Полная версия

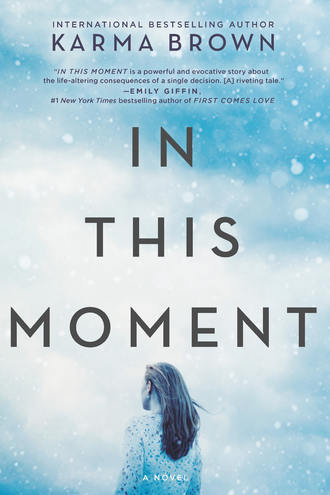

In This Moment

Then I hear someone say, “Oh, my God, his leg,” and I pull my eyes down from Jack’s head, and for the first time I look at Jack’s left leg. His shorts have shifted up, so there’s nothing obscuring the injury. But despite the clear view I can’t make sense of what I’m seeing.

Because nothing is where it should be. Most noticeable is Jack’s foot, pointing in the wrong direction—facing inward the way Audrey used to draw the shoes on her stick figures when she was in preschool. The leg also seems crooked where there isn’t a joint, a few inches above his ankle, and I feel bile rise in my throat when I realize what the thing sticking out of his shin is: a jagged piece of bone. “I think I can see his bone,” I whisper to the operator, my voice catching. “It’s...it’s coming out of his leg.” The man looks at me, pale, clearly unsure what to do, while Emma murmurs, “Compound fracture to the tibia.”

“Should we do anything with his leg?” the man asks quietly, looking from me to Emma, hands still levitating above Jack’s mangled leg.

“She said to leave the leg,” I tell the man, who nods—a look of relief passing across his face. “The ambulance is almost here.” Moments later we hear the sirens, and it’s as though the three of us take a collective deep breath. Help is almost here, and soon it won’t be up to us to hold the pieces of this poor young man together.

Someone comes up beside me, brushing against my arm. Audrey. “I called Sam,” she says, her voice quiet and close to my ear—the one without the phone. “He and his dad will be here soon.” My heart lurches at the thought of getting that phone call. Of the crushing panic of hearing a car has hit your child.

“I want to help,” she whispers. “What can I do?” Her tear-streaked face is still a concerning shade of gray, but there’s a firm set to her mouth I know well. It’s the face she gets when she’s determined to have her way, and is similar to the face Ryan made this morning when we argued. I want to tell her to go back to the car, to not look too closely at Jack, but I know there’s no point now.

I shift the mouthpiece of the phone away and whisper back to her. “Talk to him, honey. Can you do that? Just don’t touch him, okay? We need to keep him still.” With a nod she kneels on the ground beside Jack’s head, beside Emma. Watching her, I vow to put up the gel clings the moment we get home and to bury the bird under the hydrangeas.

“I can see the ambulance,” I tell the operator, who in her fluid, calming voice, tells me we’ve done a great job, the paramedics are almost here, but don’t hang up yet. Just then a police officer approaches and starts pressing the crowd back, repeating in a loud and authoritative voice, “Give us some room, folks,” to make space for the incoming ambulance.

I scan the faces nearby, looking to see if Andrew Beckett has arrived. It’s then that I see her—the woman who drove her car right into Jack—sitting on the curb beside the white Volvo wagon with a massive dent in its hood, a blood-spattered air bag hanging out its open driver’s side window, the windshield smashed in a spiderweb-like circle, like a basketball—or someone’s head—hit it.

A shiver moves through me when I realize I know this woman. It’s Sarah Dunn, Audrey’s history teacher. She’s staring straight ahead, at Jack’s skateboard—which is upside down and trapped under her front wheel—her face slack and mouth hanging open. She’s bleeding from her forehead, with two red rivers streaming out of her nose, but she seems unaware of her injuries. There are two more officers standing beside her, one peering inside the Volvo and the other talking into the walkie-talkie attached to his shoulder, but both ignoring her. I wonder how the hell she didn’t see Jack, and it’s then she glances up and our eyes meet.

Maybe it’s my own guilt rising up through the wall of shock, but it’s as though she knows I was driving the other car. That I was the one who deemed it a safe crossing for this innocent and clearly vulnerable teenager, now lying in the road with an injury that will forever change his life. Maybe even—I realize with a sickening lurch in my stomach—end it.

How did you not see me coming? I can almost hear her saying. How could you let him cross the street?

Why were you driving so fast in the school zone? I would shout back, not understanding how she wouldn’t know better and feeling defensive for my part in this accident.

