Полная версия

China

That Confucius was a formidable scholar and an inspirational mentor with a well-defined mission is more relevant. In a thumbnail autobiography, his professional aspirations receive not a mention:

At fifteen my heart was set upon learning; at forty I was no longer perplexed; at fifty I understood Heaven’s Decree; at sixty I was attuned to wisdom; at seventy I could follow my heart’s desires without overstepping the mark.21

Like Socrates, who was born just a decade after Confucius’s death, he believed that morality and virtue would triumph if only men would study. Take a town of 10,000 households, he told his followers. It would surely contain many who were as loyal and trustworthy as he, but there would be none who cared as much about learning as he. In the course of his intellectual odyssey, he may actually have written the short ‘Spring and Autumn’ Annals (Chunqiu) – he was certainly familiar with them – and he may have contributed to the compilation of other works such as ‘The Book of Songs’ (Shijing), a particular favourite. But the authorship of all such texts is problematic; their compilation in the forms that survive today resulted from several ‘layers’ of scholarship, not to mention dollops of blatant fabrication, spread over many centuries.

The same is true of parts of his collected sayings, known as The Analects (Lunyu), and from which the quotations above are taken. But it is thought that other parts genuinely represent what the Master said in conversation with his disciples. They thus have an identity and an immediacy that are more akin to those of the Gospels than, say, the jataka stories on which the Buddha’s life is based. Here then is what Laozi might have called a proper ‘shoe’, not just ‘a footprint’, a recognisable voice, the first in China’s history and arguably the greatest, addressing and exhorting the listener directly. Sometimes combative like an out-of-sorts Dr Johnson, the Master belies his dry-as-dust reputation, endearing himself to the reader much as he did to his disciples.

Confucius himself always disclaimed originality. Although there is little consensus about many of his key concepts – and even less about which English words best represent them – the gist of his teaching seems not especially controversial. Sons must honour their fathers, wives their husbands, younger brothers their elder brothers, subjects their rulers. ‘Gentlemen’ should be loyal, truthful, careful in speech and above all ‘humane’ in the sense of treating others as they would expect to be treated themselves. Rulers, while enjoying the confidence of the people and ensuring that they are fed and safe, should be attuned to Heaven’s Mandate and as aloof and constant as the northern star. Laws and punishments invite only evasion; better to rule by moral example and exemplary observance of the rites; the people will then be shamed into correcting themselves. Self-cultivation, or self-correction (a forebear of Maoist ‘self-criticism’), is the key to virtue. Of death and the afterlife, let alone ‘portents, prodigies, disorders and deities’, Confucius has nothing to say. It is up to the individual, assisted by his teacher, to cultivate himself. Not even he was born with knowledge; he is just ‘someone who loves the past and is diligent in seeking it’.22

‘I transmit but do not innovate. I am truthful in what I say and devoted to antiquity.’23 For Confucius, ‘the Way’ was the way of the past and his job was that of transmitting it or conveying it. The mythical Five Emperors, the Xia, the Shang and above all the Zhou – these were the models to which society must return if order was to be restored. ‘I am for the Zhou,’ he declared, meaning not the hapless incumbent in Luoyang but Kings Wu, Wen, Cheng and Kang of the early (Western) Zhou and of course the admirable Duke of Zhou. The rites of personal conduct and public sacrifice must be observed scrupulously; more important, they must, as of old, be observed sincerely. The ‘rectification of names’, a quintessentially Confucian doctrine, was a plea not for the redefinition of key titles and concepts in the light of modern usage but for the revival of the true meaning and significance that originally attached to them. More a legitimist than a conservative, Confucius elevated the past, or his interpretation of it, into a moral imperative for the present.

And there it would stay for two and half millennia. It was as if history, like Heaven, brandished a ‘mandate’ that no ruler could afford to ignore. But this general principle soon came to transcend the particular injunctions contained in the few, if pithy, soundbites of The Analects. Aboard the Master’s ‘conveyance’, and labelled as ‘Confucianist’ (rather than ‘Confucian’), then ‘Neo-Confucianist’, would be loaded all manner of doubtful merchandise. History would prove more tractable than Heaven.

