Полная версия

An Atlas of Extinct Countries

Dedication

For Elise

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 Introduction

7 Chancers & Crackpots

8 The Kingdom of Sarawak

9 The Kingdom of Bavaria

10 The Islands of Refreshment

11 The Kingdom of Corsica

12 The State of Muskogee

13 The Republic of Sonora

14 The Kingdom of Araucanía & Patagonia

15 The Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace

16 Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

17 The Principality of Trinidad

18 The Fiume Endeavour

19 The Kingdom of Sedang

20 Mistakes & Micronations

21 The Republic of Cospaia

22 New Caledonia

23 The Principality of Elba

24 Franceville

25 The Republic of Vemerana

26 The Soviet Republic of Soldiers & Fortress-Builders of Naissaar

27 Neutral Moresnet

28 The Republic of Perloja

29 The Quilombo of Palmares

30 The Free State of Bottleneck

31 The Tangier International Zone

32 Ottawa Civic Hospital Maternity Ward

33 Lies & Lost Kingdoms

34 The Republic of Goust

35 Poyais

36 The Great Republic of Rough & Ready

37 Libertalia

38 The Kingdom of Sikkim

39 The Kingdom of Axum

40 Dahomey

41 The Most Serene Republic of Venice

42 The Golden Kingdom of Silla

43 Khwarezmia

44 Puppets & Political Footballs

45 The Republic of Formosa

46 The Republic of West Florida

47 Manchukuo

48 The Riograndense Republic

49 Maryland in Africa

50 The Republic of Texas

51 The Congo Free State

52 Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine)

53 The People’s Republic of Tannu Tuva

54 The Republic of Salò

55 The German Democratic Republic

56 Bophuthatswana

57 The Republic of Crimea

58 Yugoslavia

59 Flags

60 Anthems

61 Select Bibliography

62 Acknowledgements

63 Also by Gideon Defoe

64 About the Author

65 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivv1234568910111214151617182021222425262830313234363738404243444647485052535456585960626465666870717273747677788082838486888990929394969899100102103104106107108110112113114116118119120122123124126127128130132133135136138139140142143144146148149150152154155156158160161162164166167168170172173174176178179180182184185186188190191192195196198199200202204205206208209210212214215216218220221222224226227228230232233234236238239240242243244246247248250252253254256258259260262264265266268270271272275276277278279280281283284285286287288289ii

Introduction

Generous to a Fault, they Died Doing What they Loved, Exporting Tin

Countries die. Sometimes it’s murder. Sometimes it’s an accident. Sometimes it’s because they were too ludicrous to exist in the first place. Every so often they explode violently. A few slip away unnoticed. Often the cause of death is either ‘got too greedy’ or ‘Napoleon turned up’. Now and then they just hold a referendum and vote themselves out of existence.

These are the obituaries of the nations that fell off the map. The polite way of writing an obituary is: dwell on the good bits, gloss over the embarrassing stuff. A book about dead nations can’t really do that, because it’s impossible to skip the embarrassing stuff – there’s far too much of it. The life stories of the sadly deceased involve a catalogue of chancers, racists, racist chancers, con men, madmen, people trying to get out of paying taxes, mistakes, lies, stupid schemes and a lot of things that you’d file under the umbrella term of ‘general idiocy’. Because of this – and because treating nation states with too much respect is maybe the entire problem with pretty much everything – these accounts do not respectfully add to all the earnest flag-saluting in the world, however nice some of the flags are.

If you’re a contestant on Pointless and want a book that sticks to a firm definition of what a country is, you are owed an apology.* You could write a very dry essay on all the failed attempts to define what counts as a ‘country’, and if very dry essays are your thing then there are already a fair few out there. None of them get particularly close to an answer. There is something in biology called ‘the species problem’. The problem being: after years of arguing about it, nobody can agree what criteria actually define a ‘species’. Countries are no different. We switch definitions depending on whether we’re at the United Nations, playing football, singing in Eurovision or buying cheese. It’s a mess.

