Полная версия

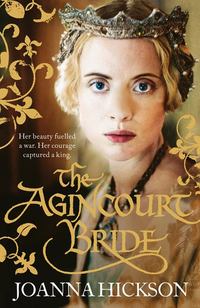

The Agincourt Bride

The children liked the new clothes and the better food and didn’t associate them with the terrifying encounter in the governess’ chamber. They hardly noticed that there was now a double guard on the nursery tower and that armed soldiers shadowed us whenever we ventured out for fresh air, but I certainly noticed these things, for I became a virtual prisoner, unable to visit Jean-Michel or my parents. Consequently, it was some time before I discovered what had been going on in the outside world.

Had I known that the three older royal children had never reached Chartres, but had been abducted from their mother’s procession and forced into Burgundian marriages, I might have been more prepared for what was to come. In the event, perhaps ignorance was bliss, because when she asked about her sister and brothers I wasn’t able to tell Catherine that Louis had been forced into a binding betrothal with Burgundy’s daughter Marguerite and had since been confined in the Louvre with Burgundian tutors, while his sister and brother had been whisked away to live with the children to whom Burgundy had matched them; Michele in Artois with the duke’s only son Philippe, and Jean in Hainault with Burgundy’s niece, Jacqueline, his sister’s daughter. However, I also heard that, far from considering themselves beaten, the queen and the Duke of Orleans had raised an army to confront Burgundy outside Paris. The king remained mad and confined, and the spectre of civil war stalked the land.

For the next three weeks I lived on tenterhooks, happy to have sole charge of Catherine and her little brother, but daily expecting a new governess to arrive and take over in the nursery. One September morning I believed that moment had arrived.

Little Charles had never been much of an eater. Who could blame him, given the awful slops he had been offered during most of his short life? I was encouraging him to finish his breakfast bowl of fresh curds sweetened with honey – a new and delectable treat – when there was a commotion on the tower stair. The door of the day nursery flew open to admit a richly dressed lady shadowed by a large female servant in apron and coif, not unlike my own. I sprang to my feet and hovered protectively over the children, who looked up in fright.

‘I am Marie, Duchess of Bourbon,’ the newcomer announced, without smile or greeting and only the merest glance to show that her words were addressed to me.

I backed away and dropped to my knees, my apprehension rising rapidly as she continued speaking. ‘His grace of Burgundy has requested me to make arrangements for the care of the king’s children.’

The mention of Burgundy rang loud alarm bells in my head. ‘Y-yes, Madame,’ I stuttered.

Catherine heard the name Burgundy and the tremor in my voice and her gaze swivelled in panic from me to the grand visitor. ‘No!’ she cried, instinctively sensing danger. ‘No, Mette. Make them go away.’

Marie of Bourbon glided forward and knelt by Catherine’s stool. With a smile and a touch she tried to reassure the trembling child. ‘Do not be frightened, my little one,’ she cooed. ‘There is nothing to fear. Your name is Catherine, is it not? Well, Catherine, you are a very lucky girl. You are going to a beautiful abbey where kind nuns will look after you and you will be safe. You will like that, will you not?’

Catherine was not fooled by a soft voice and a tender touch. ‘No! No, I want to stay with Mette.’ Like a whirlwind, she jumped off her stool and ran to my side, closely followed by little Charles, curds dribbling down his chin.

Still on my knees, I put my arms around them, tears springing to my eyes. ‘I am sorry, Madame,’ I gulped, avoiding the lady’s gaze. ‘There has been much upheaval in their lives lately and I am all they know.’

Marie of Bourbon rose and her tone became brisk as her patience grew thin. ‘That may be, but these are no ordinary children. They have been woefully neglected and it is time they were given the training they need and deserve. I will be taking Charles with me now. He is my father’s godson and he is to live in his household and receive the proper education for a prince. You are to prepare Catherine for her journey to Poissy Abbey. She will be leaving tomorrow morning.’ She waved an imperious hand at her servant. ‘Get the boy. We are leaving.’

