Полная версия

Franco

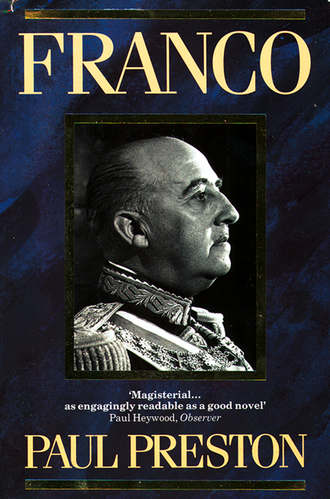

The Dictatorship was also a period in which Franco experienced further inflation of his ego. On the evening of 3 February 1926, his fellow cadets of the fourteenth intake (promoción no. 14) at the Academia de Infantería de Toledo met to pay homage to the first of their number to become a general. They presented him with a dress sword and a parchment with the following inscription: ‘When the passage through the world of the present generation is no more than a brief comment in the book of History, there will endure the memory of the sublime epic written by the Spanish Army in the development of the nation. And the glorious names of the most important caudillos will be raised on high, and above them all will be lifted triumphantly that of General Francisco Franco Bahamonde to reach the sublime heights achieved by other illustrious men of war, Leiva, Mondragón, Valdivia and Hernán Cortés. His comrades pay this tribute of admiration and affection to him in recognition of his patriotism, his intelligence and his bravery’.56

In the course of the next few days, Franco would receive many telegrams from the local authorities of El Ferrol recounting the acts of homage mounted for his mother. On Sunday 7 February, bands played, firework displays were organized and ships in the bay sounded their horns. The town turned out to acclaim the historic flight by Ramón, who was still in Argentina, although Franco was not forgotten in the endless tributes made to Doña Pilar Bahamonde y Pardo de Andrade. 12 February was declared a holiday in El Ferrol in honour of both brothers. The streets of the town were illuminated and a Te Deum was sung in the Church of San Julián to celebrate their achievements. The plaque was unveiled in the calle María. Messages of congratulation to Doña Pilar for both her sons arrived from the Alcaldes (mayors) of El Ferrol, the four provincial capitals of Galicia and from many towns across Spain.57 On 10 February, a massive crowd turned out in the Plaza de Colón (Columbus) in Madrid to acclaim Ramón’s achievement. In part, the media coverage and public enthusiasm were orchestrated by the Primo de Rivera dictatorship in order to profit in propaganda terms from the flight of the Plus Ultra.

The adulation was largely directed at Ramón, but there is no reason to believe that Franco was resentful at seeing the black sheep of the family suddenly converted into a national hero. The adulation of his brother as a twentieth century Christopher Columbus may, however, have inspired Franco’s later efforts to present himself as a modern-day El Cid. Franco always had an intense loyalty to his family and, over the years, was to use his own position to help and protect Ramón from the consequences of his wilder actions. In any case, his own triumphs and popularity were sufficient in frequency and intensity for him not to need to feel envy. At Easter 1926, during the Corpus Christi procession at Madrid’s San Jerónimo Church, he commanded the troops which lined the streets and escorted the host. As the legendary hero of Africa, he was the object of the admiring attention of the upper class Madrileños who made up the congregation.58 In the late summer of 1927, Franco accompanied the King and Queen on an official visit to Africa during which new colours were given to the Legion at their headquarters in Dar Riffien.59

On 14 September 1926, Franco’s first and only child María del Carmen was born in Oviedo where Carmen had gone to be with her dying father.60 The new arrival was to become the focus of his emotional life. Years later, he was to say ‘when Carmen was born, I thought that I would go mad with joy. I would have liked to have had more children but it was not to be’.61 There have been insistent rumours that Carmen was not really Francisco’s daughter but was adopted, and that the father may have been his promiscuous brother Ramón. There is no evidence to support this theory, which seems to have arisen entirely from the fact that there are no known photographs of Carmen Polo noticeably pregnant and from Ramón’s notorious sexual adventurism.62 Franco’s sister, Pilar, went out of her way in her memoirs to make a point of saying that she saw Carmen Polo pregnant although her dates are wrong by two years.63

