Полная версия

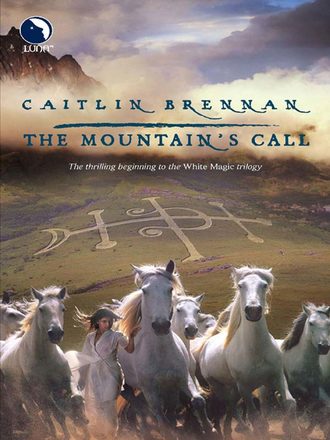

The Mountain's Call

The others were slower to choose. Embry hesitated between a pretty sorrel and a plainer but steadier-looking bay. He chose the bay, with a glance at Paulus that told Valeria he had seen the point of the test.

Valeria made herself stop watching the others and make a decision for herself. Iliya had taken the ugliest of the horses, a hammerheaded brown mare whose eye was large and kind. She was well built except for the head, with a deep girth and sturdy legs. Valeria might have taken her if Iliya had not got there first.

The rest of the horses varied in size and looks, but for the most part they were alike in quality. As she debated the merits of one and then another, she could not help noticing that Batu stood apart from the others with a look almost of terror on his face.

She slipped from the line and went to stand beside him. “You haven’t seen much of horses, have you?” she asked.

He shook his head. “The Call when it came was a terrible shock. I should never have listened to it, but it gave me no choice. Do you think, if I leave now, it will let me go?”

“Don’t leave,” she said. “It wanted you. It must have felt you were right for it, even if horses are strange to you. Is there any one here that makes you feel righter than the others?”

He started to shake his head again, but then he stood still. His eyes narrowed. “That one,” he said, pointing with his chin at a stocky dun. “That feels…” His eyes widened. “She says—she says come here, don’t be a fool, don’t I know enough to listen when someone is talking to me?”

Valeria laughed. “Then you had better go, hadn’t you?”

He hesitated. “But I still don’t know—”

“She’ll tell you,” Valeria said.

The mare shook her head and stamped. Her impatience was obvious. Batu let go of his uncertainty just long enough to obey her.

The mare would look after him. Valeria turned back to her own testing. She was the last to choose. The others were already busy with brushes and curries and hoof picks.

She would do well to take her own advice. One horse on the end, another mare, looked as if she had been waiting patiently for the silly child to notice her. She was a bay with a star, stocky and cobby. If she had been grey, Valeria would have taken her for one of the white gods.

We are not all greys. The voice was as clear as if it had spoken aloud. There was a depth to it, a resonance, that shivered in Valeria’s bones.

Horses never stooped to words if they could avoid it. The fact that the mare had done so was significant. Valeria bowed to her in apology and deep respect. She could feel Petra’s approval on her back like a ray of sun. This was his mother, and she had chosen to be included with the common horses. It was unheard of for the Ladies to do such a thing, but they did as it best pleased them.

The mares had distinct preferences in grooming and deportment. Valeria knew better than to argue with them. When the mare’s coat was gleaming and her mane and tail were brushed to silk, the groom who had held her brought a saddle and a bridle. She was even more particular about those.

If this had not been a test and therefore deadly serious, Valeria would have been enjoying herself. She even had time while grooming and saddling to watch the drama at the other end of the line, where Paulus was discovering that he really, truly was not an imperial duke here.

He had stood for some time, holding the golden horse’s lead, until he realized that none of the grooms would respond to his glances, his lifts of the chin, or even his snaps of the fingers. The one assigned to his horse had brought a grooming box and left it. Eventually it dawned on him that he was expected to groom his horse himself.

He drew himself up in high dudgeon. Before the words could burst out of him, he caught Kerrec’s pale cold eye. Something there punctured his bladder to wonderful effect.

Valeria was dangerously close to approving of Kerrec just then. Paulus struggled almost as badly as Batu, but he struggled in silence. Batu, she noticed, was listening to his mare, and while he was awkward and often fumbled, he did not do badly at all. Paulus paid no attention to his horse’s commentary, such as it was. The horse truly was not very bright.

At last they were all done. The horses were groomed and saddled, with the would-be riders waiting beside them. Kerrec walked down the line, pausing to tighten a girth here and tuck in a strap there. When he came to Paulus, he arched a brow at the groom. The man came in visible relief and, deftly and with dispatch, untacked and then retacked the horse.

Paulus’ face went red and then white. When the groom handed the reins back to him with the bridle now properly adjusted and the saddle placed where it belonged, he held them in fingers that shook with spasms of pure rage.

Batu did not have to suffer a similar ignominy. Apart from a slight adjustment of the girth, Kerrec found nothing to question. The dun mare flicked a noncommittal ear. She was a good teacher and she knew it.

Valeria was the last to be inspected. She held her breath. Her stomach was tight.

Kerrec slid his finger under the girth and along the panel of the saddle. He tugged lightly at the crupper, which won him a warning slide of the ear from the mare. When he reached for the bridle, she showed him a judicious gleam of teeth.

He bowed to her and stepped back. Valeria found that gratifying, though it would have been more so if he had shown any sign of temper.

He seemed already to have forgotten her. “Now of course we will ride,” he said. “One by one and on my order, you will do exactly as I say. Is that understood?”

Several had been ready to leap into the saddle and gallop off. They subsided somewhat sheepishly.

“Valens,” said Kerrec. “Mount and stand.”

Valeria started. She had been expecting to be called last as before. Naturally he had seen how she relaxed for what she expected to be a long wait, and had done what any self-respecting drill sergeant would do.

She scrambled herself together. He was tapping his foot, marking the moments of the delay. Even so, she took another half-dozen foot-taps to take a deep breath, center herself, and get in position to mount properly. The bay mare stood immobile except for the flick of an ear at some sound too faint for Valeria to hear.

Valeria mounted with as little fuss as possible, settled herself in the saddle, and waited. As usual Kerrec gave no sign of what he was thinking. “Walk,” he said.

The test was simple to the level of insult. Walk, trot and canter around the grassy square in both directions. Turn and halt, proceed, turn and halt again. Dismount, stand, bow to the First Rider. Return to the line and watch each of the others undergo the same stupefyingly simple test.

Iliya, who was third to ride, was already bored with watching Valeria and Marcus. When he was asked to canter on, he accelerated to a gallop and then, just as his horse would have crashed into the wall, sat her down hard, pivoted her around the corner, and sent her off again in a sedate canter. His grin was wide and full of delighted mischief.

“Halt,” said Kerrec. He did not raise his voice, but the small hairs rose on Valeria’s neck.

The hammerheaded mare stopped as if she had struck the wall after all. Iliya nearly catapulted over her head.

“Dismount,” said that cool, dispassionate voice. Iliya slid down with none of his usual grace. His knees nearly buckled. He caught at the saddle to steady himself.

“Return to your place,” Kerrec said.

Iliya’s face had gone green. He slunk back to his place in the line.

After that no one tried to brighten up the drab test with a display of horsemanship. Even Paulus followed instructions to the letter.

He was the last. When he had gone back to his place, Kerrec sent them to the stables to unsaddle, stall, and feed their horses. They were all on their guard now, knowing that every move was watched. It made them clumsy, which made them stumble. To add to the confusion, the horses responded to the riders’ tension with tension of their own.

Marcus tripped over a handcart full of hay that Cullen had left in the stable aisle, and fell sprawling. Cullen burst out laughing. Marcus went for his throat.

Cullen reeled backwards. His hands flailed.

Almost too late, Valeria recognized the gesture. She flung herself flat.

Embry was not so fortunate. He had paused in forking hay into his horse’s stall to watch the fight. The bolt of mage-fire caught him in the chest.

Valeria tried from the floor to turn it aside. So did Iliya from the stall across from Embry. They were both too slow.

Embry burned from the inside out. He was dead before his charred corpse struck the floor.

Marcus rolled away from Cullen. Cullen stood up slowly. His face, which had seemed so open and friendly, was stark white. The freckles stood out in it like flecks of ash.

“Someone fetch the First Rider,” Paulus said. His voice was shaking. “Quickly!”

Valeria was ready to go, though she did not know if her legs would hold her up. The backlash of the mage-killing had left her with a blinding headache. When she tried to get up, she promptly doubled over in a fit of the dry heaves.

Someone held her up. She knew it was Batu, although she was too blind and sick to see him.

Kerrec’s voice was like a cool cloth on her forehead. That was strange, because his words were peremptory. “All of you. Out.”

Batu heaved her over his shoulder and carried her out. She lacked the energy to fight. By the time she came into the open air, she could see again, although the edges of things had an odd, blurred luminescence.

Batu set her down on the grass of the court. Dacius was doing the same for a thoroughly wilted Iliya. Paulus stood somewhat apart from them, as if they carried a contagion.

It was a long while before Kerrec came out of the stable. Two burly grooms followed. One led Cullen, the other Marcus. Their hands were bound, and there were horses’ halters around their necks.

Dacius’ breath hissed. Iliya and Batu did not know what the collars meant. Paulus obviously did. So did Valeria.

She watched with the same sick fascination as when Kerrec executed justice on the man who tried to rape her. Just as she had then, she was powerless to move or say a word.

Master Nikos rode into the court through one of the side gates. A pair of riders followed him. Their stallions were snow-white with age and heavy with muscle. They walked like wrestlers into a ring, light and poised but massively powerful.

The Master halted. The riders flanked him.

There was no trial. There were no defenses spoken. Only the Master spoke, and his speech was brief.

“Discipline,” he said, “is the first and foremost and only rule of our order. It must be so. There can be no other way.”

He raised his hand. The grooms led the two captives to the center of the court and unbound their hands.

They did not move. Valeria saw that they could not. The binding on them was stronger than any rope or chain. It was magic, so powerful it made her head hum.

The riders rode from behind the Master. As they moved off to the right and the left, the stallions began a slow and cadenced dance with their backs to the condemned. The steps of it drew power from the earth. It came slow at first, in a trickle, but gradually it grew stronger.

The two on foot, the one who had killed and the one whose loss of discipline had caused the other to kill, began to sway. Their faces were blank, but their eyes would haunt Valeria until she died.

The end was blindingly swift and blessedly merciful. The stallions left the ground in a surge of breathless power. For an instant they hovered at head-height. Then, swift as striking snakes, their hind legs lashed out.

Both skulls burst in a spray of blood. Not a drop of it touched those shining white hides. The stallions came lightly to earth again, dancing in place. The bodies fell twitching, but the souls were gone.

The stallions slowed to a halt and wheeled on their haunches to face the stunned and speechless survivors.

“Remember,” said Master Nikos.

Chapter Eight

“And they said this test wasn’t deadly.” Iliya had stopped trying to vomit up his stomach, since there was nothing in it to begin with.

They had been sent back to the stable to finish what they had begun. Embry’s body was gone. The only sign of it was a faint scorched mark on the stone paving of the aisle. The horses were still somewhat skittish, all but the bay Lady who had selected Valeria for the testing. It was done, her manner said. There was no undoing it. Hay was here, and grain would come if the human would stop retching and fetch it.

Her hardheaded common sense steadied Valeria. The testing would not end because two fools and an innocent had died.

“This is war,” Batu said. “That was justice of the battlefield.”

“It was barbaric,” Dacius said. He had been even quieter than usual since Embry died, but something in him seemed to have let go. He flung down the cleaning rag with his saddle half-done. “This is supposed to be the School of Peace. What do they do in the School of War? Kill a recruit every morning and drink his blood for breakfast?”

“Take dancing lessons,” Iliya said, hanging upside down from the opening to the hayloft. “Learn to play the flute.” He dropped, somersaulting, to land somewhat shakily on his feet. “Don’t you see? It’s all turned around. War is peace. Peace is war. And if you let go and kill something—” He made a noise stomach-wrenchingly like the sound of a hoof shattering bone. “Off with your head!”

“How can you laugh?” Dacius demanded. “Did the mage-bolt addle your brain?”

“That depends on whether I have a brain to addle.” Iliya snatched the broom out of Batu’s hands and began to sweep the aisle. He swept the scorched spot over and over and—

Batu caught the broom handle above and below his hands, stilling it. Iliya looked up into the broad dark face. “We’re all going to fail,” he said.

“We are not.” The words had burst out of Valeria. As soon as they were spoken, she wished they had not been. Everyone was staring at her.

She gritted her teeth and went on. “Do you know what I think? I think we’re the strongest. The best mages, or we could be the best.”

“How do you calculate that?” Paulus asked in his mincing courtier’s accent.

“Cullen had no self-control,” she answered, “but he was strong enough to kill. Marcus was trying to strangle him with more than hands. Embry thought he could stop a mage-bolt.”

“It’s far more likely we’re the idiots’ division,” Paulus said with a twist of the lip. “Three of us died for nothing before the first day was half over. Does any of you begin to guess how much more difficult the rest of the testing will be? We couldn’t even keep the eight together for a day.”

His logic was all too convincing, but Valeria could not make herself believe it. “The strongest can be the weakest. It’s a paradox of magic.”

“I know that,” he said. “Which school of mages were you Called from? Beastmasters?”

“Apprentice mages can be Called?” That she had not known. “Were you—”

“I was to go to the Augurs’ College,” Paulus said as if she should be awed. “So were you a Beastmaster?”

“No,” she said.

“Ah,” he said. He shrugged, almost a shudder. “It doesn’t matter, does it? We’ll all leave as Cullen did—in a sack.”

She had been thinking of him as older than the others. He carried himself as if he were a man fully grown, afflicted with the company of children. She realized now that he was terribly scared, and that he was no older than she.

It did not make her like him any better. It did soften her tone slightly as she said, “Stop that. If this magic is discipline, then part of discipline is teaching ourselves to carry on past fear.”

“I’m not afraid!”

“Don’t lie to yourself,” Dacius said. “We’re all afraid. We thought we’d learn to ride horses, work a few magics and after a little while we’d be in the Court of the Dance, weaving the threads of time. It wasn’t going to be terribly hard. The worst pain we’d suffer would be bruises to our backsides when we fell off a horse.”

“That’s absurd,” Paulus snapped. “I never thought it would be easy. You commoners, you hear the pretty stories and think it’s as simple as a song. It’s the greatest power there is.”

“I heard,” said Batu, “that no one who wants it can have it. Wanting taints it. Power corrupts.”

“You have to want the magic,” Valeria said, “and the horses. That’s a fire in the belly. A rider can’t rule, that’s the law. He serves and protects. He’s no one’s master.”

“You recite your lessons well,” Paulus said. “The truth is what you saw out there. It’s death to lose control. That’s what it comes to. Discipline or death.”

“Then we had better be disciplined,” said Valeria.

Dinner was as much water as any of them could drink. It was pure and cold, like melted snow.

“Water of the fountain,” Paulus said as he tasted it. For the first time he sounded capable of something other than scorn.

Valeria could taste the heart of the Mountain in that water, fire under ice. It satisfied her hunger so well that she did not even think of food.

Sleep struck her abruptly as she got up from the table. She staggered up the short flight of stairs and into the sleeping room. She was just awake enough to kick off her boots before she fell into bed.

The dream was waiting for her. It was full of white horses as always, but for the first time since the Call came, there were riders on their backs.

She recognized the place from a hundred stories. It was a high-ceilinged hall somewhat larger than the open court in which Marcus and Cullen had died. Tall windows let in white light. At the end, framed by a vaulted arch, the Mountain gleamed through the tallest and widest window that Valeria had ever imagined, with glass so pure that not a bubble marred its surface.

The floor of the hall was raked white sand. Pillars of marble and gold rimmed it, holding up a succession of galleries. Three rose on either side. In the lowest gallery opposite the Mountain, in a box by themselves, three Augurs stood in their white robes and conical caps. A secretary sat just behind them with tablets and stylus.

Under the Mountain was a single gallery. Draperies hung from it, crimson and gold. In the back of it was the banner of imperial Aurelia, golden sun and silver moon interlaced under a crown of stars, gleaming against a crimson field. On either side of it hung two others. One was luminous blue, with a silver stallion dancing against the unmistakable conical shape of the Mountain. The other was the golden sunburst on crimson of the imperial house.

This was the Hall of the Dance, where the white gods danced the patterns of fate and time. In her dream they were entering as they had come to the place of the testing, eight of them in a double line, walking in that slow and elevated cadence which was distinct to their kind.

