Полная версия

2021 Guide to the Night Sky

Draco

The constellation of Draco consists of a quadrilateral of stars, known as the ‘Head of Draco’ (and also the ‘Lozenge’), and a long chain of stars forming the neck and body of the dragon. To find the Head of Draco, locate the two stars Phecda and Megrez (γ and δ Ursae Majoris) in the Plough, opposite the Pointers. Extend a line from Phecda through Megrez by about eight times their separation, right across the sky below the Guards in Ursa Minor, ending at Grumium (ξ Draconis) at one corner of the quadrilateral. The brightest star, Eltanin (γ Draconis) lies farther to the south. From the head of Draco, the constellation first runs northeast to Altais (δ Draconis) and ε Draconis, then doubles back southwards before winding its way through Thuban (α Draconis) before ending at Giausar (λ Draconis) between the Pointers and Polaris.

The stars and constellations inside the circle are always above the horizon, seen from our latitude.

The Winter Constellations

The winter sky is dominated by several bright stars and distinctive constellations. The most conspicuous constellation is Orion, the main body of which has an hour-glass shape. It straddles the celestial equator and is thus visible from anywhere in the world. The three stars that form the ‘Belt’ of Orion point down towards the southeast and to Sirius (α Canis Majoris), the brightest star in the sky. Mintaka (δ Orionis), the star at the northeastern end of the Belt, farthest from Sirius, actually lies just slightly south of the celestial equator.

A line from Bellatrix (γ Orionis) at the ‘top right-hand corner’ of Orion, through Aldebaran (α Tauri), past the ‘V’ of the Hyades cluster, points to the distinctive cluster of bright blue stars known as the Pleiades, or the ‘Seven Sisters’. Aldebaran is one of the five bright stars that may sometimes be occulted (hidden) by the Moon. Another line from Bellatrix, through Betelgeuse (α Orionis), if carried right across the sky, points to the constellation of Leo, a prominent constellation in the spring sky.

Six bright stars in six different constellations: Capella (α Aurigae), Aldebaran (α Tauri), Rigel (β Orionis), Sirius (α Canis Majoris), Procyon (α Canis Minoris) and Pollux (β Gemini) form what is sometimes known as the ‘Winter Hexagon’. Pollux is accompanied to the northwest by the slightly fainter star of Castor (α Gemini), the second ‘Twin’.

In a counterpart to the famous ‘Summer Triangle’, an almost perfect equilateral triangle, the ‘Winter Triangle’, is formed by Betelgeuse (α Orionis), Sirius (α Canis Majoris) and Procyon (α Canis Minoris).

Several of the stars in this region of the sky show distinctive tints: Betelgeuse (α Orionis) is reddish, Aldebaran (α Tauri) is orange and Rigel (β Orionis) is blue-white.

The Spring Constellations

The most prominent constellation in the spring sky is the zodiacal constellation of Leo, and its brightest star, Regulus (α Leonis), which may be found by extending a line from Megrez and Phecda (δ and γ Ursae Majoris, respectively) – the two stars on the opposite side of the bowl of the Plough from the Pointers – down to the southeast. Regulus forms the ‘dot’ of the ‘backward question mark’ known as ‘the Sickle’. Regulus, like Aldebaran in Taurus is one of the bright stars that lie close to the ecliptic, and that are occasionally occulted by the Moon. The same line from Ursa Major to Regulus, if continued, leads to Alphard (α Hydrae), the brightest star in Hydra, the largest of the 88 constellations.

The shape formed by the body of Leo is sometimes known as the ‘Spring Trapezium’. At the other end of the constellation from Regulus is Denebola (β Leonis), and the line forming the back of the constellation through Denebola points to the bright star Spica (α Virginis) in the constellation of Virgo. A saying that helps to locate Spica is well-known to astronomers: ‘Arc to Arcturus and then speed on to Spica.’ This suggests following the arc of the tail of Ursa Major to Arcturus and then on to Spica. Arcturus (α Boötis) is actually the brightest star in the northern hemisphere of the sky. (Although other stars, such as Sirius, are brighter, they are all in the southern hemisphere.) Overall, the constellation of Boötes is sometimes described as ‘kite-shaped’ or ‘shaped like the letter P’.

Although Spica is the brightest star in the zodiacal constellation of Virgo, the rest of the constellation is not particularly distinct, consisting of a rough quadrilateral of moderately bright stars and some fainter lines of stars extending outwards.

The Summer Constellations

On summer nights, the three bright stars Deneb (α Cygni), Vega (α Lyrae) and Altair (α Aquilae) form the striking ‘Summer Triangle’. The constellations of Cygnus (the Swan) and Aquila (the Eagle) represent birds ‘flying’ down the length of the Milky Way. This part of the Milky Way contains the Great Rift, an elongated dark region, where the light from distant stars is obscured by intervening dust. The dark Rift is clearly visible even to the naked eye.

