Полная версия

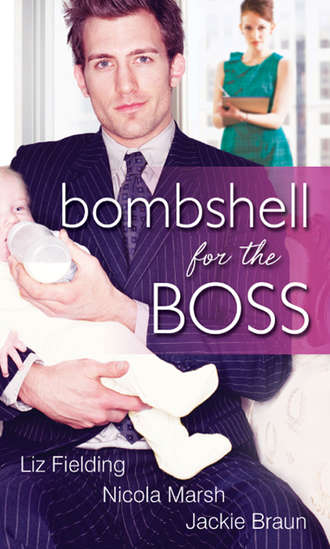

Bombshell For The Boss: The Bride's Baby

Realising that both Geena and Tom were looking at her a little oddly, she said, ‘I’m an adult. I don’t need anyone to give me away.’

‘Oh, right … Well, whatever. It’s your wedding. So you’re poised to walk up the aisle.’ Geena picked up the violets, pressed them into her hand. ‘Okay, the organ strikes up, you hear the rustle as everyone in the church gets to their feet. This is it. Da da da-da …’ she sang. ‘You’re walking up the aisle. Walk, walk,’ she urged, pushing her towards Tom. ‘Everyone is looking at you. People are sighing, but you don’t see them, don’t hear them,’ she went on relentlessly. ‘Everything is concentrated on the only two people in the church who matter. You, in the dress of your dreams,’ she said. ‘And him.’

She met Tom McFarlane’s gaze.

Why was he still there? Why hadn’t he just turned around and walked out? He didn’t have to stay …

‘What does it feel like as you move, Sylvie?’ Geena murmured, very softly, as if they were truly in church. ‘Cool against your skin? Can you feel the drag of a train? Can you hear it rustle? Tell me, Sylvie. Tell me what you’re feeling. Tell me what he’s seeing …’

For a moment she was there in the cool church with the sun streaming in through the stained glass. Could feel the dress as it brushed against her legs. The antique lace of her grandmother’s veil …

Could see Tom McFarlane standing in the spangle of coloured light, looking at her as if she made his world whole as she walked down the aisle towards him, a simple posy of violets in her hand.

‘Tell me what he’s seeing that’s making him melt,’ Geena persisted.

His gaze dropped to the unmistakable bulge where his baby was growing beneath her heart and, shattering the illusion, said, ‘Sackcloth and ashes would do it.’ Then, turning abruptly away, ‘Mark, have you got everything you need in here?’

He didn’t wait for an answer but, leaving the architect to catch up, he walked out, as if being in the same room with her was more than he could bear.

Mark, his smile wry, said, ‘Nice one, Geena. If you need any help getting your foot out of your mouth I can put you in touch with a good osteopath.’ Then, ‘Good meeting you, Sylvie.’

Geena, baffled, just raised a hand in acknowledgement as he left, then said, ‘What on earth was his problem?’

Sylvie, reaching for the table as her knees buckled slightly, swallowed, then, forcing herself to respond casually, said, ‘It would have been a good idea to have asked where we met.’

When she didn’t rush to provide the information, Geena gestured encouragingly. ‘Well? Where did you meet?’

‘I went to school with the woman he was going to marry, so I was entrusted with the role of putting together her fantasy wedding. I did try to warn you.’

‘But I was too busy talking. It’s a failing,’ she admitted. ‘So what was with the sackcloth and ashes remark? What did you do—book the wrong church? Did the marquee collapse? The guests go down with food poisoning? What?’

‘The bride changed her mind three days before the wedding.’

‘You’re kidding!’ Then, glancing after him, ‘Was she crazy?’

‘Rather the opposite. She came to her senses just in time. Candy Harcourt?’ she prompted. Then, when Geena shook her head, ‘You don’t read the gossip magazines?’

‘Is it compulsory?’

Sylvie searched for a laugh but failed to find one. He knew and she’d seen his reaction.

While there had been only silence, she had been able to fool herself that he might, given time, come round. Not any more.

It couldn’t get any worse.

‘No, it’s not compulsory, Geena, but in this instance I rather wish you had.’

‘I still don’t understand his problem,’ she said, frowning. ‘You can’t be held responsible for the bride getting cold feet.’

‘She eloped with one of my staff.’

