Полная версия

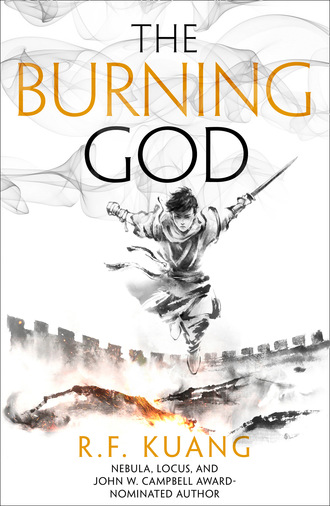

The Burning God

Later that afternoon, as Rin headed to the fields to supervise basic training, she was accosted by a wizened old woman dragging two skinny girls along by their wrists.

“We heard you were taking girls,” she said. “Will they do?”

Rin was so startled by her pushy irreverence that rather than directing the woman to the enlistment stand, she paused and looked. She was puzzled by what she saw. The girls were thin and scrawny, certainly no older than fifteen, and they cowered behind the old woman as if terrified of being seen. They couldn’t possibly be volunteers—every other woman who had enlisted in the Southern Army had done so proudly and of her own volition.

“You’re taking girls,” the old woman prompted.

Rin hesitated. “Yes, but—”

“They’re sisters. You can have them for two silvers.”

Rin blinked. “Pardon?”

“One silver?” the woman suggested impatiently.

“I’m not paying you anything.” Rin’s brow furrowed. “That’s not what—”

“They’re good girls,” said the woman. “Quick. Obedient. And neither are virgins—”

“Virgins?” Rin repeated. “What do you think we’re doing here?”

The woman looked at her as if she were mad. “They said you were taking girls. For the army.”

Then the pieces fell together. Rin’s gut twisted. “We aren’t hiring prostitutes.”

The woman was undaunted. “One silver.”

“Get out of here,” Rin snapped. “Or I’ll have you thrown in jail.”

The woman spat a gob of saliva at Rin’s feet and stormed off, tugging the girls behind her.

“Hold it,” Rin said. “Leave them.”

The woman paused, looking for a moment like she might protest. So Rin let a stream of fire, ever so delicate, slip through her fingers and dance around her wrist. “I wasn’t asking.”

Hastily, the woman left without another word.

Rin turned to the girls. They had barely moved this whole time. Neither would meet her eyes. They stood still, arms hanging loose by their sides, heads lowered deferentially like house servants waiting for commands.

Rin had the oddest temptation to pinch their arms, check their muscles, turn up their chins, and open their mouths to see if their teeth were good. What is wrong with me?

She asked, for want of anything better to say, “Do you want to be soldiers?”

The older girl shot Rin a fleeting glance, then gave a dull shrug. The other didn’t react at all; her eyes remained fixed on an empty patch of air before her.

Rin tried something else. “What are your names?”

“Pipaji,” said the older girl.

The younger girl’s eyes dropped to the ground.

“What’s wrong with her?” Rin asked.

“She doesn’t speak,” snapped Pipaji. Rin saw a sudden flash of anger in her eyes—a sharp defensiveness, and she understood then that Pipaji had spent her entire life shielding her sister from other people.

“I understand,” Rin said. “You speak for her. What’s her name?”

The hostility eased somewhat from Pipaji’s face. “Jiuto.”

“Jiuto and Pipaji,” Rin said. “Do you have a family name?”

Silence.

“Where are you from?”

Pipaji gave her a sullen look. “Not here.”

“I see. They took your home, too, huh?”

Pipaji gave a listless shrug, as if she found this question incredibly stupid.

“Listen,” Rin said. Her patience was running out. She wanted to be on the field with her troops, not coaxing words from sullen little girls. “I haven’t got time for this. You’re free of that woman, so you can do whatever you like. You can join this army if you want—”

“Do we get food?” Pipaji interrupted.

“Yes. Twice a day.”

Pipaji considered this for a moment, then nodded. “Okay.”

Her tone made it clear she had no further questions. Rin watched them both for a moment, then shrugged and pointed. “Good. Barracks are over there.”

CHAPTER 7

Two weeks later they reached Tikany.