WARRING STATES AND STATIST WARS

By the time Confucius died in 479 BC, the ‘Spring and Autumn’ period was fast fading into the crisis-ridden ‘Warring States’ period. Already the large state of Jin, once ruled by Chonger, was disintegrating. Not until the end of the century would it be consolidated into the three states of Han, Zhao and Wei (not to be confused with the river of that name), so presenting the Zhou king in Luoyang, their supposed superior, with an unwelcome fait accompli. When he did reluctantly accept it, it is said that the bronze cauldrons of Zhou, symbols of the ancient dynasty’s virtue, ‘shook’. Also shaken, in fact toppled, within a century of Confucius’s death was the ruling house of Qi, the largest state in Shandong. In a fin de siècle atmosphere ‘all now took it for granted that eventually the now purely nominal Zhou dynasty would inevitably be replaced by a new world power’.24

The ferocious fight to the death among the strongest of the remaining states makes for grim telling. Standing armies take the field for the first time, new methods of warfare swell the casualties, and statecraft becomes more ruthless. Yet the period is by no means devoid of other arts. Stimulated by the disciples and heirs of Confucius, China’s great tradition of philosophical speculation was born. It was an era, too, of startling artistic creation in which traditional arts began to break free from the constraints of ritual. And from the recent excavation of a host of contemporary texts it appears to have been an important age for medicine, natural philosophy and the occult sciences. Far from being a cultural cesspool, the ‘Warring States’ period, like other interludes of political instability, sparkles with intellectual activity and artistic mastery.

Of all the tombs excavated in the late twentieth century, perhaps the most surprising were those opened in 1978 and 1981 at Leigudun near the city of Suizhou in Hubei province. South of the arena in which the ‘central states’ competed and nearer the Yangzi than the Yellow River, Leigudun was the capital of a mini-state called Zeng. During the ‘Spring and Autumn’ period Zeng had been subordinated by Chu, the great southern power that had once contended with the early (Western) Zhou and later with Chonger of Jin.

Although Zeng’s rulers had retained the rank of ‘marquis’, the minor status of their beleaguered marquisate promised the archaeologists nothing special in the way of grave goods. It was pure luck that one of the tombs proved to be that of the ruler himself, Zeng Hou Yi (‘Marquis Yi of Zeng’), who died about 433 BC. Even foreknowledge of this elite presence would hardly have prepared the diggers for the staggering array of exquisite jades, naturalistic lacquerware and monumental bronzes that were laboriously brought to the surface. Now occupying half of a palatial museum in the provincial capital of Wuchang (part of the three-city Wuhan complex), the contents of the Zeng Hou Yi tomb have been described by Li Ling, director of the ‘Mass Work Department’ responsible for the excavation, as an exceptional discovery ‘that shocked the country and the world as well’.25

Leigudun’s 114 bronzes weigh in at over ten tonnes, yet they ‘shock’ more by reason of the lacy profusion of their openwork decoration. Squirming with snakes, dripping with dragons and prickly with other sculptural protuberances, their shapes are further obscured by a fretwork of the wormy encrustation known as vermiculation. They look as if they have lain for two and a half millennia not in the ground but on the seabed and been colonised by crustacea. For this triumph of flamboyance over form – and of the lost-wax process over in-mould casting – one should not fault the marquis’s taste. Sites elsewhere in Chu territory have yielded items nearly as extravagant. But at Leigudun ornamentation was taken about as far as metal-melting would permit. Chu’s connoisseurs of the fanciful and intricate were already turning to lacquerware, inlay and fine silks. As the storm clouds gathered over the zhongguo, the courts and artisans of this south-central state would establish a tradition of cultural exuberance and eccentric exoticism that, in the plaintive Songs of Chu (Chuci), would long survive the political extinction of ‘great Chu’.

The centrepiece of the Leigudun collection is a house-size musical ensemble consisting of sixty-five bronze bells with a combined weight of 2,500 kilograms (5,500 pounds). The bells are clapper-less (they were struck with wooden mallets), arranged according to size, and suspended in three tiers from a massive and highly ornate timber frame, part-lacquered in red and black. In an unusual but highly successful foray into figurative sculpture, bronze caryatids with swords in their belts and arms aloft stand braced to support each tier. At the centre of the ensemble the largest bell is a replacement. Its design is more elaborate than the others and it carries a dedicatory inscription to the effect that King Hui of Chu, hearing of the death of Marquis Yi of Zeng, had had this bell specially cast and sent it as an offering to be employed in the marquis’s mortuary rites.