But she wouldn’t answer my question, would only say one thing in this dreamlike conversation I have with her. We did this, Meg, is what she would say if she weren’t catatonic on the curb.

My eyes drop back to Jack, now surrounded by paramedics moving quickly and quietly, like they’ve rehearsed this exact scenario a hundred times. The half-naked man, shivering under the ill-fitting trench coat, takes his phone gently from my hand, and Emma wraps her arms around Charlotte, who has tears running down her face, and when I look back up, Sarah isn’t sitting on the curb anymore.

We did this.

I’m suddenly slammed with a memory from when I was sixteen; from a terrible night where another teenager lay bleeding and broken on a road in front of me. I have worked hard not to think about that night anymore, because I can’t breathe around my guilt when I do. But just like that, it’s back, and I’m left sucking in air around the heaviness of the memory, a fish out of water.

And like the part I played in that night when I was sixteen, I am the reason Jack Beckett crossed the road when he did. It’s my fault, I think, as the ambulance pulls out, sirens blaring. With a simple, careless wave of my hand, I did this.

5

The police have taped off the area and asked me to stay put until they can take statements, which they’re currently doing with Emma and the man who has now replaced the bloodied trench coat with a sweatshirt that fits much better. I’m sitting in my SUV, restless and still trembling even with my coat on, trying to bring life back into my fingers while also trying to reach Ryan for the tenth time, when Audrey tells me Sam and his dad are here. Before I can respond she opens the car door and jumps out, running toward them.

A shiver runs through me when I look at Sam, so much like Jack in every way it’s disconcerting—for a moment my shock-weary mind tries to believe he is Jack, just fine and home from school as though nothing has happened. That this afternoon’s accident was merely a fever-fueled nightmare brought on by whatever virus has infiltrated my body.

I see Andrew, tall and lean-limbed like his boys, some thickness around his middle only visible because the wind today is strong, molding his shirt to his stomach. He’s standing slightly behind Sam, who is hugging Audrey so tight she looks as though she might disappear into his body, and staring at the road where Jack was lying only minutes before. His eyes are trained on the pool of blood, now littered with medical supplies the paramedics left in their hasty departure. He stumbles back slightly, a hand going to his open mouth. Audrey and Sam are lost together, not noticing Andrew’s stumble, and I step closer to him, concerned.

“Andrew,” I say, putting my hand on his arm. We’ve been friendly with one another since I sold them their house, more so now that our kids are dating, and have had our fair share of backyard barbecue conversations over the last few years. But even still, Ryan and I don’t count the Becketts as close friends. I suddenly wish there was someone else here, someone he knows better than me—the last thing you want is to get this kind of news from the person who knows how you like your hamburger cooked and what your home-buying budget is, but not much beyond that.

He looks at my hand on his arm, my SUV that I just got out of, and finally at my face. “Did you hit him?” he asks, the words tumbling from his lips desperate, quiet, laced with anguish.

“No,” I say, shaking my head a bit wildly. Then, with more conviction I add, “No. It wasn’t me. We were on the other side of the road.” I say nothing about waving Jack across the street. “They just took him, in the ambulance. To Children’s.” I’m about to offer to drive him to the hospital and then remember I can’t leave the scene. “The police have asked me to stay. Can you drive yourself to the hospital? Andrew?” Watching him, I know that’s not a good idea. “Or maybe the police can take you?”

He’s no longer looking at me, or the road. I follow his gaze and see Sarah in the back of a police cruiser parked a few feet away, her head down and long, dark curls framing her face. “Is that who hit my son?” he asks, so quietly I lean closer to hear him better. But he doesn’t say anything else, so I simply nod. “Yes,” I reply. “It’s Sarah Dunn.”

“Sarah Dunn,” he repeats, his voice monotone, his eyes unblinking as he stares at Sarah inside the car. “Jack’s history teacher.” He makes a strange sound in the back of his throat, and with some alarm I notice how unwell he looks. “How? Why?”

“I don’t know exactly what happened, Andrew. I don’t know how she didn’t—” I’m about to say, “see him,” but I hold my words, because I can tell he can’t take any more in right now. He’s operating on autopilot, and precariously close to losing it. “I don’t know exactly what happened,” I repeat. “Her car wasn’t there one moment and then the next...”

I glance toward the cruiser and Sarah, where his gaze continues to rest. “I still have to talk with the police,” I say, trying to fill the silence.

