Полная версия

The Vietnam War: History in an Hour

THE VIETNAM WAR

History in an Hour

Neil Smith

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Visit the History in an Hour website:

www.historyinanhour.com

First published by HarperPress in 2012

Copyright © Neil Smith 2012

Series editor: Rupert Colley

IN AN HOUR ® is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers Limited

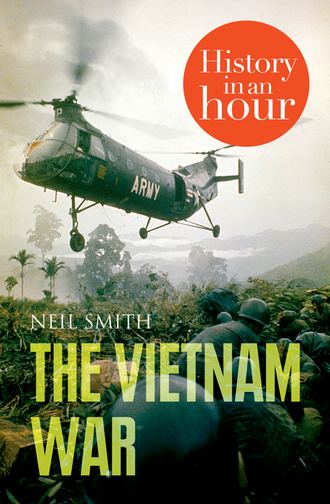

Cover image © Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

The moral right of the author is asserted

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights resevred under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © MAY 2013 ISBN: 9780007485178

Version: 2017-03-08

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further. Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn . . .

To find out more visit www.historyinanhour.com or follow us on twitter: twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents

Cover

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

The First Indochina War and the End of French Rule

Eisenhower and Vietnam

Building South Vietnam, 1954–63

JFK and US Escalation

Lyndon Johnson: From Assassination to Americanization

The Tet Offensive

Nixon: Peace with Honour?

US Military Strategy

Domestic Opposition to the War

North Vietnam and the Viet Cong

Appendix 1: Key Players

Appendix 2: Timeline of the Vietnam War

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

The Vietnam War was the most traumatic military experience which the United States has been involved in – in spite of the ongoing engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq. Vietnam was a conflict which cost the US almost 60,000 lives and destroyed two presidencies. It provoked such unrest at home that anti-war protestors were killed on university campuses, and Congress was forced to limit the executive branch from taking future military action without approval from the legislature. The impact on South East Asia was even greater. While the actual number of Vietnamese deaths is disputed, up to four million Vietnamese died during the conflict, and the resulting political and military upheaval triggered communist revolutions in Laos and Cambodia. Thailand, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand all provided troops to support the US war effort.

Vietnam is a narrow, ‘S-shaped’ country running for 2,000 km between China and the Gulf of Tonkin in the north, to the South China Sea in the south; Laos and Cambodia lie to the west. Most of Vietnam is mountainous, with a long chain of forested mountains running down the centre and western side. Large areas of flat and fertile land lies in the south, centred around the capital city Hanoi and in the Mekong Delta in the south. The latter is the food bowl of the nation, producing three rice crops a year.

Map of Vietnam

US National Archives and Records Administration, (NARA)

French Indochina was formed initially from modern-day Vietnam and Cambodia; Laos was added in 1893. Life under French rule was largely grim, with brutal treatment meted out to any groups attempting to assert Vietnamese independence, and an eclectic range of opposition groups emerged. The Vietnamese Communist Party was formed in February 1930, and although it had suffered periods of repression and exile, by the start of the Second World War, it had assumed a place at the forefront of resistance to Imperial rule in Indochina.

During the Second World War, the country was occupied by the Japanese. They allowed the French to maintain control of their colony, thus inflicting what the nationalist Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh later described as a double yoke of Imperialism on the people. At the end of the war, Ho Chi Minh declared the creation of an independent Vietnamese state; something which the French, with British and US support would not tolerate. Between 1946–54 the First Indochina War was fought between Ho’s ‘Viet Minh’ (League for the Independence of Vietnam) and the French. After the French defeat at Dien bien phu in 1954, the country was partitioned and an anti-communist State was formed in the south. Propped up by the US, whose involvement grew steadily during 1954–65, to the point where it assumed responsibility for the war against the communist insurgents. In spite of an immense military campaign, the US withdrew its forces from Vietnam in 1973, having failed to defeat the Communists, and having failed to create a strong, stable State in the South. Within two years, Vietnam would be once again unified, but under the control of Hanoi.

This, in an hour, is the history of the Vietnam War.

The First Indochina War and the End of French Rule

On 2 September 1945, Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Indochina Communist Party, and effective leader of the revolt against the Japanese invaders, declared Vietnamese independence in Saigon. Although this ceremony was witnessed by several US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents sent to coordinate opposition to the Japanese, the French were quick to reclaim their former grip on their colonies in Indochina. Within a month of Ho’s proclamation, they had initiated a military campaign against the Viet Minh, with the primary intention of re-establishing their influence in the country.

