Полная версия

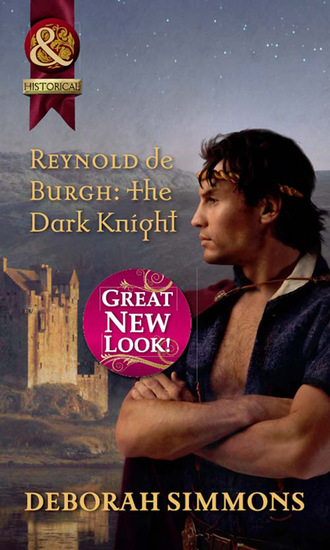

Reynold de Burgh: The Dark Knight

The only light was that from a sliver of moon that shone through the roofless remains, but it was enough to illuminate the heavy walking stick that hovered above Reynold’s head. Thebald loomed over him with the stout weapon at the ready, while the boy who had used it to hop about earlier was now standing upright without aid, going through Peregrine’s supplies. Had they already knocked the youth senseless?

The thought of Peregrine’s fate fuelled his strength, and Reynold leapt upwards with a roar. Although wiry and tenacious, Thebald was no match for a well-trained knight, and Reynold quickly wrested the cudgel from his hand even as the thief yelled for his companion. The boy, obviously no cripple, pulled a dagger and threw it with no little skill, a deadly missile carefully aimed at Reynold’s chest.

Apparently asleep, Peregrine had awoken at the noise and shouted a warning as he rose to his feet. Reynold spared him a glance only to see him felled by the young brigand, who fought with the ferocity of a demon. The two rolled around the remains of the fire, stirring it back to life.

Snatching up the knife that now stuck from his chest, Reynold put it to Thebald’s throat. ‘Call off your dog, if you value your life.’

Eyes bulging, the would-be thief struggled for breath. ‘Stop, Rowland. Stop!’ he croaked.

The young miscreant showed no signs of hearing or heeding, so Reynold struck Thebald with the walking stick, hard enough to prevent any further mischief, and turned his attention to the brawl that was now perilously close to the fire. It was obvious that the devil was trying to roll Peregrine into the embers in hopes of burning him or even setting him alight.

With a grunt, Reynold grabbed Rowland by the back of the neck and threw him on to the ground. Before he could rise, Reynold had put his own dagger to his throat.

‘Listen carefully, faux cripple, lest you lose your life. I am lame, and yet I can gullet you like a fish.’

Even when presented with the sight of his injured master, Rowland remained difficult. He would admit nothing, and struggled so that Reynold was forced to tie him up with a length of rope in his pack. And after Peregrine and Reynold had gathered up their belongings and mounted, taking the thieves’ horse with them, the youth railed at them, screaming curses into the night.

‘I cannot believe it,’ Peregrine murmured, obviously shaken by the encounter. ‘He seemed so gentle and kind this afternoon.’

‘Let that be a lesson to you, boy. Appearances can be deceiving.’

‘They could have killed us while we slept!’

‘You perhaps, but not I.’ When Peregrine ducked his head in embarrassment, Reynold softened his tone. ‘I think they are nothing more than common robbers who make a living by preying on pilgrims. Murder is probably only a last resort for them, else they would have killed us first and then picked our pockets.’

Peregrine did not look comforted. ‘But what about that knife? I saw it strike you in the chest! Are you not wounded, my lord?’

Reynold shook his head. ‘I would not go upon the roads without mail, though I’ve covered the short coat with my tunic so I don’t draw attention.’

‘But you will always draw attention.’

Dare the boy refer to his leg? Reynold slanted him a glance, and Peregrine stammered. ‘I—I mean … It’s only that you’ve got that big sword and, well, you’re a de Burgh. Who could mistake you?’

Reynold snorted. ‘I was unremarkable enough for Thebald and Rowland to think they could master, if those were their names.’

‘Was it true, what you told him?’ Peregrine asked. At Reynold’s sharp look, he stammered again. ‘I—I just wondered because you can’t tell, by looking at you, I mean.’

‘Yes, I have a bad leg,’ Reynold said.

‘Were you injured in battle?’

Reynold shook his head. ‘I’ve had it since birth,’ he said with a carelessness he didn’t feel. But the pose came easily to him, for he was accustomed to hiding his feelings, whether it be his resentment when his brothers urged him on, making light of his affliction, his jealousy at the abilities they took for granted, or his bitterness at his place as the runt of the litter that was the grand de Burgh family.

