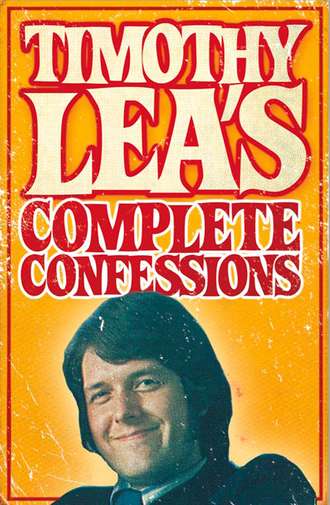

Полная версия

Timothy Lea's Complete Confessions

“That’s diabolical, I mean its not as if you’re unattractive.”

“I’m not asking for compliments.”

“I wouldn’t say it unless I meant it. I think you’re a very handsome woman. Your old man doesn’t know how lucky he is.”

I can see she laps this up and it’s the first real lesson I learn about chatting up birds. If you’re stuck for something to say tell them they’re beautiful. They’ll always believe that. Even if you’re stuck with some right old slag, find something about her that doesn’t turn your stomach and say “Has anybody ever told you what smashing eyebrows you have?” or “Doreen, I never noticed your ears before, they’re beautiful”. Chances are they’ll be peering at themselves in the mirror for the rest of the evening and saying “He’s right, he’s right”, and they’ll be eternally grateful – or, at least if not eternally, you stand a good chance of getting your end away in the bus shelter on the way home.

Another thing to remember about married birds is that none of them reckon their old men appreciate them. Tell them this and you’re backing up their own judgement as well as flattering them, which can’t be bad. Anyhow, in this particular situation the bird’s hand is shaking with excitement as she pours me another cup of tea and I’m sitting back feeling I’ll soon have to start taking ugly pills.

“You know who you remind me of?” she says all intense like.

“Boris Karloff?” I say, modestly.

“No, stupid. Jackie Pallo.”

Jackie Pallo. I don’t reckon that very much. “Nobody’s ever told me that before.”

“It’s your body.”

“You haven’t seen my body.”

“I’ve seen enough of it to tell.”

“I don’t look a bit like Jackie Pallo.”

“Oh yes you do, look, I’ll show you.”

She pops out and comes back with a bloody great scrap book of male pin-ups going right back to people like Dana Andrews and John Payne. They must have been stuck in when she was a kid. Most of the up-to-date ones are telly stars and she certainly goes for beefcake. There’s hardly a bloke with a stitch on above the waist.

“There you are.” She points to a photo of Pallo standing on some poor berk’s chest with his hands clasped above his head.

“I don’t see it.”

“You must do.”

“I’m not very flattered.”

“You should be, I think he’s smashing. I go all – oh, I don’t know – when I see him.”

“Well, I am flattered then.” I puts my hand on her thigh and gives it a squeeze. She doesn’t touch my hand but looks right past me and her bottom lip starts trembling. I take my hand away.

“I’ve got another one somewhere. I think it’s upstairs.”

“I’ll help you look for it.”

“It’s a bit of a mess up there.”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“I think it may be in the kids room.”

“Let’s look there.”

She’s going up the dark stairs ahead of me and I can hear her stockings swishing against each other. Round the bend on the landing and I can see the line of her bra and the bulge of its clip against the small of her back. I’m getting so worked up I can hardly wait to get through the door.

“Now, where did I see it?”

It’s a small room with two kids’ beds close together and the walls covered with pictures of Chelsea Footballers flashing their muscles and looking sickeningly confident. I know how they feel.

She drops on one knee, between the beds, and I’m down there with her like her own shadow. She starts rummaging around a pile of comics and when she turns round I’m right on top of her. I try and kiss her but she pulls back and puts her hand on my arm.

“What are you trying to do?”

“I’m trying to kiss you.”

“Oh, you mustn’t do that.”

This is another little performance you have to learn to get used to. A bird will sandbag you and drag you back to her place but once she gets you there she’ll suddenly start acting all coy and saying things like “do you really think this is a good idea?” or “you just want me for my body”. Bloody stupid, unnatural things that make you want to say “alright then” and piss off. But of course you never do because by that time you’d put a ring on her finger to get your end away.

“Oh, let me kiss you,” I bleat, “don’t be cruel. I think you’re smashing, I really do.”

