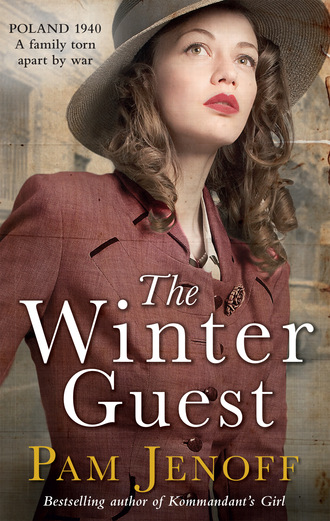

Полная версия

The Winter Guest

“People wouldn’t stand for it,” she replied to Ruth, resuming their conversation in that fractured way that happened frequently while they were caring for the children. A lack of confidence eroded her voice. In fact, the war had stripped away so many civilities, given people a license to act on their deeper, baser selves. Many, she suspected with an uneasy feeling, would be only too happy to let the Germans get rid of not just Jews but neighbors they had never really wanted in the first place.

Helena’s eyes traveled to the corner by the fireplace, where the scarf Ruth had knitted for Piotr still lay crumpled in a ball, untouched though months had passed. She kicked it out of the way, hoping Ruth had not seen. Anger rose within her as she thought of the boy who had broken her sister’s heart. “He’s not worth it,” she had wanted to say many times since Piotr last had come. But she held back, knowing such sentiments would only bring Ruth more pain.

Helena gestured to Karolina’s thick hair, which Ruth had cowed earlier into two luminous pigtails. Karolina was the outlier in their auburn-haired cluster—thick locks the color of cornstalks made her shine like the sun. “Do mine next?” she asked.

“Really?” Ruth’s brow lifted. Helena held her breath, wondering if she’d gone too far. She’d never had the patience to sit, instead pulling her hair into a scraggly knot at the back of her neck. She worried that this, coupled with her announcement of an extra visit to their mother, might arouse Ruth’s suspicion. But Ruth just shrugged. “Sit down.” Helena dropped into the chair. Ruth’s touch was gentle, her movements soothing as she coaxed the stubborn wisps into place with deft fingers. Helena fought the urge to fidget—it was all she could do not to leap from the chair and run out the door into the forest.

“Mischa needs shoes,” she announced grimly when Ruth had finished braiding. Ruth’s brow wrinkled. For the girls, there was always an old pair to be handed down, but Michal would not be big enough to wear Tata’s boots for at least another year or two, and there was no money for new ones. “What about your knitting? You could sell some pieces.”

Ruth cocked her head, as if she had not considered that her handiwork would have value to anyone outside of the house. “Perhaps with Christmas coming I can barter something knitted for a pair at market.”

Christmas. The word sounded foreign, as if from another lifetime. “Remember how Mama would decorate the house with mistletoe?”

“Holly,” her sister corrected, her voice crackling with authority. With Ruth, there was always a rejoinder. “And we would sing carols until she would give us a coin to stop.” Helena smiled fondly at the memory, one of many that only she and Ruth shared. “Then we would open our gifts and Tata would pretend to fall asleep early...”

“He didn’t...” Helena began. Tata hadn’t pretended to sleep; he had passed out from the half bottle of homemade potato vodka he consumed during Wigilia, their Christmas Eve feast. Even as a young child, Helena had known the truth. How could two people live the same moment but remember it so differently?

“Of course he did,” she relented, allowing Ruth to win. Ruth sniffed with quiet satisfaction.

Helena brushed aside the memories, forcing herself to focus on more practical matters. “Or we could sell it,” she said, gesturing with her head toward the corner. The sewing machine, which Tata had bought for their mother as a wedding present, had been her most prized possession. It would fetch a fair price, even from someone who wanted to use the parts for scrap.

“No!”

“Ruti, we must be practical. We need food and coal.”

But Ruth shook her head. “We need it. That’s why Mama left it to me. She knew you wouldn’t keep it safe.”

A lump of anger formed in Helena’s throat. Had Mama actually bequeathed the sewing machine to Ruth while she was still coherent enough? More likely, Ruth had simply presumed. Helena swallowed, struggling not to retort. Ruth clung to the machine because letting it go meant acknowledging that things had changed permanently, and that Mama was not coming back.