Having said that, here are some arbitrary rules: I’ve avoided delving too far into the past, because talking about ancient places as ‘nation states’ is sort of meaningless when the idea itself didn’t exist until the last few hundred years. I’ve ignored empires and colonies. I’ve left out places where the name has changed but the shape on the map has stayed the same. I’ve then immediately forgotten those rules by including Silla, Axum, New Caledonia and the Congo Free State. Please address angry letters about that to Richard Osman or the UN Secretary-General. Or just pretend it’s ‘in the tradition of Herodotus’, which is a fancy way of saying that the story is more important than getting bogged down in endless caveats (caveat: caveats are good, and you should be rightfully suspicious of anything that tries to sum up the history of a place in 500 words).

If ex-nations seem unimportant in the big scheme of things then it’s worth remembering that, like a Marvel superhero cash cow, countries don’t always stay dead. Humans live in a constant state of changing their minds about the type and number of other humans they want to be categorised with, so we oscillate from tiny blobs to huge empires and back again, and there’s no reason to assume that process will ever stop. Within a decade, some of these geographical zombies might claw their way out of the graveyard and back into the atlas.

Please send hard currency in lieu of flowers. ALL HAIL NEUTRAL MORESNET.

A note on the locations: These maps use the what3words geocoding system. Instead of latitude and longitude, a set of three randomly assigned words can be used to uniquely identify the location of anything in the world, down to a resolution of three metres squared. One of the benefits of this is that it’s much easier to remember three words than a string of numbers.

Visit what3words.com for more information.

* Another apology: a lot of these places are the stories of Posh White Guys, which is an unavoidable product of a time when only Posh White Guys felt entitled enough to go and set up countries.

