Полная версия

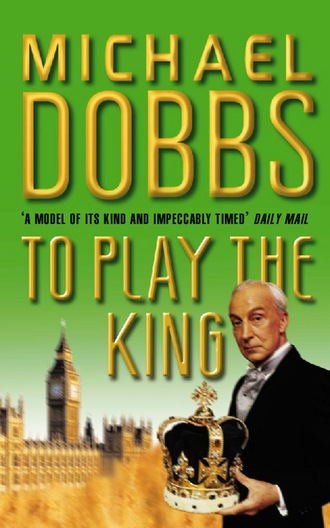

To Play the King

MICHAEL DOBBS

TO PLAY THE KING

Copyright

This is entirely a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1992

Copyright © Michael Dobbs 1992, 2014

Michael Dobbs asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content or written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006471646

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2015 © ISBN: 9780007397617

Version: 2019-01-15

Praise for To Play the King:

‘With a friend like Michael Dobbs, who on earth needs enemies? Gloriously cheeky. Dobbs’ books grab because of their authenticity’

The Times

‘Highly readable…a model of its kind and impeccably timed’

Daily Mail

Lucy and Andrei

For Medford 1971. For Fiskardon 1981.

For Villars 1991.

For Everything.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue

PART ONE

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

PART TWO

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

PART THREE

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Epilogue

Keep Reading

About the Author

By Michael Dobbs

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

When I wrote To Play the King in 1990 as a sequel to House of Cards, it was partly because I believed that the Royal yacht was heading for turbulent waters. And so it proved to be. I wrote about fractured marriages, financial scandal, political controversy and public humiliations, and for the next few years the Royal Family seemed to follow the script with breathless tenacity. At times it seemed as though various individuals were openly auditioning for parts in the story. If my book was intended to be by way of a warning, as I suppose it was, it failed completely. The House of Windsor was to endure some of its worst moments. The yacht nearly sank and some members of the crew were thrown overboard.

My fictional king isn’t simply a version of Prince Charles – there have been many heirs to the throne who have got themselves into difficulties and I took a little inspiration from more than one – but it was inevitable that some comparisons would be made. At the time I began writing, it was clear that his marriage was falling apart, despite all the official denials, so I decided that my kingly character would have no wife. I hope none of what I wrote amounted to disrespect because that is not what I intended.

In any event, despite those dire years, both he and the institution have displayed their tenacity and powers of recovery, and today they stand higher in public esteem than they have for decades. The Royal yacht sails on.

And so does FU. Nearly thirty years after I created him, he has developed a life of his own, in books, on global television, as a character who has been quoted both in Parliament and the press. Do you suspect he might even have been muttered about in the corners of various palaces? Well, you might say that but I am not going to comment…

M.D. 2013

PROLOGUE

Away with Kings. They take up too much room.

It was the day they would put him to death.

They led him through the park, penned in by two companies of infantrymen. The crowd was thick and he had spent much of the night wondering how they would react when they saw him. With tears? Jeers? Try to snatch him to safety or spit on him in contempt? It depended who had paid them best. But there was no outburst; they stood in silence, dejected, cowed, still not believing what was about to take place in their name. A young woman cried out and fell in a dead faint as he passed, but nobody tried to impede his progress across the frost-hard ground. The guards were hurrying him on.

Within minutes they were in Whitehall, where he was lodged in a small room. It was just after ten o’clock on a January morning, and he expected at any moment to hear the knock on the door that would summon him. But something had delayed them; they didn’t come until nearly two. Four hours of waiting, of demons gnawing at his courage, of feeling himself fall to pieces inside. During the night he had achieved a serenity and sense of inner peace, almost a state of grace, but with the heavy passage of unexpected minutes, growing into hours, the calm was replaced by a sickening sense of panic which began somewhere in his brain and stretched right through his body to pour into his bladder and his bowels. His thoughts became scrambled and the considered words, crafted with such care to illuminate the justice of his cause and impeach their twisted logic, were suddenly gone. He dug his finger nails deep into his palms; somehow he would find the words, when the time came.

