter Robert Jackson on 31 October 1961 — Halloween, no less — in Pukerua Bay, a sleepy coastal town frozen in the 1950s some twenty miles north of Wellington. His doting parents, Joan and William ‘Bill’ Jackson, by every account delightfully forbearing towards the whimsical pursuits of aspirant filmmakers, were first-generation New Zealanders, emigrating from England in 1950.

Pukerua Bay offered an embryonic Oscar-winning filmmaker few outlets for his furtive, restless imagination. He forwent university, film school was unimaginable, and after some aborted attempts to involve himself in the New Zealand film community, he began his professional career working as a photoengraver for the Evening Post in Wellington.

According to legend, the biggest inspiration to Jackson and on his determination to become a filmmaker (if not yet a director) was encountering Merian C. Cooper’s and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s 1933 King Kong at the tender age of nine on the household’s humble black and white television. It was late to be up, nine o’clock, but he was enraptured by the wonder of it all: this tale of a giant ape on a lost island that also happened to be populated by dinosaurs, who was then captured and brought to New York — Eighth Wonder of the World! And how he perishes, plunging from the Empire State Building. For Jackson, changed forever, it was everything an adventure story should be.

To gain a measure of how much King Kong means to Peter Jackson, leap forward to December 1976, about the time Bakshi began half-making The Lord of the Rings. At seven o’clock on a sleepy Friday morning, the fifteen-year-old Jackson had caught the first train into Wellington worrying over the length of the queue that would be forming outside the King’s Theatre cinema on Courtney Place.

He was there for the first showing of the remake of King Kong, a production he’d been following for months in the pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland. But the cinema was still locked up and Courtney Place was as deserted as it would one day throng with delighted thousands as Jackson made his lap of honour in an unforeseeable future.

‘I kind of bought into the hype,’ he laughs — that boy was such a dreamer. ‘I convinced myself there would be crowds and crowds of people. There weren’t. And, like most people, I was disappointed by it.’

The film is a wreck. Big-talking mini-mogul Dino De Laurentiis, cut from similar cloth to Saul Zaentz, had boasted of using a forty-foot robotic gorilla that could scale buildings, but the technology had failed him and its motion was never captured. In the finished film it is Rick Baker in a suit. The modern setting, the absence of dinosaurs, the flat, un-wonderful ambience generated by journeyman director John Guillermin (The Towering Inferno) bespoke of all that could fail in a film.

The disappointment of the King Kong remake would teach Jackson a valuable lesson, and he saw it six times. You must never forget that fifteen-year-old, too early, waiting in the cold.

The presence of Kong would cast a huge shadow over Jackson’s career, but even having finally made his own spectacular remake in 2005 (another long, wending, troubled journey to the screen), it is to The Lord of the Rings the fifteen-year-olds of all ages and sexes came back again and again, breathless in anticipation.

It was actually the year before he first saw King Kong that an eight-year-old Jackson began shooting films. With a growing interest in special effects already stirred by a steady diet of Thunderbirds, television’s Batman and the epochal moment his neighbour Jean Watson, who worked at Kodak, gave him a Super-8 camera, he also looked upon King Kong as much as a technical triumph as an emotional journey.

‘A year after we met, he showed me a Bond parody called Coldfinger that he’d made when he was fifteen or sixteen,’ remembers Botes. ‘He’d copied the editing of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. And he played James Bond himself. I thought, “This is uncanny — he actually looks like Sean Connery.”’

Jackson built a filmmaking career with his own hands. A fleet of homemade shorts, inspired by his love of King Kong, Ray Harryhausen and James Bond, would grow (or perhaps the word is mutate) into his first feature film — Bad Taste.

Made in fits and starts over four years, and because of day jobs, only on Sundays, Bad Taste began life as the short, Roast of the Day (the powerful tale of an aid worker encountering cannibal psychos in deepest Pukerua), and slowly sprouted into a feature film. Doffing a windblown forelock toward Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead, Jackson’s unhinged tale of a group of aliens plotting to turn humanity into fast food, would be a test of his native ingenuity and fortitude to rival that of The Lord of the Rings.

Roping in friends and colleagues from The Evening Post, cast and crew came and went over the ensuing years, written out then written back in again, Jackson more or less making it up as he went along. His parents provided the $2,500 to buy a 16mm Bolex camera. Everything else — prosthetics, special effects, Steadicam rig, props, alien vomit, stunts, acting — was homemade.

At one stage, Jackson, in the prominent role of the nitwit alien investigator Derek, would dangle himself upside down over a local cliff, a rope tied around his ankle the other end attached to a wooden post. Health and safety were for those who could afford them. He only hoped his friends would pull him back up again. If that post hadn’t held, The Lord of the Rings may linger to this day unmade.