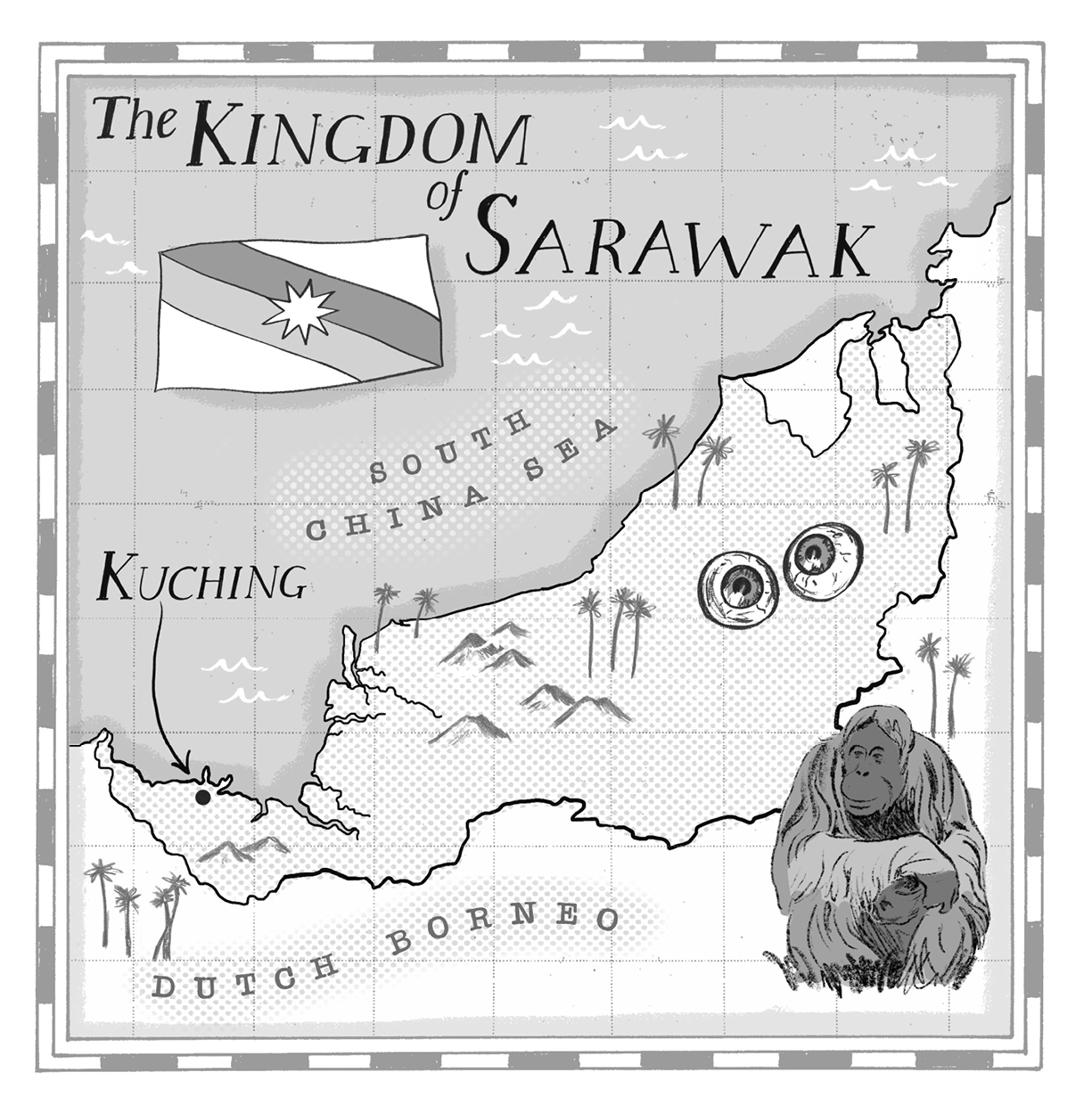

The Kingdom of Sarawak

1841–1946

Population: between 8,000 (1841) and 600,000 (1946)

Capital: Kuching

Languages: English, Iban, Melanau, Bidayuh, Sarawak Malay, Chinese

Currency: Sarawak dollar

Cause of death: sold to the British

Today: part of Malaysia

///compound.melons.orchestra

While still a school kid, James Brooke declared his intention to run away to sea. He got as far as his gran’s garden in Reigate. This combination of a lust for adventure, being slightly overdramatic and messing stuff up would be the main themes running through the rest of his life.

No less determined to see the world by the time he was a teen, he joined the army, where his glorious military career ended as soon as it began. Charging into battle he was immediately shot, possibly in the lung, possibly somewhere significantly worse.*

After a painful recuperation, Brooke tried again. He already knew that his fabulously wealthy father was a soft touch, because when his brother had asked for an elephant, Brooke Senior obligingly had one shipped over at huge expense. James didn’t want an elephant. He wanted a boat. Daddy obliged.

With his new toy, Brooke sailed for Borneo: the nineteenth-century poster child for savage, lush exoticism. The indigenous population, the Dayak, was divided into complicated rival factions, constantly skirmishing with each other, though mostly in the form of violent dance-offs. Brooke successfully played the competing groups against each other – taking the side of the ‘land dayaks’, rather than the piratical ‘sea dayaks’ (a terminology that he invented). Bringing a measure of order to the local chaos, he was awarded a chunk of territory by a grateful Sultan of Brunei, who had wrongly assumed that Brooke, very much a private citizen chancer, somehow represented the British Empire. He was also given a pet orangutan called Betsy.

Aged just 38, he had his own kingdom. ‘I am really becoming a great man, dearest mother,’ Brooke wrote in a letter home, displaying all the modest self-effacement that rich English Victorian white dudes are generally famous for. But in an era of greedy Brits abroad, Brooke only registers as about a five-out-of-ten on the Imperialistic Git scale. He seems to have genuinely wanted the best for ‘his people’, albeit in the patronising paternalistic way of the time. He set up a court of justice to bring law to his new domain, and famously sentenced a man-eating crocodile to death (because, though he respected and sympathised with the animal, he didn’t want the other crocodiles to get the wrong idea about what was ‘acceptable behaviour’). The local Dayak population were keen headhunters,† an activity Brooke tried semi-successfully to discourage – and however much of a cultural relativist you are, that’s probably not the worst thing in the world.