Rin had been prepared to fight for her hometown. But when her troops approached Tikany’s earthen walls, the fields were quiet. The trenches lay empty; the gates hung wide open, with no sentries in sight. This wasn’t the deceptive stillness of a waiting ambush but the listless silence of a place abandoned. Whatever Mugenese troops had once terrorized Tikany had already fled. Rin passed completely unobstructed through the northern gates into a place she hadn’t seen since she’d left it nearly five years ago.

She didn’t recognize it.

Not because she’d forgotten. As much as she’d once wanted to, she’d never erase the texture of this place from her mind—not the clouds of red dust that blew through the streets on windy days, covering everything with a fine sheen of crimson; not the abandoned shrines and temples around every corner, remnants of more superstitious days; not the rickety wooden buildings emerging from dirt like angry, resilient scars. She knew Tikany’s streets like she knew the back of her hand; knew its alleys, hidden tunnels, and opium drop-off sites; knew the best hiding corners wherein to take refuge when Auntie Fang’s temper bubbled over into violence.

But Tikany had changed. The whole place felt empty, hollowed, like someone had gouged its intestines out with a knife and devoured them, leaving behind a fragile, traumatized shell. Tikany had never been one of the Empire’s great cities, but it had held life. It had been, like so many of the southern cities, a locus of small autonomy, carved defiantly into the hard soil.

The Federation had turned it into a city of the dead.

Most of the ramshackle buildings were gone, long since burned down or dismantled. The Mugenese had turned what was left into a spare military camp. The library, the outdoor opera stage, and schoolhouse—the only places in Tikany that had ever brought Rin any happiness—were skeletal structures that showed signs of deliberate deconstruction. Rin guessed the Mugenese had stripped down their walls for firewood.

In the pleasure district, the whorehouses alone remained standing.

“Take twelve troops—women, if possible—and scour every one of those buildings for survivors,” Rin told the closest officer. “Hurry.”

She knew by now what they would likely find. She knew she should have gone herself. She wasn’t brave enough for it.

She kept walking. Closer to the township center, near the magistrate’s hall and public ceremonies office, she found evidence of the public executions. Stage floorboards painted brown with months-old stains. Whips tossed onto careless piles under the spot where once, a lifetime ago, she’d read her Keju test score and realized she was going to Sinegard.

What she didn’t see were corpses. In Golyn Niis, they’d been stacked up on every street corner. Tikany’s streets were empty.

But that made sense. When your goal was occupation, you always cleaned up your corpses. Otherwise they stank.

“Great Tortoise.” Souji whistled under his breath as he strode beside her, hands in his pockets, peering about the devastation like a child perusing a holiday market. “They really did a number on this place.”

“Shut up,” Rin said.

“What’s the matter? Did they tear down your favorite teahouse?”

“I said shut up.”

She hated the thought of crying in front of him, yet she could barely breathe for the weight crushing her chest. Her head felt terribly light; her temples throbbed. She dug her nails into her palm to ward off the tears.

She’d seen large-scale devastation like this only once before, and it had almost broken her. But this was worse than Golyn Niis, because at least in Golyn Niis, most everyone was dead. She would almost have rather seen corpses than the survivors she saw now, crawling out from whatever safe houses remained standing, blinking at her with the dazed confusion of animals who had spent too long living in the dark.

“Are they gone?” they asked her. “Are we freed?”

“You’re freed,” she said. “They’re gone. Forever.”

They registered these words with fearful, doubtful looks, as if they expected the Mugenese to return any moment and smite them for their temerity. Then they grew braver. More and more of them emerged from huts, shacks, and hiding holes, more than Rin had dared hope remained alive. Whispers arced through the ghost town, and gradually the survivors began to fill the square, crowding around the soldiers, homing in on Rin.

“Are you …?” they asked.

“I am,” she said. She let them touch her so that they knew she was real. She let them see her flames, spiraling high in delicate patterns, silently conveying the words she couldn’t bring herself to say out loud.

It’s me. I’m back. I’m sorry.

“They need to wash,” Kitay said. “Almost everyone here’s got a lice problem; we need to contain it before it spreads to our troops. And they need a good meal, we should get the rations in order—”

“Can you handle it?” she asked. Her voice rang oddly in her ears when she spoke, as if coming from the other side of a thick wooden door. “I want—I need to keep walking.”

He touched her arm. “Rin—”

“I’m all right,” she said.

“You don’t have to do this alone.”