‘Was it the midwife’s doing?’

Lost in his own thoughts, Reynold was surprised to hear the question, for no one ever asked him about his leg. He never discussed the subject. Although he could hardly reprimand the boy for simple curiosity, Reynold could not bring himself to comment, especially when the question was one none could answer. He gave a tense shrug.

‘I—I only asked because my sister helped the midwife at home, and she says sometimes the baby isn’t in the right position to come out properly. The women try to move it as best they can, but who knows what injury they might do? And some come out not at all or feet first. Is that what happened to you?’

Again Reynold shrugged. There was no use speculating since everyone involved was dead.

‘Or it could have been the swaddling,’ Peregrine said, as though thinking aloud. ‘They’re supposed to stretch and straighten the baby’s limbs, but carefully. The midwife told my sister that bad swaddling has caused men to grow up to be—’

The boy must have realised what he was saying, for he stopped abruptly, leaving his final word unspoken.

It hung in the air between them, an appellation that Reynold rarely heard, but was painful none the less. He drew in a deep breath and spoke in a tone intended to put an end to the conversation.

‘I am not a cripple.’

Chapter Two

They kept along the same road. Wide enough for a cart, it was probably designed for market traffic. After their experience the night before, Peregrine suggested a smaller track, which led to a manor house where they could rest in safety and comfort. But Reynold was not eager to proclaim his whereabouts, and he reminded the youth that danger was part of travel.

Frowning, Peregrine didn’t appear quite as eager for adventure as he had a day earlier, but ‘twas a good lesson for him, Reynold knew. Better that he learn now rather than later when they were even further into the wilds.

‘Are we going to Walsingham or Bury St Edmunds?’ Peregrine asked.

Reynold slanted the boy a glance, for he had given a pilgrimage no thought beyond using it as an excuse to leave his home. But now he considered the idea more carefully. They could hardly continue wandering aimlessly through the land, and a pilgrimage would give them a destination and a worthy one. Indeed, had he been alone, Reynold might have headed to the healing well that the thieves had mentioned—just for curiosity’s sake.

But Peregrine’s presence stopped him.

Reynold had learned to keep his private yearnings to himself long ago—when his father had caught his brother trying to sell him the tooth of Gilbert of Sempringham, the patron saint of cripples. There was nothing personal in the deceit; Stephen had quite a busy trade in dubious relics going among his brothers and other gullible parties. But, Campion, horrified by Reynold’s duping, had put an end to it.

And, Reynold, young as he had been, understood it was better to hide his feelings, along with any trace of vulnerability. His family preferred to ignore his bad leg, and so he did his best to oblige them. By now, he was so well practised in the art that he would not let anyone see himself, not even a strange lad who already knew far too much about him. So where else would they head?

‘What made you think we are going to Walsingham or Bury St Edmunds?’ Reynold asked.

‘We are heading east, my lord.’

Reynold was impressed. ‘And how can you tell that, by the sun?’

‘I’ve got a chilinder, my lord.’

Reynold looked at the lad in surprise. Not many travellers possessed the small sundial. Just how well had the l’Estranges supplied the would-be squire?

‘I looked at all the maps, too. Glastonbury is south, and Durham is north.’

Reynold began to wonder how long the l’Estranges had suspected he was leaving. He was tempted to ask Peregrine, but thought better of it. Did he really want to know the answer?

‘You obviously have your heart set on a longer journey than our thief Thebald had in mind,’ Reynold said. ‘But maps are usually of little use.’

Geoffrey, the most learned of the de Burghs, had complained that most were vague and ill made. In fact, on the map of the world, the Holy Land was at the centre, with various places of the ancient world boldly marked, while other countries were depicted only by fantastic beasts. England was at the edge of the world, as though marking the end of it, when sailors knew that was not true.

What Peregrine referred to was probably one of the routes written down that showed little or no drawings, but placed the larger towns on a line of travel and estimated the distances between them. ‘Twas a little better, but still … ‘I’d put my faith in a good reckoning by the sky, the tolling of the church bells to guide me or your chilinder,’ Reynold said.

Peregrine grinned at that, and Reynold felt his own lips curve in response. ‘Where would you like to go?’ he asked, surprising both himself and the boy. He expected that the youth would say London, for who would not want to see that great city?

