Полная версия

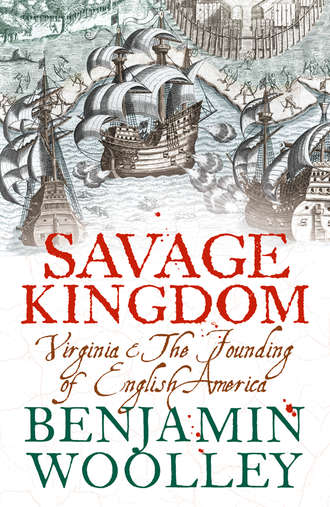

Savage Kingdom: Virginia and The Founding of English America

SIX Soundings

THE FRAGILE FLEET of three wooden ‘eggshells’ sailed past a cape on the southerly lip of the Chesapeake Bay, and dropped anchor on the south shore. To the north, a vast body of water stretched to the horizon. To the west, low-lying land receded as far as the eye could see. The English had found Virginia.1

‘There we landed and discovered a little way,’ wrote Percy, who was a member of the first thirty-strong landing party to go ashore that warm spring day in late April 1607. ‘But we could find nothing worth the speaking of but fair meadows and goodly tall trees, with such fresh waters running through the woods as I was almost ravished at the first sight thereof.’

They stayed all afternoon, using the remains of a long day to take in their new surroundings. As darkness fell, they made their way back to the beach. Then, ‘there came the savages creeping upon all fours from the hills like bears, with their bows in their mouths, [who] charged us very desperately’. The English let off volleys of musket fire, which to their surprise the Indians ‘little respected’, not withdrawing until they had used up all their arrows. Gabriel Archer was injured in both his hands, and Matthew Morton, a sailor, was shot ‘in two places of the body very dangerous’. The casualties were carried back on to the boats, and the English withdrew to their ships.2

Later that evening, there was a solemn gathering of all the leading members of the expedition aboard the Susan Constant. According to their orders from the Royal Council, within twenty-four hours of their arrival at Virginia, they were to ‘open and unseal’ the secret list nominating the settlement’s ruling council, ‘and Declare and publish unto all the Company the names therein Set down’.3

Newport announced the names chosen by the Royal Council in England. His own was listed first, followed by Wingfield’s and Gosnold’s. Another nomination was John Martin, the sickly son of Sir Richard, a prominent goldsmith and the Master of the Mint. Martin’s election was probably a foregone conclusion, given the wealth of his family and their generosity as patrons of this and other ventures.4

More surprising was the appearance of the mysterious George Kendall and John Ratcliffe on the list, together with Captain John Smith. The latter’s inclusion might have suggested his immediate release from the brig, but Newport decided to keep him there for the time being.

George Percy and Gabriel Archer were not nominated. Percy may have been excluded because of worries about the loyalty of his brother, the Earl of Northumberland. The reasons for excluding Archer, who had worked so hard with Gosnold to promote the venture in its early years, were more opaque, and he took the news badly.

The council’s first job was to nominate a president, who would supervise the taking of the oath of office. But rumbles of recrimination, puzzlement about the roles of Ratcliffe and Kendall, and the difficulty of deciding what to do about Smith discouraged such finalities.

The following day the mariners brought up from the hold the expedition’s collapsible three-ton barge or ‘shallop’, and started to assemble it. Meanwhile, a landing party continued reconnoitring the surrounding territory. Several miles inland, they spotted smoke. They walked towards it, and came upon a campfire, still alight with oysters roasting on a barbeque. There was no sign of the picnickers, so the English polished off the meal, observing as they licked their fingers that the oysters were ‘very large and delicate in taste’.5

The next day, 28 April, the shallop was launched, and Newport, together with a group selected from the ranks of the ‘gentlemen’, set off in search of a river or harbour suitable for settlement. The only map they had was one based on explorations made during the Roanoke expedition of 1585. This showed the south shore of the bay as interrupted by a series of inlets, one leading to the village of Chesapeake, the other to ‘Skicoac’. The shoreline ended at what appeared to be the mouth of a river, which flowed west. The river’s northern bank was a peninsula, which was marked with a dot, indicating an Indian settlement. To the north of the peninsula was another river, flowing north-west. Along the top of the map was what appeared to be the northern shore of the bay, populated by two villages, ‘Mashawatec’ and ‘Combec’.