Significantly, the Chu ruler is here described as wang, that is ‘king’, a title still reserved to the fading Zhou, not adopted by other warring states until the late fourth century BC, but in use in Chu since at least the tenth century BC. Chu was evidently in a league apart from the ‘central states’, although its political trajectory is far from clear. Originating somewhere in southern Henan or northern Hubei, it had slowly spread to embrace an enormous arc through what is now central China from the Huai River basin to the Yangzi gorges and Sichuan. Expansion was largely at the cost of non-Xia peoples, referred to as Man, whose traditions no doubt account for Chu’s distinctive cultural profile and whose incorporation may explain why the ‘central states’ disparaged Chu as non-Xia and so ‘not one of us’.

Southward expansion had brought Chu into contact with other culturally hybrid polities outside the ‘central states’. In effect the zhongguo ‘cradle’ of Chinese civilisation in the north was already being challenged by the states of ‘core’ China farther south. They included Wu in the region of the Yangzi delta in Zhejiang, and Yue to the south of Wu in Fujian, with both of whom Chu was occasionally at war. In the late sixth century BC, Wu had overrun Chu and obliged its king to flee to Zeng, where the then marquis had given him protection. Frustrated by this grant of sanctuary, the Wu ruler had vented his fury on an earlier Chu king, whose corpse, or what remained of it, was exhumed, publicly flogged and thoroughly dismembered. Wu’s ruler was made ba (‘hegemon’) in 482 BC but nine years later was conquered by Yue. Chu thereupon retook most of its lost territory; and it is supposed that it was in remembrance of Zeng’s act of mercy to his fugitive predecessor that in 433 BC King Hui of Chu caused the great central bell of the Leigudun ensemble to be cast for the tomb of Marquis Yi, the grandson of Chu’s saviour.

States like Chu, Wu and Yue that were located around or beyond the perimeter of the northern ‘central plain’ figure prominently from the fifth century BC onwards. Their consolidation may have benefited from immigration as refugees fled from the fighting in the north, and they certainly took advantage of a wave of centralising reforms that significantly advanced state formation throughout China in the sixth to fourth centuries BC. Cause and effect are hard to distinguish in this process. To adapt a formulation used in respect of the European states in the later Middle Ages, during the ‘Warring States’ period ‘the state made war and war made the state’.26 Although in China the state proved a better warmonger than war did a state-monger – for the wars got worse and the states got fewer – the military imperative of mobilising all possible resources clearly depended on civil reforms that strengthened the authority of the state.

Qi in Shandong had pioneered the process and most other states followed suit, the last and most thoroughgoing reforms being those in Qin. Essentially the reforms reversed the earlier trend towards feudal fragmentation. Borderlands and newly conquered or reconquered territories, instead of being granted out as fiefs, were formed into administrative ‘counties’ or ‘commanderies’ under centrally appointed ministers and could thus serve as recruitment units. This system was then extended to the rest of the state; population registration and the introduction of a capitation tax would soon follow. Meanwhile oaths, sealed in blood, were sworn to secure the loyalty of subordinate lineages, while rival lineages might be officially proscribed. Regulations and laws were standardised and then ‘published’ in bronze inscriptions. Land was gradually re-allocated in return for a tax on its yield, the tax being increasingly paid in coin.

Histories, such as the Zhanguoce and the later Shiji, tend to deal with such developments in terms of personnel rather than policy. Reforms receive mention when they can be credited to a minister or adviser deemed worthy of his own biographical sketch. Viewed thus, the rivalry between the warring states includes an important element of competitive headhunting. Attracting the loftiest minds, the most ingenious strategists and the most feared generals not only improved a ruler’s chances of victory but advertised his virtuous credentials (for virtue attracted expertise like a magnet) and so advanced his candidacy for the award of Heaven’s Mandate.

Job-hunting shi in general rejoiced; and especially favoured were those savants who, while extending or rejecting the teachings of Confucius, propounded theories about authority and human motivation that included good practical insights into some aspect of statecraft or man-management. Mozi (‘Master Mo’, c. 480–c. 390 BC, but known only for his eponymous text), after advocating a more frugal, caring and pacific society, appended some twenty chapters on defensive tactics, they being the only kind of military activity in which a peace-loving disciple of Mozi (or a Mohist) might decently engage. Unconventional and idealistic, Mohism seems to have been most influential in the ever-eccentric Chu.