‘Ouch.’ She shrugged. Then, as the man himself walked across the lawn in front of the window, ‘I still think that taking it out on you is a little harsh and if I didn’t have my own fantasy man waiting at home I’d be more than happy to give him a talking to he wouldn’t forget in a hurry. Although, to be honest, from the way he looked at you—’

‘I believe the expression “if looks could kill” just about covers it,’ Sylvie cut in quickly, distracting Geena before she managed to connect the dots.

‘Only if spontaneous combustion was the chosen method of execution. Are you sure it was only the bride who fell for the wedding planner?’ she pressed. Then perhaps realising just what she was saying, she held up her hands, in a gesture of apology. ‘Will you do me a favour and forget I said that? Forget I even thought it. How bad would it be for business if brides got the impression they couldn’t trust you with their grooms?’

‘What? No!’ she declared, but felt the betraying heat rush to her cheeks.

Geena didn’t pursue it, however—although she had an eyebrow that spoke volumes—just said, ‘My mistake.’ But not with any conviction—she was clearly a smart woman. Her sense of self-preservation belatedly kicked in, however, and she said, ‘Okay, forget Mr Hot-and-Sexy for the moment and just tell me what you saw.’

‘Saw?’

‘Just now. I was watching you. You saw something. Felt something.’

What she’d seen was the image that Geena had put into her head. Her nineteen-year-old self dressed in her great-grandmother’s wedding dress, the soft lace veil falling nearly to her feet.

The only difference being that in her fantasy moment it hadn’t been the man she’d been going to marry standing at the altar.

It had been Tom McFarlane who, for just a moment, she’d been certain was about to reach out and take her hand …

‘Sylvie?’

‘Yes,’ she said quickly. ‘You’re right. I was remembering something. A dress …’

Concentrate on the dress.

‘Are you really going to be able to make something from scratch in a few days?’ she asked a touch desperately. ‘Normally it takes weeks. Months …’

‘Well, I admit that it’s going to be a bit of a midnight oil job, but this is the world’s biggest break for me and everyone in the workroom is on standby to pull out all the stops to give you what you want.’ Then, ‘Besides, since you’re not actually going to be walking up the aisle in it—at least not this week—it wouldn’t actually matter if there was a strategic tack or pin in place for the photographs, would it?’

‘That rather depends where you put the pins!’

‘Forget the pins. Come on,’ she urged. ‘This is fantasy time! Indulge yourself, Sylvie. Dream a little. Dream a lot. Give me something I can work with …’

Those kind of dreams would only bring her heartache, but this was important for Geena and she made a determined effort to play along.

‘Actually, the truth is not especially indulgent,’ she said with a rueful smile. ‘Or terribly helpful. I did the fantasy for real when I was nineteen. On that occasion the plan was to wear my great-grandmother’s wedding dress.’

‘Really? Gosh, that’s so romantic.’

Yes, well, nineteen was an age for romance. She knew better now …

‘So, let’s see. We’re talking nineteen-twenties? Ankle-bone length? Dropped waist? Lace?’ She took out a pad and did a quick sketch. ‘Something like that?’

‘Pretty much,’ she said, impressed. ‘That’s lovely.’

‘Thank you.’ Then, shaking her head. ‘You are so lucky. How many people even know what their great-grandmother was wearing when she married, let alone still have the dress? You have still got it?’

About to shake her head, explain, Sylvie realised that it was probably just where she’d left it. After all, nothing else seemed to have been touched.

But that was a step back to a different life. A different woman.

‘I’m supposed to be displaying your skills, Geena,’ she said. ‘Giving you a showcase for your talent. A vintage gown wouldn’t do that.’

‘You’re supposed to be giving the world your personal fantasy,’ Geena reminded her generously. ‘Although, unless it’s been stored properly, it’s likely to be moth-eaten and yellowed. Not quite what Celebrity are expecting for their feature. And, forgive me for mentioning this, but I don’t imagine your great-grandmother was—how do they put it?—in an “interesting condition” when she took that slow walk up the aisle.’

‘True.’ The dress had been stored with care and when she’d been nineteen it had been as close to perfect as it was possible for a dress to be. Life had moved on. She was a different woman now and, pulling a face, she said, ‘Rising thirty and pregnant, all that virginal lace would look singularly inappropriate.’

