Полная версия

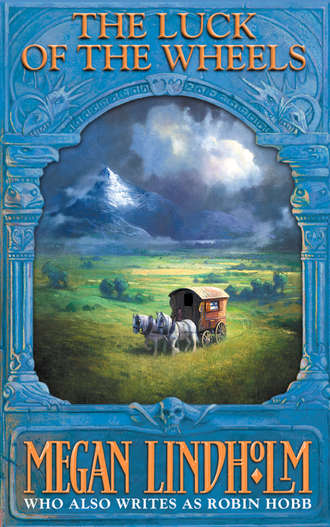

Luck of the Wheels

‘Is this as fast as they go?’ Goat demanded petulantly.

‘Mmm,’ Ki nodded. ‘But they go all day, and we get there just the same.’

‘Don’t you ever whip them to a gallop?’

‘Never,’ Ki lied, forestalling the conversation. Vandien was scarcely listening. His attention was focused on a street phenomenon. As Ki’s wagon rolled leisurely down the street, all eyes were drawn to it. And as quickly pulled away. All marked Goat’s passage, but no one called a genial farewell, or even a “Good riddance!”’ They ignored him as diligently as they would a scabrous beggar. Not hatred, Vandien decided, nor loathing, nor anything easy to understand. More as if each one felt personally shamed by the boy. Yet that made no sense. Could they have done something to the lad that they all regretted? Some act of intolerance carried too far? Vandien had once passed through a town where a witless girl had been crippled by the idle cruelty of some older boys. She had sat enthroned by the fountain, clad in the softest of raiment, messily eating the delicacies sent anonymously out to her. The focus of the town’s shame and penitence, but still untouchable. This thing with Goat was kin to that somehow. Vandien was sure of it.

‘But they could gallop if they had to?’ Goat pressed.

‘I suppose so,’ Ki replied, her tone already weary. Two more weeks of this, Vandien thought, and sighed.

The black mongrel came from nowhere. One moment the street was quiet, folk trading in the booths and tents of this market strip, all eyes carefully bowed away from Ki’s wagon. The next instant, the little dog darted out of the crowd, yapping wildly at the team. Sigurd flicked his ears back and forth, but calm Sigmund continued to plod along. Why be worried by a beast not much bigger than a hoof, he seemed to say.

Then the dog darted under the very hooves of the team, to nip at Sigurd’s heels. The big animal snorted and danced sideways in his harness. ‘Easy!’ Ki called. ‘Go home, dog!’

The dog paid no mind to Ki, nor to a woman who hastened out from a sweetmeat booth to call, ‘Here, Bits! Stop that at once! What’s got into you? It’s just a horse! Leave off that!’

Around and beneath the horses the feist leaped and snapped, yapping noisily and nipping at the feathers of the huge hooves. Sigurd danced sideways, shouldering his brother, who caught his agitation. The great grey heads tossed, manes flying, fighting their bits. Pedestrians cowered back and mothers snatched up small children as the team seesawed toward the booths. Vandien had never seen the stolid beasts so agitated by such a common occurrence. Nor had he ever seen a dog so intent on its own destruction. Ki stirred the team to a trot, hoping to get out of the dog’s territory, but the feist continued to leap and snap, and the woman to run vainly behind the wagon calling for Bits.

‘I’ll pull them in and maybe she can call it off,’ Ki growled irritatedly. She drew in the reins, but Sigurd fought the restraint, tucking his head to his chest and pulling his teammate on. Vandien was silent as Ki held steady on the reins, baffled by the greys’ strange unruliness.

There was a moment when the dog seemed to be relenting. The trotting woman was almost abreast of them. Then it sprang up suddenly, to sink its teeth into Sigurd’s thick fetlock. The big grey kicked out wildly at this suddenly sharp nuisance. His next surge against the harness spooked Sigmund, and suddenly the team sprang forward. Vandien saw the slip of reins and gripped the seat. The greys had their heads and knew it. Dust rose and the wagon jounced as they broke into a ragged gallop. Vandien heard a yelp and felt a sickening jolt and the dog was no more. Behind them the woman cried out in anguish. The team surged forward as if stung. ‘Hang on!’ he warned Goat, and tried to give Ki as much space as he could. She drew firmly in on the reins, striving for control. Tendons stood out in her wrists, and her fingers were white. Vandien caught a glimpse of her pinched mouth and angry eyes. Then Goat’s face took his attention.

