Полная версия

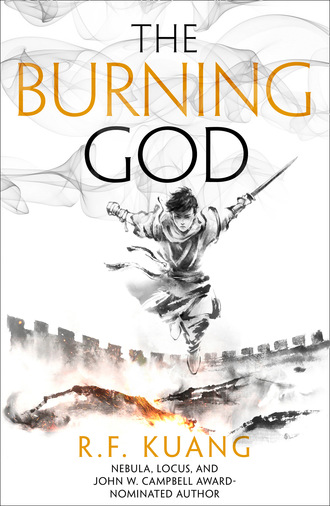

The Burning God

She squeezed her eyes shut. She imagined herself falling backward into the Phoenix’s warmth, into that distant space where nothing mattered but rage. The thin wail wavered.

Burn, she thought, shut up and burn.

CHAPTER 2

“Well done,” Kitay said.

She threw her arms around him, pulled him tight against her, and lingered in his embrace for a long while. By now she should have become used to their brief separations, but leaving him behind felt harder and harder every time.

She tried to convince herself that it wasn’t solely because Kitay was the one source of her power. That it wasn’t just because of her selfish concern that if anything happened to him, she was useless.

No, she also felt responsible for him. Guilty, rather. Kitay’s mind was stretched like a rope between her and the Phoenix, and between the rage and hatred and shame, he felt everything. He kept her safe from madness, and she subjected him to madness in return. Nothing she ever did could repay that debt.

“You’re shaking,” she said.

“I’m all right,” he said. “It’s nothing.”

“You’re lying.” Even in the dim light of dawn, Rin could see his legs were trembling. He was far from all right—he could barely stand. They had this same argument after every battle. Every time she came back and saw what she’d done to him, saw his pale, drawn face and knew that to him, it felt like torture. Every time he denied it.

She’d limit her use of flame if only he asked. He never asked.

“I’ll be fine,” he amended gently. He nodded over her shoulder. “And you’re drawing a bit of attention.”

Rin turned and saw Khudla’s survivors.

This had happened often enough that she knew what to expect.

First they wandered forward in little, tentative clumps. Curious whispering, terrified pointing. Then, when they realized that this new army was not Mugenese but Nikara, not Militia but something new entirely, and that Rin’s soldiers were not here to replace their oppressors, they grew braver.

Is she the Speerly? they asked. Are you the Speerly?

Are you one of us?

And then the whispers grew louder as the crowd swelled, bodies coalescing around her. They spoke her name, her race, her god. Her legend had already spread to this place; she could hear it rippling through the field.

They reached out to touch her.

Rin’s chest constricted. Her breathing quickened; her throat felt blocked.

Kitay’s hand tightened around her arm. He didn’t have to ask what was wrong; he knew.

“Are you—” he began.

“It’s fine,” she murmured. “It’s fine.”

These hands were not the enemy’s. She was not in danger. She knew that, but her body didn’t. She took a deep breath and composed her face. She had to play the part—had to look like not the scared girl she’d once been or the tired soldier that she was, but the leader they needed.

“You’re free,” she told them. Her voice quivered with exhaustion; she cleared her throat. “Go.”

A hush ran through the crowd when they saw that she spoke their language—not the abrasive Nikara of the north, but the slow, rolling dialect of the south.

They still regarded her with a kind of awed terror. But she knew this was the kind of fear that turned into love.

Rin raised her voice and spoke, this time without a tremor. “Go tell your families that they’ve been saved. Tell them the Mugenese can’t harm you any longer. And when they ask who broke your shackles, tell them the Southern Coalition is marching across the Empire with the Phoenix at its fore. Tell them we’re taking back our home.”

As the sun climbed through the sky, Rin commenced Khudla’s liberation.

This was supposed to be the fun part. It was supposed to feel good, telling grateful villagers that their erstwhile occupiers were smoldering piles of ash.

But Rin dreaded liberation. Combing through a half-destroyed village to find survivors only meant yet another survey of the extent of Federation cruelty. She’d rather face the battlefield again than confront that suffering. It didn’t matter that she’d already seen the worst at Golyn Niis, that she’d witnessed the worst things one could do to a human body dozens of times over. It never got easier.