‘Actually, I’ve got something rather more grown-up in mind for you,’ she replied. ‘Something that will go with those shoes. But I’d really love to see your grandmother’s dress, if only out of professional interest.’

‘I’ll see what I can do.’

‘Great. Now, hold still and I’ll run this tape over you and take some measurements so that we can start work on the toile.’

CHAPTER SIX

MARK HILLIARD didn’t say a word when Tom joined him, but then they’d known one another for a long time. A look was enough.

‘I’m sorry about that. As you may have realised, there’s a bit of … tension.’

‘Sackcloth and ashes? If that’s tension, I wouldn’t like to be around when you declare open war.’ Mark’s smile was thoughtful. ‘To be honest, it sounded more like—’

‘Like what?’ he demanded, but the man just held up his hands and shook his head. But then, he didn’t have to say what he was thinking. It was written all over his face. ‘It was a business matter,’ he said abruptly. Which was true. ‘Nothing else.’ Which was not.

Sackcloth and ashes.

That wasn’t like any business dispute he’d ever been involved in. It was more like an exchange between two people who couldn’t make up their minds whether to throttle one another or tear each other’s clothes off.

Which pretty much covered it. At least from his viewpoint, except that he hadn’t wanted to feel that way about anyone. Out of control. Out of his mind. Racked with guilt …

She had clearly wasted no time in putting him out of her mind. But he could scarcely blame her for that. He’d walked away, hadn’t written, hadn’t called, then messed up by asking his secretary to send her a cheque for the full amount of her account. Paid in full. No wonder she’d sent the money back.

And then, when he’d been ready to fall at her feet, grovel, it had been too late.

But six months hadn’t changed a thing. Sylvie Smith still got to him in ways that he didn’t begin to understand.

And he was beginning to suspect, despite the fact that she was expecting a baby with her childhood sweetheart—and he tried not to think about how long that relationship had been in existence, whether it was an affair with her that had wrecked the new Earl’s marriage—it was the same for her.

The truth of the matter was that, even in sackcloth, she would have the ability to bring him to meltdown. Which was a bit like getting burned and then putting your hand straight back in the fire.

But as she’d stood there while that crazy female went on about the village church, about walking up the aisle, about someone standing at the altar—about him standing at the altar—he’d seen it all as plainly as if he’d been there. Even the light streaming through a stained glass window and dancing around her hair, staining it with a rainbow of colours.

He’d seen it and had wanted to be there in a way he’d never wanted that five-act opera of a wedding, unpaid advertising in the gossip magazines for Miss Sylvie Duchamp Smith that Candy had been planning.

A small country church with the sweet scent of violets that even out here seemed to cling to him instead of some phoney show-piece. A commitment that was real between two people who were marrying for all the right reasons.

So real, in fact, that he’d come within a heartbeat of reaching out a hand to her.

Maybe Pam was right. He should go back to London until this was all over. Except he knew it wouldn’t help; at least here he would be forced to witness her making plans for her own wedding. The ‘blooming’ bride. Blooming, glowing …

Euphemisms.

The word was pregnant.

If nothing else did it, that fact alone should force him to get a grip on reality.

Realising that Mark was looking at him a little oddly, he turned abruptly and began to walk towards the outbuildings.

‘Let’s take a look at the coach house and stable block,’ he said briskly.

Pregnant.

‘I think we could probably get a dozen accommodation units out of the buildings grouped around the courtyard,’ Mark said, falling in beside him.

‘That sounds promising. What about the barn?’

‘There are any number of options open to you there. It’s very adaptable. In fact, I did wonder if you’d like to convert it into your own country retreat. There’s a small private road and, with a walled garden, it would be very private.’

If it had been anywhere else, he might have been tempted. But Longbourne Court was now a place he just wanted to develop for maximum profit so that he could eradicate it from his memory, along with Sylvie Smith.

The last thing Sylvie had done before she’d left Longbourne Court was to pack the wedding dress away where it belonged, in a chest in the attic containing the rest of her great-grandmother’s clothes.

Not wanted in this life.

It was going to be painful to see it again. To touch it. Feel the connection with that part of her which had been packed away with the dress.

Always supposing the chests and trunks were still there.

There was only one way to find out, but Longbourne Court was no longer her home; she couldn’t just take the back stairs that led up to the storage space under the roof and start rootling around without as much as a by-your-leave.