From the start of 1946 until the outbreak of the First Indochina War in December 1946, both sides demonstrated a willingness to negotiate, while pursuing low-level military action against the other. By 6 March 1946, a preliminary agreement had been reached recognizing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) as a Free State within the French Union, with referendums over the future of the provinces of Cochinchina, Annam and Tonkin to follow. Unfortunately, neither French officials in Vietnam, nor Ho’s supporters were satisfied with the agreement, and both groups seemed content to see the situation drift towards civil war.

The trigger for war came in late November 1946 when the French commander in Indochina, General Jean-Etienne Valluy, authorized the bombardment of the Vietnamese settlement in Haiphong, resulting in approximately 6,000 Vietnamese fatalities. On 19 December, French forces in Hanoi demanded that the occupants of the city surrender their weapons. Authorized to do so by the party leadership, General Giap, Minister of the Interior in the DRV, refused and declared the start of a war of resistance against the French colonialists.

Letter from Ho Chi Minh to President Harry S. Truman, 28 February 1946

NARA

In response to the overwhelming advantage held by the French in terms of weaponry and manpower, the Viet Minh fled to the countryside. Their determination and willingness to absorb huge casualties shocked the French forces, who expected an easy victory. Ho’s adoption of a guerrilla ‘hit and run’ strategy proved effective in the early stages of the war in denying the countryside to the French, which in turn provided a greater opportunity for Ho to wage a political war targeted at the Vietnamese peasantry.

For the US this situation presented a dilemma. The classic Wilsonian liberalism which had underpinned the US approach to both World Wars was resolutely anti-colonialist; indeed the copy of the Declaration of Independence quoted extensively in Ho’s declaration of the Republic of Vietnam in September 1945 was actually provided by US agents. Ho appealed to this strand of liberalism in the months after the end of the war, sending a series of messages to Washington asking for help. None of these were replied to.

The wider context of the Cold War in Europe and Asia, along with suspicions over Ho’s ideological leanings, persuaded both President Truman and Eisenhower that they should not accede to his requests for support. The US did not want to antagonize the French, especially after the creation of NATO in 1949 and the ongoing concern over Germany’s future. Furthermore, the fear of the spread of Communism into Asia from China (communist since 1949) and the start of the Korean War in June 1950, forced the hand of the US. Many in Washington were highly sceptical about Ho’s claims to be a mere nationalist. Indeed, the prevailing view was that nationalism proved to be a convenient fig leaf for all communists to hide behind, in their battles against Western colonial rulers: once the Imperialists had been removed, so the true colours of the guerrillas would appear. In a telegram (20 May 1949) to the US Consulate in Hanoi, US Secretary of State, Dean Acheson summed up this position perfectly in 1949, stating ‘all Stalinists in colonial areas are nationalists.’

In an attempt to counter the Viet Minh’s appeal to Vietnamese nationalists, and to solidify US support, the French introduced a new government in March 1949. It was headed by former Emperor Bao Dai, and had the power to manage its own foreign affairs and establish a Vietnamese army. While the Emperor proved to be an unconvincing advertisement for ‘third force’ politics in Indochina, the outbreak of the Korean War had a significant impact on US attitudes to the communist threat in Asia. As a result of the North Korean invasion over the 38th parallel, US aid increased considerably, to the point it was funding 80 per cent of the French war effort against the Viet Minh. In addition, US involvement in Vietnam started with the creation of the Military Assistance and Advisory Group, Vietnam in September 1950.

Militarily, however, the French lack of manpower in Vietnam restricted their ability to launch the concerted offensives required to capture and hold territory throughout the country. By the middle of 1953, the Viet Minh were approximately 60 per cent strength of the French, but were able to launch more frequent attacks against a foe increasingly committed to defence, and looking for a way to end the conflict. This was the context in which General Henri Navarre developed a plan to lure the Viet Minh into a conventional battle, where he would achieve the decisive victory of the war. He established a strongpoint at Dien bien phu, a remote outpost in the north of the country, chosen so as to prevent Viet Minh infiltration into neighbouring Laos. Its airfield also meant that the garrison could be easily re-supplied by air. Unbeknown to Navarre, Giap had managed to surround the 13,000 troops at the French base with 50,000 men, and co-ordinated the immense physical task of hauling heavy artillery up the mountains surrounding the French position.