She makes a bit of token resistance and then comes down on both knees to make herself more comfortable.

“Suppose my old man were to come home?” The minute she says that I know I’m in like Flynn.

“He couldn’t say anything could he. He neglects you.”

I put my hand up her skirt and start kissing her again. She’s good at that and allows herself a couple of satisfied moans.

“You can’t stay long, the kids will be back from school soon.”

We struggle onto the bed and I start fiddling for the hook on her skirt.

“Close the door first.”

I get up and close the door and she’s lying on the bed with her skirt up round her waist, and her face flushed. I sit down on the edge of the bed and start taking my shoes off. There’s a hair pin hanging down by her ear so I take it out and kiss her very gently.

One thing to remember when you’re undressing in front of a bird is to do it in the right order. Get your shoes and socks off first, then your shirt, trousers and pants, if you wear any. I can never understand all those jokers in dirty photographs running around with just a pair of socks on. Always seems very crude to me.

Anyway, I go through this palava until the bird, whose name I haven’t yet discovered, gets a spot of the full frontals without having to turn her telly on.

“He’s very naughty,” she says stretching out her hand, and it’s a fact that I’m standing to attention better than the brigade of guards. I settle down beside her and after a bit more cuddling, because I’ve been reading my book, remember? I unhook her skirt and start to pull it off.

“There’s a zip,” she says. I find that and we’re off again.

So are her pants and tights. I’m starting to unbutton her blouse when she grabs my hand.

“That’s enough,” she says.

It’s a funny thing that, and its one of the differences I find between upper and working class birds. Your upper class bints likes nothing better than to tear all her clothes off and run around starkers showing you everything she’s got, and proud of it, but most of the stuff I tumble with only take their knickers off. Flashers like Viv are the exception. I don’t know whether it’s because working class families live on top of each other and have to be more careful in case the kids suddenly come bouncing in, or because they reckon the whole thing is a bit dirty and least seen soonest mended. Anyway, this bird is dead typical.

“Go on,” I say, “you’ve got lovely breasts.” Notice I don’t say tits. It’s because I’m trying to be romantic and ‘breasts’ seem the right word to use, but I have since learnt that with an upper class bird you’d be much better telling her she had a nice pair of bristols. They go for it if you talk dirty to them, whilst a bird like this one will go spare if you say ‘cock’ when you’re on the job.

“No,” she says, “you mustn’t do that. You just be nice to me, that’s all.” I know what she means so I drop my hands down below and rummage around in her tea-cosy. It’s as slippery as a snail’s front doorstep and twice as inviting. The very feel of it sends electric currents racing round my old man.

“What’s that?” she says suddenly.

“It’s my hand.” I says.

“No, I meant that noise.”

She half sits up and I stop quivering with excitement and start trembling with fear. Our ears strain into the distance and I hold my breath waiting for the sound of footsteps on the stair.

“I can’t hear anything.”

“No, it must have been my imagination. The house creaks a bit sometimes.”

She drops back again and pulls me down to her.

“Sorry, put him in now. I can feel he’s ready for it.”

The habit of talking about my prick as if its something I take round with me on the end of a lead does not appeal very much but I don’t think this is the moment to point it out to her. She’s stroking me up a treat and she must use the right washing-up liquid because her fingers are soft as putty. I don’t need any more urging and I’m inside her easy as wanking. It’s all very pleasurable except for the creaking bed springs and the feeling that I’m going to come any moment. In fact the bedsprings are a help, because I’m so busy imagining someone creeping upstairs under cover of the noise that it quite takes my mind off sex which in turn stops me from boiling over. It’s a kind of enforced carezza but it can’t last for ever because the bird is becoming increasingly noisy and violent which excites me out of my tiny mind.

“Oh no – yes – go on, go on! oh no – stop! no – I can’t – oh yes, no!”

She rabbits on like this so if you was really trying to do what she wanted you’d go round the twist or jack it in in disgust. Experience has taught me that when a bint is sexed up you might as well forget anything she says. You’re better off just wacking away till you hear the old death rattle – if you stop that’s always wrong.