What they might have imagined to be the inlet leading to Skicoac proved to be nothing but shoal water, barely suitable for their shallop, let alone a ship. As they coasted deeper into the bay, they apparently passed the first river mouth, and came to the peninsula. They disembarked on one of the beaches, and explored its perimeter. They found a huge canoe, 45 foot long, made from the hollowed-out trunk of a large tree. They also found beds of mussels and oysters ‘which lay on the ground as thick as stones’, some containing rough pearls.6

Exploring inland, they found the land became more fertile, ‘full of flowers of divers kinds and colours,’ remarked Percy, ‘and as goodly trees as I have seen, as cedar, cypress, and other kinds’. They also found a plot of ground ‘full of fine and beautiful strawberries four times bigger and better than ours in England’. Great columns of smoke could be seen rising from the interior, and they wondered anxiously whether the Indians were using fires to clear land for planting, or ‘to give signs to bring their forces together, and so to give us battle’.

Returning to the shallop, they sounded the surrounding waterways, but could find none deep enough for shipping. They returned both buoyed up and dragged down by the day’s discoveries. The land was so inviting, but worthless to them if they could not find a suitable river or safe harbour.

Later that evening, a group rowed out to examine further the river mouth they had passed earlier that day. They started to zigzag across the water, taking soundings as they went. Slowly, painstakingly, their measurements built up a profile of the river bed beneath, revealing a channel 6 to 12 fathoms deep, enough for heavy shipping. So great was their relief, that Archer named the neighbouring point of land ‘Cape Comfort’.

With this discovery, the decision was taken to commit the settlement’s fortunes to the Chesapeake. To mark the decision, a group rowed to the southern side of the mouth of the bay, and on the promontory they had passed when they arrived erected a large cross, facing out to the ocean. They named the land upon which they stood Cape Henry, in honour of Tyndall’s patron, James’s 13-year-old heir.

On 30 April 1607, the fleet nosed past Cape (later known as Point) Comfort and into the broad river that lay beyond. Five Indians appeared on the shore, running along the beach to keep up with the ships. Newport called to them from the deck of the Susan Constant. At first they did not respond. Newport then laid his hand upon his heart as a gesture of friendship. They laid down their bows and arrows, and waved to him to follow them. Newport, together with Percy and a few others, clambered into a boat, and rowed towards the shore. The Indians dived into a tributary and swam across with their bows and arrows in their mouths. The English followed, until they found themselves floating towards a group of warriors waiting for them on the bank. From there, they were escorted to a town, which the English understood to be called ‘Kecoughtan’.

Kecoughtan comprised a cluster of twenty or so dwellings built ‘like garden arbours’, interspersed among the trees. The walls of each house were made of saplings, the roof by the branches bent over to create a vault. The entire construction was covered with reed mats and in some cases with bark, a free-hanging mat acting as the door. The English were intrigued by the elegant simplicity of the buildings, and the lack of permanent structures or even of locked doors.7

The Indians who emerged from the houses presented a sight not altogether unfamiliar to some of the English, as they wore clothes and followed customs similar to those at Roanoke, whose appearance had been carefully recorded by the painter John White. The most distinctive feature was the hair. The men shaved the right side of their heads, and let the left side grow to the length of an ‘ell’ (3 foot 9 inches), which they tied in an ‘artificial knot’ and decorated with feathers. In the intensifying heat of the Virginian late spring, they dressed sparingly, covering their ‘privities’ with an animal hide decorated with teeth and small bones, but were otherwise naked. To welcome the English, some had painted their bodies black, others red, ‘very beautiful and pleasing to the eye’, and wore turkey claws as earrings.8 Gabriel Archer, standing among the exhausted, louse-ridden, poorly-nourished English could only admire the strength and agility of the ‘lusty, straight men’ whom they now encountered.9

As soon as the English entered the village, the men greeted them with a ‘doleful noise’, and approached ‘laying their faces to the ground, scratching the earth with their nails.’ Percy, a man of insecure religious convictions, was alarmed, fearing that the Indians were practising their ‘idolatry’ upon him.