The most prominent stars of Cygnus are sometimes known as the ‘Northern Cross’ (as a counterpart to the ‘Southern Cross’ – the constellation of Crux – in the southern hemisphere). The central line of Cygnus through Albireo (β Cygni), extended well to the southwest, points to Sabik (η Ophiuchi) in the large, sprawling constellation of Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer) and beyond to Antares (α Scorpii) in the constellation of Scorpius. Like Cepheus, the shape of Ophiuchus somewhat resembles the gable-end of a house, and the brightest star Rasalhague (α Ophiuchi) is at the ‘apex’ of the ‘gable’.

A line from the central star of Cygnus, Sadr (γ Cygni) through δ Cygni, in the northwestern ‘wing’ points towards the Head of Draco, and is another way of locating that part of the constellation. Another line from Sadr to Vega indicates the central portion, ‘The Keystone’, of the constellation of Hercules. An arc through the same stars, in the opposite direction, points towards the constellation of Pegasus, and more specifically to the ‘Great Square of Pegasus’.

Aquila is less conspicuous than Cygnus and consists of a diamond shape of stars, representing the body and wings of the eagle, together with a rather faint star, λ Aquilae, marking the ‘head’. Lyra (the Lyre) mainly consists of Vega (α Lyrae) and a small quadrilateral of stars to its southeast. Continuation of a line from Vega through Altair indicates the zodiacal constellation of Capricornus.

The Autumn Constellations

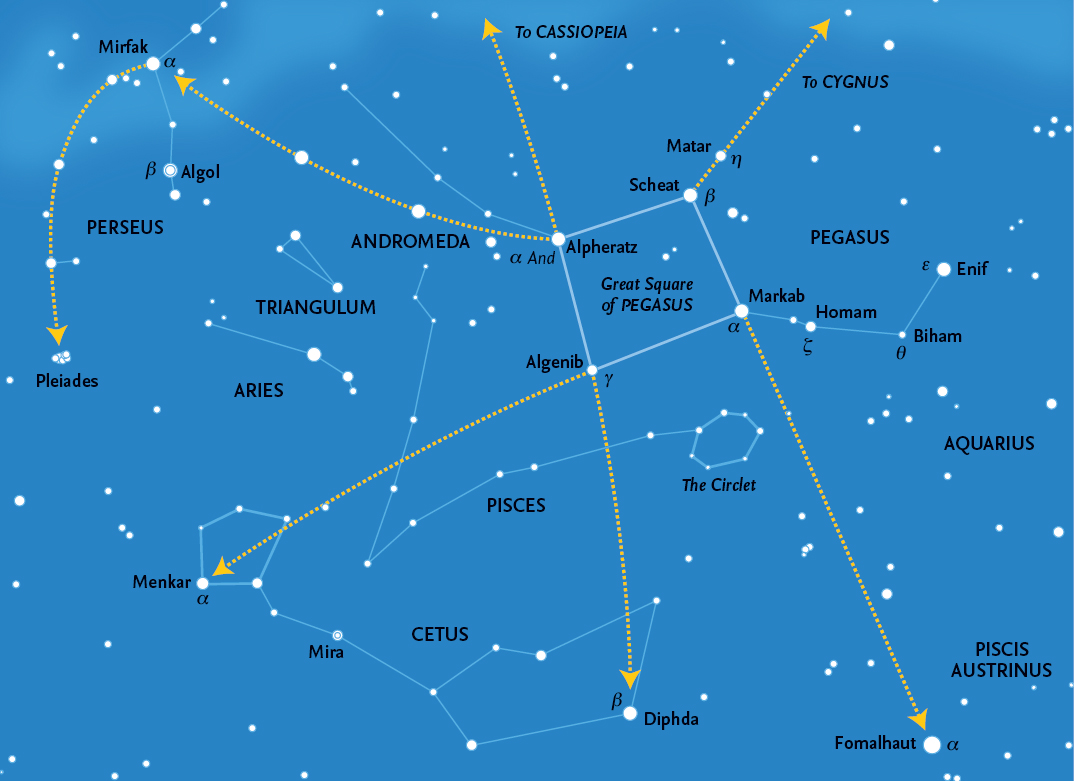

During the autumn season, the most striking feature is the ‘Great Square of Pegasus’, an almost perfect rectangle on the sky, forming the main body of the constellation of Pegasus. However, the star at the northeastern corner, Alpheratz, is actually α Andromedae, and part of the adjacent constellation of Andromeda. A line from Scheat (β Pegasi) at the northeastern corner of the Square, through Matar (η Pegasi), points in the general direction of Cygnus. A crooked line of stars leads from Markab (α Pegasi) through Homam (ζ Pegasi) and Biham (θ Pegasi) to Enif (ε Pegasi). A line from Markab through the last star in the Square, Algenib (γ Pegasi) points in the general direction of the five stars, including Menkar (α Ceti) that form the ‘tail’ of the constellation of Cetus (the Whale). A ring of seven stars lying below the southern side of the Great Square is known as ‘the Circlet’, part of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes).

Extending the line of the western side of the Great Square towards the south leads to the isolated bright star, Fomalhaut (α Piscis Austrini), in the Southern Fish. Following the line of the eastern side of the Great Square towards the north leads to Cassiopeia while, in the other direction, it points towards Diphda (β Ceti), which is actually the brightest star in Cetus.

