Полная версия

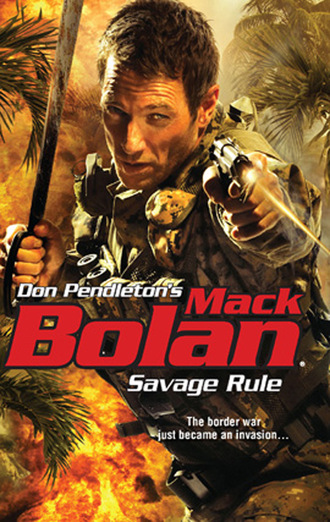

Savage Rule

It stood to reason; that was a common enough tactic among strong-arm dictators and their ilk. Creating a cadre of loyalists whose powers exceeded those of the regular military fostered a sense of fear among the lower echelons of a dictator’s power base, while shoring up—through preferential treatment and a sense of elite status—the core of men willing to fight and die for their leader. This had been, after all, the theory and concept behind Iraq’s Republican Guard, essentially a special-forces unit tasked with protecting Saddam Hussein’s regime as well as with the dictator’s most critical military operations. Republican Guard recruits were volunteers on whom many material perks were lavished. They’d enjoyed their often cruel jobs and were well rewarded for them. There was every reason to believe that Orieza’s shock troops were every bit as brutal and every bit as highly motivated.

Out here on the border, it was unlikely the prisoners were Honduran citizens. They could be Guatemalan troops lost in the previous forays made by Orieza’s raiders. They might even be Honduran soldiers accused of disloyalty, real or imagined. Hard-line regimes like Orieza’s were notorious for their paranoia, Bolan knew. It didn’t matter. The advance camp had to be destroyed, and completely, for the Executioner’s daring one-man blitz through Honduras to succeed. It was merely the second step in a chain of raids that would take him, before he was done, to the heart of Orieza’s government… But first things first. Whoever the prisoners were, Bolan would make sure they were freed. And before he was done, their torturers would answer in full for what had been inflicted upon those captives screaming in the night.

Bolan crept along the brush line until he found a suitable target: a sentry who had ranged just a little too far from his sandbag nest, smoking a truly gigantic, cheap cigar that was producing large volumes of blue smoke. From the banter being exchanged in stage whispers between the sentry and his compadre still in the machine-gun emplacement, it was clear that the fumes were objectionable to the second man; hence the smoker’s distance from his post. Bolan listened to them trade vulgar insults in Spanish. There were at least a few threats. Both men, if Bolan heard them correctly, were vowing to stab each other. Shaking his head and questioning his fellow soldier’s parentage, the sentry with the cigar grudgingly moved a few paces farther.

Perfect.

Bolan removed a simple fork of carbon fiber from a ballistic nylon pouch on his belt. He unsnapped the wrist brace and attached a heavy, synthetic rubber band to the two posts of the fork. Then he produced a small ball bearing from the belt pouch, placed it in the wrist-brace slingshot he held and stretched the band taut.

The sentry turned away, sucking in a deep mouthful of smoke. When the tip of the cigar flared orange-red, Bolan let fly.

The ball bearing snapped the man in the neck, hard. The sentry swore and slapped at the spot. His cigar fell down the front of his uniform, spraying dull orange sparks, and he slapped at them, as well, cursing quietly. He was reasonably discreet nonetheless. No doubt he would be disciplined, perhaps harshly, for drifting from his post to enjoy a late-night smoke.

“Come here!” Bolan whispered in Spanish, beckoning from the cover of the brush and hoping the man could see his arm despite the damage the burning cigar would had done to the sentry’s night vision. “You have to take a look at this. Hurry!”

“What?” the man whispered, confused. “Tomas?” He stepped forward hesitantly.

“Hurry up!” Bolan urged.

The sentry’s curiosity, and perhaps some overconfidence characteristic of Orieza’s raiders—who, after all, had met little resistance from the disorganized Guatemalan troops—got the better of him. He groped for his cigar, picked it up and hurried forward, firing a series of whispered questions in Spanish. Bolan couldn’t catch it all, but he gathered the sentry thought this was some practical joke played by a friend in his unit, the “Tomas” he kept naming.

Up close, Bolan could see this man wore the blue epaulets of the shock troops. The joke was on the sentry, all right.