The Battle of Dien bien phu started on 13 March 1954. In spite of French diplomatic pressure, the US refused to intervene with airstrikes against the Viet Minh positions, but they did provide ammunitions and material support to the French, in accordance the Mutual Defence Assistance Act. When the battle ended on 7 May, the French casualties were enormous: they suffered almost 3,000 killed, with 10,000 taken prisoner. The DRV gained fresh impetus in the ongoing Geneva peace talks, while the French had to accept that their role in Vietnam’s future was about to come to a swift and ignominious end.

Eisenhower and Vietnam

When Dwight Eisenhower assumed responsibility for the US commitment to the French cause in South East Asia, their contribution was approximately 40 per cent of the French war effort. By the time he left the White House, the US was upholding an independent South Vietnam, and providing over 700 advisors to the South Vietnamese Army. During his time in office, the US had assumed sole responsibility for the future of South Vietnam, and involved itself to an extent that withdrawal was not an option for his successors as President.

Eisenhower’s attitude to South East Asia was heavily influenced by the context of the Cold War. In particular, the communist victory in China in 1949, the subsequent North Korean invasion of South Korea in 1950, and the British struggle with communist rebels in Malaya. A 1950 National Security Council report NSC–68, warned that Communism had become a global, rather than purely European, threat.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles (from left) greet South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem at Washington National Airport, 8 May 1957

NARA

Accordingly, he described the nature of the threat posed in South East Asia in terms which would provide shorthand for US concerns for the next nineteen years. While not using the phrase himself, his description of the ’domino theory’ in a press conference on 7 April 1954, outlined the consequences for neighbouring countries if a communist State emerged in Vietnam after the French withdrawal. Eisenhower’s first major test in Indochina came in March 1954, with the impending French defeat at Dien bien phu. He had previously been critical of the French strategy in the months preceding the battle and believed that General Navarre’s plan to fight the decisive battle of the war in such difficult terrain seriously undermined any chance of a successful outcome. As the battle progressed, he was under pressure from the French and members of his own party to intervene with US airpower, in order to prevent both French defeat on the battlefield, which might then lead to the fall of South East Asia to Communism, and subsequent capitulation in the Geneva negotiations.

The President adopted a middle path designed to put off immediate US military intervention while at the same time placing this possibility in the public domain. His four preconditions for intervention were: clear objectives had to be met; intervention had to be restricted to air and sea; Congress had to support action; and France had to agree to full independence for Vietnam. Lacking Congressional support, Eisenhower kept US forces out of the battle.

The resulting Geneva peace conference temporarily divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel. The Viet Minh were given control of North Vietnam, while a capitalist state was created in the South. Formal unification elections were scheduled to take place in 1956. The response from the US was mixed. On the one hand, it represented the first time land had been voluntarily ceded to Communism; it allowed the US to develop South Vietnam into a shining example of a non-communist and non-colonial state in South East Asia; the two year period until unification elections would provide sufficient time to develop the vote and build support for the Diem regime.

After the division of Vietnam, the US took responsibility for South Vietnam from the French, and set itself the goal of making the country politically stable, economically self-sufficient, capable of providing for its own internal security, and dealing with an invasion from North Vietnam. To achieve these goals, it implemented a three-pronged strategy. Firstly, it established the South East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO), a regional defence grouping consisting of the US, Great Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, Philippines, and Pakistan. Although SEATO’s focus was on protecting a very wide area across South East Asia, the Treaty’s protocol identified Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnam as areas of possible conflict, and that member states would ‘act to meet the common danger’ should these territories be threatened.

The second element of the strategy was targeted at the communist State above the 17th parallel, and was based on CIA subversion. Colonel Edward Lansdale, based in Saigon, controlled all efforts to undermine the Hanoi Government. The tactics deployed to achieve this goal were largely based around a campaign of psychological warfare against the North. This included such diverse actions as emptying sand into the petrol tanks of buses, bombarding the northern population with pornographic images (intended to entice them to support the South) and fake astrological charts predicting a troubled future for the North.

The third and most important strand of the US campaign in the regions, was the ‘nation-building’ project in South Vietnam. Between 1955–60, the US provided nearly $7 billion in aid, making South Vietnam the fifth largest recipient of US aid in the world. In spite of repeated warnings, Prime Minister Diem ignored demands to broaden his power base by cultivating popular support. Instead, he maintained a repressive regime, knowing that US fears about communist expansion in the region, heavily outweighed any other fears they may have had about the nature of the regime operating in the South.