Instead, Peregrine shrugged. ‘It doesn’t really matter, does it, my lord?’

Reynold slanted him a sharp glance. Had last night’s misadventure stolen all of the boy’s enthusiasm?

But Peregrine did not appear to be unhappy. ‘I just mean that where we head is not quite as important as what happens, is it?’ he said. ‘Since we are on a quest, I mean.’

Reynold snorted. Surely the boy was not hanging on to that bit of nonsense? What had the l’Estranges said? That he was to slay a dragon and rescue a damsel in distress? It sounded like one of the stories about Perceval, whose mother enjoined him to be ready to aid any damsel in distress he should encounter as a knight.

‘I hate to disappoint you, Peregrine, but I think the l’Estranges have heard too many romantic tales. I have been on many journeys and have never encountered a damsel in distress.’

‘But what of the Lady Marion?’ Peregrine asked.

Reynold frowned. Marion had been in trouble, having been waylaid upon the road, but it was his brothers Geoffrey and Simon who found her, not Reynold or Dunstan, the de Burgh who married her.

‘In fact, weren’t all the de Burgh wives once damsels in distress?’

Reynold choked back a laugh. A few of his brothers’ wives he barely considered damsels, let alone distressed ones. One or two were as fierce as their husbands, and he said as much to Peregrine. ‘If you dared suggest to Simon’s wife that he rescued her, she would have you dangling by the throat in less time than you could blink.’

‘Still, they were all in need of aid.’

‘Some, perhaps,’ Reynold said. ‘But none were menaced by a dragon. Did the l’Estranges mention to you that they enjoined me to slay one?’

That silenced the lad. When Reynold glanced his way, Peregrine was looking straight ahead, his face red. Perhaps the boy still believed in such things, and though some might have taken the opportunity to mock the youth, Reynold did not. There had been too many times when he wanted to believe himself—in the romantic tales, in the healing wells, in the possibility of making himself whole …

But he drew the line at dragons.

‘I think we’ve missed it somehow,’ Peregrine said.

The boy’s disappointed expression reminded Reynold of Nicholas, the youngest of the de Burghs, and he felt a twinge of wistful longing. Had he ever been that young and eager? He felt far older than Peregrine—and his own years.

They had been travelling for more than a week, swallowing dust, fording streams and avoiding forested areas and the brigands that frequented them. They had given away the thieves’ mount to those in need. And at Reynold’s insistence, they had kept off the old wide roads to the smaller tracks and byways, which meant they had taken a meandering route that might have led them astray.

Yet Reynold could muster no concern. While an interesting destination, Bury St Edmunds inspired no urgency, perhaps because he couldn’t help wondering what would follow their visit there. For now they were pilgrims. What would they become afterwards? Eventually, his coin would run out. And he had no wish to join the rabble of the road—outlaws, former outlaws who were sentenced to wander abroad, bondsmen who had fled their service and vagabonds who kept to unpopulated areas in order to avoid arrest.

The thought gave him pause. As a knight and a de Burgh, he was a man of discipline, ill suited to an existence without goal or purpose. He had set out to escape the happiness and expectations of his relatives, but leaving behind his family had not given him the satisfaction he had sought. Had he had hoped that once away …? But, no. He had trained himself not to hope.

‘Perhaps we should turn around,’ Peregrine suggested, rousing him from his thoughts.

Reynold shook his head. He did not like the idea of retracing their steps, making no progress, going back … ‘There’s a village ahead. We can right ourselves there.’

But when they reached the outlying buildings of the settlement, they saw no one about to question concerning their whereabouts or the direction of Bury St Edmunds. Indeed, the village was eerily devoid of life. Reynold slowed his massive mount, as did Peregrine his smaller horse, and the sound of the hooves were loud in the silence. Too loud. Around them, Reynold heard none of the typical noises—of animals, screaming babies, shouting children, bustling villagers, creaking wheels and banging tools.

The hair on the back of Reynold’s neck rose, and he tried to dismiss the notion that someone was watching them.

‘What is this place?’ Peregrine asked, his voice hushed with apprehension.

‘It looks deserted,’ Reynold said. In his travels with his brothers, he had come across the remains of abandoned buildings and even villages. ‘Sometimes the land just isn’t good enough to sustain the residents, so they move to richer soil. Sometimes repeated floods cause them to move.’ Reynold paused to clear his throat. ‘And sometimes death is responsible.’