Once the welcome was over, the Indians brought mats from their houses and lay them on the ground. The elders sat in a line, and were served with corn bread, which they invited the English to share, but only if they sat down. The English crouched awkwardly on the mats ‘right against them’, and accepted the offer. The elders then produced a large clay pipe, with a bowl made of copper, and filled it with tobacco. It was lit, and they offered it to their guests, who puffed it appreciatively.

To complete the ceremonies, the Indians put on a frantic dance, ‘shouting, howling, and stamping against the ground, with many antic tricks and faces, making noise like so many wolves or devils’. The display lasted half an hour, during which Percy, drawing on a knowledge of courtly dance acquired as a child, noticed that they all kept to a common tempo with their feet, but moved to an individual rhythm with the rest of their bodies.

When the dance ended, Newport presented the elders with beads and ‘other trifling jewels’. The English then returned to the fleet, content that, as instructed by the Royal Council, they had not only taken ‘Great Care not to Offend the naturals’, but laid the basis of a fruitful trading relationship.

Over the following few days the fleet carefully felt its way up the broad river, which even 20 or so miles upstream was wider than any in England, the channel deep enough for large ships. Tyndall carefully mapped the route of the channel, naming a large and treacherous sandbank about 30 miles upstream ‘Tyndall’s Shoals’. Just beyond, the river turned sharply, forming a loop similar to that of the Thames around the Isle of Dogs, which was later named the ‘Isle of Hogs’ (now home to a wildlife reserve, and a nuclear power plant). Opposite it, Gabriel Archer spotted an island which looked ideal as a location for their settlement. He had a fondness for puns, so he dubbed it ‘Archer’s Hope’, a ‘hope’ also being a stretch of land cut off from its surroundings by marsh or fenland.

Continuing slowly upstream a further 20 miles, they reached a point where the river forked. They anchored the fleet in the broad waters of the confluence, and a landing party was sent to reconnoitre. They came to a town called Paspahegh, on the northern shore of the wider tributary, where they were entertained by an ‘old savage’ who made ‘a long oration, making a foul noise, uttering his speech with a vehement action, but we knew little what they meant’. While witnessing this unimpressive spectacle, they were approached by the chief or weroance of the tribe on the southern bank of the river, who had paddled over in a canoe to remonstrate with them for favouring the Paspahegh over his own people. Gratified by this competition for their attention, and dismissive of the Paspahegh’s efforts, the English said they would visit him the next day.

The following dawn was heralded by the arrival of a canoe alongside the Susan Constant, paddled by a messenger, who signified that he had come from the chiefdom on the opposite bank of the river. He beckoned the English to follow him. They duly manned their shallop, and pursued the canoe to the southern shore, which some had begun to call the ‘Salisbury Side’, in honour of Cecil, the Earl of Salisbury. As the English drew up by the river bank, Percy beheld the chief and his warrior escort waiting for them, ‘as goodly men as any I have seen of savages or Christians’.

The chief, called Chaopock, presented a particularly impressive spectacle, his body and visage a map of promising commodities. His torso was painted crimson, which was perhaps how he got his name, the local word chapacor being the name of a root used to produce red dye. His face was painted blue, ‘besprinkled with silver ore as we thought’, probably a paste made of antimony, which was mined further north. He wore ‘a crown of deer’s hair coloured red in fashion of a rose fastened about his knot of hair’, and on the shaven side of his head, a ‘great plate of copper’. He played a reed flute as the English clambered ashore, and then invited them to sit down with him upon a mat, which was spread out for them on the bank. There, sitting ‘with a great majesty’, he offered them tobacco, his company standing around him as they watched the English puff on the pipe. He then invited them to come to his town, which the English understood to be called Rappahannock (but which they later learned was called Quiyoughcohannock). He led them ‘through the woods in fine paths, having most pleasant springs’, past ‘the goodliest cornfields that ever was seen in any country’, up a steep hill to his ‘palace’, where they were entertained ‘in good humanity’.10

The next day, Newport left the fleet riding at anchor before Paspahegh and continued in the shallop up the wider branch of the river, stopping at a point where it once again divided. There he encountered another tribe, the ‘most warlike’ Appamattuck, who came to the banks of the river and confronted the English, their leader crouched before them ‘cross-legged, with his arrow ready in his bow in one hand and taking a pipe of tobacco in the other’ uttering a ‘bold speech’. After an exchange of peaceful gestures, the English were allowed ashore, giving them an opportunity to admire the swords the Appamattuck carried on their backs, a unique weapon with a blade of wood edged with sharp stones and pieces of iron, sharp enough ‘to cleave a man in sunder’.