Three bright stars leading northeast from Alpheratz form the main body of the constellation of Andromeda. Continuation of that line leads towards the constellation of Perseus and Mirfak (α Persei). Running southwards from Mirfak is a chain of stars, one of which is the famous variable star Algol (β Persei). Farther east, an arc of stars leads to the prominent cluster of the Pleiades, in the constellation of Taurus.

Between Andromeda and Cetus lie the two small constellations of Triangulum (the Triangle) and Aries (the Ram).

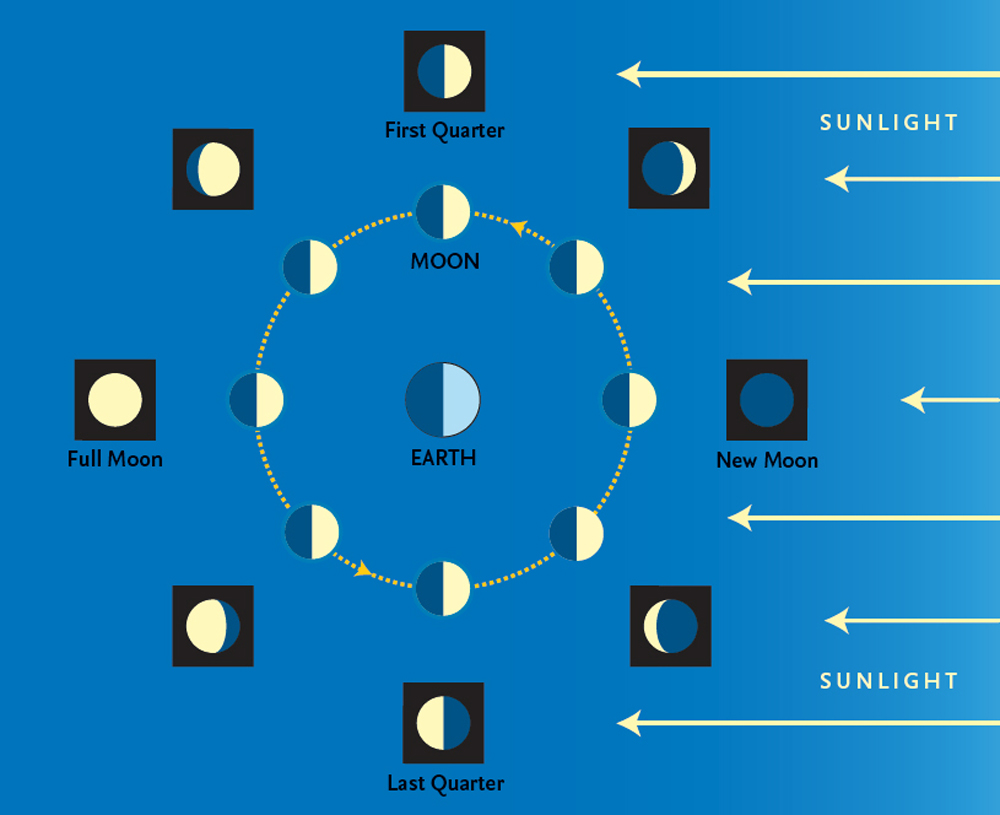

The Moon at First Quarter.

The Moon

The monthly pages include diagrams showing the phase of the Moon for every day of the month, and also indicate the day in the lunation (or age of the Moon), which begins at New Moon. Although the main features of the surface – the light highlands and the dark maria (seas) – may be seen with the naked eye, far more features may be detected with the use of binoculars or any telescope. The many craters are best seen when they are close to the terminator (the boundary between the illuminated and the non-illuminated areas of the surface), when the Sun rises or sets over any particular region of the Moon and the crater walls or central peaks cast strong shadows. Most features become difficult to see at Full Moon, although this is the best time to see the bright ray systems surrounding certain craters. Accompanying the Moon map on the following pages is a list of prominent features, including the days in the lunation when features are normally close to the terminator and thus easiest to see. A few bright features such as Linné and Proclus, visible when well illuminated, are also listed. One feature, Rupes Recta (the Straight Wall) is readily visible only when it casts a shadow with light from the east, appearing as a light line when illuminated from the opposite direction.

The dates of visibility vary slightly through the effects of libration. Because the Moon’s orbit is inclined to the Earth’s equator and also because it moves in an ellipse, the Moon appears to rock slightly from side to side (and nod up and down). Features near the limb (the edge of the Moon) may vary considerably in their location and visibility. (This is easily noticeable with Mare Crisium and the craters Tycho and Plato.) Another effect is that at crescent phases before and after New Moon, the normally non-illuminated portion of the Moon receives a certain amount of light, reflected from the Earth. This Earthshine may enable certain bright features (such as Aristarchus, Kepler and Copernicus) to be detected even though they are not illuminated by sunlight.

The Moon phases. During its orbit around the Earth we see different portions of the illuminated side of the Moon’s surface.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.