But I’m skating on a bit. On this particular afternoon in late September it’s me who’s hanging on for dear life. Like the book says I’m trying to think of everything under the sun to stop myself from coming – hobnail boots, Jimmy Young, bulldogs, old gramophone records – but it’s no good. I’m just on the point of surrendering to my baser emotions when the bird starts tugging at my arse as if she’s trying to get the whole bloody lot of me inside her and starts hollering ‘Now, now, now!’ Well that’s it. I accept her advice gratefully and a few moments later I’m lying on top of her damp blouse and struggling to get my breath back. It’s dead ungrateful, I know, but the moment I’ve come I wish I could press a button and make her disappear. I just don’t want to know anymore. It seems bloody ridiculous that I could have been so worked up just a few minutes before. Beneath me the bird gives a little wriggle to tell me that she wants me to move and when I don’t carefully eases herself into a more comfortable position.

“What’s your name?” she says softly.

“Timmy.”

“That was nice, Timmy. I’d almost forgotten what it was like.”

“Yeah, good.” I give her a little squeeze while I’m wondering how to get out. With Viv it was easy. I might have been in the Casualty Department of a hospital. She just gave me a plaster for my foot, we dressed and I went home. Dead simple. As it happens my latest turns out to be less of a problem than I imagined – at least in one way.

“My name’s Dorothy – what’s that?”

This time there is something. The front door slamming and the sound of feet pounding up the stairs – two of them. Kids voices shouting the odds.

“Oh yes I did!”

“You bleedin’ didn’t!”

“Get out,” hisses the bird. She’s off the bed like its white hot, and whipping on her skirt. She rolls up her drawers and tights and throws them on top of the cupboard. Quick thinking. I’d be impressed if I had time.

“Stop them,” I whisper while I fumble for my socks. She’s so red she might burst. She takes one look at me which hasn’t got an ounce of expression in it and goes out fast. I can sympathise with her. It can’t be much fun to have your kids find you on the job with the window cleaner.

“Look at that carpet. How many times have I told you to wipe your feet before you go upstairs.”

“But Mum—”

“Don’t ‘but Mum’ me. You can go right back and do it properly.” I hear her voice and the squeaks of protest descending to the hall. Now, how am I going to get out? I’ll have to pretend that I was cleaning the windows. I haven’t brought any of my stuff up with me so what am I going to use? In a flash of inspiration I remember Dorothy’s knicks and tights. I nip up on one of the beds and fish them down from the top of the wardrobe. There’s a toilet next door so I dip them in that and give the windows a quick rub over. Luckily it’s stopped raining about an hour before so it doesn’t look too stupid. There’s a nosy old bag opposite peering at me round a curtain but I don’t worry about her over much. She can’t possibly see what I’m cleaning the window with.

Downstairs and I shove the undies in the bottom of my bucket and smile at the kids. They look at me a bit old-fashioned though it’s probably my imagination.

“That’s it, lady, fifteen bob if you don’t mind. Thank you very much. Ta ta, be seeing you.”

I hop on my bike and start cycling down the street with the funny feeling that none of it really happened. Round the corner in front of me a bloke of about thirty-five is crossing the road. His hair is beginning to go and there’s a dead fag gummed between his lips. He’s fat and scruffy and looks like about ten million other blokes who have got one of their mates to clock out for them and shuffled home early for Bird’s Eye fish fingers and an evening in front of the telly. I know that if I turn round and watch he’ll go into the house I’ve just left. But I don’t turn round.

CHAPTER FOUR

“What’s this then?” says Mum.

She’s got a packet of ants’ eggs in one hand and Dorothy’s undies in the other. Like a good mum she’s started to hang my rags out over the cooker – nosy old bag. Sid nearly chokes on his eggs and bacon.

“Didn’t you know, Mum,” he says, “Timmy’s the demon knicker nicker of Clapham. Your smalls aren’t safe on the line when he’s about. Don’t you ever read the Sundays?”

From the look on Mum’s face I can see she half believes him.

“What have you got to say for yourself?” she says, shaking the stuff under my nose.

“It’s just a joke, Mum.” I start to say desperately, “I put them there myself for a laugh.”

“You want to see under his bed, Mum,” goes on Sid, “there’s two suitcases full of the stuff. I’ve seen him at night, sitting up and counting it. He keeps a list of it all in a little notebook.”

“Timmy!” I can see he’s got Rosie going now. It makes you realise what your own family really thinks of you. They’d probably believe Sid if he said I had a couple of bodies under my bed. Luckily, Dad is upstairs with one of his turns – that’s when he turns over and says ‘fuck it, I’m going to stay in bed all day’. He’d probably run out and start yelling for a copper if he was here.