She’d learned by now that the Mugenese implemented the same three measures every time they occupied a city, three directives so clean and textbook that she could have written a full treatise on how to subdue a population herself.

First, the Mugenese rounded up every Nikara man who resisted their occupation, marched them to the killing fields, and either shot or beheaded them. Beheading was more common; arrows were valuable resources and couldn’t always be retrieved intact. They didn’t kill all the local men, just those who had threatened to make trouble. They needed laborers.

Second, the Mugenese either repurposed or stripped away the village infrastructure. Anything sturdy they turned into soldiers’ barracks, and anything flimsy they tore apart for firewood. When the loose wood was gone, they scoured the homes for furniture, blankets, valuables, and ceramics with which to furnish their barracks. They were very efficient at turning villages into empty shells. Rin often found liberated villagers crowded in pigsties, cramped together knee to knee just to keep warm.

Third, the Mugenese co-opted the local leadership. After all, what did you do when you didn’t speak the local language? When you didn’t grasp the nuances of regional politics? You didn’t supplant the existing leadership structure—that would result in chaos. You grafted yourself onto it. You got the local bullies to do your dirty work for you.

Rin hated the Nikara collaborators. Their crimes, to her, seemed almost worse than those of the Federation. The Mugenese were at least targeting the enemy race—a natural instinct in wartime. But collaborators helped the Mugenese murder, mutilate, and violate their own kind. That was inconceivable. Unforgivable.

Rin and Kitay were always split on how to handle the captured collaborators. Kitay begged for lenience. They were desperate, he argued. They were trying to save their own skins. They might have saved some villagers’ skins. Sometimes compliance saves you pain. Compliance might have saved us at Golyn Niis.

Bullshit, Rin retorted. Compliance was cowardice. She had no respect for anyone who would rather die than fight. She wanted the collaborators to burn.

But the matter was out of their hands. The villagers invariably settled things themselves. Sometime in the next week, if not in the next day, they would drag the collaborators into the middle of the square, extract their confessions, and then flay, whip, beat, or stone them. Rin never had to intervene. The south delivered its own justice. The catharsis of violence hadn’t happened yet in Khudla—it was too early in the morning for a public execution, and the villagers were too starved and exhausted to form a mob—but Rin knew that soon enough, she would hear screaming.

Meanwhile, she had survivors to find. She was looking for prisoners. The Federation always took captives—political dissidents, soldiers too willful to control but too useful to let die, or hostages they hoped might dissuade their incoming attackers. Sometimes the bodies were freshly dead—either from one last act of vengeance by desperate Mugenese soldiers under siege, or suffocated by smoke from Rin’s flames.

More often, however, she found them alive. You couldn’t kill hostages if you ever meant to use them.

Kitay led soldiers to search in the eastern edge of the village through the Mugenese-occupied buildings that had escaped the brunt of the destruction. He had a particular talent for finding survivors. He’d once hidden for weeks behind a bricked-up wall at Golyn Niis, cringing and hugging his knees while Federation soldiers dragged Nikara soldiers from their hiding spots and shot them on the streets. He knew how to look for the signs—tarps or stacked debris that seemed out of place, faint footprints in the dust, echoes of shallow breathing in frightened silence.

Rin alone took on the burned wreckage.

She dreaded this task: pulling charred boards aside to find bodies broken and bleeding but still breathing. Too many times they were beyond saving. Half the time she’d caused the destruction herself. Once flames started burning, they were difficult to put out.

Still, she had to try.

“Is anyone here?” she called repeatedly. “Make a noise. Any noise. I’m listening.”

She went through every cellar, every abandoned lot and well; shouted out for survivors many times and made sure she listened hard to the echoing silence. It would be a horrible fate to be chained up, slowly starving or suffocating to death because your village had been liberated but the survivors forgot about you. Her eyes watered as she stumbled through a smoky grain cellar. She doubted she’d find anything—already she’d stumbled over two corpses—but she waited a moment before she left. Just in case.

Her patience rewarded her.

“In the back,” called a voice.

Rin pulled a flame into her hand, illuminating the far wall of the cellar. She couldn’t see anything but empty grain sacks. She stepped closer.

“Who are you?” she demanded.

“Souji.” She heard the clink of chains. “Likely the man you’re looking for.”