The door opened. The captain stood in the dark entrance and gave a curt, sombre nod of his helmeted head. No need for words. They took him and within seconds he was in the Banqueting Hall, a place he cherished with its Rubens ceiling and magnificent oaken doors, but he had difficulty in making out the details through the unnatural gloom. The tall windows had been partially bricked up and boarded during the war to provide better defensive positions. Only at one of the farther windows was there light where the masonry and barricades had been torn down and a harsh grey glow surrounded the hole, like the entrance to another world. The corridor formed by the line of soldiers led directly to it.

My God, but it was cold. He’d had nothing to eat since yesterday, he’d refused the meal they had offered, and he was grateful for the second shirt he had asked for, to prevent him shivering. It wouldn’t do to be seen to shiver. They would think it was fear.

He climbed up two rough wooden steps and bowed his head as he crossed the threshold of the window, onto a platform they had erected immediately outside. There were half a dozen other men on the freshly built wooden stage while every point around was crammed by teeming thousands, on foot, on carriages, on roofs, leaning from windows and other vantage points. Surely now there would be some response? But as he stepped out into the harsh light and their view, their restlessness froze in the icy wind and the huddled figures stood silent and sullen, ever incredulous. It still could not be.

Driven into the stage on which he stood were four iron staples. They would rope him down, spread-eagled between the staples, if he struggled, yet it was but one more sign of how little they understood him. He would not struggle. He had been born to a better end than that. He would but speak his few words to the throng and that would be sufficient. He prayed that the weakness he felt in his knees would not betray him; surely he had been betrayed enough. They handed him a small cap into which with great care he tucked his hair, as if preparing for nothing more than a walk through the park with his wife and children. He must make a fine show of it. He dropped his cloak to the ground so that he might be better seen.

Heavens! The cold cut through him as if the frost were reaching for his racing heart and turning it straightway to stone. He took a deep, searing breath to recover from the shock. He must not tremble! And there was the captain of his guard, already in front of him, beads of sweat on his brow despite the weather.

‘Just a few words, Captain. I would say a few words.’ He racked his mind in search of them.

The captain shook his head.

‘For the love of God, the commonest man in all the world has the right to a few words.’

‘Your few words would be more than my life is worth, Sir.’

‘As my words and thoughts are more than my life to me. It is my beliefs that have brought me to this place, Captain. I will share them one last time.’

‘I cannot let you. Truly, I am sorry. But I cannot.’

‘Will you deny me even now?’ The composure in his voice had been supplanted by the heat of indignation and a fresh wave of panic. It was all going wrong.

‘Sir, it is not in my hands. Forgive me.’

The captain reached out to touch him on the arm but the prisoner stepped back and his eyes burned in rebuke. ‘You may silence me, but you will never make me what I am not. I am no coward, Captain. I have no need of your arm!’

The captain withdrew, chided.

The time had come. There would be no more words, no more delay. No hiding place. This was the moment when both they and he would peer deep inside and discover what sort of man he truly was. He took another searing lungful of air, clinging to it as long as he could as he looked to the heavens. The priest had intoned that death was the ultimate triumph over worldly evil and pain but he discovered no inspiration, no shaft of sunlight to mark his way, no celestial salvation, only the hard steel sky of an English winter. He realized his fists remained clenched with the nails biting into the flesh of his palms; he forced his palms open and down the side of his trousers. A quiet prayer. Another breath. Then he bent, thanking God that his knees still had sufficient strength to guide him, lowering himself slowly and gracefully as he had practised in his room during the night, and lay stretched out on the rough wooden platform.

Still from the crowd there came no sound. His words might not have lifted or inspired them, but at least they would have vindicated. He was drenched in fury as the overwhelming injustice of it all hit him. Not even a chance to explain. He looked despairingly once more into the faces of the people, the men and women in whose name both sides had fought the war and who stood there now with blank stare, ever uncomprehending pawns. Yet, dullards all, they were his people, for whose salvation he was bound to fight against those who would corrupt the law for their own benefit. He had lost, but the justice of his cause would surely be known in the end. In the end. He would do it all again, if he had another chance, another life. It was his duty, he would have no choice. No more choice than he had now on this bare wooden stage, which still smelt of resin and fresh sawdust. And they would understand, wouldn’t they? In the end…?