Helena walked back to the fireplace where Karolina played by the hearth. “Let’s get you dressed.” She held out her arms, but the child hung back, looking up uncertainly at Ruth. It was Ruth from whom the children sought care and affection, preferring her softer voice and gentle, uncalloused hands.

Ruth crossed the room gracefully, appearing to swirl rather then walk, her skirt a gentle halo around her—not like Helena, who seemed to crash headlong at full force. She scooped Karolina up with effort. “She’s getting too old to be carried all of the time,” Helena scolded. “You’ll spoil her.” Ruth did not reply, but smiled sweetly, smoothing her hair and kissing the top of her head. Dorie and Karolina had had so much less of their parents than the others. Ruth tried to make up for it, fashioning little treats when she could and singing to them and rocking them at night. Karolina eyed Helena reproachfully now as Ruth carried her past. Helena opened her mouth, searching for the right words. She loved the children, too, though perhaps she never told them as much. But they needed to be strong in these times.

Helena walked past her sisters to the bedroom. Fingering the stain on her sleeve, Helena’s eyes roamed longingly toward the armoire. She opened the door. Mama’s clothing still hung neatly, as clean and pressed as the day she had gone to the hospital. Her church dress was practically new, the gleaming buttons kept immaculately. Even her two everyday dresses were nicer that Helena’s, having been spared the hardships of the woods these many months.

Helena reached inside and pulled one of the dresses out. She remembered Christmas two years earlier, when Ruth had opened a box to reveal a new skirt, pink and crisp. “There was only money for one,” Mama explained. “And Ruth’s bigger. You’ll have her old one.” It had been a pretext. Though Ruth was a bit fuller figured, the truth was that she was the prettier one with the better chance of marriage, and it was always presumed that she should have the nicer, more feminine things. There had never been any talk of a suitor for Helena, even in happier times.

“What are you doing?” Helena jumped and spun around. Ruth had appeared behind her, stealthily as a cat.

Helena held up the dress. “I was thinking of borrowing this.”

“Nonsense,” Ruth snapped. “Yours is good enough for traipsing through the woods and doing chores. You’d only soil it and we need to leave it for when Mama comes home.” She eyed Helena warily, daring her to argue. Then Ruth took the dress from her and returned it to the armoire, closing the door firmly behind her.

5

The sun was dropping low to the trees later that afternoon as Helena neared the chapel and pushed open the door. “Dzie´n dobry...?” she called into the dank semidarkness. Silence greeted her. Surely the soldier could not have fled in his condition. For a second, she wondered if she’d imagined him. He could be dead, she thought with more dismay than she should have felt for someone she’d only met once. His wounds had seemed serious enough.

She pulled back the shutter that covered one of the broken windows to allow the pale light to filter in. The soldier was curled up in a tight ball on the ground, much as he had been when she found him, but farther from the door. She hesitated as excitement and alarm rose in her. What was she thinking by coming here? She didn’t know this man, or whether he was here to help or do harm.

Helena walked over and knelt to feel his cheek, caught off guard by the softness of his skin. She was relieved to find he was still warm. Then she remembered Karolina’s illness, barely passed. Had she made a mistake by coming and possibly bringing sickness to this man in his already-weakened state?

The soldier moved suddenly beneath her hand and she jumped. His eyes snapped open. He stiffened, almost as Mama had when she feared pain in the hospital.

“It’s okay,” Helena said, holding her hands low and open. “I’m the one who brought you here.”

He forced himself to a sitting position, trying without success to stifle a whimper. “Who are you?” His Polish was stiff and a bit accented.

“I’m called Helena. I live close to the village. You should rest,” she added.

But he sat even straighter, clenching and unclenching his hands. His chocolate eyes, set just a shade too close together, darted back and forth. “Does anyone else know that I’m here?”

“Not that I’m aware,” she replied quickly. “I haven’t told anyone.” She wanted to say that someone else might have heard the crash, but it seemed unwise to upset him more.

He stared at her, disbelieving. “Are you sure?”

“I haven’t told anyone,” she repeated, suddenly annoyed. “Why would I have gone to all of the trouble to save you just to turn you in?”

He shrugged, somewhat calmer now. “A reward, maybe. Who knows why people do anything these days?”

“No one knows that you’re here,” she replied, her voice soothing.

“Where is ‘here’ exactly?” he asked.

“Southern Poland, Małopolska. You’re about twenty kilometers from the city.”