Before he realised what was happening, Charles was swept up in a pair of sturdy arms. He set up a shrill screech and began to kick and struggle, but the woman had been picked for her strength and his puny efforts were stolidly ignored.

‘No! Put him down!’ Catherine screamed and ran at the woman, swinging on her arm and trying unsuccessfully to dislodge her brother. With tears of fear and frustration, the little girl turned to me. ‘Mette, don’t let them take him! Help him!’

Miserably, I shook my head and wrung my hands. What could I do? Who was I against the might of Burgundy, Bourbon and Berry? Our last sight of Charles was of his agonised, curd-spattered face and his outstretched hands as his captor descended the stairs but the sound of his screams persisted, punctuated by Catherine’s sobs. Marie of Bourbon’s cheeks were flushed and her expression grim as she stood in the doorway and gave me final instructions, raising her voice above the commotion.

‘I will come for Catherine at the same time tomorrow. See that she is prepared to leave. I do not want any more scenes like this. They are vulgar and unpleasant and not good for the children.’

‘Yes, Madame.’

I had bowed my head dutifully, but my deference disguised a mind whirling with wild rebellious notions. Could I whisk Catherine off to the bake house and raise her as my own child? Could I flee with her to some remote village? Could I take her to the queen? But even as these ideas flashed through my mind, I knew that no such course of action was feasible. Catherine was the king’s daughter, a crown asset. Stealing her would be treason. We would be hunted down and I would be put to death and how would that help her, or my own family? To say nothing of myself! As for taking her to the queen – I did not even know where she was, let alone how to get there.

I suppose I should have been grateful that we had another day together, that Catherine had not also been carried instantly to a closed litter, while Burgundy’s guards turned deaf ears to her heart-rending screams. At least I had a few hours to prepare her for our separation and to try and convince her that it was for the best.

How do you persuade a little girl of not quite four that what is about to happen is not the worst thing in the world when, like her, you completely believe that it is? How was I to make my voice say things that my heart utterly denied? I had heard cows bellowing in the fields when their calves were taken from them and I could feel a thunderous bellow welling up inside me; one that, if I let it out, would surely be heard throughout the whole kingdom. But I knew that I could not – must not – if I was to help Catherine face up to her inevitable future.

At first she wept and put her hands over her ears, screwing up her eyes as she cried, ‘No, Mette, no. I won’t leave you. They c-cannot make me. I will stay here and you can f-fetch Charles back and we will be happy, like we were b-before.’

I held her tightly in my arms. She was shaking and hiccupping. Wretched though I felt, I had to deny her. ‘No, Catherine. You must understand that you cannot stay here and that you and I cannot be together any more. You have to go and learn how to be a princess.’

She broke away from me and started shouting indignantly, ‘But why? You are my nurse. You have always looked after me. I thought you loved me, Mette.’

Ah, dear God, it was soul-destroying! Loved her? I more than loved her. She was an essential part of my being. Losing her would be like losing my hands or tearing out my heart, but I had to tell her that although I loved her, I had to let her go. She was not my daughter but the king’s and she had to do what her father wished.

‘But the king is mad,’ she cried. ‘We saw him in the garden. He does not care about me. He does not even know who I am.’

Out of the mouths of babes …! It was heartbreakingly true. He and his queen may have loved Dauphin Charles, the golden boy who had died, but none of the rest of their surviving offspring could be said to have benefited from one morsel of parental concern.

‘But God cares,’ I responded, grasping at straws. ‘God loves you and you will be going to His special house where His nuns will look after you and keep you safe.’

‘Does He love me as much as you do?’ Her breath was shuddery and in her little flushed face her eyes were round and questioning. My darling little Catherine. Those enchanting, deep sapphire eyes seemed to hold the entire meaning of my life, even reddened and swollen as they were. The image of them would stay with me for ever.

‘Oh yes,’ I lied. Call it blasphemy if you like, but I swear that the Almighty could not have loved that little girl as much as I did. ‘He loves us all and you must remember His commandment – the one about honouring your father and your mother, which means you must do as they say.’

‘But that lady said it was the Duke of Burgundy who sent her. He is not my father. I hate him. I do not have to do as he says, do I?’