“But I do. You can’t understand.” She stepped away from him. Kitay knew every part of her soul, but he couldn’t share this with her. This was about roots, about dirt. He wasn’t from here; he couldn’t know how it felt. “You—you take care of the survivors. Let me go. Please.”

He squeezed her hand and nodded. “Just be careful.”

Rin broke away from the crowd, disappeared down a side alley while no one was watching, and then walked alone across town to her old neighborhood.

She didn’t bother going to the Fang residence. There was nothing for her there. She knew Uncle Fang was dead. She knew Auntie Fang and Kesegi had most likely died in Arlong. And aside from Kesegi, her memories of that house contained nothing but misery.

She went straight to Tutor Feyrik’s house.

His quarters were empty. She couldn’t find a single trace of him in any of the bare rooms; he might never have lived there at all. The books were gone, every last one. Even the bookshelves were missing. All that remained was a little stool, which she suspected the Mugenese had left alone because it was carved from stone and not wood.

She remembered that stool. She’d perched there so many nights as a child, listening to Tutor Feyrik talk about places she never thought she would see. She’d sat there the night before the exam, sobbing into her hands while he gently patted her shoulders and murmured that she’d be all right. A girl like you? You’ll always be all right.

He might still be alive. He might have fled early, at the first warnings of danger; he might be in one of the refugee camps up north. If she tried hard enough, she could maintain the delusion that he was somewhere out there, safe and happy, simply out of her orbit. She tried to find comfort in that thought, but the uncertainty of not knowing, perhaps never knowing, only hurt more.

She tasted salt on her lips, and realized her face was wet with tears.

Abruptly, violently, she wiped them away.

Why do you need to find him? She heard the question in Altan’s voice. Why does it fucking matter?

She’d hardly thought about Tutor Feyrik in years. She’d cut him out of her mind the same way she’d alienated herself from her sixteen years in Tikany, a snakeskin shed so she could reinvent herself from war orphan to student and soldier. She clung to his memory now out of some pathetic, cowardly nostalgia. He was only a relic—a reminder from an easier time when she was a little girl trying to memorize the Classics, and he was a kind teacher who’d shown her her only way out.

She was searching for a life she’d never have again. And Rin knew far too well by now that nostalgia could kill her.

“Find anything?” Kitay asked when she returned.

“No,” she said. “There’s nothing here.”

Rin chose to make her headquarters in the Mugenese general’s complex, partly because she felt like it was her right as liberator and partly because it was the safest place in the encampment. Before they moved in, she and Souji scoured each room, checking for any lurking assassins.

They encountered nothing but messy rooms still littered with dirty dishes, uniforms, and spare weapons. It was like the Mugenese had vanished into thin air, leaving all their belongings behind. Even the main office looked as if the general had simply stepped into the next room for a cup of tea.

Rin rooted through the general’s desk, pulling out stacks of memos, maps, and letters. In one drawer she found sheaves of paper, all charcoal sketches of the same woman. This general had apparently considered himself an artist. The sketches weren’t half bad—the general had rather painstakingly tried to capture his lover’s eyes, to the neglect of other anatomical accuracies. The same Mugenese characters accompanied each sketch—hudie, meaning “butterfly” in Nikara; she’d forgotten its Mugenese pronunciation. It was likely not a proper name but an endearment.

He was lonely, she thought. How had he felt when he learned the fate of the longbow island? When he learned that no ships were ever sailing back across the Nariin Sea?

She found a note written on a folded sheet of paper wedged in between the last two sketches. The Mugenese script was not so different from Nikara—it borrowed heavily from Nikara characters, though their pronunciations were entirely different—but it took her several minutes of parsing through messy, scrawled ink to decipher what it said.

If it means I have a traitorous heart then yes, I wish our Emperor had not summoned you for duty, for he has ripped you from my arms.

The entirety of the eastern continent—no, the riches of this universe—means nothing to me in your absence.

I pray every day for the seas to bring your return.

Your butterfly.

It was an extract torn out of a longer letter. Rin couldn’t find the rest.

She felt oddly guilty as she leafed through the general’s things. Absurdly enough, she felt like an intruder. She’d spent so much time figuring out how to kill the Mugenese that the very idea that they could be people, with private lives and loves and hopes and dreams, made her feel vaguely nauseated.