Mengzi lived about fifty years later and found employment at the court of Wei, but he too is otherwise an obscure figure. Devoted to the memory of Confucius, he fleshed out the Master’s utterances into a detailed programme for reform: emulate the mythical Five Emperors and the Three Dynasties (Xia, Shang and Zhou), urged Mengzi; respect Heaven’s Mandate, reduce punishments and taxes, and reinstate the ‘well-field’ system of landholding; in an age of greed and violence only a ruler who abjured oppression, who cultivated virtue and consulted the welfare of the people, would be sure to triumph; likewise for society as a whole – morality would prevail if human nature was allowed to realise its basic goodness. All of which, while reassuring, made little impression on zhongguo’s power-crazed warlords. Only later would it win for Mengzi the title of ‘second sage’ in the great Confucian tradition and later still the Latinisation of his name into ‘Mencius’ by Rome’s almost-approving missionaries.

Of far more influence, and decisive for the triumph of centralised government in the state of Qin, was a school of thought known as ‘legalism’. Later histories credit, or more usually condemn, one Shang Yang, minister of Qin from 356 BC, for erecting the draconian framework of the first ‘legalist’ state, although it would be left to others to provide a theoretical basis for it. Like Chu in the south, Qin in the far north-west was peripheral to the ‘central states’ and was habitually disparaged by them as non-Xia. It had expanded into the valley of the River Wei, once the Western Zhou heartland, but its roots lay farther west and its population included large numbers of pastoral Rong. Problems of integration and defence kept Qin on the sidelines until Shang Yang, after learning his trade in Wei state, interested Qin’s duke in a programme of radical restructuring. The ‘county’ system of direct administration was introduced, weights and measures standardised, trade heavily taxed, agriculture encouraged with irrigation and colonisation schemes, and the entire population registered, individually taxed and universally conscripted. ‘Mobilising the masses’ was not a twentieth-century innovation.

The carrot in all this was an elaborate system of rankings, each with privileges and emoluments, by which the individual might advance according to a fixed tariff; in battle, for instance, decapitating one of the enemy brought automatic promotion by one rank. But more effective than the carrot was the stick, which took the form of a legal code enjoining ferocious and indiscriminate punishments for even minor derelictions. Households were grouped together in fives or tens, each group being mutually responsible for reporting any indiscretion by its members; failing an informant, the whole group was mutually liable for the prescribed punishment. In battle this translated into a punitive esprit de corps. Serving members of the same household group were expected to arrest any comrade who fled, to deliver a fixed quota of enemy heads, and to suffer collective punishment if they failed on either count. Shang Yang was himself a capable general and may have led some of these conscript units (or perhaps ‘neighbourhood militias’) when Qin forces scored a decisive victory over the state of Wei in 341 BC. Sixteen years later Qin’s duke assumed the title of ‘king’. But by then Shang Yang, following the death of his patron, had fallen foul of his own penal code and been condemned to an ignominious extinction, being ‘torn apart by carriages’.27

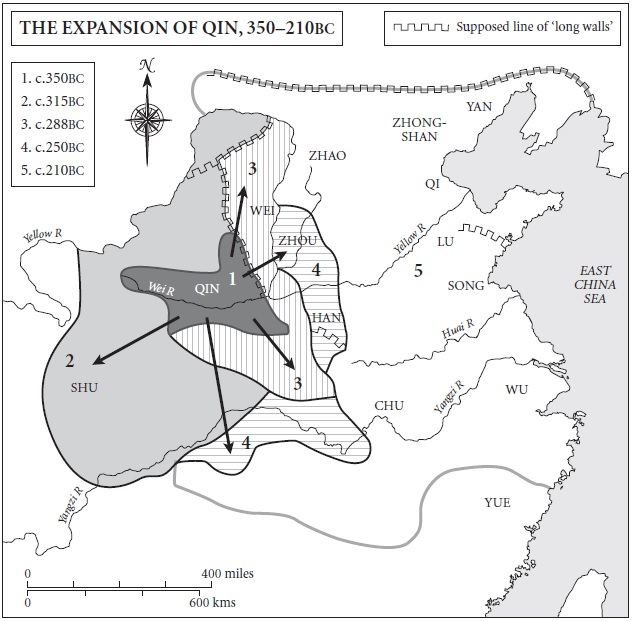

In practice it may have been that not all these measures were Shang Yang’s. Some may have been awarded him posthumously by the backdating beloved of historians. And they may not have been as harsh as they are portrayed; discrediting Qin and its policies would be a priority of the subsequent Han dynasty, during whose long ascendancy Qin’s history would be compiled. The reforms were nevertheless sensationally effective. Besides again ravaging Wei state, in 316 BC Qin’s forces swept south over the Qinling mountains into Sichuan and thus, as will be seen, secured a vast new source of cereals and manpower plus some important strategic leverage over Chu. During the last century of the ‘Warring States’ (c. 320–220 BC) Qin was more than a match for any of its rivals. It largely dictated the ever shifting pattern of alliances and it initiated about forty of the sixty ‘great power wars’ recorded for the period.