At first, Brooke became a national hero back in Britain. But in a rare bit of imperial navel-gazing, some wondered if swanning off and starting your own kingdom was perhaps a Bit Much. Political enemies accused him of massacring innocents. Brooke claimed they were pirates. There was an enquiry, which in the usual style of government enquiries quickly got bogged down in weird little details, like trying to define what a pirate was. Did pirates have to have sails? What if they just had paddles? Predictably, nothing came of it.

Sarawak slid into debt, and Brooke’s local crush‡ was killed during a Chinese insurrection. He became increasingly depressed and hoped the United Kingdom would buy the country off him, but they weren’t keen. So the rule of the ‘White Rajahs’ bumbled on, with the title passing to Brooke’s nephew, Charles, who did a decent job of getting the place back on its feet, and whose most distinguishing feature was a glass eye (purchased at a taxidermist’s and intended for an albatross – though one rumour suggested that he had a range of different fake eyes from different creatures, to wear according to his mood). Charles in turn was succeeded by his son, Vyner. Vyner had a difficult time of it. He had been forbidden from eating jam as a child because his dad deemed it ‘effeminate’ and grew up so socially anxious that he would hide from guests in a cupboard. Hiding in a cupboard wasn’t going to be enough to avoid World War II and the Japanese invasion that came with it. Vyner fled to Australia. Once the war was over he briefly regained his kingdom, only to find it bombed to bits. With nothing left in the Sarawak coffers to rebuild, Vyner faced up to the inevitable. He finally persuaded the British to take it off his hands in exchange for a big lump of cash and all the jam he could eat.

* Probably lies: it seems likely that, in an era when homosexuality was punishable by death, the rumour that Brooke had been shot through the penis was just a neat way to explain away his perpetual bachelordom.

† The Dayak viewed headhunting as means of consecrating important events. It was considered extreme bad luck not to give a human skull to your wife at the birth of your child.

‡ James Brooke seems to have fallen for the local rajah’s brother, Badrudeen, and wrote a lot of torturously evasive diary entries about him.

The Kingdom of Bavaria

1805–1918

Population: circa 6.5 million (1910)

Capital: Munich

Languages: Bavarian, Upper German

Currency: Bavarian gulden, German goldmark

Cause of death: bad genes and Bismarck

Today: part of Germany

///subtexts.photos.dietary

Every morning, Ludwig II, the fourth King of Bavaria, would have his barber tease out his hair into a weird bouffant that made his head look massive. He claimed that without his daily coiffure he could not enjoy his food. If a servant happened to accidentally stare at him and his big hair for too long, Ludwig would empty a washbasin over them. That’s what a few hundred years of royal inbreeding gets you.

Bavaria existed as part of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries, but it was only after Napoleon steamrollered Austria in 1805 that it became a kingdom. The relatively normal King Maximilian helped defeat the French and managed to expand the country’s borders as a reward for his troubles. Maximilian was followed by his son Ludwig. Ludwig I was both a patron of the arts and a notorious lothario* (he commissioned a series of portraits of ‘famous beauties of the day’) but the old lech (61) met his match in Lola Montez (28). An Irish dancer posing as an exotic Andalusian, Lola had already barrelled through Europe, leaving chaos in her wake. She’d caused a riot in Warsaw, shocked high society in Paris, and had a scrape with the cops in Berlin. When she arrived in Munich she shacked up with Ludwig and persuaded him to liberalise the place, which didn’t win him many friends among the ultra-conservative Catholic aristocracy. At the same time, revolutionary fervour swept through Europe in 1848, and Ludwig, besieged from all sides, decided to abdicate, correctly guessing that a nice retirement pottering around his garden would be a lot more fun than being a head of state.†

