Полная версия

The Indoor Artist

Collage is an exciting addition to a watercolour. It produces highly unusual effects, mainly textures, that cannot be achieved any other way. You can add any material to your surface, tissue paper being a favourite of mine. Make an underpainting first, then tear small pieces of tissue (the paper sizes don’t matter, as long as the edges slightly overlap the next piece when stuck down). Stick them to the painting with paper glue. The image will still be visible underneath.

Once the tissue paper has adhered to the surface, paint over it with watercolours (or inks if you prefer). The paint will run beneath the pieces of tissue paper, creating a batik-like effect. When it is dry, the collage can be sealed with a paper varnish. This will tidy any stray pieces of tissue.

With this technique, be prepared not to be in control. The paint will wander wherever it will, but relying on serendipity and being open to adventure is a good thing sometimes when you are painting.

This red pepper was created with torn tissue collage and watercolour. The tissue was stuck in small overlapping pieces onto the paint. More colour was applied on top.

TRYING DIFFERENT TOOLS

The list of tools you can use is endless. There are no right or wrong tools, just some that are better for the job in hand. Of the large number of products on the market, some are useful and others just gimmicks: do you really need to buy a cut-down painting knife for painting stonework when a cut credit card will do just as well? You can use many items found around the home that will create the effects you are seeking and also provide some surprises.

Varying your tools to achieve different effects can be very rewarding. You probably have the usual mop, round brush and small-detail brush for watercolour, but it is good to try some alternatives. I find twigs, credit cards, housepainting brushes, fabric, fingers and fingernails useful, and if you experiment with these you will discover a range of new marks to incorporate in your paintings.

Cut up old credit cards to make painting tools. Here they have been used to make banana palms and foreground grasses.

Twigs make wonderful pens, producing excellent free, characterful marks.

An old household painting brush dipped in watercolour was used to create this ruined church.

Coarse hessian dipped in watercolour made the choppy sea around the rocks.

Fingerprints make good textural marks. Here they were used to describe the baby owl’s fluffy down.

A fingernail scraped through wet watercolour paint made the trunks of these trees.

Silverpoint

Silverpoint was originally used in the 15th and 16th centuries, before the discovery of graphite. It produces very fine detail and makes an interesting change from normal pencil drawing.

It is quite easy to make your own silverpoint. You will need a piece of heavy-duty cartridge paper or watercolour paper; a tube of Chinese White watercolour or white gouache paint; and a silver coin, an item of jewellery, or a piece of silver wire.

Begin by covering the paper completely with a thin coat of white paint. When it is dry, paint again with a thick solution of white (historically, a little colour was sometimes added, which you can achieve by choosing a pigment from your watercolours).

When the second coat of paint is dry, draw into it with your piece of silver. Although the image cannot be rubbed out, moistening the area with a small damp brush will remove unwanted lines.

Silverpoint is particularly good for fine detail work, so 1 used it for this drawing of a little avocet chick to depict its fluffy down coat.

WORKING FROM YOUR PHOTOGRAPHS

Snowy Wood

22 × 29 cm (83/4 × 111/2 in)

For this watercolour painting I used a photograph as reference. I modified the composition and added more colour than the photograph depicted.

Working from photographs is absolutely ideal for the indoor painter. Everything you might ever want to paint is available, from mice to mountains. Make use of your camera when you are out and about, picking subjects you know you will want to paint. Taking pictures of foregrounds, trees, domestic and wild animals, groups of people and skies will soon give you a bulging reference file of your favourite things.

You are not limited to your own pictures, of course – we live in a highly visual age and magazines, newspapers, television programmes, videos and the Internet all present us with dozens of images to inspire us every day.

INTERPRETING PHOTOGRAPHS

Don’t be put off by purists who decry the use of photographs as subject matter. Dégas, Cézanne and Sickert were just three of the many painters who have used photographs as reference, so there is no reason why you should not do so.