The posting to Madrid began a period in which Franco had plenty of spare time. Rather than make the lives of his colonels a misery by frequent surprise inspections, he left them to get on with running their own barracks, a pattern that he would later follow with his ministers. He rented an apartment on the elegant Castellana avenue and enjoyed a busy social life. He regularly met military friends from Africa and the Toledo Academy at the regular social gatherings or tertulias of the upper-class club, La Gran Peña, and in the cafés of Alcalá and the Gran Via. He was relatively close to Millán Astray, Emilio Mola, Luis Orgaz, José Enrique Varela and Juan Yagüe.64 While living in Madrid, he acquired a passion for cinema and became a member of the tertulia of the politician and writer Natalio Rivas, a member of the Liberal Party.65 At Rivas’s invitation, he appeared along with Millán Astray in a film entitled La Malcasada made by the director Gómez Hidalgo in Rivas’s house. Franco’s small part was as an Army officer recently returned from the African wars.66

At this stage of his life, as later, Franco had little interest in day-to-day politics. None the less, he began to think that ultimately he might play a political role of some kind. The popular acclaim which he had received after Alhucemas, the rapidity of his promotions, and the company which he now kept in Madrid, all pushed him to take for granted his own importance as a national figure. As he put it in retrospect ‘I was, as a result of my age and my prestige, called to render the highest services to the nation’. The Army’s apparent political success under Primo de Rivera may also have increased his tendency to dream of higher things for himself. He claimed later that, in preparation for his transcendental tasks, and taking advantage of the fact that his command in Madrid left him with very little to do, he began to read books on contemporary Spanish history and political economy.67 How much reading he did is impossible to say; his books were lost in Madrid in 1936 when his flat was ransacked by anarchists. Certainly, neither his speeches nor his own writings indicate any significant insight into history or economics.

Given his propensity to chat, he probably talked rather than read about economics. As he claimed later, he started at this time ‘with some frequency to visit the manager of the Banco de Bilbao, where Carmen had a few savings (unos ahorrillos)’. The banker in question was affable and intelligent and stimulated in Franco an interest in economics. Franco also discussed contemporary political issues with his immediate circle of friends and acquaintances. It is likely that such café conversations with friends, the bulk of whom were Africanistas like himself, can only have cemented his prejudices. Nevertheless, in later life he was to place enormous value on these conversations.68

His reading and his tertulias boosted Franco’s confidence in his own opinions to an inordinate degree. While on holiday in Gijón in 1929, he bumped into General Primo de Rivera on the beach. The ministers of Primo’s government were spending a few days together away from Madrid and the Dictator invited Franco to lunch with them – a mark of considerable favour by Primo towards the young general. His self-esteem duly inflated, Franco found himself seated next to José Calvo Sotelo, the brilliant Finance Minister, who was in the midst of trying to defend the value of the peseta against the consequences of a massive balance of payments deficit, a bad harvest and the first signs of the great Depression. Franco assured an intensely irritated Calvo Sotelo that there was no point in using Spain’s gold and foreign currency reserves to support the value of the peseta and that the money so used would be better spent on industrial investment. The reasoning by which Franco reached the interpretation he put before the Minister revealed a simple cunning: he based his argument on the belief that there need be no link between the exchange rate of a currency and the nation’s gold and foreign reserves provided their value were kept secret.69

The economic difficulties discussed at this lunch were not the only problems besetting the Dictatorship. The military was deeply divided and some sections of the Army were turning against the regime. Franco was paradoxically to be the beneficiary of one of the most serious errors made by the Dictator in this regard. Primo de Rivera was anxious to reform the antiquated structures of the Spanish Army and in particular to slim down the inflated officer corps. His ideal was a small professional Army but, as a result of the reversal of his original policy of abandonismo in Morocco, it had grown significantly in size and cost in the mid-1920s. By 1930, the officer corps would be reduced in size by only about 10 per cent and the Army as a whole by more than 25 per cent, at an inordinately high price in terms of internal military discontent. Large sums were spent on efforts at modernization although the final increase in the number of mechanized units was immensely disappointing.70

The relative failure of Primo’s technical reforms was overshadowed by the legacy of one bitterly divisive issue. Most publicity was generated, and most damage caused in terms of morale, by the Dictator’s efforts to eradicate the divisions between the artillery and the infantry over promotions. To a large extent, this was the question which had given birth to the Juntas de Defensa in 1917. Divisions between the infantry, and particularly the Africanistas, on the one hand, and the artillery and the engineers on the other arose from the fact that it was much more difficult for an engineer or the commander of an artillery battery to gain promotion by merit than for an infantry officer leading charges against the Moors. To underline their discontent with a promotion system which favoured the colonial infantry, the Artillery corps had sworn in 1901 to accept no promotions which were not granted on grounds of strict seniority and to seek instead other rewards or decorations.

