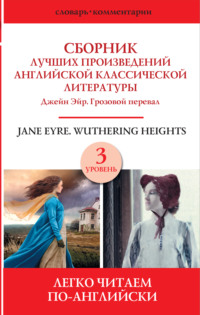

Джейн Эйр / Jane Eyre

Полная версия

Джейн Эйр / Jane Eyre

Жанр: зарубежная классикаизучение языкованглийский языклексический материалтекстовый материалзадания по английскому языкуанглийская классикаUpper-Intermediate levelзнания и навыки

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 1847

Добавлена:

Серия «Легко читаем по-английски»

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу