Полная версия

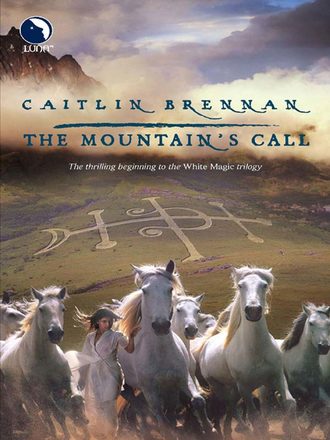

The Mountain's Call

Before the storm came, she had met few people on the road. Most of those were farmers going to market. She had seen an imperial courier once, galloping flat out on his spotted horse.

A troop of legionaries tramped past not long after she left the barn. She resisted the urge to hide from them. She was not a fugitive. She was Called. Her horse, bridleless and saddleless and obeying her without question, would tell anyone that. So would the road she was on, which led north to the Mountain and the white gods.

In the stories she had heard, the Called could ask for food and lodging at the imperial way stations. The day after the last of her provisions ran out, she tested it. It was that or resort to stealing.

The man in charge of the station had the same toughened-leather look as her father, and the same accent, too. Wherever a legionary came from, after twenty years in the emperor’s service he came out talking that way, usually with a voice gone raw from bellowing orders in all weathers above all manner of uproar.

He did not ask her who she was or what she was doing. As she had hoped, it was obvious. He gave her a seat at the table in the mess hall and a bed in the barracks, and showed her where she could stable the horse. When the horse was bedded down with a manger full of good hay and a pan of barley, she went to claim her own dinner.

There were only a handful of other people in the station tonight. They were all imperial couriers either resting between runs or waiting for the relay to reach them. Most of them, like the stationmaster, asked no questions. One or two watched her without being blatant about it. They all seemed to know each other. She was the only stranger.

She finished her dinner as quickly as she could, trying not to choke. She barely tasted the stew and bread and beer. She escaped before anyone could strike up a conversation.

She left before the sun came up. The cook was just taking the first loaves out of the oven when she came down from the room. He gave her a loaf so hot and fresh she could barely hold it, with a wedge of cheese thrust into a slit in the crust. The cheese had melted into the bread. She ate it in a state of bliss, and belched her appreciation.

“Gods give you good luck,” the cook said, “and a safe journey. May the testing favor you.”

She hoped she did not look too startled. “Thank—thank you,” she said.

The cook smiled and touched her forehead. “For luck,” he said. “Never had anyone Called from your village before, did you?”

She shook her head. “I’ve heard all the stories. But—”

“You give luck,” the cook said, “and take it, too. Stop at the stations. Don’t try to go it on your own. Most people respect the Call, but a few might try to steal the luck.”

“How do they—”

The cook slashed his hand across his throat. “It’s in the blood, they say. I don’t believe it—I think it’s in the soul, and killing you unmakes it. Those on the Mountain, they know for sure, but they’re not telling the likes of us.”

“I don’t know anything about it,” Valeria said.

“You’ll learn,” said the cook. “Best be on your way now. It’s a long way to the Mountain, and time’s not standing still.”

“How long—”

“Three days for a courier,” the cook said. “Ten, maybe, at ordinary pace, and allowing for weather and delays. Ask at the stations if there’s a caravan heading the way you need to go. That’s safest. You might even meet others of the Called.”

A shiver ran down her spine. In her dreams she had always been alone. She had not thought about what the Call would mean. She went to a place where everyone had the same kind of magic as she did. She would not be alone any longer.

If and when they found out she was not a boy—

She would deal with that when it happened. For now she had to go to the Mountain. That was all she could think about, and all she needed to think about.

When she fetched the horse from the stable, having discovered that she could commandeer a saddle and bridle for him, she was struck with a sudden attack of cowardice. She turned him southward, back the way she had come.

The Call snapped like a noose around her neck. She almost lost her breakfast. She turned northward and saved it, but the message was clear. She was bound to this road. She had to ride it to the end.

The hunt passed her not long after the sun came up. The hounds came first, then the huntsmen. The hunt itself was a little distance behind. She had seen few nobles in her life, but these were obviously wellborn. Their horses’ caparisons were elaborate, with ornately tooled saddles and chased silver bits and stirrups. The long manes were braided with ribbons in colors that matched the riders’ coats. The riders wore enough gold to dazzle her.

They looked down their noses at the lone traveler on the side of the road. She felt grubby and common in her patched coat. Her boots were walking boots—one of the lordlings remarked on them as he rode elegantly by. The horse was still in winter coat. Even a good grooming could not make him look less shaggy.

Valeria lifted her chin and looked the riders in the eye. She was Called. And what were they?

As soon as she did it, she knew she had made a mistake. One of them, big and uncommonly fair-haired for this part of the world, raked her with a glance that sharpened suddenly. She had seen that look in the leader of a dog pack that had been going casually about its business until it caught wind of a newborn lamb. This was the same sudden gleam in the eye, the same flash of fang.

He was not hunting to eat. He was hunting for pleasure. It mattered little to him whether his prey was animal or human.

Valeria kept the horse, and herself, perfectly still. It might be too little too late, but she called up what magic she could in her rattled state, and did her best to seem as dull and unworthy as possible. Above all, she took care not to give him any further indication that she was one of the Called. If anyone would kill her for luck, this man would.

It seemed to work. The nobleman let his eyes slide away from her. The rest of them rode past without stopping or pausing, with only brief glances if they troubled with her at all.

Valeria nearly collapsed in relief. She was safe, she thought. Even so, she stayed where she was for long enough to see how, just before the road bent around a hill, they turned off into the trees. Then she waited a while longer, until she was sure she no longer heard them.

When she rode on, she stayed well away from the path through the trees, keeping to the open road. It curved again, then again, weaving through a range of wooded hills.

Gradually the hills closed in. The trees were taller, their branches laced overhead. The bright sunlight dimmed, filtering through needles of spruce and pine. There was still snow here. It had a deep cold smell under the sharp sweetness of evergreen.

The horse arched his neck and tensed his back. When a bird started out of cover, he almost went skyward with it.

Valeria soothed him with a purring trill, stroking his neck over and over. It softened a little. He went forward on tiptoe. Every now and then he expressed himself with an explosive snort.

The hunt found Valeria just where the road opened again and started to descend into a deep river valley. In the distance she saw the roofs of a town. It was a substantial place, with a wall around it and the tower of a temple rising out of it.

She heard the hounds singing. Whatever they were chasing, it was coming this way.

Best be out of its way when the hunt came through, she thought. She was not afraid—yet. She let the horse pick up a trot and then a canter, aiming toward the town.

By the time she came out on the level, the hounds were in full cry behind her. The horse had forsaken any pretense of civilization. He felt himself a hunted thing. He knew nothing but speed.

His panic was sucking her down. She fought it. The hounds were closing in. She could not see or hear the huntsmen, or the nobles on their pretty horses. They must be far behind. Or—

Just as she turned from looking back at the hounds, their masters rode out of the trees ahead. They were laughing. Their leader laughed loudest of all, mocking her stupidity. This was an ambush, and she had ridden blindly into it.

The horse had the bit in his teeth. She let the reins fall on his neck as he veered wildly away from the onrushing horsemen, and sang to the hounds.

They had the taste of blood from a doe that they had caught and torn apart under the trees. The horse was larger and sweeter. She sang away the sweetness and the temptation. She sang them to sleep.

They dropped where they ran, tumbling over one another. It happened none too soon. The horse was flagging. He was a sturdy beast, but he was not built to race.

The hunters on their slender-legged beauties were gaining fast. Her horse’s twists and evasions barely gave them pause. They ran right over the hounds.

There were too many horses to master all at once, and Valeria was tired. Her own horse stumbled just as she scraped together the strength to try another working. His legs tangled, and he somersaulted. They parted in midair.

She lay winded, wheezing for breath. Her head was spinning. Huge shapes swirled around her. Gold flashed in her eyes. Hands wrenched at her, tearing at her clothes.

She fought blindly, still struggling to breathe. The magic was beaten out of her. She kicked and clawed. Her coat was gone. Her shirt shredded in their hands.

Her breasts gave them pause, but that was all too brief. They yowled with glee. It would not have mattered if she had been a boy. A girl was much, much better.

Two of them pinned her arms. Two more pried her legs apart. The fifth, whose face she already knew too well, stood above her, tugging at his belt.

She arched and twisted. She was completely empty of rational thought. Magic—she had magic somewhere. If she could only—

The earth shrugged. The hot, hard thing that had been thrusting at her dropped away. Her wrists and ankles throbbed so badly that for a long while she was not even sure that they were free.

Someone bent over her. She surged up in pure, blind rage.

He rocked back a step, but then he braced against her. He caught her hands and held her at arm’s length.

All too slowly she understood that he was not one of the hunters. He wore no gold. His coat was plain leather. The hunters had been big men, brown-haired, with broad red faces. She would never forget any of those faces. This one was slim and dark and not much taller than she. His eyes were an odd pale color, almost silver. With his thin arched nose and long mouth, they made him look stern and cold.

She looked around dazedly. Her attackers lay like the wreck of a storm, heaped one on top of the other. Their horses stood beyond them in a neat line.

A small wind began to blow, stinging her many scratches. She turned her wrists in her rescuer’s grip. He let her go. She started to cover herself, but it was a little too late for that.

Mutely he took off his coat and held it out. She took it just as wordlessly. As plain as it was, it was beautifully made, of leather as soft as butter. The shirt he wore under it was fine linen, and clean. She caught herself admiring the width of his shoulders.

Her stomach turned over. She barely had time to toss the coat out of the way before she doubled up, retching into the grass.

She was beyond empty when she could finally stand straight again. Her head felt light, dizzy. She started to reach for the coat and staggered.

The dark man caught her before she fell. Her skin flinched at his touch, but she made it stop. His lips tightened. “Sit here,” he said, pointing to his coat where it lay on the ground.

He had a deeper voice than she had expected, speaking imperial Aurelian with an accent so pure it sounded stilted. He must be from the heart of the empire, from Aurelia itself.

She did not consciously decide to do as he told her. He let go of her, and her knees would not hold her up. She crumpled in a heap.

He turned his back on her and walked away. She stared after him in disbelief. Anger drove out a storm of tears. How could he—what did he think—

She was shaking uncontrollably. Her stomach had nothing more to cast up. If she could find the horse, she would get to him and mount somehow and escape before her rescuer came back.

The horse was dead. Maybe she had felt him die. She did not remember. He lay not far from her with his neck at an unnatural angle. Flies were already buzzing around him.

The other horses were still in their line as if tied. She supposed she should wonder at that, just as she should grieve for the horse who had served her so well. She would, later. She was in shock. She knew that dispassionately, from the training her mother had bullied into her. She needed warmth, quiet and a dose of tonic.

The sun was not too cold. It was quiet where she lay. None of her attackers had moved, but they were breathing. She could hear them. They must be asleep or unconscious.

The dark man swam into view above her as he had before. This time she simply stared at him. He carried a bundle that unfolded into a shirt as fine as his own, a pair of soft trousers, and a pair of boots. The boots were for riding.

He dressed her as if she was a child. These clothes were better than the best she had had at home. They fit much better than her brothers’ hand-me-downs.

When she was dressed, with his coat over the shirt, he filled a wooden cup from a wineskin and made her drink. She swallowed in spite of herself, and choked. The wine was so strong it made her dizzy. There was something in it. Valerian—hellebore—

She pushed the cup away. “Are you trying to poison me?”

“So,” he said. “You can talk. No, it’s not poison. It’s something to calm you.”

“Not for shock,” she said. “That makes it worse. Plain water is better. And rest. If there’s an herbalist in the town—”

“I’m sure there is,” he said. “Can you ride?”

“I can ride anything.”

That was the wine making her giddy. He arched a brow but refrained from comment. “I meant, can you ride now?”

“Anything,” she said. “Any time.”

“If you say so,” he said. He turned toward the line of horses. One of them shook its head as if he had freed it from a spell, and walked docilely toward him. It was a handsome thing as they all were, coal-black with a star. Its trappings were crimson and green.

He smoothed the mane on its neck, grimacing at the ribbons, and said to Valeria, “We’ll get you something less gaudy in Mallia.”

“You’ve been very kind,” she said. “You saved my life and more, and I’m very grateful. But now I think—”

“Don’t worry,” he said. “You won’t be charged with stealing the horse. It’s due you as compensation—and not only for rape. This is one pack of hellions that won’t be terrorizing these parts again.”

She stared at him. “Again? This isn’t the first—”

“They’re notorious,” the dark man said. “And, unfortunately, too well born to be brought to account. The emperor’s justice is not as well administered here as one might hope.”

“But that means—you—I—”

“Their hunting days are over,” the dark man said. His voice was as soft as ever, but something in it made her shiver.

Valeria’s sight was blurring again. She had meant to say something more, but what it was, she could not remember.

While she groped for words, he lifted her and deposited her lightly in the saddle. He was a great deal stronger than he looked. She was almost as big as he was, and he had not shown any sign of strain.

She clung to the high ornate saddle and tried to stop her head from whirling. The horse was quiet under her. It found her weight negligible after the well-fed lordling it had been carrying, and her balance even in this state was better than his.

Her rescuer made no move to claim any of the horses for himself. He walked through the field of the fallen. Most he left where they lay, but he paused beside one. When he turned the man onto his back, Valeria recognized the face. It had hung above her just before the earth shook and flung them all down.

The man’s breeches were tangled around his ankles. His thick red organ flapped limply. Her rescuer bent over him. There was a knife in his hand.

Valeria’s throat closed. She knew the penalty for rape. Except that this man had not quite—

She meant to say so. The words would not come. She watched without a sound as the dark man made two quick, merciless cuts. It was just like gelding a colt. He flung the offal with a gesture of such perfectly controlled fury that her jaw dropped. Before the bloody bundle could strike the ground, a crow appeared out of nowhere and caught it and carried it away.

When the man turned back toward her, his eyes were so pale they seemed to have no color at all. He lifted a shoulder just visibly.

The horse on the end of the line left the others and trotted toward him. Now that she saw it apart from the rest, she realized that it was different. Its saddle and bridle were as plain but as excellently made as the rider’s clothes. The horse was very like them in quality, a sturdy grey cob with an arched nose and an intelligent eye. It was neither as tall nor by any means as elegant as the others, but Valeria would have laid wagers that it would still be going when they had dropped with exhaustion.

The dark man mounted without touching the stirrup. With no perceptible instruction, the grey horse turned toward the town. The black followed of its own accord.

The movement of a horse under her did as much to bring Valeria back to herself as anything she could have done. Her stomach was a tight and painful knot, but she had mastered it.

She would have to decide how she felt about the dark man’s rough justice. The civilized part of her deplored it. The sane part was wondering what price he would pay for it, if the lordling’s family really was as powerful as he had said. The rest of her was dancing with bloodthirsty glee.

She fixed her eyes on him to steady herself. He had a beautiful seat on his blocky little horse. He sat upright but not at all stiff, with a deep, soft leg and a supple hip. He moved as the horse moved, as if he were a part of it.

She had never seen anyone ride like that, except in dreams. If the riders on the Mountain could teach her to ride even a fraction as well, she would call herself happy.

She tried to imitate him, a little. The effort reminded her forcefully that she had been tumbling on rocky ground and fighting off rape not long before. She persisted until the memory faded. Then there was only the horse under her and the rider in front of her and the town of Mallia drawing steadily closer.

Chapter Three

The hostages joined the caravan in Mallia. They had been riding at a punishing pace, thanks to their escort. The emperor’s guard had no love to spare for the sons of barbarian chieftains who had made war against the empire. Even if the emperor had seen fit to take them as hostages for their fathers’ good behavior, the emperor’s soldiers saw no reason to treat them as anything but enemies.

Euan Rohe had a tougher rump than most. But after far too many days on imperial remounts, with a change at every station and a bare pause to eat or piss, he was hobbling as badly as the others. He groaned in relief when he heard that they were to stop for a whole night in this little pimple of a town.

For a town this small and this close to the heart of the empire, it had a sizable garrison. There was a legion quartered here under an elderly but able commander. He inspected his temporary charges with a singular lack of expression and said to his orderly, “Clear out the west barracks. Tell the veterans to keep their opinions to themselves, or they’ll be answering to me.”

Euan felt his brows go up. There had been no need for the man to say that in the hostages’ hearing. It was a challenge of sorts, and a warning.

They had had a good number of those as they rode from the frontier. He knew better than to take them for granted. A hostage survived by staying on guard.

The west barracks made a decent prison. Its windows were high and barred, and the guards took station near the doors. It seemed excessive for half a dozen hostages, but that was the empire of Aurelia. It did everything to excess.

The hostages were determined not to cause trouble. There would be enough of that later, the One God willing. They ate what they were fed and went directly to sleep.

It was still dark when they were rousted out. The caravan was just starting to assemble. It was a merchant caravan for the most part, but some of it was even more heavily guarded than the hostages. That was the treasure transport, carrying coin and tribute to the school on the Mountain.

Euan was in no way eager to climb into the saddle. He delayed as long as he could, which was a fair while with a caravan of this size.

As he busied himself with the sixth or seventh readjustment of a bridle strap, the commander came out of the legionaries’ barracks with a pair of his countrymen. They were both much younger than he. One was a hawk-faced man who walked like a warrior, light and dangerous. The other was a boy. Or…

Euan peered. Boys could be beautiful in Aurelia, with their smooth olive skin and black curly hair. He had mistaken a few for girls in his time, and been royally embarrassed by it, too. This must be a boy. Girls in this country wore skirts and did not cut their hair. And yet…

This was interesting. He busied himself with his horse’s girth and watched under his brows. The commander and the hawk-faced man took the boy, if boy it was, to the caravan master. Euan could not hear every word they said, but it was clear the young person was being entrusted to the caravan for transport north.

The boy did not say anything while they made arrangements for him. His eyes were wide, taking in the caravan. They widened even further as he caught sight of the hostages in their ring of guards. From the look of him, he had never seen princes of the Caletanni before.

Euan rather thought the boy liked what he saw. He would probably die before he admitted it. Gavin favored him with a broad and mocking grin. The boy looked away hastily.

The negotiations were short and amicable. Whoever the hawk-faced man was, he won a degree of respect from the caravan master that even the legionary commander could not match. The boy must be a relative, from the way the caravan master treated him.

The boy broke his silence when the horses were brought out. His horse was a pretty black of a much lighter and more elegant breed than Euan’s big dray horse. He seemed to be looking for another, and not seeing it. “Aren’t you coming?” he asked the hawk-faced man.

His voice was as ambiguous as his face. If it was a boy’s, it was on the light side, but it was deep for a girl’s.

“I have other business here,” the man said. “You’ll be safe with Master Rowan. He’ll look after you as if you were his own, and take you where you want to go.”

The boy set his lips together. Euan could see how unhappy he was, but he did not whine or beg. He turned his back and mounted the black horse, then waited for the rest of them with an air of cold disdain.

The man shook his head slightly, but did not press the issue. They were either brothers or lovers, Euan thought. No one else would wage war over matters so small.

At long last the caravan began to move. Its pace was slow, dictated by the mules and the oxen. They would be on the road for days longer than strictly necessary, but none of the hostages minded overmuch. They needed time to rest and steady their minds before they reached their destination.

Their guards’ vigilance was less strict in the caravan than it had been on the way from the border. They were allowed to move somewhat among the men of the caravan, and to carry on conversations. They used the opportunity to practice their Aurelian as well as the horsemanship they had been practicing, forcibly, since the day they were sent on this journey.