His son, Maximilian II, valiantly tried to keep the kingdom from getting hoovered up by Otto von Bismarck, who was now embarked upon his grand project to unify Germany under a dominant Prussia. But the new king inconveniently died young in 1864, which brought on the reign of Ludwig II and his big hair. It’s unfair to say that Ludwig didn’t care about ruling Bavaria – he worked quite hard at the job – but it certainly wasn’t where his heart lay. That was with opera. More specifically, the operas of genius/all-round horrible anti-Semite Richard Wagner. Ludwig was Wagner’s number-one fan. He built his idol a world-famous opera house. He wrote stacks of letters to the composer, none of which contain a single joke. He almost bankrupted himself constructing over-the-top fairy-tale castles (sketched out by Wagner’s stage designer). Contemporary wags started referring to Wagner as ‘Lola Two’. Faced with the task of having to juggle loyalties to wily Bismarck and the Austrians, all Ludwig wanted to do was run away with his pal to Switzerland. He backed the wrong side in the Austro-Prussian War, and by 1870 had been forced, distracted by toothache, to join victorious Prussia’s North German Confederation.‡ He at least managed to maintain a degree of independence for his kingdom – they kept their own army, railways and postal service, and he could go on building his fantastically camp castles.

The strain of trying to navigate Bavaria’s path through the tangled politics of the times started to show. The revisionist take is that Ludwig wasn’t mad in any medically recognised way, but that his doctors plotted with political enemies to label him as such. It’s impossible to say, though nobody disputes that he became troublingly erratic and, if not mad, then certainly a bit of a dick. He took to ordering people to be executed for sneezing (orders which were quietly ignored). At one point he tried to hire bandits in a bizarre scheme to capture the Prussian crown prince and have him ‘chained up in a cave’. He’d organise expensive performances of plays for which he was the only audience member.§

Concerned ministers or political rivals (delete at your discretion) decided enough was enough and took him away to be ‘cured’. Locked in the grounds of Berg Castle, Ludwig went for an evening walk with his physician. The bodies of both men were found a little later floating in the nearby lake. Whether misadventure or suicide or good old-fashioned murder, the kingdom wouldn’t recover. The title officially passed to Ludwig’s brother Otto at first, but he was definitely insane, and so his uncle Luitpold ruled as regent. For the next few years Bavaria passively slipped further and further into the clutches of the German Empire, almost without anyone noticing. It was an oddly underwhelming end for such a headline-grabbing dynasty.

* Ludwig I’s wedding was the first Oktoberfest. Bavaria would later make the adoption of its beer purity law a condition of joining the German Empire.

† After her stint in Bavaria, Lola headed to California where appreciative miners would supposedly throw gold nuggets at her.

‡ Bismarck did not endear himself to the Bavarians when he described them as ‘half-way between an Austrian and a human being’.

§ Ludwig II tried to go on holiday with an actor friend, but his efforts to travel incognito went awry when a boat he hired in Lucerne turned up decked out in Bavarian flags and the captain greeted him as ‘your majesty’.