Once he was in range, Bolan struck. He reached for the man as fast as a rattler uncoiling, and grabbed him by the shoulder and the face, his fingers jabbing up and under the sentry’s jawline. The sudden move brought a gasp of surprise from Bolan’s target as the man hit the ground like a sack of wet cement. The big American lifted his hand from the man’s jaw and slashed down savagely with the smaller of his two fighting knives, silencing the sentry forever.

Wiping the gory blade on the dead man’s uniform, Bolan searched him and found what he wanted: the sentry’s radio. Then he drew the suppressed Beretta 93-R, crouched to brace his elbow against his knee, and waited for the sentry’s cigar-hating fellow trooper to pop his head up over the sandbags. The fact that an alarm hadn’t already been raised was proof that nobody had seen the Executioner grab the man in the shadows. Now, when the cigar-smoking soldier was nowhere to be found, it shouldn’t take long for the other soldier to wonder where he went.

It didn’t. The curse in Spanish was another loud stage whisper, and when the Honduran soldier propped himself up above the sandbags to call to his wayward comrade, Bolan put a silenced 147-grain 9-mm hollowpoint through the man’s brain.

Working his way in the darkness across the cleared perimeter as far as he dared, he found Claymore mines placed at intervals to cover the dead soldiers’ position at the southwest. No doubt there were more mines similarly spaced all around the advance camp. He kept an eye on the crow’s nest of the tower on that corner of the base as he crawled back the way he’d come. The guard appeared to be slumped in his metal enclosure, possibly napping.

The combat clock was ticking, now. The Executioner had no idea on what schedule the perimeter guards called in, or if they did at all, but it was standard military procedure to do so. He worked his way around the perimeter of the camp as stealthily as he could. When he faced the north side of the camp, he was ready. He picked up his stolen radio, keyed it twice, then started groaning into it.

Answering chatter in Spanish came immediately. Bolan keyed the mike a few more times, as if having trouble with it, and then muttered something about dying. He managed to dredge up the appropriate terminology, again in Spanish, and hissed into the radio as if with his dying breath, urging his brave comrades to activate the mines guarding the southwest machine-gun emplacement.

The camp came alive. Searchlights on the towers buzzed to life and began sweeping the no-man’s-land around the base, while somewhere inside, a hand-cranked siren slowly worked its way to a gravelly, mechanical wail. Bolan could hear the shouts of alarmed soldiers grow in intensity. He pictured them finding the dead soldier behind his sandbags, next to his machine gun. Their fears confirmed, they would reach for the Claymore detonator nearby, if not clutched in the dead man’s hand….

The thumps of the Claymores detonating were followed by screams even more horrifying than those that had stopped coming from the interrogation building in the midst of the camp. They would be from the Honduran soldiers responding to the alert—where Bolan had reversed the Claymore mines he had found, the shaped charges directing their deadly ball-bearing payload inward over the machine-gun emplacements rather than outward from the palisade.

Blind reaction fire erupted from several locations outside the camp and from within the perimeter. The noise was deafening. Several other Honduran soldiers triggered their own Claymores, apparently fearing an unseen enemy was advancing on their positions. Bolan, well clear of the mines from his location beyond the no-man’s-land, was in no danger. This was the moment of frenetic panic he required—and the moment he had engineered.

He methodically loaded and fired the M-203. It was a difficult shot, but his first 40-mm fragmentation grenades struck true, blowing apart the crow’s nest of the watchtower closest to his position. He worked his way out, dropping a grenade into the midst of the camp, then annihilating another of the guard towers.

Bolan fired a grenade into the middle of the no-man’s-land. He was rewarded with the thumps of Claymores again. He sent another 40-mm payload downrange, but there were no more explosions; the Claymores had been fired, and now the way was clear. He moved easily through the darkness, avoiding the wild firing of the machine guns as he slipped through. As he had expected, Third World soldiers who were brave when facing out-gunned opponents were quick to break discipline and give in to fear when faced with a determined aggressor. Gaining and keeping the battlefield momentum, the initiative in an engagement, was Bolan’s stock in trade. He was very good at what he did.

He leveled his rifle and sprayed bursts of 5.56-mm fire into the guards manning the nearest machine gun. They didn’t appear even to notice him, until it was too late. Their attention was focused inward, on the base itself. Bolan loaded his grenade launcher once more and blew a hole in the palisade large enough for him to enter the camp.

The explosion drew fire, but the Executioner ignored it, throwing himself through the splintered gap and rolling with the impact. He came up firing, stitching the confused, surprised shock troopers he encountered. As he ran, he yanked smoke grenades from his harness and threw them. The plumes of dense, green-yellow smoke added to the confusion and helped further cover his movements.