But as soon as she’d talked to Josie, reassured herself that everything was running smoothly in her real life, she went in search of Pam Baxter, planning to clear it with her. Get it over with while Tom McFarlane was still safely occupied with the architect.

She’d seen him from the window. Had watched him walking down to the old coach house with Mark Hilliard.

He’d shaved since their last encounter. Changed. The sweater was still cashmere, but it was black.

Like his mood.

And yet he’d had a smile for Geena. The real thing. No wonder the woman had been swept away.

It had been that kind of smile.

The dangerous kind that stirred the blood, heated the skin, brought all kinds of deep buried longings bubbling to the surface.

Not that he’d needed a smile to get that response from her. He’d done it with no more than a look.

But then there had been that look, that momentary connection across Geena’s head when, for a fleeting moment, she’d felt as if it were just the two of them against the world. When, for a precious instant, she’d been sure that everything was going to be all right.

No more than wishful thinking, she knew, as she watched a waft of breeze coming up from the river catch at his hair. He dragged his fingers through it, pushing it back off his face before glancing back at the house, at the window of the morning room, as if he felt her watching him.

Frowning briefly before he turned and walked away, leaving Mark to trail in his wake.

She slumped back in the chair, as if unexpectedly released from some crushing grip, and it took all her strength to stand up, to go and find Pam.

The library door was open and when she tapped on it, went in, she discovered the room was empty.

She glanced at her watch, deciding to give it a couple of minutes, crossing without thinking to the shelves, running her hand over the spines of worn, familiar volumes. Everything was exactly as she’d left it. Even the family bible was on its stand and she opened it to the pages that recorded their family history. Each birth, marriage, death.

The blank space beneath her own name for her marriage, her children—that would always remain empty.

The last entry, her mother’s death, written in her own hand. After all her mother had been through, that had been so cruel. So unfair. But when had life ever been fair? she thought, looking at the framed photograph standing by itself on a small shelf above the bible.

It was nothing special. Just a group of young men in tennis flannels, lounging on the lawn in front of a tea table on some long ago summer afternoon.

She wasn’t sure how long she’d been standing there, hearing the distant echo of her great-grandfather’s voice as he’d repeated their names, a roll-call of heroes, when some shift in the air, a prickle at the base of her neck, warned her that she was no longer alone.

Not Pam. Pam would have spoken as soon as she’d seen her.

‘Checking up on me, Mr McFarlane?’ she asked, not looking round, even when he joined her. ‘Making sure I’m not getting too comfortable?’

‘Who are these people?’ he asked, his voice grating as, ignoring the question, he picked up the photograph and made a gesture with it which—small though it was—managed to include the portraits that lined the stairs, the upper gallery, that hung over fireplaces.

She waited, anticipating some further sarcasm, but when she didn’t answer he looked up and for a moment she saw genuine curiosity.

‘Just family,’ she said simply.

‘Family?’ He looked as if he would say something more and she held her breath.

‘Yes?’ she prompted, but his eyes snapped back to the photograph.

‘Didn’t they have anything better to do than play games?’ he demanded. ‘Laze about at tea parties?’

Her turn to frown. Something about the photograph disturbed him, she could see, but she couldn’t let him get away with that dismissive remark.

Laying a finger on the figure of a young man who was smiling, obviously saying something to whoever was taking the photograph, she said, ‘This is my great-uncle Henry. He was twenty-one when this was taken. Just down from Oxford.’ She moved to the next figure. ‘This is my great-uncle George. He was nineteen. Great-uncle Arthur was fifteen.’ She leaned closer so that her shoulder touched his arm, but she ignored the frisson of danger, too absorbed in the photograph to heed the warning. ‘That’s Bertie. And David. They were cousins. The same age as Arthur. And this is Max. He’d just got engaged to my great-aunt Mary. She was the one holding the camera.’

‘And the boy in the front? The joker pulling the face?’

‘That’s my great-grandfather, James Duchamp. He wasn’t quite twelve when this was taken. He was just short of his seventeenth birthday four years later when the carnage that they call The Great War ended. The only one of them to survive, marry, raise a family.’

‘It was the same for every family,’ he said abruptly.

‘I know, Mr McFarlane. Rich and poor of all nations died together by the million in the trenches.’ She looked up. ‘There were precious few tennis parties for anyone after this was taken.’