“Look at those walls,” Souji said.

Rin followed his gaze. The general had kept a detailed wall calendar, filled in neat, tiny handwriting. It was far more legible than the letter. She flipped to the very first page. “They arrived here just three months ago.”

“That’s just when they started keeping the calendar,” Souji said. “Trust me, they’ve been in the south far longer than that.”

His unspoken accusation lingered in the air between them. Three months ago she could have come south. She could have stopped this.

Rin had long since accepted that charge. She knew this was her fault. She could have taken the Empress’s hand that day in Lusan, could have killed Vaisra’s rebellion in the cradle and led her troops straight down south. But instead she’d played at revolution, and all that won her was a scar snaking across her back and an aching stump where her hand should have been.

She hated how nakedly transparent Vaisra’s strategy had been from the start, and hated herself more for failing to see it. In retrospect it was so clear why the south had to burn, why Vaisra had withheld his aid even when the southern warlords came begging at his feet.

He could have easily stopped those massacres. He’d known the Hesperian fleet was coming to his aid; he could have dispatched half his army to answer the pleas of a dying nation. He’d deliberately crippled the south instead. He didn’t have to grapple with the southern Warlords for political authority if he just let the Mugenese do his dirty work for him. And then, when the smoke cleared, when the Empire lay in fractured shambles, he would have marched in with the Republican Army and burned out the Mugenese with dirigibles and arquebuses. By then southern autonomy would have seemed laughable—whatever survivors remained would have fallen on their knees and worshipped him as their savior.

What if he had told you? Altan—Rin’s hallucination of Altan—had asked her once. What if he’d made you fully complicit? Would you have switched your allegiance?

Rin didn’t know. She had despised the southerners back then. She’d hated her own people, had hated them the moment she saw them in the camps. She’d hated their darkness, their flat-tongued rural accents and fearful, dull-eyed stares. It was so easy to mistake sheer terror for stupidity, and she’d been desperate to think of them as stupid because she knew she wasn’t stupid, and she needed any reason to set herself apart.

Back then her self-loathing had run so deep that if Vaisra had simply told her every part of his plan, she might have taken his evil for brilliance and laughed. If he hadn’t traded her away, she might never have left his side.

Anger coiled in her gut. She tore the calendar down from the wall and crushed it in her fingers.

“I was a fool for Vaisra,” she said. “I shouldn’t have counted on his virtue. But he didn’t count on my survival.”

Once they’d deemed the general’s complex safe as a home base, Rin walked across town to the whorehouses. She didn’t want to; she was hungry and exhausted, her eyes and throat felt sore from suppressed tears, and all she wanted to do was curl up in a corner with her pipe.

But she was General Fang the Speerly, and she owed this to the survivors.

Venka was already there. She’d begun the difficult work of marshaling the women from the whorehouses. Puddles and overturned buckets covered the cold stone floors where the women had showered, next to thick, dark piles of lice-ridden locks shorn from newly bald heads.

Venka stood now at the center of the square courtyard, hands clasped behind her back like a drill sergeant. The women clustered around her in a sullen circle, blankets clutched around their skinny shoulders, their eyes dull and unfocused.

“You have to eat,” Venka said. “I’m not leaving you alone until I see you swallow.”

“I can’t.” The girl in front of Venka could have been anywhere from thirteen to thirty—her skin was stretched so tight over her fragile, birdlike bones that Rin couldn’t tell.

Venka grabbed the girl’s shoulder with one hand; with the other, she held a steamed bun up so close to the girl’s face that Rin thought she might start mashing it into her lips. “Eat.”

The girl pressed her mouth shut and squirmed in Venka’s grasp, whimpering.

“What’s wrong with you?” Venka shouted. “Eat! Take care of yourself!”

The girl wriggled free and backed away, eyes scrunched up in tears, shoulders hunched as if she expected a beating.

“Venka!” Rin hurried forward and pulled Venka back by the wrist. “What are you doing?”

“What the fuck do you think?” Venka’s cheeks were chalk-pale with fury. “Everyone else has eaten, but this little bitch thinks she’s too good for her food—”

One of the other women put an arm around the girl. “She’s still in shock. Let her be.”

“Shut up.” Venka shot the girl a scathing glare. “Do you want to die?”