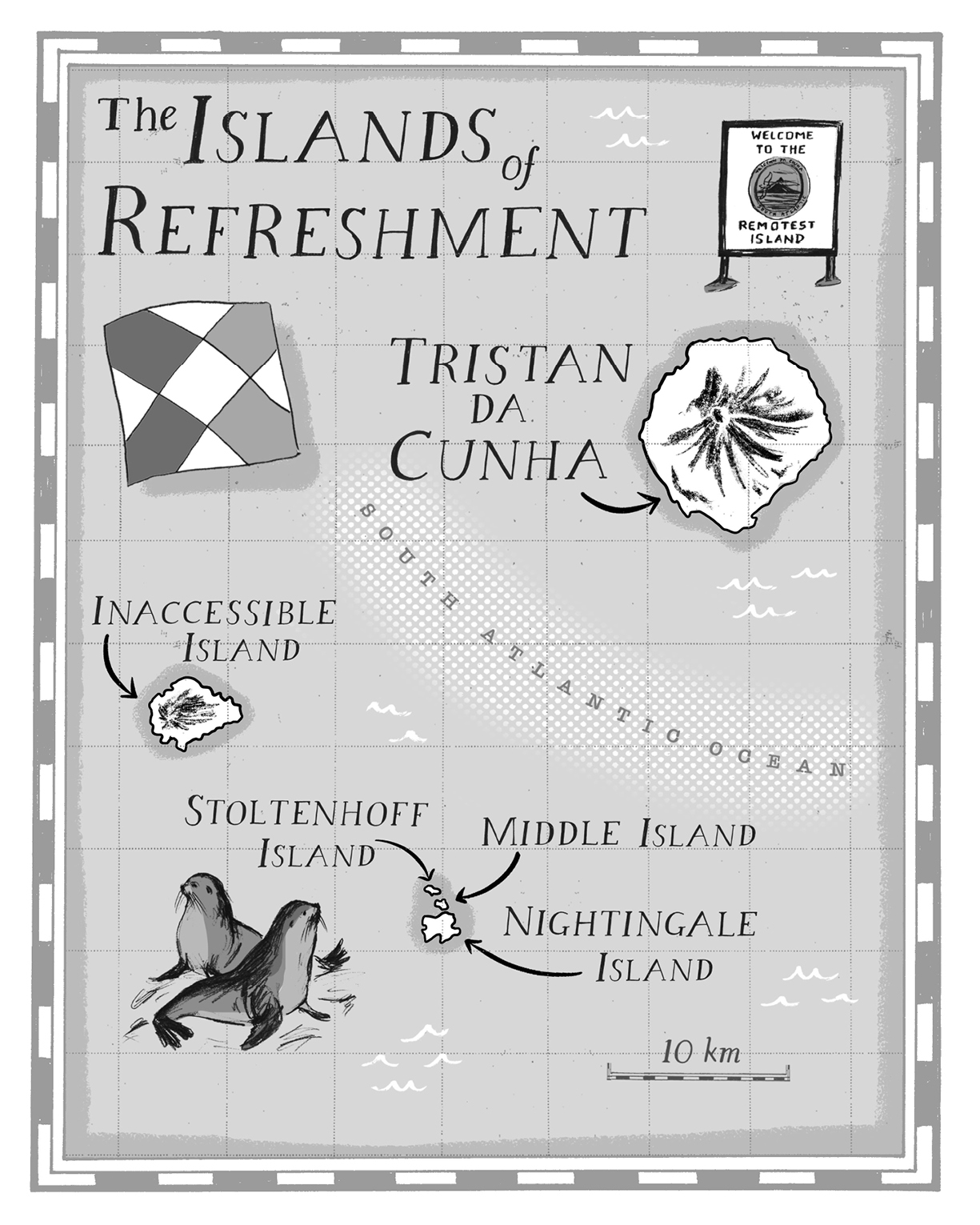

The Islands of Refreshment

1811–16

Population: 4

Cause of death: a boating accident

Today: a British Overseas Territory

///untiring.cranes.skimmed

Today there is a sign on Tristan da Cunha welcoming visitors to ‘the Remotest Island’. 1,500 miles from anywhere, this isn’t tourist-board hyperbole. The Portuguese explorer Tristão da Cunha spotted the tiny volcanic speck in 1506, but decided it looked too unappealing to stop off at. It wasn’t until 1811 that the first would-be permanent settler showed up, a young adventurer from Salem, Massachusetts, named Jonathan Lambert.*