His sweet pink mouth was stretched wide to reveal his yellow teeth in an excited grin. His hands were fastened to the seat, but his eyes were full of excitement. He was not scared. No, he was enjoying this. The last of the huts of Keddi raced past them. Open road loomed ahead, straight and flat.

‘Let them out, Ki!’ Vandien suggested over the creak and rumble of the wagon. ‘Let them run it off!’

She didn’t look at him, but suddenly slacked the reins, and even added a shake to urge the greys on. Their legs stretched, their wide haunches rose and fell rhythmically as they stretched their necks and ran. Sweat began to stain them, soaking the dust on their coats. In the heat of the day they tired soon, and began blowing noisily even before they dropped to a trot, and then a walk. Their ears flicked back and forth, waiting for a sign. Sigmund tossed his big head, and then shook it as if he too were perplexed by his behavior. Silently Ki gathered up the reins, letting the horses feel her will. Control was hers again.

Vandien blew out a sigh of relief and leaned back. ‘What did you make of that?’ he asked Ki idly, casual now that it was over.

‘Damn dog’ was all Ki muttered.

‘Well, it’s dead now!’ Goat exclaimed with immense satisfaction. He turned to Ki, his mouth wet with excitement. ‘These horses can move, when you let them! Why must we plod along like this?’

‘Because we’ll get farther plodding like this all day than by racing the team to exhaustion and having to stop for the afternoon,’ Vandien answered. He leaned around the boy to speak to Ki. ‘Strange dog. Living right by the road like that, and barking at horses: I wonder what got into it.’

Ki shook her head. ‘She probably just got the feist. She’s just lucky it picked a steady team to yap at. Some horses would have been all over that road, people and tents notwithstanding.’

‘It’s always been a nasty dog,’ Gotheris informed them. ‘It even bit me, once, just for trying to pick it up.’

‘Then you knew it?’ Vandien asked idly.

‘Oh, yes. Melui has had Bits for a long time. Her husband gave him to her, just before he got gored by their own bull.’

Vandien turned to Ki, heedless of whether Goat read his eyes or not.

‘Want me to go back, talk to her, explain?’ he offered.

Ki sighed. ‘You’d never catch up with us on foot. And besides, what could you say besides we’re sorry it happened? Maybe she’d just as soon have someone to blame and be angry with.’ Ki rubbed her face with one hand and gave him a woeful smile. ‘What a way to start a journey.’

‘I think it’s begun rather well, myself!’ Goat announced cheerfully. ‘Now that the road’s flat and straight, can I drive? I’d like to take them for a gallop down it.’

Vandien groaned. Ki didn’t reply. Eyes fixed on the horizon, she held the sweating team to their steady plod.

‘Please!’ Goat nagged whiningly.

It was going to be a very long journey.

THREE

Ki yearned for night. She had listened to Goat nagging to drive the team for what seemed a lifetime. When he got no response to his begging, he had tried to reach over and take the reins. She had slapped his hands away with a stern ‘No!’ as if he were a great baby instead of a young man. She had seen Vandien’s tensing, and shot him a glance to warn him that she would handle this herself. But the man’s eyes had a glint of amusement in them. The damn man was enjoying her having to deal with Goat. After a long and sulky silence, Goat had proclaimed that he was bored, that this whole trip was boring, and that he wished his father could have found him some witty companions instead of a couple of mute clods. Ki had not replied. Vandien had merely smiled, a smile that made Ki’s spine cold. Handling Goat on this trip was going to be tricky; even trickier would be preventing Vandien from handling Goat. She wanted to deliver her cargo intact.

Now the sun was on the edge of the wide blue southern sky, the day had cooled to a tolerable level, and in the near distance she could see a grove of spiky trees and a spot of brighter green that meant water. Suddenly she dreaded stopping for the night. She wished she could just go on driving, day and night, until they reached Villena and unloaded the boy.

Ki glanced over at Goat. He was hunkered on the seat between her and Vandien, his bottom lip projecting, his peculiar eyes fixed on the featureless road. It was not the most scenic journey she had ever made. The hard-baked road cut its straight way through a plain dotted with brush and grazing animals. Most of the flocks were white sheep with black faces, but she had seen in the distance one herd of cattle with humped backs and wide-swept horns. The few dwellings they passed were huts of baked brick. Shepherds’ huts, she guessed, and most of them appeared deserted. A lonely land.