Sometimes, I thought, she was far too bright for her own good.

Involuntarily, I touched my cheek, which would always bear the mark of Burgundy’s vicious, studded gauntlet and swallowed hard on the bile his name inspired. ‘Well, yes, Catherine you do, because he is your father’s cousin and helps him to rule his kingdom.’

I could sense her desperate resistance crumbling. Her shoulders drooped and her lower lip began to tremble. ‘What about my mother? Does she want me to go away to this place?’

Who knew what the queen wanted? I had heard that she and Orleans had raised an army, but so far no other news of her had reached my ears.

‘I am sure the queen agrees with the king,’ I answered lamely, casting about in my mind for some way of distracting her. ‘Now, supposing we go out for a bit? Shall we go and light a candle to the Virgin and ask her to protect and keep us until we meet again?’ I hoped the guards would not stop us going to the chapel and that its peaceful atmosphere might calm us both. I might pray for a miracle, I thought, but in my heart I knew that not even the Blessed Marie would be able to save us from Marie of Bourbon.

I was so proud of my darling girl when she took her leave the next morning. She and I had already said our farewells, exchanging a long embrace and many tearful kisses before I laced her into her new, high-waisted blue gown, ready for the journey. Then I brushed out her long, fine, flaxen hair for the last time and tied the ribbons of a white linen cap under her chin, trying not to let my hands shake and transmit my own churning emotions to her. When the Duchess of Bourbon held out her hand to lead Catherine to the waiting litter, she looked the perfect royal princess; obedient, sweet and decorous. Only two bright pink patches on her cheeks indicated the misery and turmoil beneath the calm façade. Looking back, I think the diamond quality of her character was revealed in that moment.

At the door of the litter the grand lady turned to me with a gracious smile. ‘I believe your name is Guillaumette,’ she said. ‘For one who can have no knowledge of courtly manners, you have done well by the princess. However, I am sure you understand that there is much for her to learn that you could never teach her. Now you may go to the grand master’s chamber and collect what is due to you. The nursery is to be closed. Goodbye.’

As the litter swung out of sight through an archway, I longed to run after it and shout, ‘I do not want what is due to me! I do not want your blood money! No payment can be recompense for losing my darling girl!’

But I did not. I stood, frozen like a statue, praying. I prayed that Catherine knew my love for her was unconditional, knew that it would never fade and that whenever – if ever – fate brought us together again, she would remember her old nurse Mette. I was nineteen years old and I felt like a crone of ninety.

PART TWO

Hôtel de St Pol, Paris

The Shades of Agincourt

1415–18

6

‘I have news that may lift your spirits,’ said Jean-Michel as we lay in bed, whispering so as not to wake our children who slept in the opposite corner of the cramped chamber.

‘News of what?’ I responded dully, too tired to rouse much interest. I was always tired these days – had been ever since returning to the Hôtel de St Pol, after years away. Many highs and lows had led to Jean-Michel and I sharing a bed together in the royal palace and our lives were very different now.

For over eight years I had raised my children in my old home under the Grand Pont. The summer after leaving the nursery, I gave birth to a baby boy and, thanks be to God, he lived. We called him Henri-Luc after both his grandfathers, but he was always just Luc to me. Jean-Michel completed his apprenticeship at the palace stables and was appointed a charettier, driving supply wagons between Paris and the royal estates, which meant he was away a great deal. He was allocated family quarters at the palace, but my mother became increasingly crippled by painful swollen joints and I was needed at the bakery, which suited me fine, because for a time the Duke of Burgundy had kept his hands on the reins at the Hôtel de St Pol and after my terrifying encounter I preferred to stay as far from him as possible.

But city life wasn’t easy. No one lived in cosy harmony with their neighbours any more, for after Burgundy’s abduction of the royal children, Paris had become a sad and vicious place, its people divided into factions according to which of the royal affinities they supported or were dependent upon. Locked in their battle for power, the Dukes of Burgundy and Orleans lobbied and bribed all the various guilds and in the church and university. As a result, split loyalties tore society apart, causing a succession of riots and murders, burnings and lynchings, which brought terror to the streets. Officially the ailing King Charles still sat on the throne, but for long periods he was unable to command the loyalty of his lieges and, while attempting to rule in his stead, the queen played one duke off against another – as rumour had it both in and out of bed.