Having established that there was no suitable location for the settlement upstream, the shallop returned to the fleet. On 12 May, Wingfield and other members of the council took the pinnace back downriver to Archer’s Hope, to assess its viability as the best site for their settlement. A landing party found that ‘the soil was good and fruitful with excellent good timber’. They found vines as thick as a man’s thigh running up to the tops of the trees, turkey nests full of eggs, hares and squirrels in the undergrowth, birds of every hue – crimson, pale blue, yellow, green and mulberry purple – fluttering through the forest canopy. Returning to the ship, the council assembled to consider whether this should be the site for their settlement. Gosnold and Archer, perhaps with Percy’s support, argued strongly for its merits: the abundance of natural resources around, its defensible location, ‘which was sufficient with a little labour to defend ourselves against any enemy’. But Wingfield was worried about the sandbanks, which prevented shipping coming close enough to the shoreline to allow cargo and people to transfer directly on to land, a handicap that many considered the reason the Roanoke settlement had proved unsustainable. The other worry was the position of the Kecoughtans. Hakluyt had advised that the settlers should ‘in no case suffer any of the natural people of the Country to inhabit between you and the sea’.

After a heated debate, they sailed around the Isle of Hogs to look at an alternative site. It had been brought to the settlers’ attention by the Paspahegh, who claimed it to be part of their territory. It was a promontory sticking into the river, creating a constriction that forced the deep-water channel right up to the shore. In a daring test of its suitability, one of the ships was sailed up to the river bank, close enough to be tethered to the trees.

The settlers disembarked and investigated the area. They were standing on a peninsula which dangled like a piece of fruit from the mainland, its stalk a thin causeway across an otherwise impassable swamp. They also noted that the shoreline used to moor the pinnace was shielded by woods from enemy vessels coming upstream. It had once been inhabited by Indians, and some evidence may have survived of their presence, but they were long gone.

The site presented difficulties. The river and surrounding creeks and streams were brackish, so a well would have to be dug, or fresh water supplies brought in by ship. The site was also covered with large trees and thick vines which would take considerable effort to clear. There was also the issue of the Kecoughtans controlling land access to the bay.

After further arguments, during which Gosnold repeated some of his objections, the fateful decision was taken to make this the site of their settlement. As tools and supplies were unloaded from the ships, the council now gathered to constitute itself. More arguments erupted over whether Smith and even Archer should be co-opted, but in the end it was decided they should be excluded. Each council member then took the oath of allegiance, and elected Wingfield their president.

‘Now falleth every man to work,’ as Smith later put it, labourers to clearing the ‘thick grove of trees’ covering the western end of the site, soldiers to scouting the mainland, farmworkers to tilling soil and planting seeds, and President Wingfield to tending the breeding flock of thirty-seven chickens he had brought from London.

Conditions were tough. Most of the settlers slept under trees. Those who could afford to bring one enjoyed the comforts of a tent. The elderly Wingfield benefited from this and other indulgences, including the ‘divers fruit, conserves, and preserves’ he had packed into his trunk, though he later claimed that some had been pilfered.11

For spiritual sustenance, the settlers erected a makeshift chapel out of an ‘awning (which is an old sail)’ hung between the trunks of ‘three or four trees to shadow us from the Sun’. ‘Our walls were rails of wood, our seats unhewed trees, till we cut planks, our Pulpit a bar of wood nailed to two neighbouring trees,’ Smith recalled, and ‘in foul weather we shifted into an old rotten tent, for we had few better.’12 In honour of their King, the council dutifully called this ramshackle collection of tents pitched on a sweaty island in the middle of a teeming forest ‘Jamestown’.

The activity on the island attracted the attention of the Paspahegh people, who visited the site on several occasions to see what was going on. To prevent causing offence, Wingfield banned the building of any permanent defensive structures and the performance of military exercises. This was in line with Hakluyt’s instructions, which urged the settlers to develop trading relations with the Indians ‘before they perceive you mean to plant among them’. Smith, however, had different ideas.