“Kraków?” Helena nodded, sensing from his expression that her answer was not what he expected. “That puts us about an hour from the southern border, doesn’t it?”

“Roughly, yes. Perhaps a bit more.”

His face relaxed slightly. “You’re real.” She cocked her head. “I thought I might have been delirious and dreamed you. And then I wasn’t sure you were coming back.”

“I’m sorry,” she replied quickly. “It’s hard to get away.” He had rugged features, an uneven nose and a chin that jutted forth defiantly. But his eyelashes were longer than she knew a man could have, and there was a softness to his gaze that kept him from being too intimidating.

“I didn’t mean it that way,” the man added. “Just that I’m glad to see you again.” A warm flush seemed to wash over her then, and she could feel her cheeks color. “I don’t think I introduced myself properly. Sam Rosen.” He held out his hand. “I’m American.” His deep voice had a lyrical quality to it, the words nearly a song.

“But you’re speaking Polish.”

“Yes, my grandparents were from one of those eastern parts by the border that was Poland when it wasn’t Russia. They used to speak Polish with my mother when they didn’t want the children to understand what they were saying. So I had a reason to try to figure it out.” The corners of his mouth rose with amusement.

She shook his outstretched hand awkwardly. He had wiped the blood from his face, she noticed, leaving a narrow gash across his forehead. “You’re looking better,” she remarked, meaning it. There was a ruddiness to his complexion that had not been there before. His hair was darker than she remembered it, almost black. A healed scar ran pale and deep from the right corner of his mouth to his chin.

“Thanks to you,” he replied, his eyes warm. “Bringing me here saved my life. And the food you left did me a world of good.” He made it sound as though she had left him an entire feast and not just a handful of bread.

“A bit more,” she said, passing him another piece of bread, slightly larger. His fingers brushed against her own, coarse and unfamiliar. “I’m sorry that’s all I could manage.” She could not take any of the scarce sheep’s cheese or lard they needed for the children.

“You’re very kind.” His voice was full with gratitude. He tore into the bread with an urgency that suggested true hunger. Of course, the morsel she’d left him last time would not have lasted a day, once he was able to eat. She noticed then a pile of leaves—he must have dragged himself outside to forage. “They taught us in training which things we could eat, roots and such. And I’ve managed to drink some rainwater.” He gestured across the chapel to a puddle that had formed where it had rained through the opening in the roof. “I’m sorry not to get up,” he added. “My leg is still a mess. But I don’t think it needs to be set.”

She looked around the chapel—the wooden pews had rotted to the floor and there was no sign of any pulpit, but fine engravings were still visible on the walls, faded images of angels and the Virgin Mary at the front. “It’s a good thing I found you,” she said, sounding more pleased with herself than she intended. “The path is just off the main road. Someone else might have turned you in to the police for favors or food.”

“What about animals?” he asked. “Are there wolves?”

She hesitated. “Yes.” His eyes widened. She did not want to alarm him, but other than sparing Ruth the occasional bit of reality, it was not in Helena’s nature to lie. Once the wild animals had clung to the high hills, content to feed on small prey. But with food sources growing scarce, they’d become bolder, venturing down to the outskirts of the village to steal livestock.

“Here.” Helena opened her bag. She had looked around the hospital ward while visiting her mother earlier, searching for whatever supplies she could take to help him. There had only been a few rags and a small bottle of alcohol lying on one of the nurse’s carts and she didn’t dare to risk looking in the supply closet or any of the cupboards. She handed the bottle to him. “I brought you these, too.” She pulled out the wool coat and thick gray sweater that had been her father’s. Sam took the sweater and put it on, swimming in its massive girth. She hoped he could not detect the smell of liquor that lingered, even after it had been washed.

“Thank you. My jacket must have been stripped off with the parachute. It’s probably hanging from a tree somewhere.”

So he had fallen from the sky, after all. “So you jumped?”

He nodded. “Before the plane crashed. The weather forced us to fly farther north than we should have, I think, and the pilot had to go off course. At first we received orders to turn back, but we had all agreed that we were too far gone for that—we wanted to see the mission through. Then something went wrong with the plane. We knew we were going to have to wild jump, that means just land anywhere, as well as we could.” She imagined it, leaping from the plane in darkness and mist, not knowing what lay below. “I wasn’t sure my chute was going to have time to open. It did, but I got caught in a tree. When I was trying to free my chute, I fell from the tree and, well...” He gestured to his leg. “The rest you know.”