It must be said, looking back, that Catherine was well out of it, tucked safely away in her convent in the country, but I missed her like a limb. I knew I should forget her and that I would most likely never see her again, but every new stage of my own children’s lives reminded me of her. I loved Alys and Luc, of course I did, and as they grew older it was obvious that they loved me. Under their grandparents’ roof and with Jean-Michel coming and going, they were part of an outwardly tight-knit family unit, loyal to each other and loving, but for me they were also the source of an intense heartache, which I could confide in no one, for I knew that no one would understand or condone such maternal ambivalence.

Gradually my mother’s illness grew so bad that in the morning she could barely haul herself out of bed and spent most of the day sitting behind the open shutter of the shop telling me what to do and finding fault with my efforts. I knew she could not help it because the terrible pain in her swollen joints made her cry out in agony, but I found it hard to keep my temper with her and I have to confess I often failed. That she only ever scolded me, not my father or the children, did not help. Eventually she started taking a special remedy, which I would fetch for her from the apothecary. It was hard to believe how a syrup made from poppies could affect someone the way that potion affected my mother, but from the day she started taking it she was more or less lost to us. At first I was so grateful that it relieved her pain that I ignored her total lassitude and the vacant look in her eyes, but after several weeks I grew worried and secretly substituted another remedy. However, when she started shaking and vomiting and screaming for what she called her ‘angel’s breath’, I was forced to give in. One night I think she must have swallowed too much of it, or else the mixture was tainted in some way, because my father woke up to find her dead beside him.

We were both devastated, remembering the strong woman she had once been, but we were also thankful that her suffering was over. In some ways she was lucky to die in her bed, for at that time life in Paris was perilous and cheap. People were murdered simply for wearing the wrong colour hood or walking down the wrong alley. Bodies were found in the streets every day with their throats slit or their skulls cracked like eggs.

One freezing November night it was none other than the Duke of Orleans himself who was hacked to death, set upon by a masked gang in the Rue Barbette behind the Hôtel de St Antoine. He had been a frequent visitor at a mansion there, in which a lady, widely believed to be the queen, had been living for several weeks. As royal guards swarmed through the streets seeking the duke’s murderers, news spread that the corpse’s right hand had been severed at the wrist. Blue-hooded Burgundians declared this to be proof positive that Orleans had been in league with the devil, who always claimed the right hand of his acolytes. White-hooded Orleanists maintained, meanwhile, that the only devil involved in this murder was the Duke of Burgundy who, rather giving credence to this claim, abruptly quitted his coveted position of power beside the king and fled to Artois, destroying strategic bridges behind him. That left a power vacuum, which for the citizens of Paris was the most dangerous situation of all. In the gutters the body count mounted nightly.

My father knew the baker who delivered bread to the heavily guarded house in the Rue Barbette and it was he who told us that the lady the Duke of Orleans had visited so frequently and foolhardily had given birth to a baby and had only just survived. After the murder she too fled, no one knew how or where. The house was just suddenly empty. A few weeks later, a royal pronouncement told us that Queen Isabeau had given birth to another son, stating that the boy had been baptised Philippe and died soon afterwards.

My father and I wore brown hoods and kept our mouths shut. We managed to stay alive, but it was a daily struggle to keep the ovens fired. The brushwood we burned had always been collected by fuellers in the countryside, but desperate gangs of bandits and cut-throats made the gathering of it too dangerous. Flour supplies were another problem as factional armies were constantly on the move around Paris, purloining food stocks as they marched. Fortunately, Jean-Michel was often able to ‘divert’ sheaves of dry furze and sacks of flour to the bakery from supplies shipped in by barge to the royal palace. Yes, I am afraid we took to filching royal assets as freely as Madame la Bonne had done. It was the only way to survive.