Reynold heard Peregrine’s swift intake of breath. ‘Do you mean someone killed them?’

‘Not someone, something,’ Reynold said. ‘Sickness can strike and spread, wiping out all but a few who flee for their lives.’ His words hung in the air, and he tried not to shudder. Unlike his brothers, who carelessly considered themselves invincible, Reynold was aware of his own imperfections and mortality, and he felt a trickle of unease.

‘Then maybe we should turn around.’

‘No.’ Reynold spoke softly, but plainly. This place did not hold the stink of death, and yet it seemed that something was not right. What was it?

‘So there’s nothing to be afraid of?’ Peregrine asked. His question, hardly more than a whisper, was followed by the sudden sharp sound of something flapping in the breeze, and Reynold saw the boy flinch.

‘No,’ Reynold said, even as he wondered how long the village had stood empty. The roof thatching had not deteriorated, and the buildings were well kept. Instead of ruins and weeds, he saw homes that appeared inhabited, except there was no one. No people. No animals. No life.

‘It looks like they just left, doesn’t it?’ Peregrine asked in a shaky voice.

The situation was peculiar enough to make a grown man wary, but Reynold found no signs that the place had been attacked—by man or disease. There were no corpses to be seen—or smelled—and no evidence of recent graves. The residents were just … gone.

‘Maybe they are off to a fair or festival elsewhere or were called up to their lord’s manor,’ Peregrine said.

Reynold shook his head. He could think of no instance in which every person, able or not, man, woman or child, would be commanded to leave their homes. And the huts were neatly closed, animals and possessions gone, as far as he could tell.

‘My lord, we are headed in the wrong direction. Let us go back,’ Peregrine said, and there was no mistaking his anxiety.

Again Reynold shook his head, and this time he held up a hand to silence the lad. Had he heard faint footsteps, or was that simply the same piece of leather flapping in the breeze? Although he could perceive no threat, Reynold still felt as though eyes were upon him, taking in their every move. If so, constant chatter was a distraction, as well as providing information to the enemy.

Reynold was aware that the seemingly deserted structures could hide brigands nearly as well as a wooded area, but he had no intention of turning tail and fleeing. He had never walked away from a fight and was not about to start now, even if he and the boy were outnumbered.

But as they moved forwards, nothing stirred except the tall grasses that surrounded a pond, where the mill was quiet, its wheel still. A small manor house stood apart, further from the road, its doors and shutters closed. Ahead lay the ruins of a stone building, and then the road veered round an odd hill. Opposite a small church was situated, unremarkable except for some kind of decoration on its side. Reynold slowed his mount further in order to take a better look, only to draw in a sharp breath of recognition.

‘Is that a dragon?’ Peregrine whispered. Again, the words had barely left his mouth when a sound echoed in the silence. But this time it was no errant noise produced by the wind, but the loud and unmistakable ringing of bells. Church bells.

Sabina Sexton stood in the shadows of the chapel as the echoes died away and watched the two strangers in the roadway.

‘This will surely be the death of us!’ Ursula said, dropping the bell ropes as though they burned her.

‘Even brigands would not kill us in a church, surely,’ Sabina said, hoping it were true. She had run out of options, and these two were the first people they had seen in weeks. When young Alec had alerted her to their arrival, she had hurried to the church, hoping that a meeting here would offer more protection than the roadway.

‘And these two do not resemble robbers. Perhaps they are pilgrims,’ Sabina said.

‘Then how are they to help us? They will likely run away and spread the tale of Grim’s End even further afield.’

Sabina hoped not, for already they were cut off, their small corner of the world avoided by any who knew of its troubles. Outside, the man dismounted, and Sabina stepped to the window for a better view. ‘He does not have the look of a pilgrim, nor does his horse. That is a mighty steed, the kind a knight would ride.’

Ursula hurried over to join her, but Sabina kept her attention on the stranger. There was something about the way he held himself that made him different from any man she had ever seen. Straight and tall, wide-shouldered, with dark hair falling to his shoulders, he wasn’t dressed as a knight, and yet he had not fled the village. Nor did he seem fearful, just wary. And confident.

‘He wears no mail or helmet or gauntlets,’ Ursula said.