Sam opened the bottle and doused the cloth, then pressed it against the gash on his forehead, grimacing. He shivered and there was a sudden air of vulnerability about him, as though all of the foreign bits had been stripped away.

“I’ll be right back,” she announced. Before he could respond, Helena rushed outside to the grassy patch above the chapel, collecting an armful of sticks to make a fire. She stopped abruptly. What was she doing coming to the woods to tend to this stranger, risking discovery at any moment? Caretaking had never been in her nature. It was Ruth who nurtured the others, Michal that cared for small, hurt animals. And she had her family’s well-being to think about. She had done enough, too much, her sister would surely say.

Helena eyed the path back toward the village. She could just turn and go, now. But then she remembered the gratitude in the soldier’s eyes as he had taken the food from her. She was his only hope. If the Germans came, though, she would be arrested, leaving her family helpless. She had to think of them first. One had to be practical in order to survive in these times. She would build the soldier a fire before going and that was all.

She returned with her armful of kindling, which she carried to the small stove in the corner. He frowned. “It isn’t right, you hauling wood for me.”

Helena fought the urge to laugh. She carried enough wood to keep her family warm—the small pile of kindling was nothing. Still, she was touched by his concern. “It’s fine.” The wood was too damp, she fretted as she broke it into pieces. But when she struck the match she’d brought from home and touched it to the pile, it began to burn merrily.

“Thank you,” Sam said, sliding closer along the floor as she closed the grate. The tiny flames seemed to make his dark eyes dance. He winced.

“Is it very painful?” she asked.

“It isn’t so bad when I’m still, but when I move, it’s awful.”

“Let me.” She walked to him and slowly helped him inch closer to the fire, letting him lean on her for support, feeling his muscles strain with the effort of each movement.

“There is one other thing...” He hesitated. “I’m so sorry to ask, but I’d like to wash if that’s somehow possible.” She’d noticed it earlier, his own masculine earthy scent, stronger than it had been last time she was here. “Perhaps some water?”

“Let me see what I can find.” Helena went back outside to where she had seen a rusty bucket lying by the drain. She picked up the bucket and walked uphill several meters to the stream. She moved slowly on her return, taking care not to spill. “It’s cold,” she cautioned as Sam took it from her, his hand brushing hers.

He cupped his hand and drank from the bucket hurriedly. Then he splashed the water on his face, not seeming to mind as the icy droplets trickled down his neck. “That feels great.”

He pulled off the sweater and unbuttoned his shirt. She blushed and half turned away; out of the corner of her eye she caught a glimpse of his back where it met his shoulder, muscle and bone working against the bare, pale skin as he bathed. She sucked in her breath quickly, then held it, hoping he hadn’t heard.

Her heart hammered against her ribs. “Pan Rosen...” she began, lowering herself to the ground as he dried himself with his torn shirt.

“Sam,” he corrected. Sam. In that moment, he was not a soldier, but a man, with an open face and broad smooth cheeks she wanted to touch. He pulled on the sweater she had given him once more. “And may I call you Hel...” He faltered.

“Helena,” she prompted.

“Helena,” he repeated, as if trying it on for size. “That’s quite a mouthful. May I call you Lena?”

“Y-yes,” she replied, caught off guard. All of the other children had pet names, Ruti, Mischa—but she had always been Helena.

“Lena,” he said again, a slight smile playing at the corners of his lips. His shoulders were broad, forearms strong. Sitting beside him, she felt oddly small and delicate.

She struggled to remember what she wanted to say. “What are you doing here, Sam? Are the Americans coming to help us?”

“No.” Her heart sank. The talk of the Americans entering the war had been growing in recent months, whispered everywhere from the hospital corridors to the market in the town square. And if the Americans weren’t coming yet, then what was he doing here? “That is, I mean...” He broke off. “I really can’t say too much,” he added apologetically. Then he frowned again. “You must be taking a terrible risk coming here.”

Not really, she wanted to say, but that would be untrue. “Everything is dangerous now,” she replied instead. In truth, finding him was the most exciting thing that had happened to her in years, maybe ever, and she had been eager to return. “Especially going to see my mother.” She told him then about sneaking in and out of Kraków, her near-encounter with the jeep. “Of course, if not for the German I would never have come this way and found you.” She could feel herself blush again.