She decided she wasn’t dealing with an ambush. She knew that flat-tongued, rustic accent. The best Mugenese spies couldn’t imitate it; they’d all trained only to speak the curt Sinegardian dialect.

She crossed to the other end of the cellar, stopped, and amplified her torchlight.

Her first goal at Khudla had been liberation. Her second goal was to locate Yang Souji, the famed rebel leader and local hero who had until recently been fending off the Mugenese in southern Monkey Province. The closer she’d marched to Khudla, the more myths and rumors she’d heard about him. Yang Souji had eyes that could see for ten thousand miles. He could speak to animals; he knew when the Mugenese were coming because the birds always warned him. His skin was invulnerable to all kinds of metal—swords, arrowheads, axes, spears.

The man chained to the floor was none of those things. He looked surprisingly young—he couldn’t be more than a few years older than she was. A scraggly beard had sprouted over his neck and chin, some indication of how long he’d been chained up, but he sat up straight with his shoulders rolled back, and his eyes shone bright in the firelight.

Despite herself, Rin found him surprisingly handsome.

“So you’re the Speerly,” he said. “I thought you’d be taller.”

“And I thought you’d be older,” she said.

“Then we’re both a disappointment.” He jangled his chains at her. “Took you long enough. Did you really need all night?”

She knelt down and began working at the locks. “Not even a thank-you?”

“You’re going to do that one-handed?” he asked skeptically.

She fumbled with the pin. “Look, if you’re going to—”

“Give me that.” He plucked the pin from her fingers. “Just hold the lock up where I can see it and give me some light—there you go.”

As she watched him work at the lock with remarkable dexterity, she couldn’t help but feel a flicker of jealousy. It still stung, how the simplest things—picking locks, getting dressed, filling her canteen—had become so damnably difficult overnight.

She’d lost her hand to such a stupid turn of events. If they’d only had a key back then. If they’d just been able to steal a motherfucking key.

Her stump itched. She clenched her teeth and willed herself not to scratch it.

Souji undid the lock in less than a minute. He shook his hands free and sighed, cradling his wrists. He bent over toward the chains around his ankles. “That’s better. Can you give me some more light?”

She moved the flame closer to the lock, careful not to singe his skin.

She noticed the middle finger on his right hand was missing its top joint. It didn’t look like an accident—the middle finger on his left hand was missing a joint as well.

“What’s wrong with your hands?” she asked.

“My mother’s first two children died in infancy,” he explained. “She thought that the gods were stealing them because they were so lovely. So when I entered the world she gnawed the first joint off both my middle fingers.” He wiggled his left hand at her. “Made me a bit less attractive.”

Rin snorted. “The gods don’t want fingers.”

“So what do they want?”

“Pain,” she said. “Pain, and your sanity.”

Souji popped the lock, shook the chains away, and clambered to his feet. “I suppose you would know.”

After all likely survivors had been rescued from the wreckage, Rin’s troops fell on the battlefield like vultures.

The first time the newly minted soldiers of the Southern Coalition had scavenged for supplies in the wake of a battle, they’d been reluctant to touch the corpses. They’d been superstitious, scared of angering vengeful ghosts of the unburied dead who couldn’t return home. Now they raided bodies with hardened disregard, stripping them of anything of value. They looked for weapons, leather, clean linens—Mugenese uniforms were blue, but could be easily dyed—and, prized above all, shoes.

The Southern Coalition’s troops suffered terribly from shoddy footwear. They fought in straw sandals, and cotton if they could obtain it, but those cotton shoes were more like slippers, sewn weeks before the battle by wives, mothers, and sisters. Most were fighting in footwear of plaited straw that broke midmarch, fell apart in sticky mud, and offered no protection against the cold.

The Mugenese, however, had sailed over the Nariin Sea wearing leather boots—fine, solid, warm, and waterproof. Rin’s soldiers had become very adept at untying the laces, yanking boots off stiffening feet, and tossing them into wheelbarrows to be redistributed later according to size.

While Rin’s soldiers combed through the fields, Souji led her toward the former village headman’s office, which the Mugenese had repurposed into a headquarters. He provided running commentary on the ruins as they walked, like a disgruntled host apologetic that his home had been found in such a mess.