Sid holds an imaginary microphone under my hooter and puts on his lah-di-dah voice.

“Tell me, Mr Lea, when did you first experience the uncontrollable urge to steal ladies’ underwear that has made you the terror of S.W.12?”

“About the same time as I felt the uncontrollable urge to shove this bread knife up your bracket,” I say. “For God’s sake, Mum, you don’t believe him, do you?”

“Where did you get those panties from then?” says Rosie.

“I bought them—”

“—he’s dead kinky, too,” interrupts Sid, “Go on, take your trousers off and show them what you’re wearing. You never seen such—”

“Shut up!” I yell. “I bought them for a girl friend but they were the wrong size, so I thought I’d have a little joke.”

“You haven’t got a girl friend,” says Rosie.

“That’s all you know. I don’t tell you everything.”

“She must be a funny shape if they don’t fit her,” says Sid, holding up the knickers. “You could get into them, couldn’t you Rosie?”

“Don’t talk dirty and put those things down.” says Mum. “What I can’t see is why you didn’t take them back and change them if they was the wrong size?”

With everybody in the family a bleeding Perry Mason, I might as well give up. I should have told them that Sid put them there to start off with.

“They wouldn’t take them back because they were worn,” I say.

“You mean she had to put them on before she found they wouldn’t fit?” says Rosie.

“No, he did,” said Sid.

“I don’t know. I wasn’t there.”

“I should hope not,” says Mum, “the very idea.”

It’s amazing how they go on treating you like a kid, isn’t it?

“It all sounds very fishy to me,” says Sid. “I reckon you’d better come clean and open those suitcases. If you took everything back and said you were sorry—”

“He doesn’t want to do that,” says Rosie, “Better to burn them.”

“Everybody’s going to see.”

“Not if he does it at night.”

“Look a bit funny, won’t it, having a bonfire in the middle of the night?”

“Why don’t you all wait till Guy Fawkes day and then get Sid to stand on the fire instead of a guy?” I say. “By God, I’ve never heard such a load of cobblers in my life. Can’t you see that Sid is having you on? There’s nothing under my bed except fluff. I wouldn’t have believed you could have thought so little of me.”

I knock back my tea and push the chair away from the table. They’re all a bit quiet now and Mum and Rosie are definitely looking guilty. I decide to blow my nose to show them how affected I have been by their unkindness and remove my handkerchief with a flourish. Trouble is that in my hurry that morning I have grabbed a hanky down from the clothes line in the kitchen and – yes, that’s right – it’s not a hanky, it’s a pair of Rosie’s drawers. I notice the expressions on their faces first, and honestly, I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. Even Sid looks at me as if I’ve got blood running down my chin. A glance shows me what I am raising to my nose. Light blue, with a touch of grey lace round the bottom. I start to say something but it’s no good. Everybody is still staring at the knickers like they’ve started ticking. I throw them on the table and Rosie shrinks back in her chair. None of them will say a word. I start to speak again and their eyes slowly swing up to my face marvelling that they could have lived with me so long without suspecting. There’s no point in going on so I stumble out.

I don’t know what they say when I’ve gone but I do know that to this day the subject of underwear makes my mother wince and you don’t see any bras or panties hanging up in our back garden.

As the next few weeks go by I realise that there are quite a few Dorothys about, and I begin to be able to recognise the kind of bird who will be asking you to help her move the dressing table from one side of the bedroom to the other, five minutes after she’s opened the front door. She’s usually been married about seven years – take it from me, the seven year itch is no fairy story – and the last of the children has just begun school, so she’s suddenly got a bit of free time on her hands. Her old man is a dead end nine to fiver, and she’s as bored with him as she is with having nothing to do. She’s read all the stuff in the Sundays about wife-swapping and troilism and she reckons that not only must it be alright to do it but that she is the only bird in the world who isn’t. She’s also unlikely to have thrown it around much before she got married so she reckons she missed out there too, and is dead keen to make up for it. Her trouble is that until she’s done it a few times she’s liable to confuse her natural desire for a bit on the side with love, which can stir up all kinds of problems. Once a customer starts baking cakes for you, or slipping bottles of after-shave lotion in your pocket, you’re better off giving it a miss, believe me.