Tom McFarlane stared at the picture, doing his best to ignore the warmth of her shoulder against his chest, the silky touch of a strand of hair that had escaped her scarf as it brushed against his cheek.

‘For most people there never were any tennis parties,’ he said as, incapable of moving, physically distancing himself from her, he did his best to put up mental barriers. Then, in the same breath, ‘Since we appear to be stuck under the same roof for the next week, it might be easier if you called me Tom. It’s not as if we’re exactly strangers.’ Tearing them down.

‘I believe that’s exactly what we are, Mr McFarlane,’ she replied, cool as the proverbial cucumber. ‘Strangers.’

He nodded, acknowledging the truth of that. The lie of it. ‘Nevertheless,’ he persisted and she glanced up, her look giving the lie to her words as she met his gaze, as if searching for something … ‘Just to save time,’ he added.

‘To save time?’

She didn’t quite shrug, didn’t quite smile—or only in self-mockery, as if she’d hoped for something more. What, for heaven’s sake? Hadn’t she got enough?

‘Very well,’ she said. ‘Tom it is. On the strict understanding that it’s just to save time. But you are going to have to call me Sylvie. My time may not be as valuable as yours, but it’s in equally short supply.’

‘I think I can manage that. Sylvie.’

Divorced from ‘Duchamp’ and ‘Smith’, the name slipped over his tongue like silk and he wanted to say it again.

Sylvie.

Instead, he cleared his throat and focused on the photograph.

‘Why is this here?’ he asked. ‘Didn’t you want it?’ Then, because if this had been a photograph of his family, he would never have let it go, ‘It’s part of your family history.’

Sylvie took the photograph from him. Laid her hand against the cold glass for a moment, her eyes closed, remembering.

‘When the creditors moved in,’ she said after a moment, ‘all I was allowed to take were my clothes and a few personal possessions. The pearls I was given by my grandfather for my eighteenth birthday. And my car, although they insisted on checking the log book to make sure it was in my name before they let me drive away.’

It should have mattered. But by then nothing had mattered …

‘You’ll understand if I save my sympathy for the people who were owed money.’

She looked up at him. So solid. So successful. So scornful.

‘You needn’t be concerned for the little men,’ she said. ‘We always paid our bills. Our problems were caused by two lots of death duties in three years and the fact that my grandfather, after a lifetime of a somewhat relaxed attitude to expenditure, had decided to think of the future, the family and, on the advice of someone he trusted, had become a Lloyds “name” a couple of years before everything went belly-up.’

A fact which, when he realised what it meant, had certainly contributed to the heart attack that had killed him and, indirectly, to the death of her mother.

‘The irony of the situation is that if he’d carried on throwing parties and letting the future take care of itself we’d all have been a lot better off,’ she added.

‘But this photograph doesn’t have any value,’ he protested. ‘Beyond historical interest. Sentimental attachment.’

‘Yes, well, they did say that once a complete inventory had been taken I would be allowed to come back, take away family things that had no intrinsic value. But then a world-famous rock star who’d visited the house as a boy was seized by a mission to conserve the place in aspic as a slice of history.’

Tom McFarlane made a sound that suggested he was less than impressed.

‘I know. More money than sense, but he made an offer that the creditors couldn’t refuse and, since he was prepared to pay a very large premium for his pleasure, he got it all. Family photographs, portraits, all the junk in the attic. Even Mr and Mrs Kennedy, the housekeeper and man of all work, were kept on as caretakers, so it wasn’t all bad news.’

‘Could they do that? Sell everything?’

‘Who was to stop them? I didn’t have any money to fight for the rights to my family history and, even if I did, the only people to benefit would have been the lawyers. This way everything was settled. Was preserved.’

And she’d been able to move on, make another life instead of every day being reminded of things she’d rather forget.

Jeremy putting off the wedding—just until things had settled down. Her mother’s determination to confront the people who were draining everything out of her family home. Her father … No, she refused to waste a single thought on him.

‘I’d moved into a flat share with two other girls by then and had barely enough room to hang my clothes, let alone the family portraits.’ She took the photograph from him and replaced it on the shelf where it had been all her life. All her mother’s life. All her grandfather’s life too. ‘Besides, you’re right. This isn’t just my history. As you said, it was the same for everyone.’