Although on coming to power Primo de Rivera had been thought within the Army to be more sympathetic to the artillery position, he seems to have changed his mind as a result of his contacts with the infantry officer corps in Morocco before and during the Alhucemas operation.71 By decrees of 21 October 1925 and 30 January 1926, he introduced greater flexibility into the promotion system. This gave him the freedom to promote brave or capable officers but it was also perceived as opening a Pandora’s box of favouritism. There was already tension when, in a typically precipitate manner, on 9 June 1926, the Dictator issued a decree specifically obliging the artillery to accept the principle of promotions by merit. Those who had accepted medals instead of promotions were now deemed retrospectively to have been promoted. Hostility within the mainland officer corps to a whole range of tactless encroachments on military sensibilities by the Dictator was already leading to contacts between some officers and the liberal opposition to the regime. It came to a head in a feeble attempt at a coup known as the Sanjuanada on 24 June 1926.72 In August, the imposition of promotions upon the artillery provoked a near mutiny by artillery officers who confined themselves to their barracks. In Pamplona, shots were fired by infantrymen sent to put an end to one such ‘strike’ of artillerymen. The Director of the Artillery Academy of Segovia was sentenced to death, a sentence later commuted to life imprisonment, for refusing to hand over the Academy.73 Throughout the issue, Franco was careful not to get involved. He, more than anyone in the entire armed forces, had reason to be grateful to the system of promotions by merit.

Primo de Rivera won, but at the cost of dividing the Army and of undermining its loyalty to the King. His policy on promotions was to provide much of the cause for the grievances which lay behind some officers moving in the direction of the Republican movement. Thus, when the time came, some sectors of the Army would be ready to stand aside and permit first Primo’s own demise and then the coming of the Second Republic in April 1931.74 Broadly speaking, the Africanistas remained committed to the Dictatorship and thereafter were to be bitterly hostile to the democratic Republic which followed it in 1931.75 Indeed, the fault lines of the divisions created in the 1920s would run right through to the Civil War in 1936. Many of those who moved into opposition against Primo would be favoured by the subsequent Republican regime. In contrast, the Africanistas, including Franco, would see their previously privileged position dismantled.

The artillery/infantry, juntero/Africanista, issue had an immediate and direct impact on Franco’s life. In 1926, the Dictator was convinced that part of the promotions problem derived from the fact that there were separate academies for the officers of the four major corps, the infantry in Toledo, the artillery in Segovia, the cavalry in Valladolid and the engineers in Guadalajara. He concluded that Spain needed a single General Military Academy and decided to revive the Academia General Militar which had existed briefly during its so-called ‘first epoch’ between 1882 and 1893.76 By this time, and particularly after Alhucemas, Primo had developed a great liking for Franco. He told Calvo Sotelo that Franco was ‘a formidable chap, and he has an enormous future not only because of his purely military abilities but also because of his intellectual ones’.77 The Dictator was clearly grooming Franco for an important post. He sent him to the École Militaire de St Cyr, then directed by Philippe Pétain, in order to examine its structure. On 20 February 1927, Alfonso XIII approved a plan for a similar Spanish academy, and on 14 March 1927 Franco was made a member of a commission to prepare the way for it. By Royal Decree of 4 January 1928, he was appointed its first director. He expressed a preference for it to be sited at El Escorial but the Dictator insisted that it be in Zaragoza. Years later, Franco was alleged to have said that, if the Academy had been located at El Escorial instead of 350 kilometres from the capital, the fall of the monarchy in 1931 could have been avoided.78

In moving to the Academia General Militar, Franco was leaving behind him the kind of soldiering in which he made his reputation. Never again would he lead units of assault troops in the field. It was a major change, which taken with his marriage in 1923 and the birth of his daughter in 1926, would affect him profoundly. Until 1926, Franco was an heroic field soldier, an outstanding column commander, fearless if not reckless. Henceforth, as befitted his changing sense of his public persona, he would take ever fewer risks. In Morocco, he had been a ruthless disciplinarian, an abstemious and isolated individual with few friends.79 After his return to the Peninsula, he seems to have relaxed slightly, although he was always to remain obsessed with the primacy of unquestioning obedience and discipline. He became readier to turn a blind eye to laziness or incompetence in his subordinates, getting the best out of willing collaborators by manipulation and rewards. He became a relatively convivial frequenter of clubs and cafés where he would take an aperitif and give rein to his inclination to chat, recounting anecdotes and reminiscences among a group of military friends.80