However, the purists do have a point. The use of photographs has its pitfalls and you need to be aware of them. Colour and tone can be distorted, as well as shape and size. You must also interpret a photograph as a painting rather than just making a straight copy. Remember always that you are commenting in a pictorial language on what you find beautiful, interesting, dramatic or even horrifying. In the case of shots that have been taken by professional photographers, you also need to make your own interpretation in order to avoid breaking the laws of copyright that protect their images from unauthorized reproduction.

In the photograph on the right the horse’s head appears too large for the body.

To correct the problem, I have drawn the body larger to adjust the scale.

Problems of scale

It is said that the camera cannot lie, but it certainly can. Distortion of size is a common problem. Objects that are nearer the camera can appear much too large and out of scale. Depending upon the lens that the photographer has used, distance can be lengthened or shortened. A long lens, for example, can make a mountain appear to rise directly behind a house when in fact the slopes may be a mile away, while a wide-angle lens will make your garden look twice its length.

Colour and tone

Both colour and tone may be reproduced falsely in a photograph. Many artists work from transparency film because of its greater accuracy in this respect, but it is less forgiving of inaccurate exposure than print film and is thus better avoided unless you are good with a camera. Also, the colour values do vary quite widely between one type of film and another, so if you are taking the photograph yourself, always make colour notes of what you can actually see.

This becomes particularly important in the case of shadows. The lens will see all shadows as black, while the eye is able to discern a range of colours in the dark area. The camera’s problem with reproducing extreme degrees of contrast becomes particularly apparent with a subject such as a sunset. The camera’s light meter reads the scene as one full of light with the result that the darker land below is rendered black in the photograph, though it is seen by the human eye as being softer, more subtle tones of dark grey. Try putting a piece of black paper near the horizon of the next sunset you can view from your window, and you will see what the tones should be.

The photograph of a sunset shows how the horizon is read by the camera as black.

In the painting tones have been corrected to those that the eye can see.

USING BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS

Black and white photographs offer exciting opportunities to the painter. Their tonal range appears wider than colour photographs and therefore more accurate, although the modern black and white photographic print still cannot reproduce the subtleties of tone that can be seen by the human eye.

The most easily accessible source of black and white photographs these days is your daily newspaper. Landscapes and interesting animal studies are of immediate appeal, but your painting does not have to be confined to the beautiful or cute. If you feel strongly about the devastation of war, or the plight of a famine-stricken society, for example, why not say it in a painting? Art is a language as much as is speech. The Spanish painter Goya (1746–1828) painted and etched the horrors of conflict in an effort to express the appalling savagery of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain, while Picasso’s Guernica was his response to the bombing of that town during the Spanish Civil War.

I decided that this black and white photograph of impala would be a good basis for a painting.

Working in colour from black and white

Using black and white photographs for reference does not necessarily mean you have to paint in monochrome; you have exciting creative opportunities here to explore colour themes of your own choice. You will find that the tones in the photograph are easier to see without the confusion of colour distracting your eye, allowing you to establish the tonal balance in your initial composition even before you decide which colours you are going to use. The lack of colour in your reference material will also release you from any preconceived idea of which pigments you should choose and make it a smaller and easier step to depart from a strictly representational approach.

The monochromatic study of the photograph renders good tonal information.

Zimbabwe Impala

15 × 19 cm (6 × 71/2 in)

Here the tonal information has been translated into colour for the finished painting.

Grisaille

A grisaille is a painting executed entirely in a range of tones from black through grey to white. The technique has a long history and was used originally by oil painters to lay in a tonal ground to a painting. John Cozens (1752–97), one of the great English watercolourists, is said to have adapted this method from oil painting and used it in his watercolours.

Grisaille’s great advantage over traditional watercolour method is that the tones are painted first. Colour is then added in washes over the dry tonal ground. Creating tone and colour together is quite a difficult task, and using the grisaille method avoids this problem and is also a fascinating way of working.