Earlier in the day, several caravans had passed them. Most of them were no different from the folk they had seen in Keddi, but she had noticed Vandien perk up with interest as the last line of burdened horses and Humans had passed. The folk of this caravan were subtly different from the other travellers they had seen. The people were tall and swarthy, their narrow bodies and grace reminding Ki of plainsdeer. They were dressed in loose robes of cream or white or grey. Bits of color flashed in their bright scarves that sheltered their heads from the sun, and in the bracelets that clinked on ankles and wrists. Men and women alike wore their hair long and straight, and it was every shade of brown imaginable, but all sun-streaked with gold. Many of them were barefoot. The few small children with them wore brightly colored head scarves and little else. Animals and children were adorned with small silver bells on harnesses or head scarves, so there was a sweet ringing as the caravan passed. Most of their horses plodded listlessly beneath their burdens, but at the end of the entourage came a roan stallion and three tall white mares. A very small girl sat the stallion, her dusty bare heels bouncing against his shoulders, her hair flowing free as the animal’s mane. A tall man walked at her side, but none of the animals were led, or wore a scrap of harness. The little girl grinned as she passed, teeth very white in her dark face, and Ki returned her smile. Vandien lifted a hand in greeting, and the man nodded gravely, but did not speak.

‘I bet they’ve stories to tell. Wonder where they’ll camp?’ Vandien’s dark eyes were bright with curiosity.

‘Company would be nice,’ Ki agreed, privately thinking that Goat might find boys of his own age to run with while she and Vandien made the camp and had a quiet moment or two.

‘Camp near Tamshin?’ Goat asked with disgust. ‘Don’t you know anything of those people? You’re lucky I’m here to warn you. For one thing, they smell terrible, and all are infested with fleas and lice. All their children are thieves, taking anything they can get their dirty little hands on. And it is well known that their women have a disease that they pass to men, and it makes your eyes swell shut and your mouth break out with sores. They’re filth! And it is rumored that they are the ones that supply the rebels with food and information, hoping to bring the Duke down so they may have the run of the land and take the business of honest merchants and traders.’

‘They sound almost as bad as Romni,’ Vandien observed affably.

‘The Duke has ordered his Brurjan troops to keep the Romni well away from his province. So I have never seen one, but I have heard …’

‘I was raised Romni.’ She knew Vandien had been trying to get her to see the humor of the boy’s intolerance, but it had cut too close to the bone. That conversation had died. And the afternoon had stretched on, wide and flat and sandy, the only scenery the scrub brush and grasses drying in the summer heat. A very long day …

At least the boy had been keeping quiet these last few hours. Ki sneaked another look at him. His face looked totally empty, devoid of intelligence. But for that emptiness, the face could have been, well, not handsome, but at least affable. It was only when he opened his mouth to speak, or bared those yellow teeth in his foolish grin, that Ki was repulsed. He reached up to scratch his nose, and suddenly appeared so childish that Ki was ashamed of herself. Goat was very much a child still. If he had been ten instead of fourteen, would she have expected the manners of a man, the restraint of an adult? Here was a boy, on his first journey away from home, travelling with strangers to an uncle he hadn’t seen in years. It was natural that he would be nervous and moody, swinging from sulky to overconfident. His looks were against him too, for if she had seen him in a crowd, she would have guessed his age at sixteen, or even older. Only a boy. Her heart softened toward him.

‘We’ll stop for the night at those trees ahead, Goat. Do you think that greener grass might mean a spring?’

He seemed surprised that she would speak to him, let alone ask him a question. His voice was between snotty and shy. ‘Probably. Those are Gwigi trees. They only grow near water.’

Ki refused to take offense from his tone. ‘Really? That’s good to know. Vandien and I are strangers to this part of the world. Perhaps as we travel together, you can tell us the names of the trees and plants, and what you know of them. Such knowledge is always useful.’

The boy brightened at once. His yellow teeth flashed in a grin. ‘I know all of the trees and plants around here. I can teach you about all of them. Of course, there is a lot to learn, so you probably won’t remember it all. But I’ll try to teach you.’ He paused. ‘But if I’m doing that, I don’t think I should have to help out with the chores every night.’

Ki snorted a laugh. ‘You should be a merchant, not a healer, with your bargaining. Well, I don’t think I will let you out of chores just for telling me the names of a few trees, but this first night you can just watch, instead of helping, until you learn what has to be done every night. Does that sound fair?’ Her voice was tolerant.

‘Well,’ Goat grinned, ‘I still think I shouldn’t have to do any chores. After all, my father did pay you, and I will be teaching you all these important things. I already saved you from camping near the Tamshin.’