I remember poor Sid going through a very embarrassing period with this bird who started coming round the house and asking if he could do her windows. She was round there about once a fortnight which was bleeding ridiculous. Added to that, she’s always be walking past dressed up as if she was going to her old man’s funeral. Sid was scared to go out of the house and Mum was giving him the old dead eye. She had a bloody good idea what was going on. Luckily, Rosie had this job in the supermarket so she never twigged. God knows what she would have done if she had. How Sid got rid of that piece I don’t know, because he never talked to me about it, but one day I suddenly think I haven’t seen her for a while and that’s the end of it. Since the business with Viv, Sid has kept his activities very quiet and I think he regrets having opened his mouth that first time up at the Highwayman.

One of the most interesting things about the job is the opportunity it gives you to have a shufty at how other people live. Everybody likes having a poke round somebody else’s place to see what they’ve got. My old Mum for instance. Every time there’s a house in the street for sale she goes round there. She’s no intention of moving, it’s just that she wants to see what kind of wallpaper they’ve got and whether there’s an indoor kasi. She’s also potty on going round the nobs’ houses in the country and coming back and rabbiting on about their stuff as if it’s a dead ringer of hers.

“Little fireplace in the kiddies’ room,” she’ll say, “it had exactly the same tiles as our front room. Very similar, anyway.”

I’m a bit like Mum in a smaller way and there was one job about that time that really sticks in my mind. It was up by the common and one day I’m cycling along when this old bird comes running out holding a wide-brimmed straw hat on her head and waving a walking stick.

“Young man, young man,” she calls out. “Are you a window cleaner?”

I feel like saying no, I always cycle around with a ladder in case I forget my front door key, but I don’t, and she says she has a job for me. As I look at her, I notice that what I first thought was a flower pattern on her hat is in fact bird droppings but I imagine she has just been unlucky and follow her into the semi-circular drive of this bloody great house. There’s newspapers and rubbish strewn everywhere and though I’ve been past the place before, I never thought anybody lived there. By the look of the windows, they can’t do, unless they’ve got bleeding good eyesight because they don’t look as if they’ve been cleaned since they were put in.

“It’s gonna cost you a few bob to clean that lot,” I say, because frankly I don’t fancy the job.

“Only the downstairs windows,” she says. “We’re all downstairs.”

That strikes me as being a bit funny because I can’t imagine a lot of people living there. Maybe they are the survivors of a Victorian hippie commune who can’t stand heights. Anyway, we haggle a bit and I agree to do the downstairs windows for a couple of quid. I’m following her up the front steps when I take a butchers through one of the bay windows. I can hardly see anything they’re so dirty, but there seems to be a lot of movement at floor level which puzzles me. I start to take a closer look but the old bird – “My name is Mrs. Chorlwood” – sends me round the back sharpish. “I’ll open the back door for you,” she says. “I don’t want you frightening them.”

Them? What has she got in there? I move round the house very careful-like, and something knocks against one of the windows from the inside which gives me a start, but I can’t see anything. The garden must have been very nice once, but now it’s all overgrown and there are weeds pushing through the concrete in the bottom of the dried up ornamental pond. I’m surprised they haven’t torn the whole place down and built a block of flats there.

When I get round the back, Mrs. Chorlwood is waiting for me and that’s not all. There’s a pile of empty catfood tins large enough to have fed half Brixton. They pong a bit, too, but that’s nothing to what I find in the kitchen. A large saucepan is bubbling away on a filthy greasy stove and the stink attacks you. There are tins of cat food and packets of birdseed everywhere and a slice of horsemeat from something that must have been running before the war – the Boer war. The sink is blocked up and you can’t see the pattern on the lino for all the muck that has been trodden into it.

Mrs. Chorlwood picks up a carving knife and for a moment I’m getting ready to bash her over the head if she tries anything.

“Din dins time,” she says with a sigh. “It’s hard work cooking when you have a family my size. Now, don’t open any of the windows whatever you do, we don’t want anyone getting out.”

By this time I’ve got a good idea what I’ve let myself in for, but I don’t know half of it. Mrs. Chorlwood opens the kitchen door and the pong hits me like a kick in the stomach. Cats. Gawd strewth it’s diabolical! The hall and stairs are crawling with bloody cats which make a great rush for us the moment they see Mrs. C. You can’t put your foot down without standing on one of their turds and the carpets are soggy with piss.