She recognized the riders’ faces. Master Nikos led one line, First Rider Kerrec the other. Rider Andres rode behind the Master. She would learn the others’ names as the testing went on. They would be her partners and companions when—if—she passed the testing.

Someone was sitting in the royal box under the gleam of the Mountain. She expected to see the emperor as he was depicted on his coins, a stern hawk-faced man with a close-clipped beard. Instead it was a young woman with a face as cleanly carved as an image in ivory. She was dressed very plainly in a rider’s coat and breeches, and her hair was in a single plait behind her. The elaborate golden throne on which she sat seemed gaudy and common against that unflawed simplicity.

Only after Valeria had examined her thoroughly did she find the emperor. He stood behind the throne with his hand on the young woman’s shoulder, dressed in rider’s clothes as well. He was younger than Valeria had imagined, and less stern. His hair was still black, although his beard was iron-grey. His eyes were warm, smiling into hers. Magic sang in him like the notes of a harp.

He reminded Valeria of Kerrec. It was certainly not his warmth or the smile in his eyes—grey eyes, not as pale as Kerrec’s, but still unusual in this dark-eyed country. Take off the beard and the smile and thirty years, and there was the First Rider to the life.

Could it be…

The emperor had one living son, and he was half-barbarian, which Kerrec certainly was not. Another, legitimate son, the heir, had died years ago, leaving his sister to take his place. Kerrec must be related in some convoluted degree, like every noble and half the commoners in Aurelia.

In the shadows behind the emperor, a man was standing. Valeria could not quite make out his face. He was taller and wider in the shoulders than the emperor, but somehow he seemed stunted. Something was wrong with him, something that crept out toward the emperor and surrounded him with a flicker of darkness and a flash of sudden scarlet.

In the hall below them, the riders began the Dance. She could almost understand the patterns. They were following the skeins of destiny, tracing them in the raked earth of the floor. The air hummed subtly, and the light began to bend. Time was shifting, flowing. The stallions swam through it like fish through water. The riders both guided and were guided by them. The magic ruled them even as they ruled it.

With no sense of transition, she had become part of the Dance. The stallion she had dreamed before, the young one with the faint dappling, carried her through the movements.

She simply sat on his back. When the time came, she would guide him, but in this dream he was her teacher. There was a deep rightness in it. This, she was made for.

When the bell rang before dawn, she was awake and refreshed. The others woke groaning or cursing and dragged themselves out. There was no breakfast, not even water, but Valeria did not miss it. The water of the fountain was still in her. Batu, she noticed, seemed at ease. The others were pale and hollow-eyed.

They had their orders from the night before. There were horses to feed, stalls to clean. When they were done, they had to find their way to a certain room within the school. It was middling large and middling high, and filled with desks and benches. Each desk held a stack of wax tablets and a cup of sharpened styli.

The rest of the eights were there already. None of them had lost a single member, let alone three. They drew away from the latecomers, whispering among themselves.

Valeria exchanged glances with the others. She lifted her chin. So did Paulus. The other three followed their lead. They marched boldly down to the front of the room and took the seats that had been left for them there, separated somewhat from the rest.

Valeria ran a finger over the tablet in front of her. It was a smooth slab of wood coated with wax, blank and ready to be written on.

She had not expected to find herself in a schoolroom, even though this place was called a school. All the schooling, she had thought, would be in the stable and on the riding field. It was odd to think of book-learning here.

She looked up from the tablet to find Kerrec at the lectern. He had come in so quietly that she had not even heard him. Neither had any of the others, she noticed. The buzz of conversation was rising to a roar.

He cleared his throat. The silence was instant and complete. “Today we test knowledge,” he said. “If any of you is unable to read or write, go now with Rider Andres. You will be tested elsewhere.”

“And failed?” asked Paulus.

There were a few gasps at his daring. Kerrec answered as coolly as ever. “No one fails for simple lack of skill.”

“Then what do we fail for?”

“Lack of understanding,” said Kerrec. He looked away from Paulus, dismissing him.

One by one, a dozen of the Called rose, clattering among the benches, and made their way toward Rider Andres. Batu was not one of them, which surprised Valeria somewhat. Iliya was. He glanced back before he passed through the door. He was openly scared, but he grinned through it and saluted them.