He’d hitched a lift on a whaling ship, along with a dog and three companions. One of these, Thomas Currie, had been promised 12 Spanish dollars a month to help set up a new country. They rowed ashore and Lambert boldly announced the land as his own, ‘solely for myself and my heirs for ever’. He instantly embarked on a rebranding exercise, collectively rechristening da Cunha and its two equally windswept neighbours (‘Nightingale’ and ‘Inaccessible’) with a more approachable-sounding name – the Islands of Refreshment. This welcoming kingdom had the stated aim of providing refreshment to passing travellers – ‘all vessels, of whatever description, and belonging to whatever nation, will visit me for that purpose’. Lambert had, in effect, set up a glorified motorway service station, but in the stupidest place possible: an obscure part of the Atlantic where the only passing ships, as far from civilisation as they could be, were inclined to nick stuff rather than pay for it.†

Just like a real motorway services, things were bleak. The new inhabitants butchered an enormous number of seals, hoping to make enough oil from the blubber to sell to passing mariners to pay for a nicer boat. They ate a lot of turnips, their only substitute for bread. Life proved difficult. Then, in 1812, one year into the project, Lambert and two others disappeared: presumed drowned in a boating accident while out fishing. Thomas Currie – seething about never having been paid by his vanished boss – was left to fend for himself.

It was a grumpy Currie who recounted the whole sorry escapade to the British when they turned up four years later. They’d come to claim the island as a naval base, worried it might otherwise be used as a stopping-off point from which to mount a rescue of Napoleon, newly exiled on St Helena. It seems like precautionary overkill, because St Helena is still 1,343 miles away, but they’d learned their lesson from the whole Elba fiasco.

Swallowed by the British Empire, the independent Islands of Refreshment were no more, but this new occupation finally led to a slightly more successful community getting established there. Nowadays they even have a British postcode.‡ Though they also have several cases of progressive blindness caused by retinitis pigmentosa, because Tristan da Cunha has become an unfortunate case study in why tiny gene pools are Not A Great Thing.

* Probably lies: Lambert thought he was the first person to ever stay on the island, but the presence of pigs suggests other people, possibly Dutch traders, must have stopped off first, at least briefly.

† Today, it is still a six-day boat journey from the nearest mainland, South Africa.

‡ Evacuated to Hampshire in 1961 after a volcanic eruption, virtually the entire population voted to return to the island, so it can’t be as bad as Currie made out.