‘It crushed all the nerves in my foot,’ he laughs; ‘it took about six months for the sensitivity to come back.’ Which might account for his nonchalance toward going barefoot on the roughest terrain.

Halfway through, they all went to see Robert Zemeckis’ thriller Romancing the Stone, then almost killed themselves replicating the sequence where Michael Douglas plunges downslope through the bushes.

Eight years later Jackson would be working with Zemeckis.

There were also times it tested Jackson’s emotional reserves. One Sunday, dropped off on location by his parents with all the props and costumes, no one else showed up. He just sat there all day. When his parents came to collect him at 5 p.m., he was close to tears. It was a lonely lesson in always working with people you could depend on.

Bad Taste would be his film school. And a film would emerge, half-crazed but hilarious, gurgling with its own outrageous pleasure at the raw act of creation. Following another arduous test of his patience, it would find distribution and stir up a cult following that exists to this day, hanging on to the hope that Jackson will eventually make good on his promise to make a sequel or two.

Significant to this tale were two key friendships that Jackson formed because of his Bad Taste. Richard Taylor, who along with his wife Tania was making puppets for a satirical Spitting Image-style New Zealand television show called Public Eye, had heard about this guy out in Pukerua Bay who was making a sci-fi splatter movie in his basement. ‘We really wanted to meet him. It turned out that his sci-fi movie was called Bad Taste. He was baking foam latex in his mum’s oven.’

Taylor would join forces with Jackson on his very next film, and begin his own journey toward The Lord of the Rings.

And this was when Jackson first met Fran Walsh. To be exact, he first saw Walsh on the set of the series Worzel Gummidge Down Under, the television offshoot about a talking scarecrow, for which he had been hired to do a few little special effects. She was one of the writers, but they hadn’t spoken. Then out of the blue Botes asked if he could show the unfinished Bad Taste to a couple of his screenwriter friends, he thought would appreciate it. They happened to be Walsh and her then boyfriend Stephen Sinclair. Walsh remembered being bowled over by how uninhibited the film was, and on zero budget.

She would volunteer her services to help complete the film, and would become not only the most important creative partner in Jackson’s life but the story of this book.

Completing Bad Taste, says Taylor, ‘Peter was bitten by the bug.’ Up until then he had thought he might get by in special effects. In New Zealand the thought that you could follow a career as a director was preposterous. But the response to Bad Taste was so powerful that it convinced Jackson this was his calling.

Jackson also committed himself to gore, and ruffling the strait-laced New Zealand film community. In 1989 came depraved puppet musical Meet The Feebles (shot in a rat-infested warehouse) followed in 1992, after a salutary false start, by Braindead, his blood-bolstered, period zomcom. The film that would take him to America — if only for a visit.

A career had been born in a deluge of sheep brains, farting hippos and a zombie baby named Selwyn. Middle-earth was another world.

‘When he finally made enough money to move into town,’ remembers Taylor, ‘it was into the tiniest house in Wellington. He bought the biggest television I have ever seen and we’d sit in his front room, dwarfed by this gigantic thing. When you stood up to make a cup of tea, there’d be half a dozen people out on the pavement, standing there watching the movie!’

*

There is one other adaption of The Lord of the Rings we have yet to mention. Indeed, it was the most comprehensive and meaningful adaption to date, one that is still held in the highest esteem by fans. It was also the only version of the book to provide any objective lessons — apart from what not to do — in how to successfully dramatize Tolkien, even though there was not a single frame to be seen.

This was, of course, the 1981 BBC radio serialization. Adapted by Brian Sibley and Michael Bakewell with a fine-edged scalpel, trimming great swathes of the book without any discernible loss of the central story (it still runs to a considerable eighteen hours). They also retained a good deal of Tolkien’s dialogue, while carefully negotiating the demands of radio dramatization. Events that are reported in the book are transformed into first-hand scenes (a trick Jackson and his writers would apply). Even the battle scenes, inevitably reduced by the medium, have a dense, breathy, clanging atmosphere. All of it eased onward through the addition of a narrator (Gerard Murphy).

Above all, the vocal performances set an enviable standard: Michael Horden swings appreciably between avuncular and steely as Gandalf; Robert Stephens’ smoky basso makes Aragorn seem older, wiser and immediately kingly. Jackson would seek a deliberate resonance between the serial and his own films in the casting of Ian Holm as his Bilbo; Holm having made an impassioned Frodo back in 1981.

Having made his mark in Bakshi’s adaptation, Peter Woodthorpe would again provide the disturbingly funny duality of his Gollum. Disembodied, that needling, pathetic, hissing voice carries a note of pure heartbreak.

The seminal serial was responsible for bringing another generation to the book. But Hollywood had lost interest or grown weary of its numerous challenges. And for fifteen years the Ring lay forgotten, until it was finally picked up by the most unlikely director imaginable.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.