“It looked loads better than this months ago. Khudla’s a nice village—had some lovely historic architecture, until they tore down everything for firewood. And we made those barricades,” he said somewhat sulkily, pointing to the sandbags around the headquarters. “They just stole them.”

For a simple village’s defenses, Souji’s barricades had been surprisingly well constructed. He’d organized pillboxes the way she would have done it—wooden stakes driven into the ground to provide a lattice framework for layers of sandbags. She’d been taught that method at Sinegard. These defenses, Rin realized, had been built according to Militia guidelines.

“Then how did they get through in the end?” she asked.

Souji blinked at her as if she were an idiot. “They had gas.”

So Officer Shen was right. Rin stifled a shudder, imagining the impact of the noxious yellow fumes on unsuspecting civilians. “How much?”

“Just one canister,” Souji said. “I think they’d been hoarding it, because they didn’t use it when they first came. Waited until the third day of fighting, when they had us all barricaded into one place, and then they popped it over the wall. We fell apart pretty quickly after that.”

They reached the headquarters. Souji tried the door. It swung open without trouble; no one was left to lock it from the inside.

Food littered the table of the central conference room. Souji picked a wheat bun off its place, tore off a bite, then spat it back out. “Disgusting.”

“What, too stale for you?”

“No. It’s got too much salt. Gross.” Souji tossed the wheat bun back onto the table. “Salt doesn’t belong in buns.”

Rin’s mouth watered. “They have salt?”

She hadn’t tasted salt in weeks. Most salt in the Empire was imported from the basins of Dog Province, but those trade networks had completely broken down during Vaisra’s civil war. Out in the arid eastern Monkey Province, Rin’s army had been subsisting on the blandest rice gruel and boiled vegetables. There were rumored to be a few jars of fermented soy paste hidden in the kitchens at Ruijin, but if they existed, Rin had never seen nor tasted them.

“We had salt,” Souji corrected. He bent over to examine the contents of a barrel. “Looks like they’ve eaten through most of it. There’s only a handful left.”

“Take that back to the public kitchen. We’ll treat everyone.” Rin leaned over the commander’s desk. Documents were strewn all over its surface. Rin found troop numbers, food ration records, and letters written in a scrawled, messy script that she could barely read. Here and there she could make out a few words. Wife. Home. Emperor.

She collected them into a neat pile. She and Kitay would pore over them later, see if they bore any meaningful news about the Mugenese. But they were likely months old, like the other correspondence they’d found. Every dead Mugenese general kept letters from the mainland on their desk, as if rereading those Mugini characters could maintain their connection to a motherland they must have known was gone.

“They were reading Sunzi?” Rin picked up the slim text—a Nikara edition, not a translation. “And the Bodhidharma? Where’d they get these?”

“Those were mine. Stole them out of the Sinegard library way back in the day.” Souji plucked the booklet from her hand. “I take them with me everywhere I go. Those bastards wouldn’t have been able to make head or tail of them.”

Rin glanced at him, surprised. “You’re a Sinegard graduate?”

“Not a graduate. I was there for two years. Then the famine struck, so I went home. Jima didn’t let me back in when I returned. But I still needed a paycheck, so I enlisted in the Militia.”

So he’d passed the Keju. That was rare for someone from his background—Rin should know. She regarded Souji with a newfound respect. “Why wouldn’t they?”

“Because they thought that if I left once, then I’d do it again. That I’d always prioritize my family over my military career. Guess they were right. I would have left the ranks the moment we got wind of the Mugenese invasion.”

“And what about now?”

“Whole family’s dead.” His voice was flat. “Died this past year.”

“I’m sorry. Was it the Federation?”

“No. The flood.” Souji jerked out a shrug. “We’re usually pretty good at seeing floods coming. Not hard to read the weather if you know what you’re doing. But not this time. This was man-made.”

“The Empress broke the dams,” Rin said automatically. Chaghan and Qara felt like such a distant memory that she could speak this lie without struggle. Best that Souji didn’t know that the Cike, her old regiment, had deliberately caused the flood that killed his family.

“Broke the dams to stem an enemy that she’d invited in herself.” Souji’s voice turned bitter. “I know. I’d learned to swim at Sinegard. They hadn’t. There’s nothing where my village used to be.”