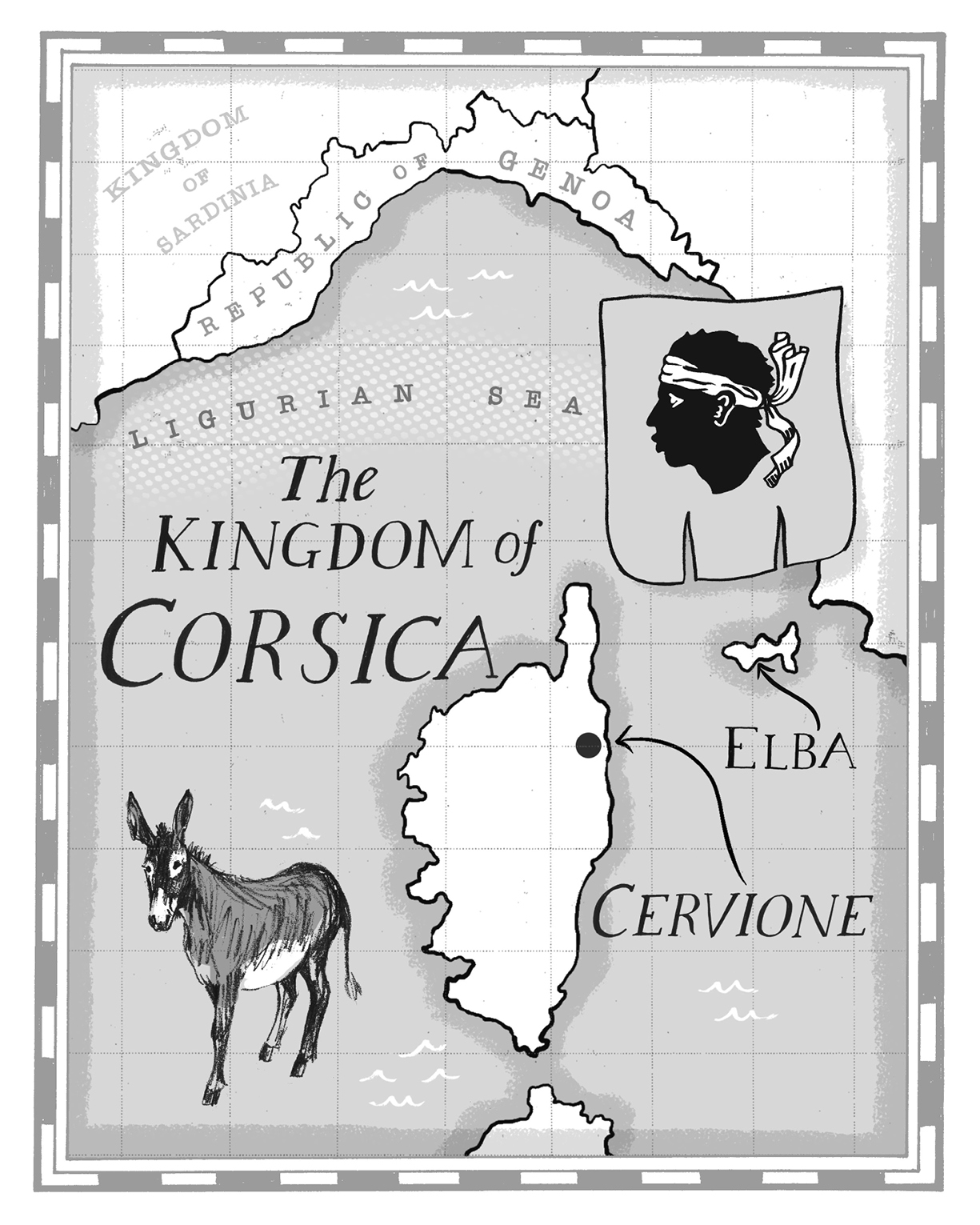

The Kingdom of Corsica

March–November 1736

Capital: Cervione

Languages: Italian, Corsican, French, German

Currency: soldi

Cause of death: in-fighting and bad debts

Today: part of France

///auctioning.politicians.fatten

Theodore Stephan Freiherr von Neuhoff – of ‘fine form and a handsome face’ – left a trail of debts, inspired an opera and a couple of novels, got punched by jealous husbands, and basically did all the eighteenth-century Errol Flynn stuff you could hope for.

Born into a semi-noble family in Cologne, he joined the army at 17, where he started a lifelong habit of racking up huge gambling losses.* Then he did a runner across Europe, marrying one of the Queen of Spain’s maids en route. Whose jewellery he then stole, before heading back to Paris where he used the swag to invest in one of the first financial bubbles.†

Aged 26, bankrupt and living in south London, von Neuhoff hid in bed to avoid his creditors, read books about highwaymen and got heavily into alchemy. He quit England and headed back to the continent, where he had an affair with a nun. The only thing more illegal than having an affair with a nun was working as a ‘magicotherapist’, so he did that too, telling people he could predict lottery numbers, exorcise demons and make love potions.‡ While plying this slippery trade in Genoa, he encountered some Corsican rebels. The rebels were after self-determination, free from the yoke of the Genoese. Everyone hated Genoa by this point in history, and the Corsicans had a legitimate grievance – they were regarded as ‘barbarians’ by their rulers, and forbidden from hunting or fishing.§ Partly attracted by the romance of helping the plucky underdog, mostly attracted to the opportunity of smuggling coral, Theodore agreed to help them, on the proviso that, should this all work out, he be declared king. He borrowed money – borrowing money being his main skill – and purchased arms for the cause. He sought alliances in Turkey and Morocco but, sympathetic as they were, nobody wanted to get involved. So, he returned to Corsica, decked out in his new king outfit (fur-trimmed robe, plumed tricorn, gilded cane) and – either by luck or unexpected military skill – drove the Genoese back to a couple of fortified enclaves.