Until the late 1920s, he showed few signs of being the archetypal gallego, slow, cunning and opaque, of his later years. He was a man of action, obsessed with his military career and little else. His early military writings are relatively straightforward and decently written, with some sensitivity to people and places. He was, of course, reserved, and predisposed by his military experience, and particularly by Africa, to certain political ideas, hostile to the Left and to regional autonomy movements. If he did read about politics, economics and recent history, it was probably more to confirm his prejudices than in search of enlightenment. From this time, a convoluted style and a pomposity of tone begins to be discernible in his speeches. In part, family responsibilities account for a greater caution but the more potent motive for his self-regard was a perception of his potential political importance. He was the object of public adulation in certain circles and had had plenty of indications that he was the general with the most brilliant prospects.81 He was showered with promotions, honours and plum postings. The talk of his being the youngest general in Europe cannot have failed to have affected him, as must the idea of providence watching over him, an idea particularly dear to his wife. To her influence in this respect must be added that of his near inseparable cousin, Pacón, now a major, who had become his ADC in the late summer of 1926.82

At the end of May 1929 there appeared in the magazine Estampa, in the section called ‘The woman in the home of famous men’, a rare interview with Carmen Polo and her husband. Conducted by Luis Franco de Espés, the Barón de Mora, a fervent admirer of Franco, the interview was as much concerned with ‘the famous man’ as with ‘the woman in the home’. Asked if he was satisfied to be what he was, Franco replied sententiously ‘I am satisfied to have served my fatherland to the full’. The Barón asked him what he would have liked to be if not a soldier to which he replied ‘architect or naval officer. However, aged fourteen I entered the Infantry Academy in Toledo against the will of my father.’ This was the first time that Franco had indicated any paternal opposition to his joining the military academy. There is no reason why his father should have opposed the move and, if he had done, there can be little doubt that he would have imposed his will. Apparently, Franco was trying to put distance between his beloved military career and his hated father.

‘All this’, he said, ‘is only with regard to my profession because my real inclination has always been towards painting’. On lamenting that he had no time to practice any particular genre, Carmen interrupted to point out that he painted rag dolls for their daughter, ‘Nenuca’. Then, the interview turned to the ‘the beautiful companion of the general, hiding the supreme delicacy of her figure behind a subtle dress of black crêpe’. Blushing, she recounted how she and her husband had fallen in love at a romería (country fair) and how he had pursued her doggedly thereafter. Playing the role of the faithful hand-maiden to the great man, she revealed her husband’s major defects to be that ‘he likes Africa too much and he studies books which I don’t understand’. Turning back to Franco, the Barón de Mora asked him about the three greatest moments of his life to which he responded with ‘the day that the Spanish Army landed at Alhucemas, the moment of reading that Ramón had reached Pernambuco and the day we got married’. The fact that the birth of his daughter Carmen did not figure in the list suggests that he was more anxious to project an image of patriotism untrammelled by ‘unmanly’ emotions. He was then asked about his greatest ambition which he revealed as being ‘that Spain should become as great again as she was once before.’ Asked if he was political, Franco replied firmly ‘I am a soldier’ and declared that his most fervent desire was ‘to pass unnoticed. I am very grateful for certain demonstrations of popularity but you can imagine how annoying it is to feel that you’re often being looked at and talked about’. Carmen listed her greatest love as music and her greatest dislike as ‘the Moors’. She had few happy memories of her time as an Army wife in Morocco spent consoling widows.83