‘We’ll see,’ Ki replied briefly, stuggling to keep her mind open toward the boy. He said such unfortunate things. It was as if no one had ever rebuked him for rudeness. Perhaps more honesty was called for. She cleared her throat.

‘Goat, I’m going to be very blunt with you. When you say rude things about the Tamshin, I find it offensive. I have never met with any people where the individuals could be judged by generalities. And I don’t like it when you nag me after I have said no to something, such as the driving earlier today. Do you think you can stop doing those things?’

Goat’s face crumpled in a pout. ‘First you start to be nice and talk to me, then all of a sudden you start saying I’m rude and making all these rules! I wish I had never come with you!’

‘Goat!’ Vandien’s voice cut in over the noise of his protest. ‘Listen. Ki didn’t say you weren’t nice. She said that some of the things you say aren’t nice. And she asked you, rather politely, to stop saying them. Now, you choose. Do you want Ki to speak honestly to you, as she would to an adult, or baby you along like an ill-tempered brat?’

There was a challenge in Vandien’s words. Ki watched Goat’s face flood with anger.

‘Well, I was being honest, too. The Tamshin are thieves; ask anyone. And my father did pay for my trip, and I don’t see why I should have to do all the work. It’s not fair.’

‘Fair or not, it’s how it is. Live with it,’ Vandien advised him shortly.

‘Maybe it seems unfair now,’ Ki said gently. ‘But as we go along, you’ll see how it works. For tonight, you don’t have to do any chores. You can just watch. And tomorrow, you may even find that you want to help.’ Her tone was reasonable.

‘But when I wanted to help today with the driving, you said no. I bet you’re going to give me all the dirty chores.’

Ki had run out of patience. She kept silent. But Vandien turned to Goat and gave him a most peculiar smile. ‘We’ll see,’ he promised.

The light was dimming, the trees loomed large, and with no sign from her the team drew the wagon from the road onto the coarse meadow that bordered it. She pulled them in near the trees. The big animals halted, and the wagon was blessedly still, the swaying halted, the creaking silenced. Ki leaned down to wrap the reins around the brake handle. She put both her hands on the small of her back and arched, taking the ache out of her spine. Vandien rolled his shoulders and started to rise from the plank seat when the boy pushed past him to jump from the wagon and run into the trees.

‘Don’t go too far!’ Ki called after him.

‘Let him run,’ Vandien suggested. ‘He’s been sitting still all day. And I’d just as soon be free of him for a while. He won’t go far. Probably just has to relieve himself.’

‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ Ki admitted. ‘You and I are used to a long day. It would be harder for the boy, especially to ask a stranger to stop the wagon for him. Maybe we should make a point of stopping a few times tomorrow. To eat, and to rest the horses.’

‘Whatever you think.’ Vandien dropped lightly to the ground. He stood stretching and rolling his shoulders. ‘But I don’t think that boy would be embarrassed to say anything.’ He glanced over at Ki. ‘And I don’t think your coaxing and patience will get anywhere with him. He acts like he’s never had to be responsible for his own acts. Sometime during this trip, he’s going to discover consequences.’

‘He’s just a boy, regardless of his size. You’ve realized that as much as I have.’ Ki groaned at her stiffness as she climbed down from the driving seat.

‘He’s a spoiled infant,’ Vandien said agreeably. ‘And I almost think it might be easier to humor him as such for this trip, instead of trying to grow him up along the way. Let his uncle worry about teaching him manners and discipline.’

‘Perhaps,’ Ki conceded as her fingers worked at the heavy harness buckles. On his side of the team, Sigurd gave his habitual kick in Vandien’s direction. Vandien sidestepped with the grace of long habit, and delivered the routine slap to the big horse’s haunch. This ceremony out of the way, the unharnessing proceeded smoothly.

As they led the big horses out of the traces and toward the water, Ki wondered aloud, ‘Where’s Goat gotten to now?’

A loud splashing answered her. She pushed hastily through the thick brush surrounding the spring. The spring was in a hollow, its bank built up by the tall grasses and bushes that throve on its moisture. Goat sat in the middle of the small spring, the water up to his chest. His discarded garments littered the bank. He grinned up at them. ‘Not a very big pool, but big enough to cool off in.’

‘You did get yourself a cool drink before stirring up the mud on the bottom, didn’t you?’ Vandien asked with heavy sarcasm.

‘Of course. It wasn’t very cold, but it was drinkable.’