His face has lost what little color it had when he arrived, and he’s shaking head to toe. “Andrew?” Even though he’s much taller, wider than me, I put an arm around him as best I can. “Do you want to sit down?” I wonder if he’s going to collapse and how I’ll keep him from crashing to the ground if he does. I move my feet slightly farther apart, as far as my dress allows, so I have better balance. But he doesn’t fall. Instead he turns to me, his back to the scene, and says, “I have to go.” His eyes are unfocused, and it’s clear he should not be getting behind the wheel. Just then Emma hurries up to us, holding Charlotte’s hand tightly as they cross the road, the way she used to when Charlotte was much younger. Though another day I might scoff at her overprotectiveness, I don’t blame her for it after what just happened.

“Andrew. I’m going to drive you and Sam to the hospital. Give me your keys.” Emma’s tone is no-nonsense and urgent, and Andrew hands her his key chain without a word. Then she says, “Sam, take your dad back to the car. We’re right behind you.” She turns to me. “The police are ready to talk with you now, Meg,” she says, before she and Charlotte break into a run, heading to Andrew’s car.

“Mom, I want to go with Sam,” Audrey cries, tugging on my arm, her eyes on Andrew’s car a half block away. “Mom, they’re leaving. Please!” I see Emma get in the driver’s side of Andrew’s car, and the car takes off quickly toward the hospital.

I shake my head. “You’re staying with me.”

She makes a sound that’s partway between a sob and an angry, frustrated groan, and I go to rub her back, but she pulls away so my hand only finds air. “After I talk with the police we’ll drive to the hospital. Promise. Okay?”

Her lips are pressed tightly together, eyes red-rimmed, and for a moment I think she might scream at me. But then she launches herself into my arms, and I hold her petite, shaking body and whisper that everything will be all right, praying it’s the truth.

* * *

The police take my statement—no, I didn’t notice anything strange about Ms. Dunn’s car or her driving or that she was on her phone. I didn’t even see her car until it was too late. Yes, I did wave Jack Beckett across the street in a nonpedestrian crossing zone. Yes, I thought it was safe for him to cross, because I didn’t see the other car coming, like I already told you—and then they let me go. I’m grateful the drive to the hospital is a short one because I’m so bone-weary I probably shouldn’t be driving.

We park in the visitors’ lot and make our way into the hospital. There’s an email from Emma, which this time I don’t delete—Jack is being evaluated, and she and Charlotte are with Sam and Andrew in the emergency waiting room.

It’s surprisingly busy for late afternoon on a Monday, the waiting room littered with worried parents and kids holding kidney-shaped pans under their chins, ice packs pressed to foreheads, and arms held stiffly in makeshift slings. I see Emma on the other side of the room, and we hurry over. Sam and Charlotte are sitting side by side, a few seats down from Emma, both staring at their phone screens. I don’t see Andrew.

“Sam,” Audrey says, and at the sound of her voice he looks up. Charlotte moves over one seat so Audrey can sit beside Sam, who leans heavily against her. She takes the weight of him and grabs his hand, and I smile gently when she catches my eye. I sit down beside Emma. “What’s happening?”

“I don’t know,” she replies. “Andrew is with Jack, and Alysse is trying to get on a plane. She’s in New York City and isn’t supposed to be home until late tomorrow night.” Emma shakes her head. “I can’t even imagine, being a plane ride away when this is happening to your child.” I swallow hard, feeling my head spin a little.

“Are you all right?” Emma asks, before shaking her head and letting her breath out slowly. “Of course not. How could any of us be okay?”

For a moment I wish things between us were the way it used to be. Back when Emma knew the day-to-day nuances of my life better than even Ryan did, and would have known exactly what to say to make things better. I’m trying to think of how to respond when I catch a glimpse of Andrew standing just inside the glass emergency room doors. He looks awful, and he’s crying. A doctor wearing green scrubs is with him; their heads bent together, Andrew nods, a fist clutched to his mouth as the doctor talks.

Emma glances at her watch. “Meg, I need to get home. Can you stay for a bit? Andrew’s parents are on their way, but they’ve got an hour’s drive or so before they can get here.”

“Of course,” I say, my voice cracking. I clear my throat. “Thank you, Emma.” I’m not sure exactly what I’m thanking her for, but it’s the first thing that comes to mind. It’s so strange to be sitting next to her, talking with her like this after all these years of silence. I wonder if she’s feeling as discombobulated as I am.