A plank creaked beside his left ear. The faces of the crowd seemed frozen in time, like a vast mural in which no one moved. His bladder was going – was it the cold or sheer terror? How much longer…? Concentrate, a prayer perhaps? Concentrate! He set on a small boy, no more than eight years old, in rags, with a dribble of crumbs on his dirt-smeared chin, who had stopped chewing his hunk of loaf and whose innocent brown eyes had grown wide with expectation and were focused on a point about a foot above his head. By God, but it was cold, colder than he had ever known! And suddenly the words he had fought so hard to remember came rushing back to him, as though someone had unlocked his soul.

And in the year sixteen hundred and forty-nine, they took their liege lord King Charles Stuart, Defender of the Faith and by hereditary right King of Great Britain and Ireland, and they cut off his head.

In the early hours of a winter’s day, in a bedroom overlooking the forty-acre garden of a palace which hadn’t existed at the time Charles Stuart took his walk into the next life, his descendant awoke with a start. The collar of his pyjama shirt clung damply and he lay face-down on a block-hard pillow stained with sweat, yet he felt as cold as…As cold as death. He believed in the power of dreams and their ability to unravel the mysteries of the inner being, and it was his custom on waking to write down everything he could remember, reaching for the notebook he kept for the purpose beside his bed. But not this time. There was no need. He would never forget the smell of the crowd mixed with resin and sawdust nor the heavy metallic colour of the sky on that frost-ridden afternoon. Nor the innocent, expectant brown eyes of a boy with a dirty chin smeared with crumbs. Nor that feeling of terrible despair that they had kept him from speaking out, rendering his sacrifice pointless and his death utterly in vain. He would never forget it. No matter how hard he tried.

CHAPTER ONE

Never cross an unknown bridge while riding an elephant.

(Chinese proverb)

December: The First Week.

It had not been a casual invitation, he never did anything casually. It had been an insistent, almost peremptory call from a man more used to command than to cajolement. He expected her for breakfast and it would not have crossed his mind that she might refuse. Particularly today, when they were changing Prime Ministers, one out and another in and long live the will of the people. It would be a day of great reckoning.

Benjamin Landless opened the door himself, which struck her as strange. It was an apartment for making impressions, overdesigned and impersonal, the sort of apartment where you’d expect if not a doorman then at least a secretary or a PA to be on hand, to fix the coffee, to flatter the guests while ensuring they didn’t run off with any of the Impressionist paintings enriching the walls. Landless was no work of art himself. He had a broad, plum-red face which was fleshy and beginning to sag like a candle held too near the flame. His bulk was huge and his hands rough, like a labourer’s, with a reputation to match. His Chronicle newspaper empire had been built by breaking strikes as well as careers; it had been as much he as anyone who had broken the career of the man who was, even now, waiting to drive to the Palace to relinquish the power and prestige of the office of Prime Minister.

‘Miss Quine. Sally. I’m so glad you could come. I’ve wanted to meet you for a long time.’

She knew that to be a lie. Had he wanted to meet her before he would most certainly have arranged it. He escorted her into the main room around which the penthouse apartment was built. Its external walls were fashioned entirely of high-impact glass, which offered a magnificent panorama of the Parliament buildings across the Thames, and half a rain forest seemed to have been sacrificed to cover the floor in intricate wooden patterns. Not bad for a boy from the back streets of Bethnal Green.

He ushered her towards an oversized leather sofa in front of which stood a coffee table laden with trays of piping-hot breakfast food. There was no sign of the hidden helper who must only recently have prepared the dishes and laid out the crisp linen napkins. She declined any of the food but he was not offended. He took off his jacket and fussed about his own plate while she took a cup of black coffee and waited.

He ate his breakfast in single-minded fashion; etiquette and table manners were not his strong points. He offered little small talk, his attention focused on the eggs rather than on her, and for a while she wondered if he might have decided he’d made a mistake in inviting her. He was already making her feel vulnerable.

