Полная версия

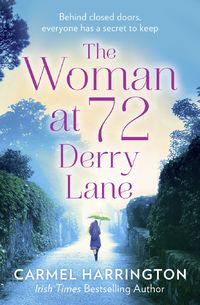

The Woman at 72 Derry Lane

‘I wasn’t asking him, it was you I invited. And he doesn’t need to know what you do when he’s at work, does he?’ Rea smiled.

‘No, I don’t suppose he does.’ Stella looked at Rea, still feeling the soft warmth of the woman’s hands on hers. She felt an urge to throw herself into the older woman’s arms. But before she got the chance to make a fool of herself by doing that, Louis kicked a stone up the drive.

‘Ma said you wanted me.’

Chapter 9

SKYE

Rathmines, Dublin, 2000

‘I hate you both. It’s not fair!’

My attitude to our dream holiday fund going on replacing Dad’s car was not my finest hour.

I’m ashamed to say that I was reacting with true teenage belligerence and I did nothing to ease the guilt of my parents, who hated to disappoint us.

It wasn’t their fault our car had decided to give up on life and we had to cancel the holiday, and I knew it, but even so, I just couldn’t stop myself. I wanted to make them feel pain like I was feeling. I was crippled with disappointment. And if I was honest, I felt mortification knowing that all my boasts in school about the holiday would now be jeered at. When would I learn to keep my big mouth shut?

My selfish wish was granted when they both winced in pain at my words. But the thing was, it didn’t help in the slightest. I still felt crap, and knowing that they did too didn’t change that. Now, not only was I miserable but guilt flooded me. Even so, I didn’t do anything to make them feel better, though. I stormed out, slamming the door behind me for good measure.

And so ended our first Dream Holiday Fund. We used the savings to buy a new family car, or at least a new car to us. It took me a while to stop doing a big dramatic sigh every time I squeezed my legs into the back seat. I hated that car and now I only have to see a green Ford focus to bring me down.

‘We went for a 1.2L engine,’ Dad told us. ‘That way the tax is half what it used to be for the old car. And the savings from that will go straight into our new holiday fund, I promise.’

It was hard staying annoyed when you heard statements like that. Dad looked so earnest and Eli gave me a look that spoke volumes, along the lines of ‘Cop on Skye, give the folks a break.’

‘We’ll be no length filling that jar again. As I always say, watch the pennies …’ Mam said.

And so, I chimed in, along with Eli and Dad, saying, ‘and the pounds will take care of themselves.’

‘We’ll get to paradise yet, love, I promise,’ Mam said, giving my arm a squeeze, and I believed her. This was just a little hiccup.

We fell into our familiar rhythm of saving. Dad got a promotion and Mam started to work in the local Supervalu. Eli and I continued doing our part-time jobs and we were back to being a family of thriftiness.

It was around this time that Mam decided she wanted to write a book. She went to see one of her favourite authors, Maeve Binchy, give a talk in our local library and came home all fired up.

Dad said, ‘Sure, everyone has at least one book inside of them.’

Things got a bit weird after that at home. Mam took to saying things like ‘plot twist!’ whenever something went wrong. She thought she was hilarious and, in fairness, we usually did laugh in response. Dad bought her a journal and she was never without it. Eli and I couldn’t open our mouths without her scribbling something into it.

‘That’s gold, pure gold,’ she’d mutter, scribbling away, her glasses perched on the end of her nose.

‘What did we say?’ Eli would ask.

‘That book better not be about me,’ I declared and she’d just look enigmatic. ‘You’ll just have to wait and see.’

One day, when she wasn’t looking, I stole a glance inside her journal. I couldn’t take any chances. I mean, I didn’t really think she had a cat’s hell in chance of ever getting published, but imagine if she did and the main character was called Skye and she wasn’t very nice.

I simply had to see what she was writing, why she was being so secretive? And if there was one thing about me that I didn’t like, well, she’d better watch out, because … hang on! What on earth was all this? I couldn’t see any semblance of a novel in her journal. It was full of shopping lists, the latest entry being Buy soap for John! And reminders to do things like, ring Paula. And the cheek of Mam, one even said, Skye’s hair is looking scraggy, book hair appointment.

As I said to Dad and Eli later that night, ‘That book that you kept saying was inside of Mam, well it’s sure doing a bad job of showing itself!’