She nods and gives me a small smile. “Will you keep me updated?”

“I will,” I say, thinking perhaps this will be the moment when I forgive Emma Steen for kissing my husband, because it suddenly feels like such a small thing in the face of this tragedy we’ve shared.

A few minutes after Emma and Charlotte leave, Andrew walks into the waiting room. He looks surprised to see me, and I quickly stand to meet him. “Emma had to go home,” I say. “But I’m happy to stay with Sam for as long as you need me to. Or he can come home with us. Whatever’s best for you.”

“They’re taking Jack into surgery,” Andrew says, and I let out a weak, “oh.” He goes to say something else, but then leans toward me and puts his forehead on my shoulder in much the same way Sam did with Audrey at the accident scene. His arms stay at his sides and we stand there for a moment in the packed waiting room, awkwardly close yet with only his forehead and my shoulder making contact, his cries muffled by my jacket.

Then I swiftly step closer and wrap my arms around him, and he does the same to me, holding tight in a way that feels too intimate yet exactly right for the moment. I feel tears prick my eyes but will myself not to cry. I take a deep breath, smell a hint of something woodsy, like aftershave or cologne, and squeeze him tighter when I exhale. His chest heaves against mine, and his heart beats furiously. A moment later he pulls away so quickly, I’m left with arms still in a semicircle, suspended in the air. I quickly drop them, feeling uncomfortable.

“Thank you,” Andrew says, scrubbing a hand across his chin and wiping at his eyes. He sounds better, stronger, though he looks anything but, and we sit back down.

“It’s the least I can do.”

He tilts his head slightly to the side, confusion on his face, and I feel self-conscious. Then he turns to Sam, who is sitting with Audrey on another bank of waiting room chairs. “How are you doing, buddy? Feeling okay?”

“I’m fine, Dad,” Sam says, only briefly raising his eyes to meet Andrew’s.

“Good,” he says. Then more quietly he says to me, “He’s been sick. Has had this fever and sore throat thing for a couple of days.”

I nod, and then there’s a lull between us. I start to get antsy; I don’t do well with silence, especially in highly emotional situations. “How long do they expect Jack to be in surgery?”

Andrew’s jaw works furiously. I know he’s holding back more tears, and I quickly regret asking the question. “They can’t know for sure, but the surgeon said to prepare for a long night.”

Without realizing I’ve done it, I press a hand tightly to my stomach as I think of Jack in the operating room all night, his parents waiting for news, hoping for the best, trying to ignore the worst.

“Are you okay?” Andrew asks, for the first time taking in my open coat, my soiled dress—the bloodstain. He shifts his body to face mine, his hands hovering slightly in front of my stained dress. “You weren’t hurt, were you?”

“No, I’m fine,” I say. “This isn’t my...” My voice trails, thankfully stopping before I finish the sentence, say the word blood. He looks ill, because even though I didn’t say it, we’re both thinking it. I use one hand to close my coat over the stain on my dress and place my other hand on his arm. This time he rests his fingers overtop of mine and squeezes slightly.

“I’m so sorry this is happening, Andrew.” My chest contracts again, the vice grip of guilt moving through me.

He nods, mouth set in a grim line. “Me, too,” he says, voice breaking. He looks down. “They also said Jack’s back is broken. Probably from when he...hit the ground.”

“Oh, Andrew.” I’m finding it hard to breathe, the fabric of my dress, the wrapped tightness of my coat suddenly too constricting.

He keeps his voice low, so Sam and Audrey don’t hear the conversation. “They said there’s a chance he might not walk again.” His eyes fill, and his voice catches. “How the hell do you tell your kid that?”

Jack Beckett is a gifted athlete, a golfer who apparently has a decent chance at playing the professional circuit if he keeps going the way he has been. He has his whole life ahead of him: college, career, a family of his own one day. He needs to walk out of here.

“I don’t know,” I say, a little breathless. My words are the truth, but they sound terribly useless in the moment. “Andrew, is there someone else I can call for you? Or can I get you something? A coffee? Something to eat?”

He shakes his head. “Don’t think I could keep anything down. Thanks, though.” His eyes drop to his phone, where a text message illuminates the screen, and he’s quickly typing back to whoever it is. I tell him I’m just stepping out to make a call, then once outside, sit on a bench beside a hospital gown–clad woman attached to an IV pole, halfway through a cigarette. I can’t catch my breath and so bend at the waist and suck in great heaving lungfuls of air.