‘Sally Quine. Born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Aged thirty-two, and a girl who’s already made quite a reputation for herself as an opinion pollster. In Boston, too, which is no easy city for a woman amongst all those thick-headed Micks.’ She knew all about that; she’d married one. Landless had done his homework, had pawed over her past; he wanted to make that clear. His eyes searched for her reaction from beneath huge eyebrows tangled like rope. ‘It’s a lovely city, Boston, know it well. Tell me, why did you leave everything you’d built there and come to England to start all over again? From nothing?’

He paused, but got no reply. ‘It was the divorce, wasn’t it? And the death of the baby?’

He saw her jaw stiffen and wondered whether it was the start of a storm of outrage or a move for the door. But he knew there would be no tears. She wasn’t the type, you could see that from her eyes. She was not unnaturally slim and pinched as the current fashion demanded, her beauty was more classical, the hips perhaps a half-inch too wide but all the curves well defined. She was immaculately presented. The skin of her face was smooth, darker and with more lustre than any English rose, the features carefully drawn as though by a sculptor’s knife. The lips were full and expressive, the cheekbones high, her long hair thick and of such a deep shade of black that he thought she might be Italian or Jewish. Yet her most exceptional feature was her nose, straight and a fraction long with a flattened end which twitched as she talked and nostrils which dilated with emphasis and emotion. It was the most provocative and sensuous nose he had ever seen; he couldn’t help but imagine it on a pillow. Yet the eyes disturbed him, didn’t belong on this face. They were shaped like almonds, full of autumnal russets and greens, translucent like a cat’s, yet hidden behind oversized spectacles. They didn’t sparkle like a woman’s should, like they probably once had, he thought. They had an edge of mistrust, as if holding something back.

She looked out of the window, ignoring him. Christmas was but a couple of weeks away, yet there was no seasonal cheer in the air. The festive spirit lay discarded in the running gutters, and somehow it didn’t seem a propitious day for changing Prime Ministers. A seagull beaten inland by North Sea storms cartwheeled outside the window, its shrieks and insults penetrating the double-glazing, envying them their breakfast before finally tumbling away through the blustery sky. She watched it disappear into the greyness.

‘Don’t expect me to be upset or offended, Mr Landless. The fact that you have enough money and clout to do your homework doesn’t impress me. Neither does it flatter me. I’m used to being chatted up by middle-aged businessmen.’ The insult was intended; she wanted him to know he wasn’t going to get away with one-way traffic. ‘You want something from me. I’ve no idea what but I’ll listen. So long as it’s business.’

She crossed her legs slowly and deliberately so that he would notice. From her days as a child she had had no doubts that men found her body appealing and their excessive attention meant she had never had the opportunity to treat her sex as something to treasure, only as a tool to carve a path through a difficult and ungenerous world. She had decided long ago that if sex were to be the currency of life then she would turn it into a business asset, to open the doors which would otherwise be barred. And men could be such reliable dickheads.

‘You’re very direct, Miss Quine.’

‘I prefer to cut through it rather than spread it. And I can play your game.’ She sat back into the sofa and began counting off the carefully manicured fingers of her left hand. ‘Ben Landless. Age…well, for your well-known vanity’s sake, let’s say not quite menopausal. A rough son-of-a-bitch who was born to nothing and now controls one of the largest press operations in this country.’

‘Soon to be the largest,’ he interrupted quietly.

‘Soon to take over United Newspapers,’ she said, nodding, ‘when the Prime Minister you nominated, backed and got elected virtually single-handed takes over in a couple of hours’ time and waves aside the minor inconvenience of his predecessor’s mergers and monopolies policy. You must’ve been celebrating all night, I’m surprised you had the appetite for breakfast. But you have the reputation of being a man with insatiable appetites. Of all kinds.’ She spoke almost seductively in an accent that had been smoothed and carefully softened but not obliterated. She wanted people to take notice and to remember, to pick her out from the crowd. So the vowels were still New England, a shade too long and lazy for London, and the sentiments often rough as if they had been fashioned straight from the dole queues of Dorchester. ‘So what’s on your mind, Ben?’