Rin felt a stab of guilt. She did her best to ignore it. She shouldn’t have to shoulder the blame for that particular atrocity. That flood had been the fault of the twins, an act of environmental warfare to slow the Federation’s progress inland.

Who could say if it had worked, or if it had even mattered? What was done was done. The only way to live with your transgressions, Rin had learned, was to lock them away in your mind and leave them in the abyss.

“Why can’t you just blow them up?” Souji asked abruptly.

She blinked at him. “What?”

“When you ended the war. When the longbow island went up in smoke. What’s stopping you from doing that again in the south?”

“Prudence,” she said. “If I burn them, I burn everyone. Fire on that scale doesn’t discriminate. A massive genocide on our own territory would—”

“We don’t need a massive genocide. Just a little one would do.”

“You don’t know what you’re asking for.” She turned away; she didn’t want to meet his eyes. “Even the little fires hurt people they shouldn’t.”

She’d grown tired of this question. That was what everyone wanted to know—why she couldn’t simply snap her fingers and incinerate the Mugenese camp like she’d done to their entire island. If she’d finished off a nation once, why couldn’t she do it again? Why couldn’t she end this whole war in seconds? Wasn’t that so obviously the next move?

She wished she could do it. There were times when she wanted so badly to send walls of flame roaring across the entire south, clearing out the Mugenese the way one might raze a field of blighted crops, with no regard for the collateral damage.

But every time that desire surged within her, she ran up against the same pulsing black venom that clouded her mind—Su Daji’s parting gift, the Seal that cut her off from direct access to the Pantheon.

Maybe it was a blessing that her mind remained blocked by the Seal, that she was forced to use Kitay as a conduit for her power. Kitay kept her sane. Stable. He let her call the fire, but only in targeted, limited bursts.

Without Kitay, Rin was terrified of what she might do.

“If I were you,” Souji said, “I would have gotten rid of them all. One single blaze, and the south would be clean. Fuck prudence.”

She shot him a wry look. “Then you’d be dead, too.”

“Just as well,” he said, and sounded like he meant it.

Rin felt as if eternity had passed by the time the sun set. Twenty-four hours ago, she had led troops into battle for the first time. That afternoon, she’d liberated a village. Now her wrist throbbed, her knees shook, and a headache pounded behind her eyes.

She could not silence the memory of that scream in the temple. She needed to silence it.

Back in her tent, she dug a packet of opium out from the bottom of her traveling satchel and pressed a nugget into a pipe.

“Do you have to?” Kitay asked. It wasn’t really a question. They’d had this argument a thousand times, and every time arrived at the same lack of resolution. He just felt obligated to express his displeasure. By now they were simply going through the motions.

“It’s not your business,” she said.

“You need to sleep. You’ve been up nearly forty-eight hours.”

“I’ll sleep after this. I can’t relax without it.”

“It smells awful.”

“So go sleep somewhere else.”

Silently Kitay stood up and walked out of the tent.

Rin didn’t watch him go. She lifted the pipe to her mouth, lit the bowl with her fingers, and breathed in deep. Then she curled over on her side and drew her knees into her chest.

In seconds she saw the Seal—a live, pulsing thing, reeking so strongly of the Vipress’s venom that Su Daji might have been standing in the tent right next to her. She used to curse the Seal, used to barrel pointlessly against the immutable barrier of venom that wouldn’t leave her mind.

But she’d since found a better use for it.

Rin drifted toward the glistening characters. The Seal tilted toward her, opened, and swallowed her. There was a brief moment of blinding, terrifying darkness, and then she was in a dark room with no doors or windows.

Daji’s poison was composed of desire—the things she would kill for, the things she missed so badly she wanted to die.

Altan materialized on cue.

Rin used to be so afraid of him. She’d felt a little thrill of fear every time she’d looked at him, and she’d liked it. When he was alive, she’d never known if he was going to caress or throttle her. The first time she’d seen him inside the Seal, he’d nearly convinced her to follow him into oblivion. But now she kept him leashed in her mind, firmly under control, and he spoke only when she wanted him to.

Still the fear remained. She couldn’t help it, nor did she want to.