He did not seem to notice, though, but continued staring at her, his brow crinkled. “I wish you wouldn’t go to the city again.”

Helena was touched by his concern, more than she might have expected from a man she just met. “That’s what my...” She stopped herself from telling him about Ruth, the fact that she had a twin. She did not want to acknowledge her prettier sister. “There are five children in the family, including me. I’m the one who has to go check on Mama. My father is gone and there’s no one else to make sure she’s cared for.”

Helena’s thoughts turned to her mother. She’d actually seemed better today. For once she’d been awake and hadn’t mistaken Helena for her sister. And she had reached for the bread that Helena offered. For a second, Helena had hesitated; she had hoped to keep the extra food for the soldier. She was overcome with shame and had quickly broken the bread and moistened it. “Pani Kasia says that they’re going to kill us,” Mama had announced abruptly as she chewed, gesturing to the woman in the bed next to hers. She had an unworried, slightly gossipy tone as though discussing the latest rumor about one of the neighbors back home.

Inwardly, Helena had blanched. She had worked so hard to shield Mama from the outside world. But the hospital was a porous place and news seeped through the cracks. “She’s a crazy old woman,” Helena replied carefully in a low voice. For months she had done her best to keep the truth from her mother without actually lying to her, and she didn’t want to cross that line now.

“And sour to boot,” Mama added, smiling faintly. There was a flicker of clarity to her eyes and for a second Helena glimpsed the mother of old, the one who had baked sweet cakes and rubbed their feet on frigid winter nights. There were so many things she wanted to ask her mother about her childhood and the past and what her hopes and dreams had been.

“Mama...” She turned back, then stopped. Her mother was staring out the window, once more the cloud pulled down over her face like a veil, and Helena knew that she was gone and could not be reached.

“It’s so brave of you to make that journey every week,” Sam said, drawing her from her thoughts. His voice was full with admiration.

“Brave?” She was unaccustomed to thinking of herself that way. “You’re the brave one, leaving your family to come all the way over here.”

“That’s different,” he replied, and a shadow seemed to pass across his face.

“How old are you, anyway?” she asked, hearing her sister’s phantom admonition that the question was too blunt.

“Eighteen.”

“Same as me,” she marveled.

“Almost nineteen. I enlisted the day after my birthday.”

“Did you always want to be a soldier?”

“No.” His face clouded over. “But I had to come.”

“Why?”

He bit his lip, not answering. Then he lifted his shoulders, straightening. “When I joined the army, they sent me to school in Georgia, that’s in the southern part of the United States, for nearly a year. I had to learn to be a soldier, you see, and then how to be a paratrooper.”

Helena processed the information. She had never thought about someone becoming a soldier; it seemed like they were already that way. But now she pictured it, Sam donning his uniform and getting his hair cut short. “Is that why it’s taking so long for the Americans to come?” It came out sounding wrong, as though she was holding him personally responsible for his country.

But he seemed to understand what she meant. “In part, yes.” His brow wrinkled. “Some people don’t want us to enter the war at all.” How could the Americans not help? Helena wanted to ask. Sam continued, “Everyone has to be trained, they have to plan the missions...” He paused. “I probably shouldn’t say too much. It’s nothing personal,” he hastened to add. “I’m not supposed to talk about it with anyone.”

“I understand.” But the moment hung heavy between them. She was a Pole and not to be trusted.

“They don’t know,” he explained earnestly. “I mean, the American people know about Hitler, of course, and the Jews there are concerned for their relatives, trying to get them out. Until I came to Europe, I had no idea...” He stopped abruptly.

“No idea about what?”

Sam bit his lip. “Nothing.” Helena could tell from his voice that there were things that she, even in the middle of it all, had not seen. Things he would not share with her. “Anyway, our rabbi back home said that—”

“You’re Jewish?” she interrupted. He nodded. She was surprised—he didn’t look anything like the Jews she’d seen in the city, shawl covered and stooped. But there was something unmistakably different about him, a slight arch to his nose, chin just a shade sharper than the people around here. His dark hair was curly and so thick it seemed that water could not penetrate it. “You don’t look it,” she blurted. Her face flushed. “That is, the Jews around here...”