After a long pause, the girl gave a timid shake of her head.

“So eat.” Venka flung the bun at her. It bounced off her chest and landed on the dirt. “Right now you’re the luckiest fucking girl in the world. You’re alive. You have food. You’re saved from the brink of starvation. All you have to do is put that bun in your fucking mouth.”

The girl began to cry.

“Stop that,” Venka ordered. “Don’t be pathetic.”

“You don’t understand,” choked the girl. “I don’t—you can’t—”

“I do understand,” Venka said flatly. “Same thing happened to me at Golyn Niis.”

The girl lifted her eyes. “Then you’re a whore, too. And we should both be dead.”

Venka drew her arm back and slapped the girl hard across the face.

“Venka, stop.” Rin seized Venka’s arm and pulled her out of the courtyard. Venka didn’t resist; rather, she stumbled along willingly as if in a daze.

She wasn’t angry, Rin realized. If anything, Venka seemed about to collapse.

This wasn’t about the food.

Rin knew, deep down, that Venka hadn’t turned her back on her home province and joined the Southern Coalition—a rebellion formed of people with skin several shades darker than hers—out of any real loyalty to their cause. She’d done it because of what had happened at Golyn Niis. Because the Dragon Warlord Yin Vaisra had knowingly let those atrocities at Golyn Niis happen, had let them happen across the entire south, and hadn’t lifted a finger to stop them.

Venka had taken it upon herself to fight those battles. But as she and Rin had both discovered, the battles were easy. Destroying was easy. The hard part was the aftermath.

“Are you all right?” Rin asked quietly.

Venka’s voice trembled. “I’m just trying to make this easier.”

“I know,” Rin said. “But not everyone is as strong as you.”

“They’d better learn to be, or they’ll be dead in a few weeks.”

“They’ll survive. The Mugenese are gone.”

“Oh, you think it just ends like that?” Venka gave a brittle laugh. “You think it’s all over? Once they’re gone?”

“I didn’t mean—”

“They’re never gone. Do you understand? They still come for you in your sleep. Only this time they’re dream-wraiths, not real, and there’s no escape from them because they’re living in your own mind.”

“Venka, I’m sorry, I didn’t—”

Venka continued like she hadn’t heard. “Do you know that after Golyn Niis, the other two survivors from that pleasure house drank lye? Do you want to guess how many of these girls are going to hang themselves? They have no space to be weak, Rin. They don’t have time to be in shock. That can’t be an option. That’s how they die.”

“I understand that,” Rin said. “But you can’t take your shit out on them. You’re here to protect. You’re a soldier. Act like it.”

Venka’s eyes widened. For a moment Rin thought Venka might slap her, too. But the moment passed, and Venka’s shoulders slumped, like all the fight had drained out of her at once.

“Fine. Put them under someone else’s charge, then. I’m finished here.” She pointed to the whorehouses. “And burn that place to the ground.”

“We can’t,” Rin said. “They’re some of the only walled structures still standing. Until we can rebuild some shelters—”

“Burn it,” Venka snarled. “Or I’ll get some oil and do it myself. Now, I’m not very good at arson. So you can set a controlled fire, or deal with an inferno. You pick.”

A scout’s arrival saved Rin the burden of a response.

“We found it,” he reported. “Looks like there was only one.”

Rin’s stomach twisted. Not this. Not now. She wasn’t ready; after the whorehouses, she just wanted to shrink into a ball somewhere and hide. “Where was it?”

“About half a mile south of the city border. It’s muddy out there; you’ll want to lace on some thicker boots. Lieutenant Chen told me to tell you he’s already on the way. Shall I take you?”

Rin hesitated. “Venka …”

“Count me out. I don’t want to see that.” Venka turned on her heel and called over her shoulder as she stalked off, “I want the whorehouses in ashes by dawn, or I’ll assume it’s my job.”

Rin wanted to chase after her. She wanted to pull Venka back by the wrist, hug her tight, and hold her close until they were able to sob, until their sobs subsided. But Venka would interpret that as pity, and Venka detested pity more than anything. She read pity as an insult—as confirmation that, after all this time, everyone still thought her fragile and broken, on the verge of falling apart. Rin couldn’t do that to her.

She’d burn the whorehouses, she decided. The survivors could survive a few nights in the open air. She had fire enough to keep them warm.