Working his way through the camp, he exhausted his supply of 40-mm grenades, blowing apart as many pieces of equipment and protective structures as he could, while always avoiding the roughly centered prefab hut he had dubbed the holding cell. He finished destroying the watchtowers and punched several holes in the protective palisade. There was nothing to be gained by destroying the wooden walls themselves, but no harm in allowing it to happen, either.

Resistance was ineffectual, as he had expected it to be. Most of the troops from the advance camp had, as was only logical, been assigned to the raiding column massing at the border. This base was, after all, the staging area that permitted the raiders to do what they had come to do. A token force had been left behind to guard it, but it was clear they had expected nothing serious by way of retaliation.

If they had been alerted by their loss of radio contact with the raiding party, nothing about their reaction to Bolan’s assault indicated so. It took him a little while, nonetheless, to work his way through the camp and eliminate any stragglers. He took down several men wearing the blue epaulets of the shock troopers, some of them in the act of fleeing, while others stood their ground in the smoke and flames and tried to take him. It didn’t matter, either way. These men might be the elite of Orieza’s killers and the best the dictator could field, but they weren’t in the same class as the Executioner.

Thinking of radio contact reminded him to check the radio room, which he recognized by the small, portable transmitting array jerry-rigged to the top of a corrugated metal shack in the northwest corner of the palisade’s interior. Inside, Bolan expected to find a man or men desperately screaming for help, but the shack was empty. The radio equipment was undamaged, so the big American emptied the last of his rifle’s ammo into it. He dropped the magazine, slapped home a spare, then picked his way through the wreckage of the base interior once more. As he moved he was mindful of the dangers, for there still could be men hidden between him and the holding cell.

Nevertheless, the man who threw himself from concealment next to a burning military-style jeep almost managed to take Bolan by surprise. He was incredibly fast, with a sinewy build that translated into a painful blow as the tall man drove a bony elbow into Bolan’s chest. The Executioner allowed himself to fall back, absorbing the hit as he let his rifle fall, and moved to draw one of his knives….

The man surprised Bolan by leaping over him and continuing to flee. The Executioner rolled over and regained his footing, snapping up the rifle and trying to line up the shot. He caught a glimpse of the thin, hatchet-faced man as the evidently terrified Honduran soldier bolted through the smoke, running as if the devil himself were close behind. Bolan didn’t bother to try for the shot; the angle was bad, and too much cover stood between him and the rapidly fleeing trooper. Just as he had been unconcerned with a radio distress call, the Executioner wasn’t worried about a soldier or two running for help. By the time Orieza’s forces could muster a relief effort, Bolan would be long gone.

A bit chagrined despite himself, he was even more vigilant as he advanced on the holding cell. A heavy wooden bar set in steel staples secured the door. He lifted the bar and tossed it aside. The door couldn’t be opened from the inside, which meant there would be no guards within—unless their own people had locked them inside with the prisoners.

“Step away from the door!” he ordered in Spanish, careful to stand well aside. He let his rifle fall to the end of its sling, and drew both his Beretta and his portable combat light, holding the machine pistol over his off-hand wrist. There were no answering shots from within, so he chanced it and planted one combat boot against the barrier. The heavy door opened, and Bolan swept the dimly lit interior.

What he saw hardened his expression and brought a righteously furious gleam to his eyes. There were half a dozen men and women, ranging from their late teens to quite old, hanging by their wrists from chains mounted in the ceiling. They had been repeatedly flogged. A leather whip was hanging in the center of the room, from a nail set in a post that helped support the corrugated metal ceiling.

“Señor,” an older man called, his eyes bright. He fired off a sentence in Spanish so rapid that Bolan couldn’t catch it.

Bolan went to him. “Easy,” he said. “I’m going to let you down. It’s over. Ha terminado.”

“You are American?” the man asked in English.

Bolan looked at him, pulling the pin that secured the chains. The old man fell briefly to his knees before Bolan helped him up. “I’m a friend,” he said.

“You are sent from God.” The old man smiled. “And you are an American.”

Bolan didn’t answer that. Instead, he said, “Can you walk?”

“I can walk.” The man nodded. His lightweight clothes were bloody and ragged, stained a uniform dirty brown, and clearly, he had suffered badly at the hands of Orieza’s men. But he stood tall and defiant under Bolan’s gaze. “What is your name?”