After years of scheming and struggling to keep the bakery going, a sudden apoplexy carried off my father and even before we had buried him, the Guild of Master Bakers callously informed me that our license was revoked. It was pointless to protest. Women were not admitted into the guild and only guild members could bake bread. Although, as my father’s sole heir, I owned the ovens, I could not use them, nor could I safely live alone with my children in lawless Paris. So, lacking any choice, I let the house and bakery to one of our former apprentices and brought Alys and Luc to live with their father at the Hôtel de St Pol.

I was far from happy to be back, but at least Burgundy was no longer in charge. By then the dauphin – little Prince Louis who had dropped the hairy caterpillar down my bodice – had turned sixteen and taken his seat on the Royal Council, aided and abetted by his much older cousin, the Duke of Anjou. Between them they managed to prevent Burgundy and his cohorts from making any successful moves on Paris, but it wasn’t all good because the queen had clung onto her position and she and the dauphin had to share the regency. It was a daily feature of life at St Pol to see red-faced emissaries scuttling between the Queen’s House and the dauphin’s apartments, making futile attempts at building bridges between a mother and son who were constantly at loggerheads.

Not that I was one to talk. I have to admit that it wasn’t all peace and harmony between me and Jean-Michel. After the death of my mother, I had grown used to being mistress of my own home and helping to run a business. Now I was once more on servant’s wages and living in one damp, dark chamber with no grate and no garderobe. We peed in pots and had to use the reeking latrine ditch behind the stables. I grumbled constantly about my reduced circumstances, so no wonder Jean-Michel was glad to have news to cheer me up.

‘Not news of what,’ he countered. ‘Of who. Of the Princess Catherine.’

I sat bolt upright, wide awake. ‘Catherine! What about her? Tell me!’

Until he said her name I had not realised how starved I had been of her, my longing raw and secret, like a concealed ulcer.

‘She is coming back to the Hôtel de St Pol.’

‘When?’ I nearly screeched, rearing round and shaking him by the shoulder. ‘When, Jean-Michel?’

‘Shh!’ I could not see him in the dark, but I could sense the admonitory finger on his lips. ‘Sweet Jesus! Simmer down, woman, and I will tell you. Quite soon, I think. One of the grand master’s clerks was down at the stables today, making arrangements for her travel from Poissy Abbey.’

My mind was doing somersaults, but I tried to steady myself so that I could ponder this development. ‘I wonder why she is coming back now. There must be a reason. My God, Jean-Michel, will you be involved?’ There were occasions when he was called on to ride in the teams which carried the royal horse-litters.

‘No, no. She is the king’s daughter. There is to be a full escort – twenty knights and two hundred men-at-arms – too grand a job for me.’ Jean-Michel reached out to pull me down beside him. ‘I must find more things to get you excited,’ he murmured, nuzzling my ear, and being by now full of pent-up feelings, I reciprocated. But after we had stoked the spark of passion to a blaze and zestfully quenched it, I lay wide-eyed, my mind spinning like a windmill in a gale.

A few weeks previously, an embassy from England had arrived at the French court. A cardinal and two bishops, no less, had ridden in with great pomp and show, parading through the city with banners flying, trailing a huge procession of knights and retainers eager to enjoy the sights and brothels of Paris. It was a surprise to see them come in peace, because up to then we had heard tell that the English king was mobilising to re-claim territories on this side of the Sleeve, which he considered belonged to England. Normandy, Poitou, Anjou, Guienne, Gascony, they were all on his list. I remember wondering why he did not just claim the whole of France, the way his great-grandfather had done. Being a staunch royalist, my mother had told me how seventy years ago King Edward III of England had tried to claim the French throne as the nearest male heir to his uncle, King Charles IV of France, who had been his mother’s brother. But thirty years before that, in their own male interests no doubt, the grandees of Church and State had decided that women in France could not inherit land – pots and pans yes, horses, houses and gold yes, land no. They could not even pass land through their own blood line to their sons, pardieu! They called it Salic law, but my mother never explained why. Perhaps she did not know. Anyway, this law nullified King Edward’s claim and put Catherine’s great-grandfather on the French throne instead. Arguments over sovereignty had been rumbling between France and England ever since.