‘Yes, but look at his sword,’ Sabina whispered. The scabbard was too large to hold the sort of weapon a pilgrim would carry or handle with ease, unless that pilgrim were a knight …

‘He has a harsh visage,’ Ursula said, and Sabina finally turned to face her attendant.

‘He does not,’ Sabina whispered. She was about to vow that she thought him handsome, but Ursula’s worried expression stopped her. As did the realisation that she should not be focusing on such unimportant details when so much was at stake.

‘Very well. Then let me speak to them, mistress, while you hide in the cupboard,’ Ursula said.

‘Nay. You hide, and I will treat with him.’

‘Mistress, you do not understand! You are a young, beautiful woman. We know nothing of this man, except that he looks dangerous. At least wait until Urban arrives.’

‘I cannot wait,’ Sabina said heatedly, though she kept her voice to a whisper. ‘If we dally, these two will be gone, and our last chances for aid gone with them.’

Ursula started wringing her hands. ‘Mistress, please, we can leave ourselves. We have but to—’

Sabina cut her off with a sharp shake of her head. The argument was a familiar one, which she did not intend to resume here and now. Quickly, she glanced out the window to see that the boy had dismounted as well, but it was the man who held her interest. Large, muscular and formidable, he seemed the answer to her prayers. Drawing a moaning Ursula to her side, Sabina stepped back into the shadows, her hand on a small dagger that was hardly more than an eating utensil.

It would be little use against the strength of the stranger, but Sabina did not fear for her safety. Instead, despite Ursula’s warnings and the man’s grim expression, for the first time in months she felt a glimmer of hope.

Motioning the pale-faced Peregrine towards the door of the building, Reynold drew his sword. He had never stepped so armed into a place of worship, but this was no ordinary church. Those bells had not rung themselves, and he did not wish to be cut down by robbers intent upon luring their victims inside. At his nod, Peregrine pulled open the door, and Reynold peered into the darkness. But he saw no movement within.

‘Maybe the wind struck the bells,’ Peregrine whispered.

Holding up a hand for silence, Reynold slipped into the building, but the shadowed interior appeared empty, and he heard nothing except what sounded suspiciously like a whimper from Peregrine.

‘Who is there? Show yourself.’

‘Don’t kill us! Have mercy!’ a female voice rang out, and an older woman fell before him, quaking with fear.

Reynold stepped back, startled, for she was no beggar, dressed in rags. Nor did she appear to be ill or hurt, a victim abandoned by her fellows. But she could be in league with robbers, who, as he had already discovered, went to great lengths for any spoils.

‘Who else is here?’ Reynold called, refusing to let down his guard.

‘Only I.’ It was a woman’s voice, but unlike the shrill screech of the other’s, this one was low and smooth and made Reynold think of honey. The figure that emerged from the shadows was different, too. Definitely not a cutpurse or any sort of mean female, she was dressed in the finer clothes of a lady and held herself thusly, with grace and composure.

And she was beautiful, like an image from a book or a tapestry. Golden hair fell about her shoulders, and her skin was flawless and pale. Although she was slender, her dark green gown revealed a woman’s form, and Reynold had never seen any who so approached the romantic ideal. For a long moment he simply stared, wondering whether she was some sort of vision. But Peregrine’s gasp told Reynold that he had seen her, too.

‘I am Sabina Sexton of Sexton Hall here in Grim’s End, and this is Ursula,’ she said, helping the older woman, who was still shaking, to her feet.

‘Grim’s End?’ Peregrine’s voice was little more than a squeak.

‘Yes. May I not know your name?’

‘Peregrine,’ he answered. Then he stepped into the light, so as to make a better target of himself. But before Reynold could reprimand him, he spoke again. ‘And this is Lord Reynold de Burgh.’

Reynold frowned. Had the boy not learned to keep his confidences? If they were outnumbered, they might well be held for ransom and Reynold would wring the cost out of his squire’s hide. But a few strides around the inside of the church revealed no one else. Yet why would these two be here, alone in a deserted village? Had they survived some illness that had killed the other inhabitants?

‘We are pilgrims, on our way to Bury St Edmunds,’ Peregrine said, and Reynold shot him a quelling look. But the boy appeared to be totally enthralled by the woman, and who could blame him? Fleetingly, Reynold wondered whether she was some kind of siren, luring travellers to their death in this empty place called, fittingly, Grim’s End.