‘Was it?’ Vandien asked drily. He glanced over at Ki, then reached to put Sigurd’s lead into her hands. ‘You explain it to the horses,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure they’d believe me.’ He turned and strode back through the trees to the wagon. Ki was left staring down at Goat. She forced herself to behave calmly. He had not been raised by the Romni. He could know nothing of the fastidious separation of water for drinking from water for bathing. He would know nothing of fetching first the water for the wagon, then watering the horses, and then bathing. Not only had he dirtied all the available water, his nakedness before her was offensive. Ki reminded herself that she was not among the Romni, that in her travels she had learned a tolerance for the strange ways of other folk. She reminded herself that she intended to be patient, but honest, with Goat. Even if it meant explaining these most obvious things.

He grinned at her and kicked his feet, stirring up streamers of mud. Sigurd and Sigmund, thirsty and not fussy, pulled free of her slack grip and went to the water. Their big muzzles dipped, making rings, and then they were sucking in long draughts. Ki wished she shared their indifference.

Goat ignored them. He smiled up at Ki. ‘Why don’t you take your clothes off and come into the water?’ he asked invitingly.

He was such a combination of offensive lewdness and juvenility that Ki couldn’t decide whether to glare or laugh. She set her features firmly in indifference. ‘Get out of there and get dressed. I want to talk to you.’ She spoke in a normal voice.

‘Why can’t we talk in here?’ he pressed. He smiled widely. ‘We don’t even have to talk,’ he added in a confidential tone.

‘If you were a man,’ she said evenly, ‘I’d feel angry. But you’re only an ill-mannered little boy.’ She turned her back on him and strode away, trying to contain the fury that roiled through her.

‘Ki!’ His voice followed her. ‘Wait! Please!’

The change in his tone was so abrupt that she had to turn to it. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said softly, staring at her boots. His shoulders were bowed in toward his hairless chest. When he looked up at her, his eyes were very wide. ‘I do everything wrong, don’t I?’

She didn’t know what to say. The sudden vulnerability after all his boasting was too startling. She couldn’t quite believe it.

‘I just … I want to be like other people. To talk like they do, and be friends.’ The words were tumbling out of him. Ki couldn’t look away. ‘To make jokes and tease. But when I say it, it doesn’t come out funny. No one laughs, everyone gets mad at me. And then I … I’m sorry for what I said just now.’

Ki stood still, thinking. She thought she had a glimpse of the boy’s misunderstanding. ‘I understand. But those kinds of jokes take time. They’re not funny from a stranger.’

‘I’m always the stranger. Strange Goat, with the yellow eyes and teeth.’ Bitterness filled his voice. ‘Vandien already hates me. He won’t change his mind. No one ever gives me a second chance. And I never get it right the first time.’

‘Maybe you don’t give other people a second chance,’ Ki said bluntly. ‘You’ve already decided Vandien won’t like you. Why don’t you change the way you behave? Try being polite and helpful. Maybe by the end of this trip, he’ll forget how you first behaved.’

Goat looked up at her. She didn’t know if his gaze was sly or shy. ‘Do you like me?’

‘I don’t know yet,’ she said coolly. Then, in a kinder voice, she added, ‘Why don’t you get dried off and dressed and come back to camp? Try being likeable and see what happens.’

He looked down at the muddied water and nodded silently. She turned away from him. Let him think for a while. She took the leads from the horses and left them to graze by the spring. They wouldn’t stray; the wagon was all the home they knew. As she pushed through the brush surrounding the spring, she wondered if she should ask Vandien to talk to the boy. Vandien was so good with people, he made friends so effortlessly. Could he understand Goat’s awkwardness? The boy needed a friend, a man who accepted him. His father had seemed a good man, but there were things a boy didn’t learn from his father. She paused a few moments at the edge of the trees to find words, and found herself looking at Vandien.

He knelt on one knee, his back to her, kindling the night’s fire. The quilts were spread on the grass nearby; the kettle waited beside them. As she stepped soundlessly closer, she saw that his dark hair was dense and curly with moisture. He had washed already, yes, and drawn a basin of water for her as well, from the water casks strapped to the side of the wagon. Sparks jumped between his hands; grass smouldered and went out. He muttered what was probably a curse in a language she didn’t know. She stepped closer, put one hand on his shoulder and stooped to kiss the nape of his neck. He almost flinched, but not quite.

‘I knew you were there,’ he said matter-of-factly, striking another shower of sparks. This time the tinder caught and a tiny pale flame leaped up.