‘Say nothing,’ Dad replied, when we’d all calmed down from laughing. ‘Your mother is enjoying exploring her creative side. You never know, maybe she’ll surprise us all one day.’

‘Plot twist, Mam gets a book deal!’ Eli said and we were off again. I swear I thought Dad was going to have a heart attack, he was laughing so much.

Another rainy summer in Ireland passed by and then, a quite warm Christmas, as it happens. And fourteen months after our second attempt at the Dream Holiday Fund began, Dad declared we had saved enough. We attempted to do another mad dance around the table, but it didn’t feel the same as the last time. But we did debate long and hard as to where Paradise would be for the Madden’s this time.

I don’t know why, but all of a sudden, Florida no longer held a lure for us. You see, Mam’s manager in Supervalu was forever boasting about all the cruising she and her husband had done. And over dinner most evenings, Mam would recount the stories to us and we would all hang onto her every word about midnight chocolate buffets and swimming pools with outdoor cinemas. It sounded lush.

‘So are we saying now that we should go for a cruise?’ Mam asked, her face alight with excitement. I liked seeing her look so happy.

‘You had me at the chocolate buffet,’ Dad said and Eli and I nodded in agreement. A cruise sounded exotic and grown up. And at almost sixteen, I wanted to be both of those. Plus, nobody in school had ever been on a cruise. Take that, Faye Larkin!

The day I finished my last junior cert exam, as we all gorged on big bowls of ice-cream sundaes that Mam made in celebration, she said, ‘I wonder how many of these boys we could put away in that free buffet they have?’

‘I’d eat ten of these without even thinking,’ Eli retorted. At eighteen, he was lean, tall and had an appetite that never was satisfied. Yep, he wasn’t lying. With ease he’d do that.

‘Well, let’s put that boast to the test. Get me the laptop there, Skye, and we’ll book ourselves a cruise.’

‘For real?’ I said, completely floored.

‘For real,’ Mam replied gently.

Eli and I didn’t celebrate until the moment that Dad actually paid the deposit. When he hit send on the words, Confirm Payment, we both held our breath. And then, all of sudden, it felt absolute. Dad started to sing ‘We Are Sailing’ by Rod Stewart and even though Eli and I didn’t know the words, we all joined in as best we could. I prefer to make my own words up anyhow. Mam started to wear scarves jauntily tied around her neck, or over her head, with big dark sunglasses. She told us she was perfecting her ‘cruise lounge wear’ and we took delight in jeering at her. But in my bedroom, when nobody was around, I tried on every single outfit I owned, planning my own cruise wardrobe.

I’d never had a boyfriend and I daydreamed that maybe my first one would be someone foreign and exotic. Maybe the son of a rich tycoon. With his own helicopter or private jet. That would be so cool. He’d be called Brad and he’d fall in love with me instantly. Yes, someone like Brad would certainly cruise a lot. Faye Larkin would die, she’d be so jealous.

Dad came home the next day from work with a bag full of sailors’ caps he’d bought in the euro store. When we all put ours on Mam giggled so much that she told us a little bit of pee came out. Sometimes my parents had no filter. She couldn’t be saying stuff like that on a cruise. What if Brad heard?

I got out my pencils again and made a countdown chart. We had forty-eight days until our departure date. I stuck the chart under a pineapple magnet on our fridge door.

Now I can’t even look at a pineapple without wanting to throw it hard against the wall, smashing it into smithereens.

Because before we got any wear out of the sailor caps our second curve ball was propelled at us, at great speed. Another clue from the universe telling us to stay home. Paradise is not meant for the Maddens, it screamed. Stop dreaming of foreign shores. Go on down to Sneem and do the Ring of Kerry for the twentieth time. It’s safer. But the universe’s warnings fell on deaf ears.

It was forty-six days until departure day when a phone call changed everything.

Chapter 10

SKYE

Eli burst in from the hall, whispering to me and Dad that something was wrong with Mam. We walked out and she was ashen, silent, nodding over and over again, as she listened to the call.

‘What is it, love?’ Dad asked and she ignored us, or maybe just didn’t hear him, I don’t know. Minutes felt like hours as we waited for her to hang up and tell us what was wrong. Whatever it was, it had trouble written all over it. She walked slowly into the kitchen, shaking and tearful as she sank into one of the chairs.

‘Give your mother some space. Put the kettle on, Skye,’ Dad said and Mam reached her hands out to clasp his.

‘It’s Aunty Paula. She’s got cancer. Breast cancer. They have to do a full mastectomy next week.’

Dad sank into a chair beside Mam and he kept shaking his head, as if that would make the words go away and not be true. It was the first time that anyone in our family had ever been sick and we were all thrown by it. I felt panic and terror battle their way into my head. And looking at my family, we were all feeling the same.

The next week went by in a blur. Mam went down to Sneem and daily phone calls came with more damning updates. Aunty Paula’s cancer had spread to her lymph nodes. It was aggressive. More surgery. Mastectomies. Long talks with doctors were had, discussing treatment options. Paula would need chemotherapy and then radiotherapy.

‘A long hard road ahead of her,’ Mam told us.

When Mam came home two weeks later, her shoulders sagging, she looked older. Lines seemed to have sprung up on her face and there was a sprinkling of grey in her hair that hadn’t been there two weeks ago. The whispering in corners began again. When they called Eli and me into the good sitting room we stood close together, shoulder to shoulder, bracing ourselves for the bad news.

I whispered to Eli, ‘I think she’s dead.’ And he nodded in response and reached out to hold my hand.

I can remember looking down at our fingers clasped together and thinking that it was years since we’d done that. We used to play outside as kids, hand in hand, skipping around our garden as we came up with new adventures. I’d forgotten how much comfort I took from that hand. I felt the welts on his fingers, earned from his many woodwork projects. And when he squeezed my hand tight, I wished we were kids again and could skip our way to another land. Lose ourselves in our imaginations, far away from the damning imminent news.

But we were wrong. Thank goodness we were wrong, because Aunty Paula was kind and we loved her dearly.

‘Things are tough for Paula right now,’ Mam said tearfully. ‘She has a big mortgage and money is tight …’ she stopped and looked to Dad for help. But he was silent too and just looked at us, twisting his hands.

Eli got it before me, as he always did. ‘We are going to give our holiday money to Aunty Paula, aren’t we?’

They nodded silently.

Paradise lost once more.

Like the last time, my immediate reaction wasn’t very nice. I wish I was the kind of person who jumped right in on occasions like these and said with grace, ‘it doesn’t matter.’ But all I could think about in that moment was the big cinema screen that overlooked the outdoor swimming pool on the mahoosive cruise liner and the first kiss that Brad would steal under the stars. All I could feel was bitter disappointment.

I remained silent, selfish as I was, and made my parents feel worse than they already did.

‘We’ve only paid a deposit, so we’d just lose that. I don’t think in any conscience I could head off on a cruise, spend thousands, knowing that …’ Mam started to cry.

Dad looked at Eli and me, imploring us with his eyes to be generous and kind and not give Mam a hard time. ‘That money from the cruise would pay her mortgage for six months. Give her time to catch her breath after the surgery. She’s chemo to face, not to mention the radiotherapy.’

Eli squeezed my hand again and I sneaked a glance at him, trying to work out where he was with the news.

‘It has to be a decision that we all agree on. Everyone in this family has contributed to that saving fund. And if one of you says no, we’ll leave it at that.’

I felt elated for a moment. I can say no. And who could blame me. I mean, we gave up our money the last time for Dad’s car. Aunty Paula wouldn’t want us to miss our holiday. She’s lovely.

Lovely. Aunty Paula is lovely.

Memories of all those times she’d come to stay. Arms loaded down with all the gifts she had spoiled us with over the years. Arms open wide for all the warm hugs and cuddles she doled out with that same generosity. Only last month she’d sent down a new top for me that she’d noticed in a shop near her. Her note said, ‘It’s just your colour and will look gorgeous on you.’ And it did too. I wore it out the other night to the cinema with the girls and they all raved about it.

Oh Aunty Paula. Of course we had to give her the money.

I felt eyes upon me and realised that my family were waiting for me to speak. ‘It’s just another plot twist,’ I said and walked over to hug Mam, who was crying again. ‘We’ll start saving and, sure, what do they say? Third time lucky. Aunty Paula is more important.’

Everyone nodded in agreement at my words. But we didn’t put the jar back on the dresser for a long time. We lost our saving mojo, I suppose, and although none of us said it, we kind of thought, what’s the point?

Mam’s potato parer was relegated to the back of the cutlery drawer and Saturdays became takeaway nights again. Actually, we ate a lot of takeaways that year, because Mam was away from home a lot and Dad was at work. Days became weeks and then months as chemo treatments rolled by. Then came the radiotherapy. It all took its toll on Aunty Paula and on all of us. Mam in particular. It was a horrible year, all in all. I don’t think we smiled much, at least not that often.

Then one evening Dad came home with a scratch card for Mam ‘Might give her a lift,’ he whispered to Eli and I. She wasn’t herself, worn down with tiredness and worry about her baby sister.

The gods were looking down kindly, because Mam suddenly shouted, ‘I won €50!’

We all whooped in pleasure for her.

‘You should book yourself a facial, you love having a pamper day,’ Dad told her.

‘Or get yourself that nice top you mentioned you saw in Carrig Donn,’ I added.

‘Here, Mam, you should do both,’ Eli slid something across the table towards her. ‘Here’s another twenty to add to the fifty. I sold one of my garden benches today.’

All of Eli’s practice was beginning to pay off and his joinery was widely acclaimed as exceptional. Mam looked at us all and smiled through watery eyes. Then it was like Groundhog Day because she stood up and walked over to the dresser and crouched down low, looking through the over-stuffed press.

‘Where is it? I know I left it here somewhere …’ she mumbled and then, ‘Ha! Got you!’

She looked at each of us. We couldn’t take our eyes off her and then she placed the holiday jar back in its rightful place on top of the dresser. She held up her lottery ticket and Eli’s twenty euro, saying, ‘Third time lucky, that’s what you said, Skye.’ She placed them into the slot and I felt excitement shiver down my spine.

This time we will get to paradise. I just know it.

Chapter 11

REA

Derry Lane, Dublin, 2014

‘You took your time,’ Rea grumbled, letting Louis in.

‘I told you I’d be back. Had to get something to eat first.’ He wrinkled his nose and laughed, ‘I see what you mean. There’s a powerful twang off that bin alright.’

The smirk on Louis’ face should have irritated Rea, but it didn’t. The little shit knew that she was at his mercy, but even so, his sheer audacity amused her. He had spunk, get up and go. He wasn’t afraid to hustle and at least he was honest about it. But despite the fact that Louis Flynn was her only contact with the big wide world outside, he was enjoying himself far too much for her liking. So she scowled at him, her mind ticking over ways to bring him back down a few notches.

‘That cheap aftershave of yours sure is nasty, gives a shocking twang alright.’ Rea tried hard to mimic the boy’s smirk and it must have worked because his face fell. Then he gathered himself together and said with an exaggerated wink, ‘I wouldn’t waste the good stuff coming in here to see an aul wan’ like you.’

She snorted in response to cover the laugh that was trying to escape and turned away so he couldn’t see her face.

He carried on channelling his inner Del Boy, ‘I’m a busy man. People to see, things to do. So let’s cut to the chase. I’ve given you my new terms, take it or leave it.’

‘A busy man, you say?’ She looked him up and down once more and sneered, ‘A busy boy, you mean! And what has you so overloaded?’

Rea took out two glasses from the press and poured Fanta orange into them both. Then she grabbed her treat jar and opened the lid, pushing it towards him. He dived in, rooting around till he found his favourite at the bottom – the Twix bars. Rea noted to herself that she’d better add them to her Tesco online shopping list, she’d nearly ran out.

He gulped back the fizz in seconds, then burped loudly, delighted with himself, winking at her. ‘Both.’

‘You’re a pig, Louis Flynn.’

‘Maybe, but I’m a pig who right now is the only one willing to empty your bins. So either you agree to twenty euros a week for that Class A service or I’m out of here.’

‘You only have to bring the bins a few hundred feet down the path, all in all, which takes you less than five minutes each time!’

‘You do it, then, if it’s so easy,’ he replied, sly as a fox. He had Rea over a barrel and he knew it.

‘What would your mother say, if she knew you were trying to quadruple our agreed rates?’

‘She wouldn’t care less. She’s too busy with her latest fella.’

‘A new fella? Sure, she’s only just set the last one packing!’ Rea threw her eyes up to the ceiling.

‘It’s some gobshite who delivers pizzas for Harry’s. They fell for each other over a Hawaiian deep crust.’

Rea had a bad feeling about this. ‘Don’t tell me he has an earring …’

‘Yeah, he does. Size of it, a big round hoopy yoke that girls usually wear. Why?’

‘I know, I’ve never seen anything so ridiculous in my life,’ Rea said. ‘He delivered a pizza here the other night and I told him to go … well, never mind, let’s just say I had words with him.’

‘You can’t leave it like that, Mrs B. What did you say to him?’ Louis was up off his seat, face lit up with excitement.

Buoyed by his enthusiasm, Rea said, ‘I may or may not have given him the finger.’

He roared laughing, delighted with the news. ‘I’d have loved to see that. We were his last call and apparently Mam and him were giving each other the eye last week in Tomangos. So she invites him in. He’s already strutting around like he owns the gaff, bleedin’ tool. And he ruffled my hair, calling me kiddo. Eejit!’

Rea pushed the tin towards Louis, saying, ‘Go on, have another one,’ and he smiled, reaching in for a second bar.

Rea leaned forward and said, ‘Tell you what, ten euro and that’s my final offer, that’s double what you get right now.’ Then she threw in a lie, just to rattle him. ‘That new family who moved into number 65, well, they’ve a lovely young girl, twelve years old and her mam was up here last week saying to me that she would love to help me out.’

He looked at Rea, doubt all over his young, spotty face.

‘Ten euro, take it or leave it. Or I’ll take my business elsewhere.’

‘Fifteen euro, take that or leave that, Rea Brady,’ he threw back at her. He’d some neck on him, she thought. She walked over to her phone and picked it up, making a big deal of scrolling through her contacts for a number.

‘Where is that number again? I’ll just give that lovely woman in number 65 a quick bell and ask her to send her daughter over. I’d say she’d jump at the chance to earn a tenner a week. Hell, the way her mam was talking, she’d probably do it for nothing. Sweet little thing. Well brought up. And, when I think of it, I’d be saving on all the treats too. Because she’d probably not eat me out of house and home every time she called.’

To illustrate the point, Rea picked up the tin and put the lid back on it.

‘Alright, ten euro it is,’ Louis said, the loss of treats tipping the negotiations in Rea’s favour. ‘Only because you gave yer man the finger. Respect for that, Mrs B.’

Rea bowed her head, ‘I do my best.’

‘I want cash up front. No argument,’ Louis said.

‘You’ll get paid on a Saturday morning, at the end of the week, you chancer,’ Rea answered back, then added, ‘No argument.’

He was still laughing when he picked up the two black sacks Rea had tied up ready for him. He hauled them over his shoulder. For a skinny lad, he was strong. ‘I’ll grab the ones out back in a minute,’ he said.

‘You eating enough, Louis?’ Rea asked, worried. His mother wasn’t a bad person, she realised. Just a bit flaky and far too preoccupied with her love life. But, there again, she was a single mum, so who was she to judge? She’d had George to help raise her two.

‘Yeah, yeah,’ Louis replied.

‘And are you doing your homework? You know it’s important you do well in your exams.’

‘Quit your nagging, you’re worse than me ma.’ But he was grinning. The truth was, he loved coming to Rea’s and loved her worrying about him. He didn’t get to see his grandma any more because his ma and her had fallen out.

‘Alright! I’ll shut up, for now. I’ll text you when they’re full again. And this time, I don’t care how busy you are, don’t leave me waiting.’

‘Mam say’s you’re weird, you know.’ He looked back over his shoulder as he opened the back door.

‘A lot do,’ Rea replied.

‘She doesn’t get why you never go out. You don’t, do you? Go out any more?’

What was there to say in response to that?

‘None of your beeswax. See you in a few days.’ And she slammed the back door shut as she shooed him out.

Explaining why she didn’t go out any more was difficult. She didn’t really understand it herself and, in her experience, when she tried to explain it to family and friends, they understood it less.

The fear, the panic at being outside, well, it sort of crept up on her. She hadn’t been herself for a long time. Not since Elise had left, really. George had thought she was depressed. She went to see her doctor and he told her it was normal. Empty-nest syndrome. Most went through it. Then, of course, came the grief. It took over everything. Then one day, while she was out doing the weekly shopping in Clare Hall, her first big panic attack happened. The shopping mall began to vibrate. One minute she was standing in Tesco trying to decide whether she fancied real butter or low-low, when something shifted. Inside of her. And around her. The lights that lined the cool fridge grew too bright and jarred her eyes. She remembered stepping back from it, dropping the butter onto the floor, a dull thud resounded as it made impact. Her vision then blurred and floaties danced around her eyes, making her head spin. It was like being sea-sick and hungover all at once.