“Just call me ‘friend.’”

“I am Jairo,” the old man said. He grinned. “Amigo.”

Bolan gestured to the others, who were watching with an almost eerily uniform silence. “Help me with them,” he said simply.

“Of course,” Jairo said. “Do not worry about them, amigo. They were strong. They will be all right.”

“Does anyone need medical attention?”

“I will make sure they get it,” Jairo said. “Our village is not far.”

“Village? Where?” Bolan asked.

He pointed. “Over the border.”

“You’re from Guatemala?”

“Sí. The soldiers raided our village and took us prisoner two days ago. It has been a very long two days.” Jairo worked his way among the others with Bolan, freeing the captured villagers from their chains. From what Bolan could see, the victims had indeed been cruelly tortured.

“You were fed? Given water?” he asked.

“Sí.” Jairo nodded.

That was interesting. Bolan completed his survey of the villagers. Many had bad wounds on their backs, and a couple, including Jairo, sported cigar and cigarette burns, but the damage was largely superficial. There had been no intent to kill these people.

“Jairo, did your captors say anything? Did they explain why they took you, or what they wanted from you?”

“No,” Jairo replied, shaking his head. “Nothing. Only that we would do well to tell others, if we lived, just what General Orieza will do to us if his men are resisted.”

So that was it, Bolan mused. Orieza and his people were pursuing an explicit strategy. It wasn’t atrocities for the sake of atrocities; Orieza’s shock troopers were softening up the resistance, both within Honduras and across the border, by instilling fear in the populations of both nations. Combined with the military raids, it was a very good strategy, from Orieza’s perspective. It would enable him to continue rolling over the Guatemalans and probably guarantee at least some cooperation, if not simply a lack of interference from the frightened locals.

“Did he say he might release some or all of you?” Bolan asked.

“No,” Jairo shook his head again. “But I think he would have. His heart, it did not seem to be in it. El Alto had a cruel look to him. He was not so soft as to let us live unless he meant to.”

“Who? ‘The Tall One’?”

“Sí,” Jairo said. “It was El Alto who did the whipping, and the talking. Always him. Never the other soldiers. I think he liked it. He looked, in his eyes, as if he enjoyed it.” Jairo shook his head yet again and spit on the ground in disgust. “He left not long before you found us. Had he wished, he could have cut our throats.”

A tall, cruel-looking man. It was very likely that El Alto, this torturer, was the same Honduran soldier Bolan had seen fleeing the camp. He made a mental note of that. If luck and the mercurial gods of combat were with him, he would encounter The Tall One again.

“Come on,” Bolan said to the old man. “Let’s get your people gathered together, treat their wounds and move them out. Can any of you handle a weapon?”

There were a few murmurs of assent. Jairo grinned. “We are not so helpless. We can see ourselves safely home. We will take what we need from the soldiers,” he said. “The ones who are outside.” He nodded to the door. “The ones you killed.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because you, too, have a look in your eyes, amigo.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Sí.” Jairo nodded solemnly. “Su mirada es muerte. Your look is one of death.”

CHAPTER FOUR

The blue-tagged shock-troop guards outside General Orieza’s office snapped to attention as Roderigo del Valle stalked down the corridor. Dawn had broken, yellow and inviting, the sun’s rays streaming through the floor-to-ceiling windows on either side of the corridor. This had no effect on Del Valle, who carried with him a darkness that no light could penetrate. At least, this was how he preferred to be seen. Better to be feared than loved when one of the two must be lacking, as the old saying went….

He swept past the guards as if he barely saw them, and in truth, he didn’t. It had been a very long, very frustrating night, and he hadn’t yet even begun to catalog the damage dealt to their operation on the Guatemalan border. He snarled in reply as one of the guards greeted him respectfully and managed to get the door open before Del Valle rammed it, for the tall, hatchet-faced man didn’t break his stride as he made his way into the anteroom of General Orieza’s private lair.

Orieza’s secretary glanced up, her face as pretty but as stupid as ever. She pursed her lips and greeted him quietly. Her eyes were full of fear, and that pleased him, for she was only too aware of what he could do to her if he chose. Orieza wouldn’t object, at least not too loudly, if Del Valle decided to use the woman and throw her away. Another just like her, even prettier, would be sitting in her chair come the next dawn.