It is unclear whether Smith had yet been released from his shackles, but he was still excluded from the council’s deliberations, and he railed at Wingfield’s decision, claiming it was motivated by ‘jealousy’, his possessiveness of power. According to the Charter, the King had accepted the patentees’ request to settle Virginia principally so that they ‘may in time bring the infidels and savages living in those parts to humane civility and to a settled and quiet government’. This for Smith was royal absolution for a great civilizing mission, which should begin as it was supposed to proceed.13

For the time being, Wingfield’s low-key policy prevailed, though Kendall, who it now transpired had some experience of military engineering in the Low Countries, managed to erect one bulwark, ingeniously constructed out of ‘the boughs of trees cast together’, possibly towards the isthmus joining the island to the mainland.

On 18 May, the Paspahegh chief himself paid a regal visit to the island with a hundred of his warriors, who ‘guarded him in a very warlike manner with bows and arrows’. The chief asked the English to lay down their arms, which they refused to do. ‘He, seeing he could not have convenient time to work his will, at length made signs that he would give us as much land as we would desire to take,’ Percy claimed. Whether or not it had been properly understood, the chief’s gesture relieved the tension, and the English put away their weapons. Then a fracas erupted between one of the English soldiers and an Indian, apparently over a stolen hatchet. One struck the other, and soon bystanders were joining in, provoking the nervous English to ‘take to our arms’. In response, the chief left ‘in great anger’, followed by his retinue.

Two days later, forty of the Paspahegh arrived with a deer carcass, apparently a peace offering. At the invitation of one of the English soldiers, they also put on an impressive demonstration of their shooting skills. The soldier propped a ‘target’ or shield ‘which he trusted in’ up against a tree, and gestured to the Indian to take a shot at it with his bow and arrow. To the soldiers’ astonishment, the arrow penetrated the shield ‘a foot through or better, which was strange, being that a pistol could not pierce it’.

By this stage, life for the settlers was settling into a routine, and some were beginning to feel a little at home. A group surveying the surrounding land found ‘the ground all flowing over with fair flowers of sundry colours and kinds as though it had been in any garden or orchard in England’.14

Many of the settlers were by now anxious that Newport should head back home at the earliest opportunity to fetch more supplies. The mission plan had been drawn up on the basis of a return by May of that year 1607, and provisioned accordingly. But on Thursday 21 May, Newport declared that, rather than embark for England, he would lead the ‘discovery’ of the river commissioned by the Royal Council. From his perspective, his own future, as well as that of the mission, rested upon the discovery of precious metals, or navigating a new route to the South Seas. He could not afford to go home empty-handed.

He chose to accompany him George Percy, Robert Tyndall, Gabriel Archer – who was to keep a journal – and Thomas Wotton, the surgeon. He also decided to release Smith from custody and take him too, perhaps to keep him out of Wingfield’s way, or to offer him an opportunity to redeem himself. The rest of the company was made up mostly of the crew of his ship, the Susan Constant. The Royal Council had also called for Gosnold to ‘cross over the lands’ with twenty men, ‘carrying half a dozen pickaxes to try if they can find any mineral’. No such expedition was mounted.

As the time approached for Newport’s departure, he called his men before him, and pledged that none would return until they had found ‘the head of this river, the lake mentioned by others heretofore, the sea again, the mountains Apalatsi, or some issue’, by which he meant the legendary saltwater lake somewhere in the American interior, which might provide navigable access to the ‘South Sea’ or Pacific, and the Appalachian mountain range, from which was said to run the ‘stream of gold or copper’.15

At noon, they climbed aboard the shallop, hoisted its sails, and, beneath a hot, early summer sun, began their slow progress upstream.

By the first night they had managed 18 miles, reaching a ‘low meadow point’ on the south side of the river. There they met the Weyanock people, who claimed to be hostile towards the Paspahegh. The following morning, they set off early, managing 16 miles before breakfast. Stopping at an islet created by a large loop in the river, they found ‘many turkeys and great store of young birds like blackbirds, whereof we took divers which we break our fast withal’.