In order to develop the military capabilities of South Vietnam, the US created the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), and despatched 750 advisors to train it in counter-subversion techniques. However, while they were giving Diem the means to create what was in effect a dictatorship, the US ignored the concerns of ordinary South Vietnamese villagers, who blamed Diem’s corrupt regime for denying them land ownership and poor living standards.

Placing the future of Indochina into the context of the wider Cold War, Eisenhower arguably committed future US Presidents to maintaining the security of an anti-communist State in the South. Furthermore, he had authorized a repressive, military-based approach to tackling the communist threat in the region at the expense of building a popular, democratic government. These measures therefore created a ‘quagmire’ which US was neither able to extricate herself from nor make any effective progress with. While Eisenhower had not committed any troops or bombers to the area, he left a commitment which became inextricably linked to US credibility in the Cold War, yet offered little hope of long-term success in its war against Communism.

Building South Vietnam, 1954–63

The aftermath of the Geneva peace conference saw Ngo Dinh Diem appointed Prime Minister by Head of State, Bao Dai, and one million refugees flee south from above the parallel. With Vietnam partitioned at the 17th parallel, US settled on a policy of turning the southern State into a permanent bulwark against the rising tide of Asiatic communism, with Diem at the helm.

However, several obstacles were in the way of achieving this goal. For a start, Diem faced opposition from Bao Dai who gave Diem little authority, and only used him as a source of income from the US, and the main South Vietnamese sects: Binh Xuyen, a large militia with strong links to the criminal underworld; the Cao Dai; and the Hoa Hao. External powers also posed potential problems for Diem, with the French retaining 160,000 troops in the country, and a large concentration of communist agitators remaining around the Mekong Delta. Furthermore, the Geneva Accords included an agreement to hold a unification election in 1956. Using a combination of bribery, CIA counter-insurgency, and brute force, Diem was able to subdue the sect’s rebellion by June 1955. By October 1955, Diem annihilated Bao Dai in a rigged referendum (Diem won 98.2 per cent of the vote) over who should run the country, and transformed the monarchy into the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). As a result of concerted US pressure, the French were finally persuaded to leave Vietnam by April 1956. Regarding the unification elections, neither Diem nor his US supporters showed any willingness to participate. The US pointed to a legal technicality in that they had not signed the Accords, therefore were not bound by them, and suggested that as the North was effectively a one-party communist State, the elections there would, in no sense, be free.

Vietnamese Air Force pledging its support for President Ngo Dinh Diem after a political uprising, Saigon, South Vietnam, March 1962

NARA

Diem’s regime was not based on popular consent, nor did it aspire to win the support of the Vietnamese people. The government was dominated by Catholics, in a country where only 10 per cent were of a similar faith, and the major offices of State were placed in the hands of Diem’s own family. His youngest brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, held a variety of powerful positions: Minister of the Interior, Diem’s main advisor, and chief of the Can Lao secret police. Another brother, Ngo Dinh Thuc was also appointed the Catholic archbishop of Hue. The regime was the embodiment of political corruption, and consequently there was no meaningful attempt to introduce political, economic or social reforms. The US response was to ignore Diem’s failure to establish a mandated government in the South, while sending clear signals that he was on the right track.

Eisenhower’s government provided military aid at a ratio of 4:1 to that of general economic aid. In all public meetings with Diem, successive US politicians praised him and held him up as a bastion of anti-Communism. Diem’s 1957 visit to the US saw him extolled by President Eisenhower for his ‘heroism and statesmanship’, while he was given a ticker tape parade through New York. Four years later, Vice President Johnson hailed Diem as the ‘Churchill of Asia’. The main reason why the US chose to tolerate a dictator who appeared, in the longer term, to be harmful to their chances of building a stable republic below the 17th parallel is that, above all else, Diem’s credentials as an anti-communist were impeccable. He had made a name for himself as a hard-line opponent while serving as governor in Binh Thuan Province during the 1920s and early 30s. As leader of the RVN he instigated a brutal campaign against suspected and actual communists. Over 50,000 political opponents were sent to labour camps, and 12,000 executed during 1955–59, with a further 2,000 killed by the ARVN during the small uprising in 1957. The impact on the southern Communists was severe: of the 10,000 or so members of the Vietnam Workers Party who remained in the South after partition, an estimated 5,000 remained by 1959. However, the effect on the population at large was to further alienate Diem from the people.