Franco had arrived in Zaragoza on 1 December 1927 to supervise the building and installation of the new institution. The first entrance examinations were held in June 1928. On 5 October of that year, with the new buildings still unfinished, the Academy opened for its first intake in a nearby barracks. The new Director’s speech on opening the Academy reflected the philosophy that he had learned from his mother. Its theme was ‘he who suffers overcomes’.84 He also instructed the cadets to follow the ‘ten commandments’ or ‘decálogo’ which he had compiled on the basis of a similar ‘decálogo’ elaborated for the Legion by Millán Astray. Expressed in the most sententious terms, the commandments were: 1) Make great love for the Fatherland and fidelity to the King manifest in every act of your life; 2) Let a great military spirit be reflected in your vocation and your discipline; 3) Link to your pure chivalry a constant jealous concern for your reputation; 4) Be faithful in the fulfilment of your duties, being scrupulous in everything that you do; 5) Never grumble, nor tolerate others doing so; 6) Make yourself loved by those of lower rank and highly regarded by your superiors; 7) Volunteer for every sacrifice at times of greatest risk and difficulty; 8) Feel a noble comradeship, sacrificing yourself for your comrades and taking delight in their successes, prizes and progress; 9) Love responsibility and be decisive; 10) Be brave and self-denying.85

The generation educated under Franco’s close supervision at the Academia General Militar de Zaragoza, in its so-called second epoch between 1928 and 1931, was to receive significantly more practical training than had hitherto been the practice in the Toledo infantry academy. Franco insisted that no textbooks be used and that all classes be based on the practical experiences of the instructors.86 Skill in the use and care of weapons was insisted upon. The horsemanship of the graduates was of a high standard. Franco himself would direct from horseback the toughest manoeuvres. However, the central stress, derived from the decálogo, was on ‘moral’ values: patriotism, loyalty to the King, military discipline, sacrifice, bravery.87 The idea that ‘moral’ values could triumph over superior numbers or technology was one of the constant refrains of Franco’s military thought. Reflecting the Director’s own experiences in the primitive Moroccan war, the level of tactical and technological education at Zaragoza was not highly advanced and considerable effort went into denouncing democratic politics.

During the Civil War, officers who had trained at the Academy under Franco remembered him as a martinet who had laid traps for unwary cadets. In the streets of Zaragoza, he would pretend to be looking in shop windows to catch those who tried to get past without saluting their Director. As they went on, they would be called back by Franco’s soft, high, feared, voice. Remembering the nightly activities of his own contemporaries at Toledo, he insisted that all cadets carry at least one condom while walking in the city. Occasionally, he would stop them in the street and demand to see their protective equipment. There were strict penalties for those unable to produce it.88 In his farewell speech to the Academy in 1931, he listed among the great patriotic achievements of his time in the post the elimination of venereal disease among the cadets through ‘vigilance and prophylaxis’.89 His pride in that achievement was reflected when, in 1936, he boasted to his English teacher that he had ‘put down vice ruthlessly’ among the cadets at Zaragoza.*90

Franco’s period at the Academy was viewed in retrospect as a triumph by Africanistas and other right-wing Army officers and a disaster by liberal and left-wing officers. His brother Ramón wrote to him to complain of the ‘troglodytic education’ imparted there. For the distinguished Africanista, General Emilio Mola, in contrast, it was the peak of excellence.91 The Academy’s regulations demanded that the teaching staff be chosen on the basis of méritos de guerra, irrespective of the subject being taught. Accordingly, the teaching staff was dominated by Africanista friends of Franco, most of whom had been brutalized by their experiences in a pitiless colonial war and were noted more for their ideological rigidity than for their intellectual attainments. Of 79 teachers, 34 were infantrymen and 11 from the Legion. The assistant director of the Academy was Colonel Miguel Campins, a good friend and comrade in arms from Africa who had been with him at the battle of Alhucemas. A highly competent professional, Campins elaborated the training programme at the Academy.92 The other senior members of staff included Emilio Esteban-Infantes, later to be involved in the attempted Sanjurjo coup of 1932; Bartolomé Barba-Hernández, who was to be, on the eve of the Civil War, leader of the conspiratorial organization Unión Militar Española; and Franco’s lifelong close friend Camilo Alonso Vega, later to be a dour Minister of the Interior. Virtually without exception, the Academy’s teachers were to play prominent roles in the military uprising of 1936. With such men on the staff, the Academy concentrated on inculcating the ruthless arrogance of the Foreign Legion, the idea that the Army was the supreme arbiter of the nation’s political destiny and a sense of discipline and blind obedience. A high proportion of the officers who passed through the Academy were later to be involved in the Falange. An even higher proportion fought on the Nationalist side during the Civil War.93