“You okay, honey?” the woman asks, her voice raspy. She rests her elbows on her splayed knees and takes a long pull on her cigarette, watching me.

I look to her face, heavily wrinkled and a sickly shade of yellow, and shake my head. “No,” I say. The cigarette smoke is making me nauseous, and I want to leave, but my legs aren’t yet ready to hold my weight.

She nods. “Most of us here aren’t.”

6

“I want to stay with Sam,” Audrey implores, after I tell her we need to head home. Andrew’s parents and sister, Suzanne, have arrived, and Alysse managed to get on a flight that will get her here before Jack’s out of surgery.

“We should give them some privacy, Aud,” I reply quietly. I wonder when you learn that particular nuance of crisis—that giving people time and space is appropriate in situations like these—but then just as quickly wonder if that’s actually the best thing for anyone. When Audrey asks again if she can stay with Sam, this time a bit louder, I wish I could use the old “Three...two...one...” trick I used to when she was a preschooler. Audrey would usually concede when I got to “one,” and I never had to follow through on whatever consequence would happen after the countdown. But she’s a teenager now, on the cusp of being a woman who can make her own decisions, and my influence over her is diminishing. Which scares the hell out of me.

Andrew glances at us. “She’s welcome to stay, Meg,” he says. “Suzie can drive them back to our place in a bit.” Suzanne, who with her short blond bob and long limbs looks like the female version of Andrew, nods in response and rubs Sam’s back. I open my mouth to insist Audrey come with me, then see her face and Sam’s, and pause. He needs her right now.

“As long as you’re sure,” I say to Andrew. He murmurs again that it’s fine, and I nod. “Audrey, Dad or I will come get you at Sam’s place a bit later. Text me, okay?”

She hugs me and assures me she will, and after a quick goodbye to Andrew and his family, I head home.

* * *

I sit at the kitchen table in my bloodstained dress, too tired to do all the things I need to: get changed, bury the dead bird, deal with work stuff. My mind is both racing too fast and moving too slow, and I still feel like I can’t draw a full breath.

With shaking hands I pick up my phone and dial Julie, who answers on the first ring.

“Meg! Are you okay? What happened? I heard about Jack Beckett. Oh, my God. Where are you?”

I’m crying too hard to speak.

“Are you at home? Meg?”

“Yes,” I manage to say.

“I’m coming over. Give me ten minutes.”

Nine minutes later Julie lets herself in the front door, and seconds after that she’s got me in a tight hug. “Oh, Maggie. You’re okay.” Though she’s shorter than me, no one would ever call Julie petite. She’s solid and fit, yet still has a soft layer over top of her muscles. She does not subscribe to potions, surgical interventions or negative body image, saying her girls need to see the way “God made her” and understand what a real woman’s body looks like. Her halo of dark curls, that never seem to lay flat no matter what she does, tickle my face, making me sneeze.

“Sorry,” I say, sniffling, but she doesn’t let me go.

“What’s a little snot between friends?” she asks, finally pulling back and holding either side of my face in her hands. “Mags, you look like hell.”

I sniffle again, take the tissue she hands me and honk my nose into it. “I know. I feel like hell, too.”

“Why don’t you go get changed and I’ll make you a cup of tea.” She gently nudges me toward the stairs. “After that you can tell me what happened. Okay?”

I nod. “Thanks. Also, there’s a dead bird upstairs. I need to bury it before Audrey gets home.”

Julie doesn’t miss a beat. “Then I’ll meet you upstairs with tea, and rubber gloves. Off you go.”

Once I’ve stripped out of the bloodstained dress, balling it up with the pashmina and stuffing both into a plastic bag in my closet that I’ll throw in the trash bin later, I pull on some yoga pants and a sweatshirt and swallow two more ibuprofen. I’m standing at the balcony door staring at the tiny brown bird, lying exactly where it fell this morning, when Julie comes in my bedroom.

“Here,” she says, putting the hot tea in my hands. I take a tentative sip, and my eyes widen, the honey and lemon mingling with a hit of whiskey. She shrugs. “I brought the booze with me. Figured this was the time for something stronger than chamomile.” She’s wearing the pink rubber gloves I keep under the kitchen sink and has her hands on her hips. “So that’s the little guy, huh?”

I nod, staring back at the bird. In a flash I see Jack on the road, feel the pills I just swallowed trying to make their way back up.

“Do you want to talk about it?” she asks, and I know she doesn’t mean the bird.