It wasn’t that Del Valle didn’t have his own needs, where women were concerned. He had them on occasion, and when he did, the union was brief and brutal. He had little use for a woman clinging to his arm and making demands of his time; what man would put up with such impositions, truly? And he had no respect for the empty-headed trollops who invariably did serve his purposes. How any man chose to saddle himself with a woman’s constant whining and complaining, he didn’t know. Orieza himself had been married, not so very long ago, and the woman had grated on Del Valle’s nerves. She was forever bitching to Orieza about whatever whims came to her head, demanding his time and diminishing his focus. It had been a relief when Orieza had finally confided to his chief adviser that the general found his wife somewhat of a nuisance. Del Valle had jumped at the chance to arrange an “accident” for the miserable harpy. And Orieza, while he suspected that Mrs. Orieza’s car didn’t perhaps roll over of its own accord that fateful morning, hadn’t asked many questions. The old man was content to spend his time with the slatterns Del Valle’s lieutenants dug up for him. He tired of them quickly, and more than once Del Valle had made use of these castoffs before leaving their broken bodies on the floor for his men to clean up…. But such were the privileges of power.

He paused to survey himself in the full-length mirror that dominated one wall of the opulently appointed anteroom, while the woman fidgeted nervously. He ignored her. His angular, lined face looked back at him as he tried to smooth the creases in his uniform. He wore the same fatigues as did his shock troops, with no insignia of rank whatever. This was an affectation, but a deliberate one. No strutting peacock to dress himself in worthless ribbons and medals, or gold braids and colorful cloth, Del Valle preferred instead to let what he could do speak for itself. His shock troops were loyal to him, and him first, for he had proved time and again that he would deal violently with any challenge to his authority. When the time came, even General Orieza would learn that the blue epaulets on the shoulders of those armed guards surrounding him bespoke devotion to Roderigo del Valle, and not to their “general,” but by then… Well, by then, it would be too late for poor Ramon.

Del Valle frowned at the widow’s peak of stubble prominent on his forehead; it was time to shave his head once more. This was, however, the least of his concerns. His eyes were bloodshot, his uniform stained and torn. He hadn’t paused to change or truly to right himself after making the trip here, using the SUV he had hidden near the advance camp for just that purpose. There had been no time. By now, Castillo’s spies within the ranks of Orieza’s people—and Del Valle knew the Mexican president had them, for he permitted them to remain—would know that the general’s troops had suffered a serious setback on the Guatemalan border. Orieza would have to speak with Castillo, and that meant El Presidente himself would be phoning. Orieza couldn’t be permitted to take the call alone. He would need Del Valle on hand, lest the simpering old fool lose his nerve and back out of the plan.

Del Valle would give his general the courage he needed in dealing with the Mexican. That would be simple enough. Explaining to the general what had happened in the simplest, most casual terms would require a more delicate balancing act. Orieza had to know; it couldn’t be kept from him, lest the fact of Del Valle’s power behind the old man’s throne become too apparent to those with whom the General dealt regularly. There was no benefit to pulling a puppet’s strings if your audience focused on the puppeteer.

Del Valle knew that others considered him paranoid; he had been told as much, by many fools who this day didn’t draw breath. He dismissed them. To hold power, true power, required that one not be the constant target of assassins. Doing what was necessary carried with it many dangers and made many enemies. His shock troops were now camped about the general’s residence, a standing army devoted simply to keeping the old man safe. Let Orieza be a prisoner in his own home, content to play with his women and believing he was commanding legions. Del Valle would be there to reap the true benefits, forever in control, never far from the shadows.

Roderigo had risen through the ranks of the Honduran military, always unofficial, always an “adviser” or a consultant to men of power. Attaching himself to Orieza’s coattails had been simple enough, becoming known and respected as his adviser easy. The old man was handsome and well liked, a silver fox who, in his younger days, had shown much brilliance and inspired much loyalty. But Orieza was no saint. He knew and valued the services a ruthless agent could provide, and Del Valle shrewdly and masterfully played to the old man’s ego while bolstering his failing courage. Creating the shock troops, training them and assigning them their missions had been Del Valle’s brilliant move, and it had served them both well. Orieza liked believing he was protected by a private army within the Honduran military. The shock troops, meanwhile, were fiercely loyal to the man who had elevated them to elite status, to wealth, to almost unlimited license within the world permitted to them. Special privileges, women, weapons, money…the shock troops knew that they benefited greatly from the arrangement. They also knew that these things were conferred on them not by Orieza, but by Roderigo Del Valle.