You can adapt a grisaille to a watercolour by painting a tonal ground first, using any colour besides black, as long as it is capable of a range of tones from dark to light. If you are wary of the underlying colour being disturbed as you wash more colour on top, try using waterproof ink as your base tonal colour. You can also use acrylic paint to create the base, diluting the colour with water to obtain lighter tones.

This windmill was painted using a grisaille method. I laid in a tonal ground using sepia ink diluted with water to make a range of tones from near black to white. Watercolour was then glazed over the tones to add colour. The left side of the painting below the sky has been left uncoloured to show the tones used.

WORKING FROM TELEVISION

Working from television to improve your drawing skills is enormously useful. A good way to learn to capture movement is by sketching sporting events; try drawing from the next tennis or football match that you watch. Horse racing is another area you might like to explore.

Spend time watching your subject before you draw. See if you can if pinpoint a particular movement you want to catch, then pick up a large sheet of drawing paper and start to draw – fast, as this way you won’t have time to think or become nervous. When the figure changes position, start another drawing. Work on until your sheet is filled with half-finished studies. Eventually a figure will return to the first position you drew, then another, and so on. You should then be able to complete each or most of the studies. Working like this will give you not only practice in capturing movement but also studies of figures that can be used later in a painting.

I had a lot of fun drawing a sumo wrestling match on television. The two giant figures were a fantastic mass of curves and folds as they struggled with each other.

Working from a video

Working from a video is even more useful, since you can ‘freeze’ movement in order to study and draw it. You can even draw over the forms on the screen with tracing paper. I did this once when I needed reference for a coach and horses for a book I was illustrating.

These sketches were made from a televised horse show.

There are many videos available on the subject of wildlife. Use them to further your knowledge of animal anatomy and as direct reference sources for paintings. The Internet is also a good source of reference for almost anything you need.

I adapted one of my sketches into a composition using gouache and watercolour, incorporating a background from another source.

I made several sketches from a video about bears with the idea of using them for a painting.

PROJECT

PAINT A PICTURE FROM A VIDEO

LOOKING AT SHAPE AND FORM

Middle East Street

20 × 30 cm (8 × 12 in)

The strong sunlight of this Middle Eastern scene causes dark shadows which help to link the composition together.

The three-dimensional form that makes a painting convincing is created by light and shadow, depicted as tone and colour. Simplifying objects to geometrical shapes and studying the way the light falls upon them will help you to render their structure and volume, while varying the source and strength of lighting in a painting will create very different atmospheres and moods.

Shadows are a vital part of picture-making, and they don’t have to be grey. Awareness of the colour in shadows is important, and easy once you understand some simple colour theory. Equally important is considering the shapes between the objects, which play just as large a role in the composition as the objects themselves.

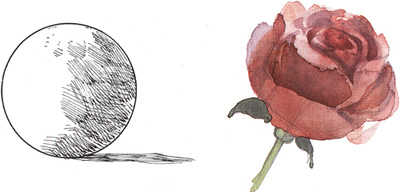

UNDERSTANDING FORM

By simplifying objects to basic geometric shapes you can more easily observe the effects of light and shadow that describe the volume of their form. Almost anything can be reduced to a sphere, a cone, a cylinder or a cube. Once you look for these elemental shapes, you will be able to tackle even the most complicated forms with confidence.

Using shapes together

Once you have accustomed yourself to seeing objects as geometric shapes, you can easily add them together. Try reducing a tree to a simple sphere sitting on a tube, for example; this is the basic structure and volume of most trees, especially when they are in full leaf. Simplifying the form will help you to realize the volume a tree possesses. Within its outer spherical shape are numbers of smaller round shapes, which become the foliage masses. Shapes will obviously vary with the type of tree, but if you are aware of this basic underlying form it will help you paint trees and foliage more successfully.

A sphere: a rose

A cone: a seated dog

A cube: a house

A cylinder: a bottle

These elemental forms will help you construct more complicated drawings.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.