Visiting Xianyang, Qin’s new capital, in c. 263 BC the philosopher Xunzi was both impressed and appalled – impressed by the decorum and the quiet sense of purpose, appalled by the lack of scholarship and the plight of the people; they were ‘terrorised by authority, embittered by hardship, cajoled by rewards and cowed by punishments’. In fact the whole state seemed to be ‘living in constant terror and apprehension lest the rest of the world should someday unite and strike it down’.28 Xunzi wanted nothing to do with the place, and having previously directed the Jixia, an intellectual academy in the state of Qi, he hastened on to a more congenial post in Zhao, then one in Chu, so completing a circuit of four of the main power contenders. It was deeply ironic that it would be Han Fei, one of Xunzi’s disciples, who would eventually provide legalism with an intellectually respectable rationale, and another, Li Si, who as the First Emperor’s chief minister would become legalism’s most notorious practitioner.

At about the same time as Xunzi’s visit to Xianyang, Qin abandoned the traditional policy of alliances and adopted one of unilateral expansion through naked aggression. ‘Attack not only their territory but also their people,’ advised Qin’s then chief minister, for as Xunzi had put it, ‘the ruler is just the boat but the people are the water’. Enemy forces must be not only defeated but annihilated so that their state lost the capacity to fight back. ‘Here’, intones the Cambridge History of Ancient China, ‘we find enunciated as policy the mass slaughters of the third century BC.’

The slaughters were made more feasible by important advances in weaponry and military organisation. In the ‘Spring and Autumn’ period, military capacity had been assessed in terms of horse-drawn chariots. Besides usually three passengers – commander, archer/bodyguard and charioteer – each of the two-wheeled chariots was accompanied by a complement of about seventy infantrymen armed with lances, who ran alongside and did most of the fighting. The chariot was a speedy prestige conveyance for ‘feudal’ lords and provided a vantage and rallying point for the troops, but it often got stuck in the mud and was liable to overturn on rough terrain.

As centralisation increasingly relieved subordinate lineages of their fiefs and autonomy, most states supplemented these ‘feudal’ levies of chariots and runners by recruiting bodies of professional infantrymen that rapidly grew into standing armies. Disciplined and drilled, clad in armour and helmets of leather, and equipped with swords and halberds, the new model armies were more than a match for the chariot-chasing levies even before the introduction of forged iron and the deadly crossbow.

These important innovations seem to have originated early in the fourth century BC and in the south, where Wu was famed for its blades and where Chu graves have yielded some of the earliest examples of the metal triggers used for firing crossbows. Never far behind any technological innovation, scholarly treatises provide evidence of warfare being elevated into an art. A shi called Sun Bin, also from the south, is credited with the first text in which the crossbow is described as ‘the decisive element in combat’.29 Sun Bin also mentions cavalry, a novelty in that the art of fighting from horseback was as yet little understood. A famous discussion on the merits of trousers over skirts that took place in the state of Zhao in 307 BC seems to mark the adoption of the nomadic practice of sitting astride horses rather than being drawn along behind them in chariots. But cavalry were used largely for reconnaisance and their numbers were small. Mozi, that stickler for non-aggression, manages under the rubric of self-defence to reveal the development of a much more sophisticated level of siege warfare, including the use of wheeled ladders for wall-scaling and smoke-bellows to counter tunnellers. Cities had long been fortified, but it was in the ‘Warring States’ period that chains of garrisoned forts linked by ‘long walls’ first receive mention. Partly to define territory, partly to defend it, ‘long walls’, bits of which would later be incorporated into Qin’s supposed ‘Great Wall’, were perhaps the most obvious manifestation of state formation.

Universal conscription naturally meant that armies were much bigger. At the great battle of Chengpu in 632 BC each side had supposedly mobilised up to 20,000 men. By the beginning of the ‘Warring States’ period, armies are thought to have numbered around 100,000, and by the third century BC several hundred thousand. Battle-deaths running to 240,000 are mentioned but are presumed to be exaggerations. The slaughter was nevertheless on an unprecedented scale; the battles sometimes lasted for weeks, and prisoners-of-war could expect no mercy; their numbers, like their heads, were simply added to the body-count.